Multipotent Stem Cells from the Mouse Basal Forebrain Contribute GABAergic Neurons and Oligodendrocytes to the Cerebral Cortex during Embryogenesis (original) (raw)

Abstract

During CNS development, cell migrations play an important role, adding to the cellular complexity of different regions. Earlier studies have shown a robust migration of cells from basal forebrain into the overlying dorsal forebrain during the embryonic period. These immigrant cells include GABAergic neurons that populate the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. In this study we have examined the fate of other basal forebrain cells that migrate into the dorsal forebrain, identifying basal cells using an antibody that recognizes both early (_dlx_1/2) and late (dlx 5/6) members of the dlx homeobox gene family. We found that a subpopulation of cortical and hippocampal oligodendrocytes are also ventral-derived. We traced the origin of these cells to basal multipotent stem cells capable of generating both GABAergic neurons and oligodendrocytes. A clonal analysis showed that basal forebrain stem cells produce significantly more GABAergic neurons than dorsal forebrain stem cells from the same embryonic age. Moreover, stem cell clones from basal forebrain are significantly more likely to contain both GABAergic neurons and oligodendrocytes than those from dorsal. This indicates that forebrain stem cells are regionally specified. Whereas dlx expression was not detected within basal stem cells growing in culture, these cells produced dlx-positive products that are capable of migration. These data indicate that the developing cerebral cortex incorporates both neuronal and glial products of basal forebrain and suggest that these immigrant cells arise from a common progenitor, a dlx-negative basal forebrain stem cell.

Keywords: CNS stem cells, oligodendrocytes, GABAergic neurons, telencephalon, cerebral cortex, basal forebrain, progenitor cells, cell fate, cell migration

The traditional view of cerebral cortical development, in which it arises solely from endogenous germinal zones, has been altered by recent studies demonstrating that some cortical cells originate in the basal forebrain (de Carlos et al., 1996; Anderson et al., 1997; Tamamaki et al., 1997; Tan et al., 1998;Lavdas et al., 1999; Wichterle et al., 1999; Anderson et al., 2001). The earliest migrating cells, starting at approximately embryonic day 12 (E12), appear to come from the medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) and migrate robustly into the ventricular (VZ), subventricular (SVZ), and intermediate zones (Lavdas et al., 1999; Wichterle et al., 1999; Anderson et al., 2001). A second migration starts at approximately E14, appears to come from the lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE), and has a more confined migratory route into the SVZ and VZ (Anderson et al., 1997, 2001). The homeobox gene dlx is expressed primarily by ventral cells and is functionally involved in their migration (Anderson et al., 1997). Many of the immigrant cells differentiate into GABAergic interneurons, however not all dlx-positive cells acquire this fate, and some remain in a mitotic state (Anderson et al., 2001). These findings encouraged us to assess the fate of other dlx-positive cells in the cortex. Because their destinations include developing white matter tracts, we examined whether some of the basal cells are of the oligodendrocyte lineage.

The idea of a basal (ventral) origin for forebrain oligodendrocytes is appealing given that in the spinal cord oligodendrocytes originate in the ventral VZ and migrate dorsally to colonize spinal white matter tracts (Orentas and Miller, 1996). Oligodendrocytes are stimulated to develop in the ventral region of the cord by sonic hedgehog (shh), and neuregulin, produced by notochord and floor plate (Pringle et al., 1996; Richardson et al., 1997; Orentas et al., 1999; Vartanian et al., 1999). In the brain, detection of the early oligodendrocyte markers PDGF-α receptor and plp/DM20 also suggests a few localized, primarily ventral sites of origin (Spassky et al., 2000). In the early mouse forebrain, PDGFR-α expression is seen in the MGE and dorsal thalamus, and plp/DM20 is found in the basal plate of the diencephalon, zona limitans intrathalamica, caudal hypothalamus, entopeduncular area, amygdala, and olfactory bulb (Pringle and Richardson, 1993; Spassky et al., 1998; Nery et al., 2001). Olig-1 and 2, basic helix-loop-helix genes expressed early in oligodendrocyte development are also found in these localized sites, preceded by shh expression (Lu et al., 2000; Zhou et al., 2000; Nery et al., 2001). Hence, the parallels between localized, shh-dependent ventral oligodendrocyte development in spinal cord and in brain are strong, making the idea of an analogous dorsal migration plausible.

In this study we show that the dlx-positive immigrant cells from basal forebrain found in dorsal forebrain regions include oligodendrocyte lineage cells. A clonal analysis indicates that these oligodendrocytes originate from basal forebrain stem cells that also produce abundant GABAergic neurons but are themselves dlx-negative. Hence, these data identify a common progenitor for both neurons and glia that migrate from basal into dorsal forebrain during development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, tissue dissociation, and cell culture

Timed-pregnant Swiss-Webster mice (Taconic, Germantown, NY) were used; the plug date is considered E0. Embryonic forebrain tissue was dissected and enzymatically dissociated in papain, then triturated gently and allowed to settle to produce a single cell suspension containing over 85% viable cells, as described previously (Qian et al., 2000). Single cells were plated at moderate density (30–40 cells/well) or at clonal density (1–5 cells/well) into poly-l-lysine (PLL)-coated Terasaki microwells in serum-free medium containing DMEM (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD) with B-27, N2 (Life Technologies), and 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (Life Technologies). The cells were then incubated at 35°C, 6% CO2, with 100% humidity. Optic nerves from postnatal day 5 (P5) mice were dissected and dissociated in papain (Wang et al., 1998) and plated into PLL-coated Terasaki wells in culture medium.

Immunopanning

P5 rat cortices were dissected and dissociated enzymatically using trypsin (Ingraham et al., 1999). After trituration, the dissociated cell suspension was passed through a mesh membrane to enrich for single cells. The cells were labeled with a mature oligodendrocyte marker, O1 antibody (a gift from Dr. Ken McCarthy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC), which recognizes galactocerebroside, and plated on 35 mm Petri dishes precoated with secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). After several washes, the galactocerebroside-expressing cells attached to the dishes were collected using a sheering buffer and plated into PLL-coated Terasaki microwells. Cells were stained live with O4 antibody (a gift from Dr. Anthony Gard, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL), fixed acutely, and then stained for_dlx_.

Clonal analysis

Dissociated single cells from embryonic mouse cortex, LGE, or MGE were plated and cultured at clonal density in serum-free culture medium [B-27 plus N2 (Life Technologies) plus 10 ng/ml FGF-2] as described previously (Qian et al., 2000). Cells were observed in the inverted microscope and mapped every day for up to 12–13 d, with feeding every 2–3 d. Clones were then processed for immunohistochemistry, using live staining for O4 antibody and fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde before staining for other markers, including NG2, glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), β-tubulin III, RC2 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) and Nestin (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank).

Immunostaining

Cryostat sections. Fixed embryos were frozen in O.C.T. TissueTek on dry ice. We cut 12 μm cryostat sections, then incubated them in a blocking solution of 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS for 15 min before staining for_dlx_ and NG2.

Acutely isolated cells and cultured cells. After dissociation, cells were plated into culture wells for <1 hr for acute staining or cultured for a number of hours or days for later time points. Plated cells were washed with Dulbecco's PBS with calcium and magnesium (CMPBS), fixed in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4, at room temperature for 30 min, and then washed three times with CMPBS. Primary antibodies were diluted in CMPBS with 10% NGS.

Dlx staining. Sections or fixed cells were incubated with a primary dlx antibody (1:40; a gift from Dr. Grace Panganiban, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI) at 4°C overnight. An Alexa 488 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was used or a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) with the ABC/VIP kit (Vector Laboratories).

NG2 staining. Sections or fixed cells were incubated with a primary NG2 antibody (1:400; a gift from Dr. Joel Levine, SUNY, Stony Brook, NY) at room temperature for 1 hr and visualized with a Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME). Some sections were counterstained with DAPI (Molecular Probes) to reveal cell nuclei.

O1 staining. O1-immunopanned cells were incubated with a rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (Biosource, Camarillo, CA).

O4 staining. Cultured live cells were incubated with a primary O4 antibody at room temperature for 30 min. The cells were then fixed and incubated with a rhodamine-conjugated secondary antibody (Biosource).

GAD staining. Fixed cells were incubated with primary GAD antibody (1:2500; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) at room temperature for 2 hr. A biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody was used, and staining was visualized with the ABC/VIP kit.

β-Tubulin III staining. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 100% methanol at −20°C for 5 min and rinsed with PBS before incubating in primary anti-antibody (1:400; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) overnight at 4°C. β-tubulin III staining was visualized with an Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Molecular Probes). For dlx and GAD double-labeling, which both use rabbit antibodies, we take advantage of the fact that the dlx antigen is nuclear while GAD is cytoplasmic. Hence, cells are first stained for GAD, and then GAD-positive cells are mapped and photographed. The cells were then stained for dlx and visualized at high power to examine the nucleus. Single- and double-labeled cells can be clearly identified with this method. The frequency of GAD-positive cells and dlx-positive cells was confirmed by staining sister cultures singly with each marker.

RESULTS

The basal cell marker dlx is expressed in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in embryonic mouse dorsal forebrain white matter

Four dlx genes (dlx 1, 2, 5, and 6) are found in the CNS where they show restricted patterns of expression in ventral forebrain from early stages, indicating that they play a role in differentiation of this region. Dlx 1 and 2 have almost identical expression patterns, being low in the telencephalon at E10, and increasing rapidly in the basal region so that by E12 they are readily detectable in the LGE and MGE, while remaining at extremely low levels in the overlying cerebral cortex (Bulfone et al., 1993; Porteus et al., 1994; Anderson et al., 1997, 2001; Liu et al., 1997; Eisenstat et al., 1999). Dlx 1 and 2 are strongly expressed in progenitor cells, initially in the VZ, and then in the SVZ. Later, as the cells mature, dlx_1 and 2 stimulate expression of_dlx 5 and 6 in the same cells, now located in the SVZ and in the mantle zone (Liu et al., 1997; Eisenstat et al., 1999). To quantify the percentage of dlx-positive cells in the developing mouse cerebral cortex and basal forebrain, we enzymatically dissociated forebrain cells and stained them acutely using an antibody that recognizes_dlx_ 1, 2, 5, and 6 (Panganiban et al., 1997). Fifty-five percent of acutely dissociated LGE cells at E14 are dlx-positive, compared with <1% of cortical cells. Using this antibody we can now trace the development of dlx-positive cells for a longer period than using antibodies that detect dlx1/2 alone. Previous reports of_dlx_1/2 expression revealed a few cells apparently entering the cerebral cortex from basal forebrain areas. In coronal sections of E13–E14 mouse forebrain stained using the pan-dlx antibody, prominent streams of dlx-positive cells from the basal forebrain deep into the cerebral cortex are visible (Fig. 1). One main stream can be tracked into the marginal zone, and the other into the intermediate zone. This clear distribution of dlx-positive cells apparently streaming from basal to dorsal regions provides an image consistent with previous reports documenting basal cell migration into the cortex (de Carlos et al., 1996; Anderson et al., 1997, 2001;Tamamaki et al., 1997; Tan et al., 1998; Lavdas et al., 1999; Wichterle et al., 1999). Because some of the dlx-positive cells were entering regions known to develop into white matter, we decided to examine whether any of the dlx-positive cells contribute oligodendrocytes to cortical white matter tracts.

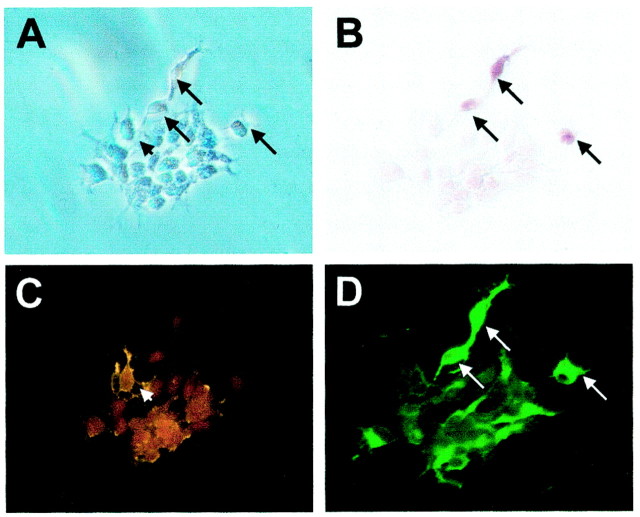

Fig. 1.

Dlx expression in E14 mouse brain.A, Dlx is predominantly expressed in cells in the LGE at E14. Streams of dlx-positive cells are visible leading from basal forebrain into the cerebral cortex (small arrows). A higher magnification of the boxed area in_A_ is shown in B. _Arrows_indicate examples of dlx-positive nuclei entering the intermediate zone of the cortex. CTX, Cerebral cortex; LGE, lateral ganglionic eminence. Scale: A, 1 cm = 182 μm; B, 1 cm = 60 μm.

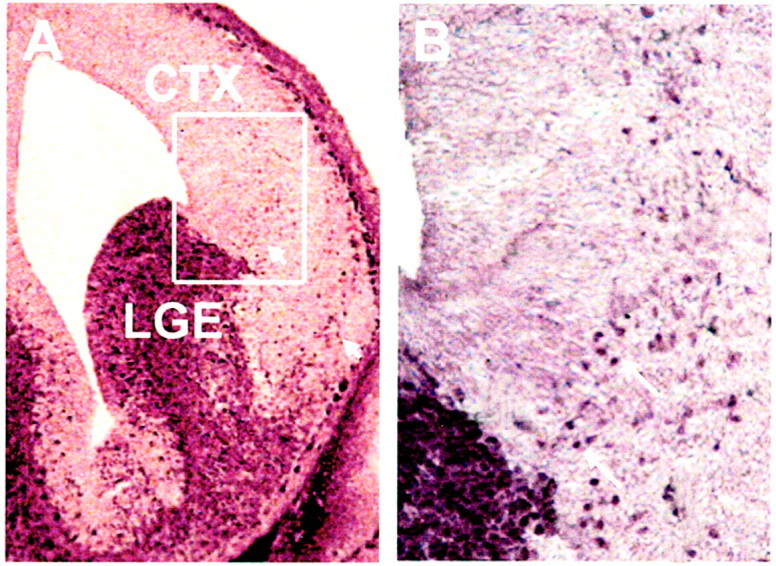

By E18, as shown in Figure 2, dlx-positive cells were detected in three major areas of developing dorsal white matter: subcortical white matter, corpus callosum, and fimbria. In contrast, no dlx-positive cells were detected in the optic tract in the ventral, diencephalic region. The number of dlx-positive cells in these regions of developing white matter was quantified by double labeling the dlx-stained sections with DAPI, which labels cell nuclei. Dlx-expressing cells comprised 5–13% of total cells present in sections of these three areas of dorsal forebrain white matter at E18, but were absent from the optic tract at this age.

Fig. 2.

Dlx expression in developing white matter regions of E18 mouse brain. Low-power micrograph of coronal sections from E18 mouse brain illustrating the major white matter tracts in anterior (A) and posterior (A′) forebrain. CC, Corpus callosum;CWM, subcortical white matter; _FIM,_fimbria; OC, optic chiasm. B, The number of dlx-positive cells in sections of embryonic white matter tracts as a percentage of total cells (examples of staining are shown in_C–F_′). There was a significant difference among the different areas of white matter (ANOVA; p < 0.01)._C–F_′, Examples of different areas of white matter in E18 brain sections stained for dlx (brown) (C–F) and counterstained with DAPI (blue) (_C_′–_F_′). Note that in dlx-positive nuclei, DAPI staining is not visible, hence the total cell number is calculated by adding the number of DAPI-positive and dlx-positive cells. Dlx-positive cells were found in the cortical white matter, corpus callosum, and fimbria, but not in the optic chiasm. Numbers of dlx-positive cells in different forebrain white matter areas are compared in B. Scale: 1 cm = 91 μm.

To examine whether these dlx-positive cells were in the oligodendrocyte lineage, we first double-immunolabeled E18 sections with NG2, a surface marker expressed on early oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (Dawson et al., 2000). Double-labeled cells were visible in the emerging forebrain white matter tracts (Fig. 3). To quantify the double-labeled population, E18 forebrain tissue was enzymatically dissociated to single cells, which were stained acutely (Fig.4). Seventeen percent of cortical and 44% of striatal NG2-positive cells at E18 were dlx-positive. Given that essentially all of the dlx-positive cells that are detected in the cerebral cortex are believed to migrate from basal areas (Anderson et al., 1997, 2001), these data suggest that some of the early oligodendrocyte progenitor cells originate from the basal forebrain.

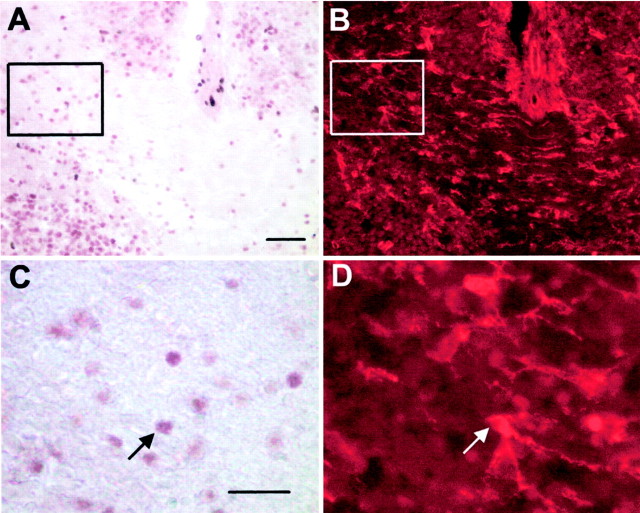

Fig. 3.

NG2-positive cells expressing dlx in E18 mouse corpus callosum. E18 mouse brain sections were stained with anti-dlx and with NG2, a marker expressed by oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. A, B, Low-power light micrograph of the same field of a section of E18 corpus callosum double-labeled for dlx in_brown_ (A) and for NG2 with a Cy3-labeled secondary antibody (B). C, D, High magnification of the boxed areas in_A_ and B, respectively.Arrows indicate a cell double-labeled for dlx and NG2. Scale bars: A, 50 μm; C, 25 μm.

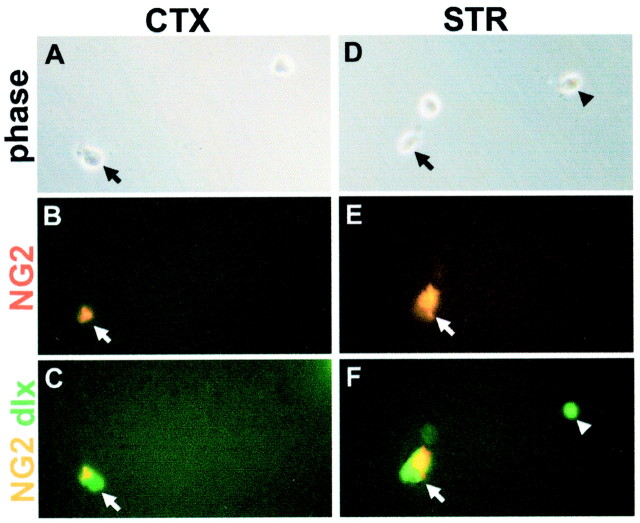

Fig. 4.

NG2-positive cells acutely isolated from E18 mouse forebrain express dlx. E18 cortical and striatal tissue was enzymatically dissociated with papain to single cells, which were fixed acutely and stained for NG2 and dlx. A–C, Cortical cells; D–F, striatal cells. A, D, Phase images of cells acutely isolated from E18 cortex and striatum.B, E, NG2 staining of cells in A and_D_. Arrows indicate NG2-positive cells (red). C, F, Double staining of cells in_A_ and D for NG2 (yellow) and dlx (green).Arrows indicate cells double-labeled for NG2 and dlx.Arrowhead in F indicates a cell that is dlx-positive but NG2-negative. Scale: 1 cm = 46.7 μm.

A subpopulation of postnatal cortical oligodendrocytes expresses the basal cell marker dlx

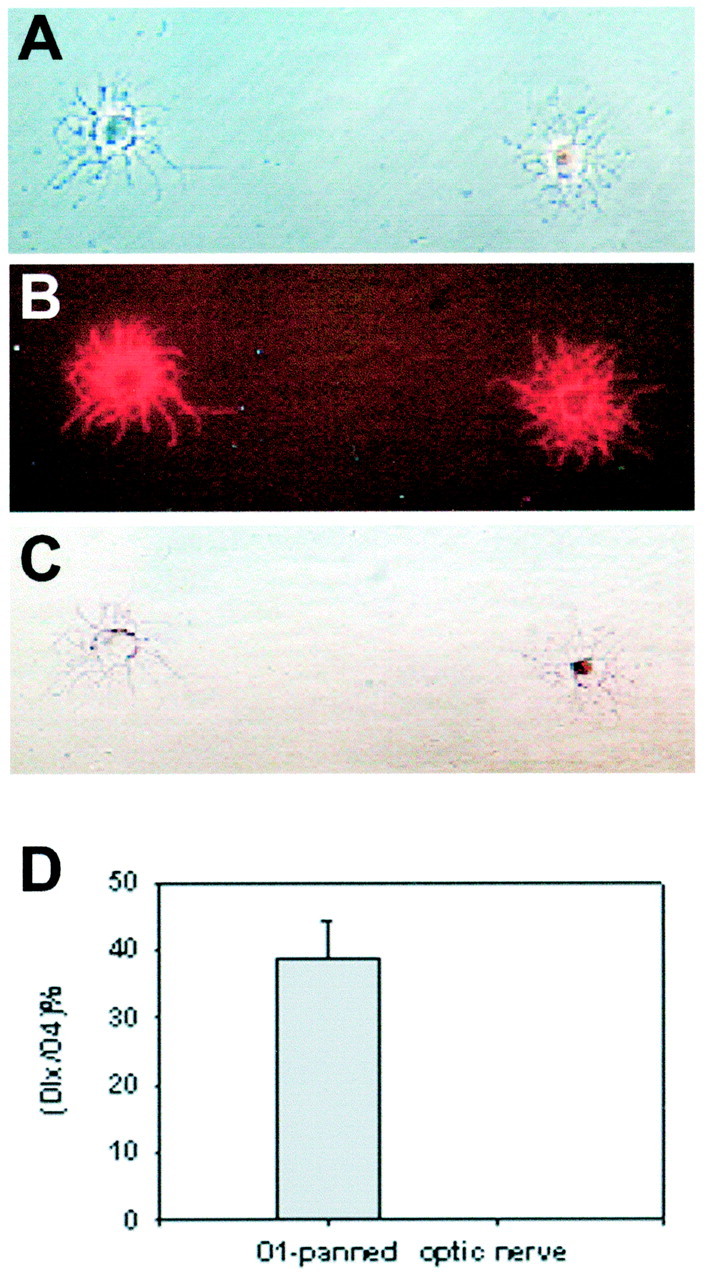

To determine whether these dlx-positive oligodendrocyte progenitor cells developed into mature oligodendrocytes, we examined dlx expression in acutely isolated O1-immunopanned oligodendrocytes from P5 rat cortex. O1 antibody, which recognizes galactocerebroside, labels primarily postmitotic oligodendrocytes (Warrington and Pfeiffer, 1992). As shown in Figure 5, a substantial fraction, nearly 40%, of O1-immunopanned cells expressed the basal cell marker dlx. In contrast, none of the O4-positive or O1-positive oligodendrocytes obtained from the P5 optic nerve expressed dlx. These data indicate that basal-derived oligodendrocyte progenitor cells contribute substantially to the mature oligodendrocyte population in dorsal white matter, migrating into the subcortical white matter, the corpus callosum, and into the fimbria. Because not all basal cells express dlx and because dlx expression is transient, declining with development (Porteus et al., 1994), it is possible that we might have underestimated the contribution of basal oligodendrocytes to dorsal white matter tracts. The fact that no dlx was detectable in optic nerve shows that dlx is not a general marker of developing oligodendrocytes, and that dlx-positive oligodendrocyte lineage cells do not migrate into this region of white matter. These observations suggest that just as basal-derived GABAergic neurons can migrate dorsally into cerebral cortex and even into hippocampus (Anderson et al., 1997; Pleasure et al., 2000), some basal-derived oligodendrocyte lineage cells can migrate long distances into dorsal white matter tracts, including the hippocampal white matter.

Fig. 5.

Dlx expression in O1-immunopanned cortical oligodendrocytes. Postmitotic oligodendrocytes (O1-positive) were immunoselected from P5 rat cerebral cortex. The cells were fixed acutely and stained with O4 antibody to confirm their oligodendrocyte identity and dlx. A, Phase image of two O1-immunoselected P5 cortical cells. B, O4 staining of cells in A. C, The oligodendrocyte on the_left_ is dlx-negative, whereas the one on the_right_ is dlx-positive, with typical nuclear staining.D, The percentage of dlx-positive cells in O1-immunopanned P5 cortical cells was 38%. In contrast, no dlx-positive cells were found in oligodendrocytes isolated from the P5 optic nerve. Scale: 1 cm = 48 μm.

Basal oligodendrocytes arise from multipotent stem cells that produce both neurons and glia

Previous studies in murine spinal cord and cerebral cortex have shown that early in development oligodendrocytes arise from multipotent stem cells, cells that also make neurons. These cells produce neuronal progeny first and glia later. Hence, restricted oligodendrocyte progenitor cells are rare early in development and become abundant at later times (Levison and Goldman, 1997; Rao, 1999; Rogister et al., 1999; Qian et al., 2000). To understand more about the progenitor cells in the basal forebrain that produce oligodendrocytes, we performed a clonal analysis at different embryonic ages.

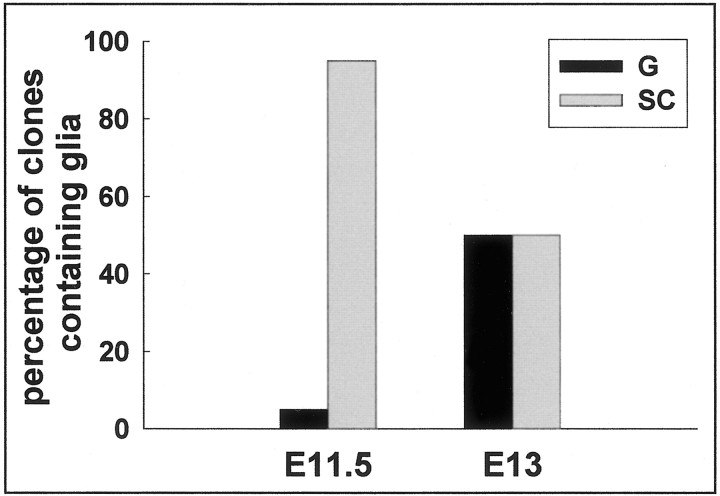

The E11–E14 basal forebrain is composed primarily of dividing progenitor cells. Like the cortical germinal zone, the basal forebrain germinal zone is composed of different types of progenitor cells, including restricted progenitors that produce solely neurons or glia and multipotent stem cells that produce both neurons and glia (Temple, 1989; Reynolds et al., 1992; Birling and Price, 1998). By plating single progenitor cells from basal forebrain in a standardized culture environment and following their division and differentiation in vitro, we could assess whether the cells that produced oligodendrocytes were restricted to that lineage or whether they were multipotent. Single cells from E11.5–E13.5 basal forebrain were plated at clonal density in Terasaki wells, and clones were followed for 5–12 d. The clones were then stained for NG2 or O4 to label oligodendrocyte lineage cells and for β-tubulin III to label neuronal progeny. When clones derived from E11.5 cells were analyzed by this method, we found that 95% of basal forebrain (LGE) progenitors that gave rise to oligodendrocytes were multipotent stem cells that produced both neurons and glia, whereas only 5% were restricted progenitor cells that generated solely glia. By E13.5 however, 50% of the oligodendrocyte-generating progenitor cells were multipotent stem cells, whereas 50% were restricted glioblasts (Fig.6). These data suggest that at early stages, multipotent stem cells are the main source of oligodendrocytes in the basal forebrain region and that they produce restricted glial progenitor cells that begin to predominate at later stages, as shown previously for spinal cord and cerebral cortex. We conclude that oligodendrocytes found in dorsal white matter that express the basal marker dlx originate from basal forebrain multipotent stem cells.

Fig. 6.

Oligodendroglia generating progenitor cells derived from E11.5 and E13 basal forebrain. Progenitor cells were isolated from basal forebrain and plated at clonal density and followed in culture for 5–12 d before staining for NG2 or O4 and β-tubulin III. Note that progenitor cells giving purely glial progeny were very rare at young ages and increased with development from E11.5 to E13. Hence, at early ages most oligodendrocytes arise from stem cells that also make neurons. G, Pure glial clones;SC, stem cell clones.

Stem cells from basal forebrain preferentially generate GABAergic neurons and oligodendrocytes

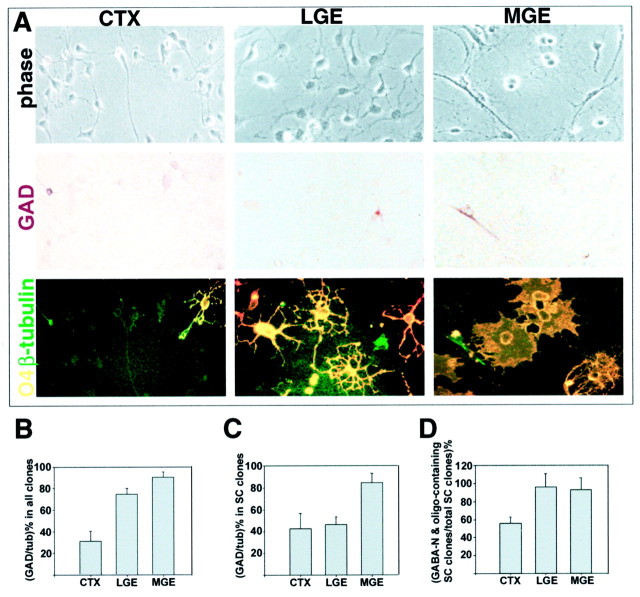

Given that both GABAergic neurons and oligodendrocytes migrate into the cerebral cortex and that the oligodendrocytes arise from basal stem cells, we asked whether the basal stem cells were a common precursor for these two types of cells. Hence, we examined the neuron and glial content of clones derived from single progenitor cells from E12–E14 cortex, LGE and MGE using the marker GAD to identify GABAergic neurons (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

A clonal analysis of stem cells from dorsal and basal E13 forebrain reveals differences in their production of GABAergic neurons and oligodendrocytes. A, Progenitor cells were isolated from three forebrain regions at E13: cortex (CTX), lateral ganglionic eminence (LGE), and medial ganglionic eminence (MGE). The cells were cultured for 12 d and stained for GAD, O4, and β-tubulin III. Stem cell (SC) clones that contained both GABAergic neurons and oligodendrocytes were found in all three regions, as illustrated in A. β-tubulin III-positive neurons are shown in green, O4-positive oligodendrocytes in yellow, and GAD-positive neurons in_brown_. Scale: 1 cm = 58 μm.B, The number of GAD-positive neurons expressed as a percentage of total neurons produced by progenitor cells from cortex, LGE, and MGE. There is a significant difference between the percentage of GAD-positive neurons made by cortical progenitors and the percentage made by LGE or MGE progenitor cells (ANOVA analysis;p < 0.001). tub, β-tubulin III.C, The number of GAD-positive neurons expressed as a percentage of total neurons produced within stem cell clones was calculated. MGE stem cells generated significantly more GAD-positive neurons than LGE or cortical stem cells (ANOVA analysis;p < 0.05). D, The percentage of stem cell clones containing both GABAergic neurons and oligodendrocytes was calculated for the three forebrain regions. LGE and MGE produced significantly more stem cell clones containing both these cell types than did cortex (ANOVA analysis; p < 0.05).GABA-N, GABAergic neuron; oligo, oligodendrocyte.

Comparing the types of neuron produced by the progenitor populations as a whole, we found that basal forebrain progenitor cells produced significantly more GABAergic neurons than cortical progenitor cells: 91 ± 5% of total neurons developing from E12–E14 MGE progenitor cells were GAD-positive, compared with 75 ± 5% from LGE and only 31 ± 9% from cortex (Fig. 7B). This is consistent with in vivo studies showing 80–90% of neurons in the basal ganglia are GABAergic, compared with 20–40% of neurons in the cortex (Hendry et al., 1987; Smith and Bolam, 1990; Graybiel, 1990;Parnavelas, 1992; Kita, 1993)

We then examined the stem cell clones within the dorsal and basal forebrain progenitor cell populations (Fig. 7). Of the total E13 cells plated, the percentage of stem cell clones generated under these conditions was similar for all three regions, with a slight increase in frequency from basal to dorsal: 5.7% for MGE, 8.3% for LGE, and 11.6% for cortex. Within stem cell clones, the proportion of GAD-positive neurons decreased from basal to dorsal areas: 85% of the neurons in MGE clones were GAD-positive, compared with 46% for LGE and 42% for cerebral cortex (Fig. 7C). Basal stem cells from E13 MGE and LGE were significantly more likely (1.5-fold) to contain both GAD-positive neurons and oligodendrocytes than stem cells from E13 cortex (Fig. 7D). Thus, although LGE stem cell clones only contained 46% GAD-positive neurons, similar to the proportion for cortical stem cell clones, they were more likely than cortical clones to contain both these cell types. Taken together, these data indicate that basal forebrain progenitor cells are primed to make GABAergic neurons and oligodendrocytes.

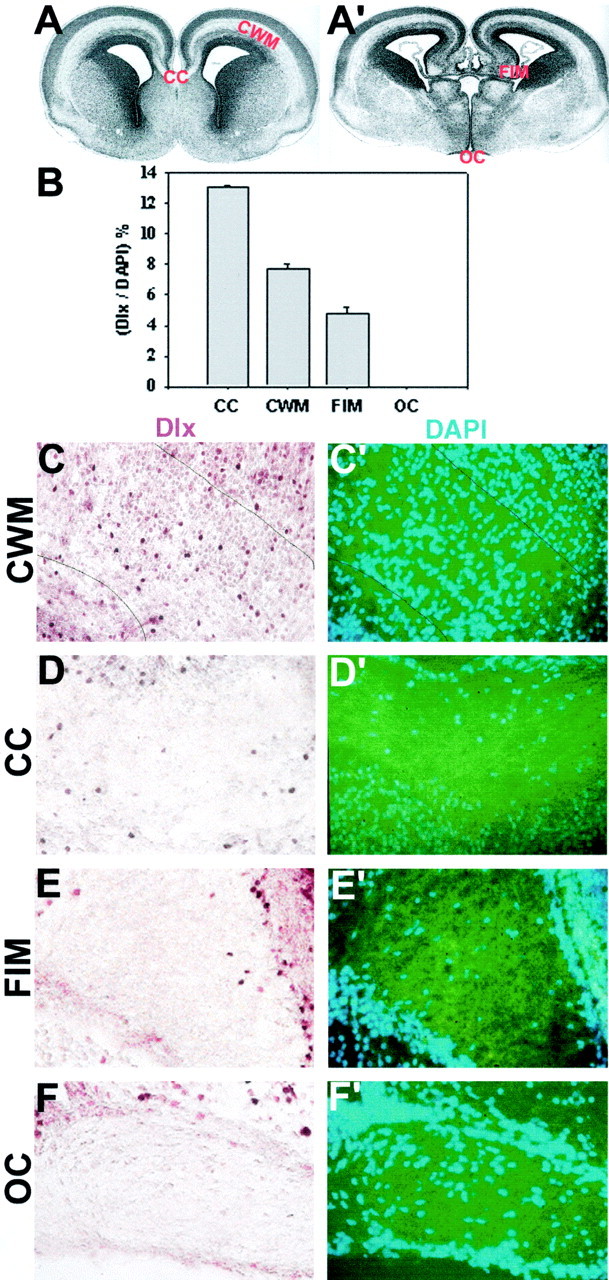

To examine the dlx expression within basal stem cell clones, we stained developing clones growing in serum-free medium supplemented with FGF2 for dlx and cell-type-specific markers (Fig.8). After 5 d, stem cell clones were identified as rapidly growing clones that contained β-tubulin III-positive neuronal progeny, NG2-positive glial progenitor cells, and dividing stem cells that are negative for these markers but positive for the progenitor markers nestin and RC2. These criteria have been shown to characterize stem cell clones in these cultures (Davis and Temple, 1994; Qian et al., 2000) (our unpublished observations). The clones were then examined immunohistochemically for dlx expression. In all cases, dlx expression overlapped with the differentiation markers used, β-tubulin III and NG2, whereas progeny that were negative for these markers did not stain for dlx, suggesting basal stem cells are dlx-negative.

Fig. 8.

Dlx expression in a developing stem cell clone. Single cells from E13 forebrain were dissociated and plated at clonal density. Growing clones were mapped and followed every day for 5 d. Stem cell clones were stained for NG2 to identify glial progeny and β-tubulin III to identify neurons and dlx. A, Phase micrograph of a developing stem cell clone at 5 d in vitro. B, After staining for dlx, three cells are positive, as indicated by arrows. _C,_Membranous NG2 staining of the same clone (small arrow_points to an NG2-positive cell seen in phase in A and in_red fluorescence in C). _D,_β-tubulin III staining of the same clone (_arrows_indicate that the three dlx-positive cells seen in B are also β-tubulin III-positive). Scale: 1 cm = 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

A basal origin for dorsal forebrain oligodendrocytes

Our observation of numerous dlx-positive cells that coexpress early and mature oligodendrocyte markers in developing forebrain white matter indicates that ventral tissue may normally be a substantial source of dorsal forebrain oligodendrocytes. This augments previous findings of localized ventral sites of oligodendrocyte origin in the forebrain (Thomas et al., 2000; Nery et al., 2001). Why was an oligodendrocyte fate not noted previously for cells migrating from basal populations? Dlx_1/2 has not been shown to overlap with oligodendrocyte markers, however the antibody we used recognizes both the early ventral markers dlx 1/2 and the later markers_dlx 5/6, which appear in more mature ventral cells (Anderson et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1997; Eisenstat et al., 1999). This may have allowed us to colocalize dlx expression with the later-appearing oligodendrocyte markers. Although _dlx_1/2 knock-out animals clearly have reduced GABAergic cells in the cerebral cortex, an influence on oligodendrocyte production might have gone undetected because the mutants die around birth, before the major onset of oligodendrocyte generation begins (Anderson et al., 1997).

The specific site of origin of dlx-positive dorsal forebrain oligodendrocytes is not clear: whether LGE, MGE, or from more caudal CNS sites that express this marker. In the Nkx2.1 mutant mouse, in which MGE is converted to LGE, there is a dramatic loss of oligodendrocytes (Sussel et al., 1999; Nery et al., 2001), suggesting that MGE is a more significant source of oligodendrocytes in vivo than LGE. Our observation that dlx-positive cells are not found in the optic tract suggests that migrations of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells are regulated: hence, specific tracts may acquire oligodendrocytes from particular regional sources. Whether all dorsal forebrain oligodendrocytes arise from basal forebrain is not clear. In culture, isolated stem cell clones derived from the cerebral cortex from as early as E10 make abundant oligodendrocytes, even without addition of sonic hedgehog (Qian et al., 2000). However, whether they do so in vivo is not known. We did find a small percentage of NG2-positive cells from E18 mouse cerebral cortex that expressed Pax 6, which labels largely dorsal forebrain areas (Stoykova et al., 1996) (data not shown), suggesting that some cortical oligodendrocytes might be produced from endogenous dorsal stem cells. More extensive studies with specific regional markers should ascertain the specific origin of oligodendrocytes in different white matter tracts. These data suggest that white matter may be regionally chimeric, and thus imply a structural basis within white matter tracts that has not been appreciated previously.

Multipotent stem cells may be the basal source for GABAergic interneurons and oligodendroglia that migrate into the cerebral cortex

Previous studies in developing spinal cord and cerebral cortex indicate that oligodendrocytes arise from multipotent stem-like cells that also generate neurons (Williams et al., 1991; Levison and Goldman, 1997; Rogister et al., 1999; Qian et al., 2000). There are no indications of restricted oligodendrocyte progenitor cells present at very early times: these only arise later after they have been generated from stem cells. Our studies indicate that the same scenario applies to the LGE and MGE; perhaps it is general for the entire CNS. Hence, dlx-expressing oligodendrocytes found in the cerebral cortex come originally from basal stem cells.

The fact that LGE and MGE stem cell clones usually contained both GABAergic neurons and oligodendrocytes suggests that this stem cell may be a common precursor for both of these cell types that migrate from localized sites of origin. In the Nkx2.1 mouse, there is a dramatic loss of both oligodendrocyte lineage cells and GABA cells (Sussel et al., 1999; Nery et al., 2001). This could reflect disruption in the formation or differentiation of a common precursor for interneurons and oligodendrocytes; it would be interesting to examine the stem cell population in these mutants. Alternatively, it is possible that although basal stem cells are a source of both GAD-positive neurons and oligodendrocytes, the GAD-positive neurons produced by these cells remain in the basal forebrain, whereas GAD-positive neurons made by other types of basal progenitor cells migrate into the cortex. This seems unlikely given that basal stem cells make GAD-positive neurons that express dlx, a protein that is necessary for migration into dorsal areas. Moreover, when we made time-lapse recordings of basal forebrain stem cells, we noted that they generated very motile neuronal and glial progeny, so that it was more difficult to follow lineage patterns from these clones than from dorsal clones (data not shown). This high motility, which has been described for basal forebrain cells previously (Wichterle et al., 1999), is consistent with the idea that basal stem cells generate progeny that migrate.

These studies indicate that stem cells from dorsal and basal forebrain areas are different, with the most prominent differences seen between MGE and cerebral cortex; for example MGE stem cells make twice as many GAD-positive neurons. These differences may indicate intrinsic heterogeneity among stem cell populations, either because of regional differences or developmental stage. One interpretation of these data is that ventral and dorsal signals act on stem cells to make them generate particular, region-appropriate cell types. Hence, basal forebrain stem cells are biased early in development to generate GAD-positive neurons that predominate in basal forebrain CNS areas. By allowing these ventrally specified, GAD-positive progeny to migrate, this cell type can be added to a different CNS region to enrich its cell composition. Interestingly, in the neonatal and adult forebrain, stem cells in the striatal SVZ are biased to generate interneurons, including GABAergic interneurons (Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1994; Betarbet et al., 1996). Perhaps this reflects regional specification of ancestors of these cells by ventral signals in the embryo or a maintenance of these signals into adulthood.

If indeed basal and dorsal stem cells are regionally specified, we might expect to see early differences in gene expression. In this regard, it is interesting to note that olig-1 and_2_ mRNA expression is seen in ventral forebrain areas as early as E9.5. Given our observation that virtually all basal forebrain oligodendrocytes emanate from stem cells, olig-1 and_2_ expression may turn out to be within the stem cell population. In other words, these transcription factors may be expressed in localized multipotent stem cells as a result of regionalization signals that endow them with the potential to generate oligodendrocytes in the future, a possibility that will be very interesting to investigate.

Intriguingly, there are a number of similarities between immature GABAergic interneurons and oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. They share a number of neuronal characteristics, including channel properties, and have a similar bipolar phenotype (Barres et al., 1990). Both arise at later times in development, and have progenitor cells that exist throughout the lifetime of the organism. They also migrate long distances within the CNS. Interestingly, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells also manufacture GABA, by a different mechanism than interneurons, as well as having GABA uptake mechanisms (Levi et al., 1986; Barres et al., 1990). Perhaps these shared features reflect their common origin. In vivo, adult forebrain SVZ stem cells make largely GABAergic interneurons, whereas after isolation and expansion in culture they can generate abundant oligodendrocytes (Rogister et al., 1999; Nait-Oumesmar et al., 1999; Cao et al., 2001; Akiyama et al., 2001). Does this reflect regulation of a GABAergic or oligodendrocyte fate decision, and if so what factors might direct the fate choice?

Our data indicate that forebrain stem cells do not express dlx. Within stem cell clones, dlx was always found in the later progeny of stem cells—β-tubulin III-positive neurons, NG2-positive glial progenitor cells, or O4-positive lineage cells—but not in the cells that lack these differentiation markers, which include the stem cells. In acute staining of E14 basal forebrain cell suspensions, 55% of LGE cells were dlx-positive; the remaining 45% dlx-negative cells could accommodate the stem cell population. If as we suspect, stem cells are dlx-negative, then proliferating dlx-positive cells that have been seen_in vivo_ in cortical germinal zones around the time of birth (Anderson et al., 2001) may turn out to be dividing oligodendrocyte progenitor cells that exist in these areas throughout life (Levison et al., 1999) rather than stem cells.

The mechanism whereby oligodendrocyte-lineage cells migrate into the overlying cortex is not clear. Glial progenitor cells are highly migratory and disperse widely within the cortical SVZ (Kakita and Goldman, 1999). Given that dlx is functionally involved in GABAergic neuron migration (Anderson et al., 1997), it may well play a similar role in the migration of oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Interestingly, dlx-positive GABAergic cells first appear in the cerebral cortex before dlx-positive glial lineage cells are detected. Cortical stem cells produce neurons first and glial cells later (Qian et al., 2000); perhaps a similar timing mechanism operates within basal stem cells to regulate the time of production and migration of neurons and glia destined for the cerebral cortex. In conclusion, these data indicate that basal forebrain stem cells generate both neuronal and glial progeny that migrate widely within the forebrain. Elucidation of the mechanisms by which these multipotent cells are specified to make GABAergic neurons or oligodendrocytes will be of central importance for understanding forebrain development and maintenance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01 NS33529. We thank Karen Kirchofer and Qin Shen for invaluable comments on this manuscript and Max Su for technical support.

Correspondence should be addressed to Sally Temple, Room TSX 205, Albany Medical College, 47 New Scotland Avenue, Albany, NY 12208. E-mail: Temples@mail.amc.edu or Hew@mail.amc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akiyama Y, Honmou O, Kato T, Uede T, Hashi K, Kocsis JD. Transplantation of clonal neural precursor cells derived from adult human brain establishes functional peripheral myelin in the rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2001;167:27–39. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson SA, Eisenstat DD, Shi L, Rubenstein JL. Interneuron migration from basal forebrain to neocortex: dependence on Dlx genes. Science. 1997;278:474–476. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson SA, Marin O, Horn C, Jennings K, Rubenstein JL. Distinct cortical migrations from the medial and lateral ganglionic eminences. Development. 2001;128:353–363. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barres BA, Koroshetz WJ, Swartz KJ, Chun LL, Corey DP. Ion channel expression by white matter glia: the O-2A glial progenitor cell. Neuron. 1990;4:507–524. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90109-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betarbet R, Zigova T, Bakay RA, Luskin MB. Dopaminergic and GABAergic interneurons of the olfactory bulb are derived from the neonatal subventricular zone. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1996;14:921–930. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(96)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birling MC, Price J. A study of the potential of the embryonic rat telencephalon to generate oligodendrocytes. Dev Biol. 1998;193:100–113. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulfone A, Puelles L, Porteus MH, Frohman MA, Martin GR, Rubenstein JL. Spatially restricted expression of Dlx-1, Dlx-2 (Tes-1), Gbx-2, and Wnt-3 in the embryonic day 12.5 mouse forebrain defines potential transverse and longitudinal segmental boundaries. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3155–3172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-03155.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao QL, Zhang YP, Howard RM, Walters WM, Tsoulfas P, Whittemore SR. Pluripotent stem cells engrafted into the normal or lesioned adult rat spinal cord are restricted to a glial lineage. Exp Neurol. 2001;167:48–58. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis AA, Temple S. A self-renewing multipotential stem cell in embryonic rat cerebral cortex. Nature. 1994;372:263–266. doi: 10.1038/372263a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson MR, Levine JM, Reynolds R. NG2-expressing cells in the central nervous system: are they oligodendroglial progenitors? J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:471–479. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000901)61:5<471::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Carlos JA, Lopez-Mascaraque L, Valverde F. Dynamics of cell migration from the lateral ganglionic eminence in the rat. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6146–6156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06146.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenstat DD, Liu JK, Mione M, Zhong W, Yu G, Anderson SA, Ghattas I, Puelles L, Rubenstein JL. DLX-1, DLX-2, and DLX-5 expression define distinct stages of basal forebrain differentiation. J Comp Neurol. 1999;414:217–237. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19991115)414:2<217::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graybiel AM. Neurotransmitters and neuromodulators in the basal ganglia. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:244–254. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90104-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendry SH, Schwark HD, Jones EG, Yan J. Numbers and proportions of GABA-immunoreactive neurons in different areas of monkey cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1503–1519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-05-01503.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingraham CA, Rising LJ, Morihisa JM. Development of O4+/O1- immunopanned pro-oligodendroglia in vitro. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;112:79–87. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakita A, Goldman JE. Patterns and dynamics of SVZ cell migration in the postnatal forebrain: monitoring living progenitors in slice preparations. Neuron. 1999;23:461–472. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80800-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kita H. GABAergic circuits of the striatum. Prog Brain Res. 1993;99:51–72. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavdas AA, Grigoriou M, Pachnis V, Parnavelas JG. The medial ganglionic eminence gives rise to a population of early neurons in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7881–7888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-07881.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levi G, Gallo V, Ciotti MT. Bipotential precursors of putative fibrous astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in rat cerebellar cultures express distinct surface features and “neuron-like” gamma-aminobutyric acid transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1504–1508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levison SW, Goldman JE. Multipotential and lineage restricted precursors coexist in the mammalian perinatal subventricular zone. J Neurosci Res. 1997;48:83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levison SW, Young GM, Goldman JE. Cycling cells in the adult rat neocortex preferentially generate oligodendroglia. J Neurosci Res. 1999;57:435–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu JK, Ghattas I, Liu S, Chen S, Rubenstein JL. Dlx genes encode DNA-binding proteins that are expressed in an overlapping and sequential pattern during basal ganglia differentiation. Dev Dyn. 1997;210:498–512. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199712)210:4<498::AID-AJA12>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Long-distance neuronal migration in the adult mammalian brain. Science. 1994;264:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.8178174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu QR, Yuk D, Alberta JA, Zhu Z, Pawlitzky I, Chan J, McMahon AP, Stiles CD, Rowitch DH. Sonic hedgehog–regulated oligodendrocyte lineage genes encoding bHLH proteins in the mammalian central nervous system. Neuron. 2000;25:317–329. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nait-Oumesmar B, Decker L, Lachapelle F, Avellana-Adalid V, Bachelin C, Van Evercooren AB. Progenitor cells of the adult mouse subventricular zone proliferate, migrate and differentiate into oligodendrocytes after demyelination. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4357–4366. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nery S, Wichterle H, Fishell G. Sonic hedgehog contributes to oligodendrocyte specification in the mammalian forebrain. Development. 2001;128:527–540. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orentas DM, Miller RH. The origin of spinal cord oligodendrocytes is dependent on local influences from the notochord. Dev Biol. 1996;177:43–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orentas DM, Hayes JE, Dyer KL, Miller RH. Sonic hedgehog signaling is required during the appearance of spinal cord oligodendrocyte precursors. Development. 1999;126:2419–2429. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panganiban G, Irvine SM, Lowe C, Roehl H, Corley LS, Sherbon B, Grenier JK, Fallon JF, Kimble J, Walker M, Wray GA, Swalla BJ, Martindale MQ, Carroll SB. The origin and evolution of animal appendages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5162–5166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parnavelas JG. Development of GABA-containing neurons in the visual cortex. Prog Brain Res. 1992;90:523–537. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63629-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pleasure SJ, Anderson S, Hevner R, Bagri A, Marin O, Lowenstein DH, Rubenstein JL. Cell migration from the ganglionic eminences is required for the development of hippocampal GABAergic interneurons. Neuron. 2000;28:727–740. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porteus MH, Bulfone A, Liu JK, Puelles L, Lo LC, Rubenstein JL. DLX-2, MASH-1, and MAP-2 expression and bromodeoxyuridine incorporation define molecularly distinct cell populations in the embryonic mouse forebrain. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6370–6383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06370.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pringle NP, Richardson WD. A singularity of PDGF alpha-receptor expression in the dorsoventral axis of the neural tube may define the origin of the oligodendrocyte lineage. Development. 1993;117:525–533. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pringle NP, Yu WP, Guthrie S, Roelink H, Lumsden A, Peterson AC, Richardson WD. Determination of neuroepithelial cell fate: induction of the oligodendrocyte lineage by ventral midline cells and sonic hedgehog. Dev Biol. 1996;177:30–42. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qian X, Shen Q, Goderie SK, He W, Capela A, Davis AA, Temple S. Timing of CNS cell generation: a programmed sequence of neuron and glial cell production from isolated murine cortical stem cells. Neuron. 2000;28:69–80. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao MS. Multipotent and restricted precursors in the central nervous system. Anat Rec. 1999;257:137–148. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990815)257:4<137::AID-AR7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reynolds BA, Tetzlaff W, Weiss S. A multipotent EGF-responsive striatal embryonic progenitor cell produces neurons and astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4565–4574. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04565.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richardson WD, Pringle NP, Yu WP, Hall AC. Origins of spinal cord oligodendrocytes: possible developmental and evolutionary relationships with motor neurons. Dev Neurosci. 1997;19:58–68. doi: 10.1159/000111186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogister B, Ben-Hur T, Dubois-Dalcq M. From neural stem cells to myelinating oligodendrocytes. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;14:287–300. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1999.0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith AD, Bolam JP. The neural network of the basal ganglia as revealed by the study of synaptic connections of identified neurones. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:259–265. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90106-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spassky N, Goujet-Zalc C, Parmantier E, Olivier C, Martinez S, Ivanova A, Ikenaka K, Macklin W, Cerruti I, Zalc B, Thomas JL. Multiple restricted origin of oligodendrocytes. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8331–8343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08331.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spassky N, Olivier C, Perez-Villegas E, Goujet-Zalc C, Martinez S, Thomas J, Zalc B. Single or multiple oligodendroglial lineages: a controversy. Glia. 2000;29:143–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoykova A, Fritsch R, Walther C, Gruss P. Forebrain patterning defects in Small eye mutant mice. Development. 1996;122:3453–3465. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sussel L, Marin O, Kimura S, Rubenstein JL. Loss of Nkx2.1 homeobox gene function results in a ventral to dorsal molecular respecification within the basal telencephalon: evidence for a transformation of the pallidum into the striatum. Development. 1999;126:3359–3370. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamamaki N, Fujimori KE, Takauji R. Origin and route of tangentially migrating neurons in the developing neocortical intermediate zone. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8313–8323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08313.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan SS, Kalloniatis M, Sturm K, Tam PP, Reese BE, Faulkner-Jones B. Separate progenitors for radial and tangential cell dispersion during development of the cerebral neocortex. Neuron. 1998;21:295–304. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80539-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Temple S. Division and differentiation of isolated CNS blast cells in microculture. Nature. 1989;340:471–473. doi: 10.1038/340471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas JL, Spassky N, Perez VE, Olivier C, Cobos I, Goujet-Zalc C, Martinez S, Zalc B. Spatiotemporal development of oligodendrocytes in the embryonic brain. J Neurosci Res. 2000;59:471–476. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(20000215)59:4<471::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vartanian T, Fischbach G, Miller R. Failure of spinal cord oligodendrocyte development in mice lacking neuregulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:731–735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang S, Sdrulla AD, diSibio G, Bush G, Nofziger D, Hicks C, Weinmaster G, Barres BA. Notch receptor activation inhibits oligodendrocyte differentiation. Neuron. 1998;21:63–75. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warrington AE, Pfeiffer SE. Proliferation and differentiation of O4+ oligodendrocytes in postnatal rat cerebellum: analysis in unfixed tissue slices using anti-glycolipid antibodies. J Neurosci Res. 1992;33:338–353. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490330218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wichterle H, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Herrera DG, Alvarez-Buylla A. Young neurons from medial ganglionic eminence disperse in adult and embryonic brain. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:461–466. doi: 10.1038/8131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams BP, Read J, Price J. The generation of neurons and oligodendrocytes from a common precursor cell. Neuron. 1991;7:685–693. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou Q, Wang S, Anderson DJ. Identification of a novel family of oligodendrocyte lineage-specific basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Neuron. 2000;25:331–343. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80898-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]