Disulfide Bond Formation in Secreton Component PulK Provides a Possible Explanation for the Role of DsbA in Pullulanase Secretion (original) (raw)

Abstract

When expressed in Escherichia coli, the 15 Klebsiella oxytoca pul genes that encode the so-called Pul secreton or type II secretion machinery promote pullulanase secretion and the assembly of one of the secreton components, PulG, into pili. Besides these pul genes, efficient pullulanase secretion also requires the host dsbA gene, encoding a periplasmic disulfide oxidoreductase, independently of disulfide bond formation in pullulanase itself. Two secreton components, the secretin pilot protein PulS and the minor pseudopilin PulK, were each shown to posses an intramolecular disulfide bond whose formation was catalyzed by DsbA. PulS was apparently destabilized by the absence of its disulfide bond, whereas PulK stability was not dramatically affected either by a dsbA mutation or by the removal of one of its cysteines. The pullulanase secretion defect in a dsbA mutant was rectified by overproduction of PulK, indicating reduced disulfide bond formation in PulK as the major cause of the secretion defect under the conditions tested (in which PulS is probably present in considerable excess of requirements). PulG pilus formation was independent of DsbA, probably because PulK is not needed for piliation.

Secretion of the enzyme pullulanase (PulA) by Escherichia coli K-12 expressing the Klebsiella oxytoca pul genes encoding the Pul secreton or type II secretion pathway is retarded in strains carrying a knockout mutation in the dsbA gene (28), which encodes a periplasmic disulfide bond oxidoreductase (1). Initially, we proposed that DsbA-catalyzed intramolecular disulfide bond formation in PulA was required for its recognition and secretion by the Pul secreton (28), an interpretation strengthened by the demonstrated requirement for this enzyme in other type II secretion systems (34, 39). However, removal of all possible disulfide bonds in PulA by site-directed cysteine substitutions did not block its secretion, which remained partially DsbA dependent (32). We concluded that one or more factors other than the correct folding of PulA must explain the requirement for DsbA in efficient PulA secretion. Three plausible explanations seemed worthy of investigation: (i) the absence of DsbA induces a stress response or alters a regulatory circuit (10, 38) and thereby reduces secreton function, (ii) DsbA affects a protein required for pullulanase folding or secreton function (32), and (iii) DsbA exerts a direct effect on one or more secreton components. This final explanation, which we discounted in our earlier studies (28), is investigated here.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and mutagenesis.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Vectors were pHSG575 and pHSG576 (37), pSU18 and pSU19 (2), and pBGS19 (35). pCHAP1270 carries the last 28 codons of pulJ fused to the first codons of lacZ from the vector (pSU18) DNA, followed by the complete pulK gene. pCHAP1271 is similar except that first six codons of lacZ are fused directly to codon 2 of pulK to give a lacZ′-′pulK gene fusion that is translated more efficiently than the wild-type pulK gene and whose product is slightly larger than wild-type pre-PulK due to the presence of LacZ-derived amino acids at its N-terminal end.

TABLE 1.

Strains of E. coli K-12 used

| Strain | Relevant characteristics | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| PAP105 | Δ_(lac-proAB)_ F′ lacI_q Tn_10 | Lab collection |

| PAP7460 | Δ_(lac-argF)U169 araD139 relA1 rps150 ΔmalE444 malG501_ F′ lacI_q Tn_10 | 26 |

| PAP7232 | Δ_(lac-argF)U169 araD139 relA1 rpsL150 malP::(pulS pulAB pulCO)_ F′ lacI_q Tn_10 | 27 |

| PAP7500 | As PAP7460 but malP::(pulS pulAB pulCO) | 26 |

| JCB570 | Δ_(lac-argF)U169 araD139 relA1 rpsL150 phoR zih-12_::Tn_10_ | J. Bardwell (1) |

| JCB571 | As JCB570 but dsbA::kan-1 | J. Bardwell (1) |

| PAP7246 | As PAP7232 but dsbA::kan-1 | 28 |

| PAP7498 | As PAP7460 but dsbA::kan-1 | This study |

| PAP7499 | As PAP7500 but dsbA::kan-1 | This study |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used

| Plasmid | Vector | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCHAP231 | pBR322 | pulS pulAB pulC to pulO (Apr) | 12 |

| pCHAP1219 | pBR322 | As pCHAP231 but pulS::Tn5 (Apr) | 12, 26 |

| pCHAP1325 | pBR322 | As pCHAP231 but Δ_pulK_::kan-2 (Apr) | 26 |

| pCHAP580 | pSU19 | _lacZ_p-pulS (Cmr) | 11, 26 |

| pCHAP5506 | pSU19 | As pCHAP580 but pulS codes for protein with C-terminal His8 extension | This study |

| pCHAP3094 | pSU19 | As pCHAP580 but with Cys36Ser substitution in PulS (Cys1−) (Cmr) | This study |

| pCHAP3095 | pSU19 | As pCHAP580 but with Cys90Ser substitution in PulS (Cys2−) (Cmr) | This study |

| pCHAP3093 | pSU19 | As pCHAP580 but with Cys36Ser and Cys90Ser substitutions in PulS (Cys1− Cys2−) (Cmr) | This study |

| pCHAP1371 | pHSG576 | As pCHAP580 (Cmr) | This study |

| pCHAP1377 | pHSG576 | As pCHAP3095 (Cmr) | This study |

| pCHAP1270 | pSU18 | pulK (Cmr) | 26 |

| pCHAP1271 | pSU18 | (lacZ′-′pulK) (Cmr) | 26 |

| pCHAP3129 | pSU18 | As pCHAP1270 but with Cys96Ser substitution in PulK (Cmr) | This study |

| pCHAP1374 | pHSG575 | As pCHAP1270 (Cmr) | This study |

| pCHAP1375 | pHSG575 | As pCHAP3129 (Cmr) | This study |

| pCHAP4260a | pUC18 | _lacZ_p-(pelB′-′pulA) (Apr) | O. Francetic |

| pCHAP1367 | pUC18 | As pCHAP4260 but with pulK gene from pCHAP1270 cloned behind (pelB′-′pulA) (Apr) | This study |

| pCHAP1368 | pUC18 | As pCHAP4260 but with pulS gene from pCHAP580 cloned behind (pelB′-′pulA) (Apr) | This study |

| pCHAP163 | pHSG576 | lacZp-pulG | 27 |

| pCHAP3100 | pSU18 | _lacZ_p-ppdD (Cmr) | 31 |

| pCHAP576 | pBGS19 | lacZp-pulO | 26 |

| pCHAP710 | pACYC184 | pulS, pulC to pulO (Cmr) | 17 |

The gene coding for the His-tagged PulS protein carried by pCHAP5506 (Table 2) was obtained by PCR amplification of pulS using a 5′ primer that included the _Eco_RI cloning site in its 5′ upstream region and a 3′ primer than included eight His codons before the stop codon and a _Hin_dIII site.

Linkers were inserted either side of the pulK and pulS genes in pCHAP580 and pCHAP1270 so that they could be cloned into the _Hin_dIII site immediately 3′ to pulA in pCHAP4260 to give pCHAP1367 and pCHAP1368, in which pulK and pulS are in the same orientation as pulA and are expressed from the lacZ promoter in the vector (pUC18). The pulS gene is also expressed from its own promoter in all of the constructs used.

Site-directed mutagenesis (19) was used to convert Cys codons in fragments of pulS and pulK cloned in M13 phage mp18. The entire mutagenized fragment was sequenced to confirm the absence of other changes and then was used to replace the corresponding wild-type fragment in pCHAP580 and pCHAP1270, respectively.

Analytical procedures.

In most experiments, bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (22) at 30°C. Induced expression of pulA and the pulC to pulO operon from pulAp and pulCp was achieved by adding 0.4% maltose to medium buffered to pH 7.2 with 10 mM phosphate. Expression of genes under lacZp control was achieved by adding 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG). Antibiotics were used as follows: ampicillin, 200 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; and chloramphenicol, 20 μg/ml.

The enzymatic assay for pullulanase secretion was used previously (21, 32). Secretion levels are indicated as the proportion of the total amount of pullulanase activity present in detergent-lysed cells that could be measured in unlysed cells. Each assay was performed separately at least three times. Values of 0 to 20% are considered negative, values of 20 to 80% are considered intermediate, and values of 80 to 100% are considered positive. To assay secretion of soluble pullulanase encoded by pCHAP4260, cells were separated from medium and resuspended in sample buffer for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The spent medium was diluted in 2× sample buffer, and material from equal amounts of cell suspension and medium were separated by SDS-PAGE for immunodetection of pullulanase (see below). The shearing assay was performed on plate-grown bacteria as previously (33).

Membrane fractionation was performed as described previously by floating membranes prepared from cells broken in a French press through centrifuged sucrose gradients (26). SDS-PAGE was performed using Tris-glycine buffers (30). Immunoblotting was performed as described previously (26) using antiserum or purified antibodies at the following dilutions: PulA, 1:10,000; PulG, 1:5,000; MalE-PpdD, 1:5,000; MalE-PulS, 1:10,000; PulD, 1:200; MalE-PulC, 1:1,000; MalE-PulM, 1:2,000; MalE-PulE, 1:1,000; MalE-PulL, 1:1,000; MalE-PulK, 1:5,000; and SecG, 1:5,000.

PulS-His8 produced by cultures of PAP105(pCHAP5506) was purified from outer membranes solubilized in the zwitterionic detergent 3-(_N,N_-dimethylmyristylammonio)proprionosulfonate (SB3-14) as described previously for PulS complexed to PulD (23). The soluble extract was bound to a Talon cobalt affinity column (Clonetech), washed extensively with the loading buffer containing 50 mM imidazole, and then eluted with 50 mM EDTA. The eluate was then loaded on a Sephacryl S300HR column and eluted with the same detergent buffer (23). The purified protein was then reduced by treatment with 5 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl)phosphene hydrochoride (TCEP) by heating to 100°C for 3 min. After 1 h at room temperature, 50 μg of fluorescein 5-maleimide per ml was added and incubation was continued for 1 h. Proteins were then precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid, dissolved in SDS-PAGE sample buffer without reductant, and loaded onto a 12% acrylamide gel.

Pulse-labeling was performed on bacteria grown at 30°C in M63 minimal medium containing 0.4% glycerol. 14C-amino acids (CEA, Saclay, France) (50 μCi · ml−1) were added to aliquots of the culture, and incubation was continued for 3 min. At the start of the chase period, 0.1% Casamino Acids and 100 μg of spectinomycin per ml were added, and incubation was continued. Samples withdrawn at the indicated times thereafter were mixed with trichloracetic acid (6%) to precipitate proteins. The pellet was resuspended in 25 mM Tris buffer (pH. 8.0) containing 1% SDS and 1 mM EDTA, heated to 100°C for 5 min, and diluted 10-fold in 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0) containing 0.15 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 2% Triton X-100 (final volume, 500 μl). After removal of insoluble material by centrifugation, 200 μl was incubated overnight with 1 μl of anti-MalE-PulS at 4°C. Immunoglobulins and bound proteins were then collected on protein A-Sepharose beads (Amersham-Pharmacia). The beads were resuspended in sample buffer, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. The gels were fixed in 50% ethanol containing 10% acetic acid and then soaked in Amplify (Amersham-Pharmacia) before being exposed to Kodak X-AR film.

RESULTS

PulS has an intramolecular disulfide bond.

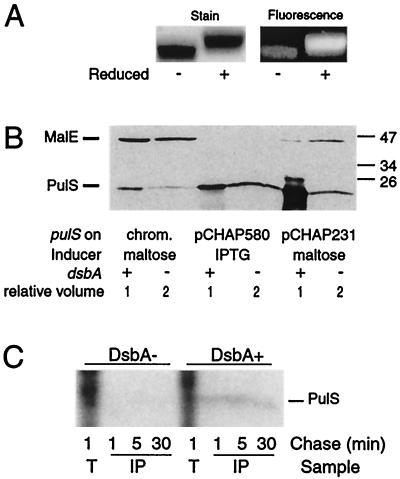

Only 2 of the 12 Pul secreton components required for secretion (26), PulS (11) and PulK (29), have more than one cysteine and the correct predicted membrane topology for intramolecular disulfide bond formation in the periplasm. PulS, a lipoprotein component of the outer membrane secretin complex (23), acts as a pilot to guide secretin PulD to the outer membrane (8, 13, 15). In E. coli K-12 expressing the entire pul gene cluster cloned in pBR322 (pCHAP231), PulS is associated exclusively with the outer membrane (Fig. 1), while PhoA fusions to PulS have alkaline phosphatase activity (11), implying that they are exposed to the periplasm. First, we tested whether PulS has an intramolecular disulfide bond. For this purpose, a purified His-tagged variant of PulS (PulS-His8, encoded by pCHAP5506) was labeled with the cysteine-specific fluorescein 5-maleimide in the presence or absence of the reducing agent TCEP. Comparison of the migrations of the reduced and nonreduced forms on SDS-PAGE and the considerably higher level of labeling achieved with the TCEP-treated form of the protein indicated the existence of an intramolecular disulfide bond (Fig. 2A).

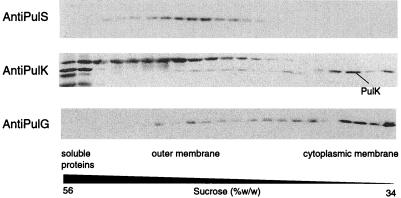

FIG. 1.

Localization of PulS, PulK, and PulG proteins by flotation sucrose gradient centrifugation of membranes from E. coli K-12 PAP7460(pCHAP231) grown in medium containing 0.4% maltose. Fractions collected from the gradients were examined by SDS-PAGE (11.3% acrylamide, 8 M urea) and immunoblotting with the appropriate antibodies. Only those regions of the immunoblots displaying the relevant proteins are shown. The PulK antibodies also reacted with two soluble proteins that remained at the bottom of the gradient and with an outer membrane protein (probably OmpA), which serve as markers. Cytoplasmic and outer membrane proteins were visualized by protein staining, and cytoplasmic membrane protein SecG was detected by immunoblotting. The bands designated PulS, PulK, and PulG were not detected in membranes from strains carrying pCHAP1219 (pCHAP231 pulS), pCHAP1323 (pCHAP231 pulK), and pCHAP1216 (pCHAP231 pulG) (26).

FIG. 2.

Evidence that PulS contains a DsbA-catalyzed intramolecular disulfide bond (A) Effect of reduction of purified PulS-His8 on its migration and on the accessibility of cysteine residues to fluorescein 5-maleimide. The labeled protein was separated on a 12% acrylamide gel and either stained with Coomassie blue (left panel) or photographed under UV light (right panel). (B) Examination of PulS protein encoded in wild-type and DsbA− strains of E. coli K-12 carrying two different plasmids (pCHAP580 and pCHAP231) (strains JCB570 and JCB571, respectively) or with pulS in the chromosomal gene cluster (strains PAP7232 and PAP7246, respectively). Proteins were separated on an 11% acrylamide gel and immunoblotted with antibodies against a MalE-PulS hybrid protein. Note that twice as much material was loaded from the DsbA− mutants as from the wild-type strain. MalE protein encoded by the chromosomal malE gene in strains induced with maltose (pCHAP231 and chromosomal pul genes) serves as an internal control. (C) Stability of PulS encoded by pCHAP580 in strains PAP7498 (dsbA) and PAP7460 (wild type), as determined by pulse-labeling with 14C-amino acids and a chase with unlabeled Casamino Acids. Samples of total labeled cells at 1 min after addition of chase (T) and proteins immunoprecipitated with antibodies against MalE-PulS (IP) after 1, 5, and 30 min of chase were separated on an 11.3% acrylamide–8 M urea SDS-polyacrylamide gel and detected by fluorography. The positions of prestained molecular size markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated in panel B.

DsbA might be expected to catalyze the formation of this disulfide bond in PulS. This possibility was tested by immunoblot analyses, which revealed that a dsbA mutation diminished the amount of PulS detectable in strains with the pul gene cluster in the chromosome or on pBR322 (pCHAP231) or with pulS cloned under lacZp control (pCHAP580) (Fig. 2B).

From these experiments, we concluded that the failure to detect PulS in DsbA−, mutants could be due to its degradation. Therefore, we performed pulse-chase experiments with 14C-amino acid-labeled PulS. In wild-type bacteria carrying pCHAP580 and expressing pulS alone under lacZp control, PulS was stable over a 30-min period, whereas it was not detectable in a DsbA− mutant carrying this plasmid (Fig. 2C). Therefore, DsbA apparently catalyzes the formation of the disulfide bond that stabilizes PulS and prevents its proteolysis. The trace amounts of PulS detected by immunoblotting in DsbA− mutants probably correspond to protein in which an intramolecular disulfide bond has formed despite the absence of DsbA.

PulK has an intramolecular disulfide bond.

The pulK gene is located immediately downstream from four genes in the _pulC_-to-pulO operon (pulG, pulH, pulI and pulJ) that encode so-called pseudopilins, type IV pilin-like proteins of which three are needed for pullulanase secretion (27, 29, 33). Like the pseudopilins, PulK has a highly hydrophobic N-terminal region that resembles those of type IV pilins (27, 29, 36). However, we originally considered PulK not to be a pseudopilin because it lacks the highly conserved glutamate residue at position +4 (29) near the consensus cleavage site (27) for prepilin peptidase, which processes both type IV pilins and pseudopilins. The only homologue of PulK that has been examined in any detail is XcpX from the Xcp secreton of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. A hybrid protein formed by fusing the N-terminal region of XcpX to PhoA was processed by prepilin peptidase (PilD/XcpA) (3).

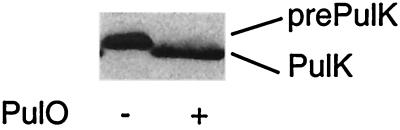

To study pre-PulK processing, we used a lacZ_′-′_pulK gene fusion under lacZp control on a multiple-copy-number plasmid (pCHAP1271; see Materials and methods). This lacZ_′-′_pulK gene fusion complements a pulK mutation (26), indicating that it encodes a functional protein. Compared to native PulK, the LacZ-PulK hybrid has five additional amino acids derived from vector-encoded LacZ at its N-terminal end, making it easier to distinguish between the precursor and mature forms of the protein because 12, rather than 7, amino acids should be removed during processing. The data in Fig. 3 show that LacZ-PulK was processed by prepilin peptidase (PulO), despite the absence of the highly conserved glutamate residue at position +4 (29) of the consensus cleavage site (27). Therefore, like XcpX, PulK is an authentic pseudopilin

FIG. 3.

Processing of LacZ-PulK protein by PulO. Extracts of cells from IPTG-induced cultures of strain PAP7460 carrying pCHAP1271 (lacZ′-′pulK) with or without pCHAP576 (lacZp-pulO) were separated by SDS-PAGE on an 11.3% acrylamide–8 M urea gel and then immunoblotted with antibodies against MalE-PulK. Only that portion of the immunoblot displaying precursor (prePulK) and mature (PulK) forms of LacZ-PulK is shown.

Examination of membranes prepared from strains carrying all of the pul secreton genes on a multiple-copy plasmid (pCHAP231) by sucrose gradient flotation revealed that PulK was located mainly in the cytoplasmic membrane (Fig. 1) together with the cytoplasmic membrane marker protein SecG (not shown) and pseudopilin PulG (Fig. 1). Since PulK-PhoA hybrid proteins have alkaline phosphatase activity (29), we assume that PulK is anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane and faces the periplasm. PulK does not appear to be present in the surface-anchored secreton pili, whose formation is independent of this protein (33).

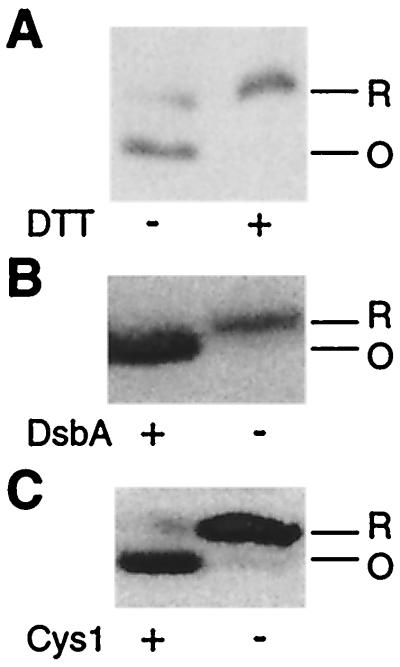

PulK has two cysteine residues (other pseudopilins have none). It is a very minor protein that cannot be detected by immunoblotting of whole-cell extracts of strains with the pul gene cluster in the chromosome or on the multiple-copy-number plasmid pCHAP231, because comigrating proteins are also recognized by affinity-purified MalE-PulK antibodies. Therefore, we used strains carrying multiple-copy-number plasmids carrying a lacZp-pulK operon fusion (pCHAP1270) or the lacZ′-′pulK gene fusion (pCHAP1271), which produce more PulK, to determine whether PulK has a DsbA-catalyzed disulfide bond. Treatment of cell extracts with dithiothreitol (Fig. 4A) or production of PulK in a DsbA− mutant (Fig. 4B) caused a change in the migration of PulK upon SDS-PAGE, consistent with the presence of a disulfide bond.

FIG. 4.

Evidence that PulK contains a DsbA-catalyzed intramolecular disulfide bond. (A) Effect of dithiothreitol (DTT) (10 mM) on migration of pCHAP1271-encoded LacZ′-′PulK hybrid protein in an 11.3% acrylamide–8M urea SDS-polyacrylamide gel. (B) Immunodetection of PulK in strains PAP7460 (DsbA+) and PAP7498 (DsbA−) carrying pCHAP1270 (lacZp-pulK). Proteins were separated in a 10% acrylamide gel. (C) Comparison of electrophoretic mobilities of PulK with (pCHAP1270) and without (pCHAP1329) Cys1 in a 10% acrylamide gel. All cultures were grown in the presence of IPTG to induce pulK. Immunoblotting with anti-MalE-PulK was performed as described for Fig. 3. Only those parts of the immunoblots displaying PulK are shown. R, reduced; O, oxidized.

PulS derivatives lacking their disulfide bond.

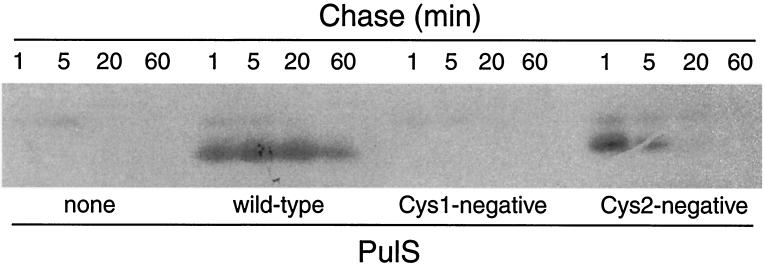

If the absence of DsbA-catalyzed disulfide bond formation in PulS explains the pullulanase secretion defect in DsbA− mutants, complete abolition of disulfide bond formation by removing one or both of the cysteines should have an even more dramatic effect. PulS has three cysteine residues, of which the first, the N-terminal residue of mature PulS, is fatty acylated (11) and is needed for its function (15). For convenience, the other two cysteines are referred to as Cys1 (position 36 of lipoprotein signal peptidase-processed PulS) and Cys2 (position 90). PulS encoded by multiple-copy-number plasmids with the Cys1, Cys2, or Cys1-Cys2 codons in pulS changed to Ser was undetectable by immunoblotting except with heavily loaded samples, when the protein lacking Cys2 could be detected in trace amounts (not shown). In pulse-chase experiments, the PulS Cys1− variant was undetectable, whereas the Cys2− derivative remained detectable only for a short time after labeling (Fig. 5). Therefore, the absence of a disulfide bond in PulS destabilizes the protein, as observed in the DsbA− mutant.

FIG. 5.

Effect of cysteine substitutions on immunodetection and stability of PulS determined by pulse-chase analysis of PulS variants produced by strain PAP7460 carrying pCHAP580 or its derivatives with Cys1 or Cys2 substitutions. The control plasmid (none) was the empty vector (pSU19). Proteins were labeled with 14C-amino acids and immunoprecipitated with antibodies against MalE-PulS after the indicated times of chase with unlabeled Casamino Acids.

The multiple-copy-number plasmids encoding the Cys1− or the Cys1−-Cys2− derivatives of PulS were unable to complement the pulS::Tn_5_ mutation carried by a plasmids with the entire pul gene cluster except pulS (pCHAP1219) (Table 3), as expected from the absence of detectable protein. However, the Cys2− variant of PulS was almost fully functional in this assay (Table 3). Strains carrying wild-type pulS in the same vector (pCHAP580) produce a considerable molar excess of PulS over PulD encoded by pCHAP1219. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that the short-lived PulS Cys2− variant produced in these experiments is sufficient to guide PulD to the outer membrane and to allow it to become functional. To test this possibility, wild-type pulS and the pulS gene coding for PulS Cys2− were subcloned into the low-copy-number plasmid vector pHSG576 (pCHAP1371 and pCHAP1377, respectively). When these plasmids were used in the complementation assay, wild-type pulS functioned normally but the gene coding the Cys2− derivative was totally defective (Table 3). Therefore, we conclude that the two cysteines in PulS are required for its stability and that high-level production of a short-lived variant of PulS incapable of forming an intramolecular disulfide bond (PulS Cys2−) can overcome the pullulanase defect caused by the complete absence of PulS.

TABLE 3.

Complementation of pulS::Tn_5_ carried by pCHAP1219 by pulS alleles carried by compatible plasmidsa

| Complementing plasmid | pulS mutation | IPTG induction | Pullulanase secretion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCHAP580 | − | 80–100 | |

| pCHAP1371 | − | 80–100 | |

| pCHAP3094 | Cys1− | + | 0–10 |

| pCHAP3095 | Cys2− | − | 40–70 |

| + | 80–100 | ||

| pCHAP1377 | Cys2− | − | 0–10 |

| + | 10–20 | ||

| pCHAP3093 | Cys1− Cys2− | + | 0–10 |

A PulK derivative lacking its disulfide bond.

The two cysteine residues in PulK are located at positions 96 (Cys1) and 200 (Cys2) of the processed polypeptide (29). PulK in which Cys1 was replaced by Ser migrated more slowly than unaltered PulK due to the loss of the intramolecular disulfide bond (Fig. 4C). Nevertheless, a multiple-copy-number plasmid expressing the mutant pulK allele under lacZp control (pCHAP3129) was able to restore secretion in a strain carrying the entire pul gene cluster except pulK on a compatible multiple-copy-number plasmid (pCHAP1325) (Table 4). However, when the gene was expressed from the same promoter of a low-copy-number plasmid (pCHAP1375), it was able to complement the ΔpulK mutation only when IPTG was added to the growth medium to induce pulK expression, and even then, complementation was incomplete (Table 4). In contrast, the wild-type allele of pulK was fully functional under all of these conditions (pCHAP1374) (Table 4). Thus, as with PulS, the disulfide bond in PulK appears necessary for optimal function in genetic complementation tests, but overproduction of PulK that is unable to form a disulfide bond still restores secretion in a PulK− mutant.

TABLE 4.

Complementation of pulK mutation carried by pCHAP1325 by pulK alleles carried by compatible plasmidsa

| Complementing plasmid | pulK mutation | IPTG induction | Pullulanase secretion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| pCHAP1270 | − | 80–100 | |

| pCHAP1374 | − | 80–100 | |

| pCHAP1271 | lacZ′-′pulK | − | 80–100 |

| pCHAP3129 | Cys1− | − | 80–100 |

| pCHAP1375 | Cys1− | − | 0–10 |

| + | 30–40 |

Complementation of dsbA mutation by high-level expression of pulS or pulK.

The observations reported above suggested that the defect in pullulanase secretion observed in mutants lacking DsbA might be explained by reduced oxidation (or reduced levels) of PulS, PulK, or both. If this is the case, then the defect should be overcome by increasing the levels of one or both proteins.

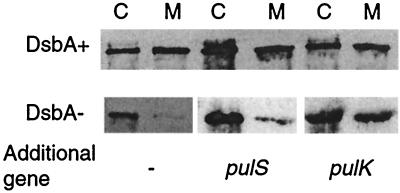

Secretion was analyzed in a strain carrying a plasmid that carries all pul genes except pulA (pCHAP710) (17) and a high-copy-number plasmid carrying a pelB′-′pulA gene fusion encoding a nonacylated form of pullulanase (pCHAP4260) (O. Francetic, unpublished data). This protein is similar to the product of the malE′-′pulA gene fusion used previously (25, 32) but is secreted more efficiently and is more stable. The use of this system allows secretion levels to be determined more easily than with the protease accessibility assay originally used (28). In the wild-type strain, approximately half of the PulA was extracellular (25, 32), but the level of secretion was considerably lower in the DsbA− mutant (Fig. 6). This secretion defect was not abolished when pulS was cloned behind pelB′-′pulA to make an artificial (pelB′-′pulA)-pulS operon (pCHAP1368) (Fig. 6). In contrast, expression of pulK from the same plasmid as pelB′-′pulA restored secretion in the DsbA− mutant to wild-type levels (pCHAP1367) (Fig. 6). Therefore, we conclude that the reduced level of pullulanase secretion caused by the absence of DsbA (28, 32) is due to the effect of the dsbA mutation on PulK. The constitutively high level of PulS production in strains carrying multiple-copy-number plasmids with the entire pul gene cluster would mask any effect of DsbA on this protein.

FIG. 6.

Restoration of pullulanase secretion in DsbA− strain PAP7498 by overproduction of PulK. Cells (lanes C) of PAP7460 (DsbA+) and PAP7498 carrying pCHAP710 and pCHAP4260 (lacZp-pulA) or its derivative with genes pulS (pCHAP1368) or pulK (pCHAP1367) cloned behind pulA were grown in medium containing maltose and IPTG and then centrifuged to separate than from the medium (lanes M). The 9% acrylamide gel was loaded with equal amounts (5-μl equivalent of initial culture) of the two samples. Pullulanase was detected by immunoblotting with PulA antiserum.

We previously reported that E. coli K-12 strains carrying a chromosomal pul locus (e.g., strain PAP7500) exhibited slightly lower levels of PulA secretion if they also carried a dsbA mutation (e.g., strain PAP7499) (28). This secretion defect could not be corrected by overexpression of either pulS or pulK (not shown). Strains overexpressing both genes simultaneously could not be analyzed because they lysed when harvested.

Other effects of DsbA on Pul proteins.

We also used immunoblotting to study the effects of the absence of DsbA on other Pul proteins in a strain with the pul gene cluster integrated into the chromosome. The levels of PulC, PulE, PulG, PulL, and PulM in strain PAP7499 (dsbA) were the same as those in the parent strain PAP7500. However, the level of PulD in the former was reduced to approximately half (not shown), probably as a result of the reduced levels of its pilot protein PulS (13).

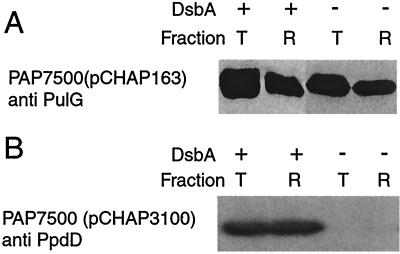

DsbA is not needed for secreton pilus formation but stabilizes type IV pilin PpdD.

Recently, we reported that the major pseudopilin encoded by secreton gene pulG can be assembled into pili when bacteria are grown on plates (33). One of the two identified targets for DsbA, PulK, is not needed for the formation of these pili, whereas PulS is required for piliation (33). PulG is assembled into pili in bacteria carrying the pul genes in the chromosome provided that the bacteria also carry pulG on a low-copy-number plasmid such as pCHAP163 (Fig. 7). According to the release of surface proteins by shearing, PulG pilus production under these conditions was not diminished by the absence of DsbA (Fig. 7), suggesting that there is sufficient oxidized PulS present in these bacteria to allow pilus assembly (as well as pullulanase sectretion).

FIG. 7.

DsbA is not needed for secreton pilus formation but is needed for production of type IV pilin PpdD in strains with the pul genes integrated into the chromosome. (A) Immunodetection of PulG in total cell extracts (lanes T) and in material released by shearing (lanes R) from plate-grown cultures of strain PAP7500(pCHAP163) or its DsbA− derivative PAP7498(pCHAP163). Proteins were separated on an 11.3% acrylamide–8 M urea gel and immunoblotted with antibodies against PulG. (B) Immunodetection of PpdD in plate-grown cultures of strain PAP7500(pCHAP3100) and its DsbA− derivative PAP7499(pCHAP3100). Samples were treated as described for panel A, and PpdD was immunodetected with antibodies against MalE-PpdD.

PulG does not have a disulfide bond, but type IV pilins do contain a disulfide bond whose formation is catalyzed by DsbA (40). The E. coli type IV pilin PpdD, which has an intramolecular disulfide bond (31), can be assembled by the secreton (33). In strains with the pul genes in the chromosome and ppdD on a high-copy-number plasmid (pCHAP3100) (31), the absence of DsbA dramatically reduced the amount of PpdD detected (Fig. 7). Thus, disulfide bond formation in PpdD pilin is apparently required for its stability, whereas pseudopilin PulK appears to be stable and even partially functional without its disulfide bond.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we report that a dsbA mutation causes failure to form intramolecular disulfide bonds in PulK and PulS. PulK without a disulfide bond appears to be stable, but PulS without a disulfide bond is apparently rapidly degraded. Therefore, secretion defects resulting from failure to form disulfide bonds in these proteins might be explained by a lower ability of the protein to function in secretion (PulK) or by the presence of smaller amounts of protein (PulS). The previously reported pullulanase secretion defect in DsbA− strains carrying all of the pul genes on pBR322 (pCHAP231) was probably entirely due to suboptimal PulK activity, because we show here that pCHAP231 encodes sufficient PulS to overcome any deleterious effects of the dsbA mutation on this protein. This conclusion is similar to that derived from studies on the effects of dsb mutations of flagellar assembly (9).

In other type II secretion systems, the major secretion defect in DsbA− mutants arises through destabilization of secreted proteins caused by their lack of an intramolecular disulfide bond (4, 34, 39). These dramatic effects, which are not observed in the pullulanase secretion pathway, would mask any other effects of the dsbA mutation such as those reported here. Indeed, the effect of dsbA mutations on pullulanase secretion is similar in many respects to the recently reported effects of such mutations on cellulase CelV secretion in Erwinia carotovora (38). CelV does not have cysteines and, therefore, is not directly affected by DsbA. Nevertheless, DsbA− mutants secreted CelV less efficiently than wild-type bacteria. This partial secretion defect was attributed to the higher level of CelV production observed in the DsbA− mutant (38). In the light of our results, the possibility that the defect was due to reduced activity of the PulK homologue OutK (20) or of the PulS homologue OutS should also be considered. Similar, subtle effects of dsbA mutations might be uncovered in other bacteria such as Aeromonas hydrophila, which use the secreton to secrete proteins that lack intramolecular disulfide bonds (6, 14). One possible exception might be P. aeruginosa, in which DsbA is required for type II secretion and stability of secreted proteins with disulfide bonds (K.-E. Jaeger, personal communication) but in which the PulK homologue (XcpX) has only one cysteine (3) and a PulS homologue has not been identified.

A potentially interesting observation reported here is that, under certain circumstances, the dramatically reduced stability of PulS caused by the absence of DsbA did not appear to affect the ability of the Pul secreton to function normally. PulS was originally described as a chaperone that directs secretin PulD to the outer membrane and protects it from proteolysis (13, 15) by binding to its C-terminal end (8). Subsequently, we showed that PulD and PulS form a stable complex (23, 24). Therefore, the term chaperone was considered inappropriate to describe PulS (23). However, both the highly unstable PulS produced in a DsbA− mutant and an equally unstable PulS variant lacking one of the cysteines that are involved in intramolecular disulfide bond formation function normally when they are overproduced. Sufficient disulfide-bonded PulS might be formed in the absence of DsbA to ensure correct localization and assembly of secretin PulD, but the Cys2− variant of PulS, which is at least partially functional, is unable to form an intramolecular disulfide bond. Thus, the short-lived Cys2− variant or the short-lived PulS produced by DsbA− strains might survive long enough to pilot PulD to the outer membrane before it is degraded. If this is the case, the secretin complex purified from the outer membranes of these strains should not have PulS associated with it. It is interesting that secretins purified from other bacteria are not associated with their pilot proteins (5, 7), possible because they do not remain attached to secretin or are degraded. It is also interesting that the secretin from the type III secretion pathway in Yersinia pestis is destabilized by a dsbA mutation despite the fact that it lacks cysteines (16), an effect that might be attributable to failure to form disulfide bonds in a protein that is functionally similar to PulS (18).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all members of the secretion and maltose labs for their constant interest and support, and especially Nathalie Nadeau for technical assistance, Olivera Francetic for pCHAP4260, Ingrid Guilvout and Nico Nouwen for information on the relative levels of PulS and PulD, and Frank Ebel for antibodies against MalE-PulK. We are also grateful to Bill Wickner for antibodies to SecG protein and to Karl-Erich Jaeger and Alain Filloux for information prior to publication.

This work was financed by the European Union (Training and Mobility grants FMRX-CT96-0004 and HPRN-CT-2000-00075), by Avantis-Pasteur, and by a French Research Ministry grant (Programme fondamental en Microbiologie et Maladies infectieuses et parasitaires).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bardwell J C A, McGovern K, Beckwith J. Identification of a protein required for disulfide bond formation in vivo. Cell. 1991;65:581–589. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90532-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartolomé B, Jubete Y, Martinez E, de la Cruz F. Construction and properties of a family of pACYC184-derved cloning vectors compatible with pBR322 and its derivatives. Gene. 1991;102:75–78. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90541-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bleves S, Lazdunski A, Tommassen J, Filloux A. The secretion apparatus of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of a fifth pseudopilin, XcpX. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:31–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bortoli-German I, Brun E, Py B, Chippaux M, Barras F. Periplasmic disulphide bond formation is essential for cellulase secretion by the plant pathogen Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:545–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brok R, Van Gelder P, Winterhalter M, Ziese U, Koster A J, de Cock H, Koster M, Tommassen J, Bitter W. The C-terminal domain of the Pseudomonas secretin XcpQ forms oligomeric rings with pore activity. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1169–1179. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brumlik M J, van der Goot F G, Wong K R, Buckley T J. The disulfide bond in the Aeromonas hydrophila lipase/acyltransferase stabilizes the structure but is not required for secretion or activity. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3116–3121. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.10.3116-3121.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crago A M, Koronakis V. Salmonella InvG forms a ring-like multimer that requires the InvH lipoprotein for outer membrane localization. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:47–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daefler S, Guilvout I, Hardie K R, Pugsley A P, Russel M. The C-terminal domain of the secretin PulD contains the binding site for its cognate chaperone, PulS, and confers PulS dependence on pIVf1 function. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:465–475. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3531727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dailey F, Berg H. Mutants in disulfide bond formation that disrupt flagellar assembly in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1043–1047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danese P N, Silhavy T J. The sigma E and the Cpx signal transduction systems control the synthesis of periplasmic protein-folding enzymes in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1183–1193. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.9.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.d'Enfert C, Pugsley A P. Klebsiella pneumoniae pulS gene encodes an outer membrane lipoprotein required for pullulanase secretion. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3673–3679. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3673-3679.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.d'Enfert C, Ryter A, Pugsley A P. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of the Klebsiella pneumoniae genes for production, surface localization and secretion of the lipoprotein pullulanase. EMBO J. 1987;6:3531–3538. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardie K R, Lory S, Pugsley A P. Insertion of an outer membrane protein in Escherichia coli requires a chaperone-like protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:978–988. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardie K R, Schulze A, Parker M W, Buckley J T. Vibrio spp. secrete proaerolysin as a folded dimer without the need for disulphide bond formation. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:1035–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17061035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardie K R, Seydel A, Guilvout I, Pugsley A P. The secretin-specific, chaperone-like protein of the general secretory pathway: separation of proteolytic protection and piloting functions. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:967–976. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson M W, Plano G V. DsbA is required for stable expression of outer membrane protein YscC and for efficient Yop secretion in Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5126–5130. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.5126-5130.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kornacker M G, Pugsley A P. Molecular characterization of pulA and its product, pullulanase, a secreted enzyme of Klebsiella pneumoniae UNF5023. Mol Microbiol. 1989;4:73–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koster M, Bitter W, de Cock H, Allaoui A, Cornelis G, Tommassen J. The outer membrane component, YscC, of the Yop secretion machinery of Yersinia enterocolitica forms a ring-shaped multimeric complex. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:789–797. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6141981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindeberg M, Salmond G P C, Collmer A. Complementation of deletion mutations in a cloned functional cluster of Erwinia chrysanthemi out genes with Erwinia carotovora out homologs reveals OutC and OutD as candidate gatekeepers of species-specific secretion of proteins via the type II pathway. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:175–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michaelis S, Chapon C, d'Enfert C, Pugsley A P, Schwartz M. Characterization and expression of the structural gene for pullulanase, a maltose-inducible secreted protein of Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:633–638. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.633-638.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller J H. A short course in bacterial genetics. A laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nouwen N, Ranson N, Saibil H, Wolpensinger B, Engel A, Ghazi A, Pugsley A P. Secretin PulD: association with pilot protein PulS, structure and ion-conducting channel formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8173–8177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nouwen N, Stahlberg H, Pugsley A P, Engel A. Domain structure of secretin PulD revealed by limited proteolysis and electron microscopy. EMBO J. 2000;19:2229–2236. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poquet I, Faucher D, Pugsley A P. Stable periplasmic secretion intermediate in the general secretory pathway of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1993;12:271–278. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Possot O, Vignon G, Bomchil N, Ebel F, Pugsley A P. Multiple interactions between pullulanase secreton components involved in stabilization and cytoplasmic membrane association of PulE. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2142–2152. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.8.2142-2152.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pugsley A P. Processing and methylation of PulG, a pilin-like component of the general secretory pathway of Klebsiella oxytoca. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:295–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pugsley A P. Translocation of a folded protein across the outer membrane via the general secretory pathway in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:12058–12062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reyss I, Pugsley A P. Five additional genes in the pulC-O operon of the Gram-negative bacterium Klebsiella oxytoca UNF5023 that are required for pullulanase secretion. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;222:176–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00633815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor. N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sauvonnet N, Gounon P, Pugsley A P. PpdD type IV pilin of Escherichia coli K-12 can be assembled into pili in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:848–854. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.848-854.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sauvonnet N, Pugsley A P. The requirement for DsbA in pullulanase secretion is independent of disulphide bond formation in the enzyme. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:661–667. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauvonnet N, Vignon G, Pugsley A P, Gounon P. Pilus formation and protein secretion by the same machinery in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2000;19:2221–2228. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shevchik V E, Bortoli-German I, Robert-Baudouy J, Robinet S, Barras F, Condemine G. Differential effect of dsbA and dsbC mutations on extracellular enzyme secretion in Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:745–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spratt B G, Hedge P J, te Heesen S, Edelman A, Broome-Smith J K. Kanamycin-resistant vectors that are analogues of plasmids pUC8, pUC9, pEMBL8 and pEMBL9. Gene. 1986;41:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strom M S, Lory S. Structure-function and biogenesis of the type IV pili. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1993;47:565–596. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takeshita S, Sato M, Toba M, Masahashi W, Hashimoto-Goto T. High copy number and low copy number plasmid vectors for lacZ α-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene. 1987;61:63–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90365-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vincent-Sealy L V, Thomas J D, Commander P, Salmond G P C. Erwinia carotovora DsbA mutants: evidence for a periplasmic-stress signal transduction system affecting transcription of genes encoding secreted proteins. Microbiology. 1999;145:1945–1958. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-8-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu J, Webb H, Hirst T R. A homologue of the Escherichia coli DsbA protein involved in disulphide bond formation is required for exotoxin biogenesis in Vibrio cholerae. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2284–2288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H-Z, Donnenberg M S. DsbA is required for stability of the type IV pilin of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:787–797. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.431403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]