Polymorphisms of the low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5 (LRP5) gene are associated with obesity phenotypes in a large family‐based association study (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

The low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5 (LRP5) gene, essential for glucose and cholesterol metabolism, may have a role in the aetiology of obesity, an important risk factor for diabetes.

Participants and methods

To investigate the association between LRP5 polymorphisms and obesity, 27 single‐nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), spacing about 5 kb apart on average and covering the full transcript length of the LRP5 gene, were genotyped in 1873 Caucasian people from 405 nuclear families. Obesity (defined as body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2) and three obesity‐related phenotypes (BMI, fat mass and percentage of fat mass (PFM)) were investigated.

Results

Single markers (12 tagging SNPs and 4 untaggable SNPs) and haplotypes (5 blocks) were tested for associations, using family‐based designs. SNP4 (rs4988300) and SNP6 (rs634008) located in block 2 (intron 1) showed significant associations with obesity and BMI after Bonferroni correction (SNP4: p<0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively; SNP6: p = 0.002 and 0.003, respectively). The common allele A for SNP4 and minor allele G for SNP6 were associated with an increased risk of obesity. Significant associations were also observed between common haplotype A–G–G–G of block 2 with obesity, BMI, fat mass and PFM with global empirical values p<0.001, p<0.001, p = 0.003 and p = 0.074, respectively. Subsequent sex‐stratified analyses showed that the association in the total sample between block 2 and obesity may be mainly driven by female subjects.

Conclusion

Intronic variants of the LRP5 gene are markedly associated with obesity. We hypothesise that such an association may be due to the role of LRP5 in the WNT signalling pathway or lipid metabolism. Further functional studies are needed to elucidate the exact molecular mechanism underlying our finding.

Low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5 (LRP5), consisting of 23 exons and spacing 136.6 kb, is mapped to chromosome 11q13.4 in humans and is part of the low‐density lipoprotein receptor family of cell surface receptors.1,2LRP5 plays an important part in the WNT signalling pathway,3,4,5,6 may regulate bone and eye development,7,8 and is important for glucose and cholesterol metabolism.9

Obesity is a growing healthcare problem and risk factor for common diseases such as type 2 diabetes, heart diseases and hypertension. The prevalence of obesity has increased so rapidly that the obese population in developed countries has more than doubled over the past decade.10 A marked parallel increase in the prevalence of obesity‐related disorders, such as diabetes, is seen worldwide.11

Although a genetic determination of obesity has been established, with estimates of heritability >0.50 for the variation in body mass index (BMI), fat mass and percentage of fat mass (PFM),12,13,14,15,16 the underlying susceptibility genes remain largely unknown. LRP5 polymorphisms have been found important to complex diseases or traits that are related to obesity.1,8,9,17,18,19,20 However, the direct relationship between LRP5 and obesity has never been studied. Given the role of LRP5 in obesity‐related metabolic pathways and diseases, we hypothesise and test in this study that LRP5 is associated with obesity phenotypes.

Study design and methods

Participants

The study was approved by the Creighton University Institutional Review Board. Signed informed consent was obtained from all study participants before they entered the study. The study participants came from an expanding database created for ongoing studies in the Osteoporosis Research Center of Creighton University, Omaha, Nebraska, USA, to search for genes underlying common human complex traits, including obesity and osteoporosis. The study design and recruitment procedures have been published previously.21 In all, 405 nuclear families (family size ranged from 3 to 12, average 4.62) with 1873 people were analysed in this study, including 740 parents, 389 male children and 744 female children. All of the participants were Midwestern US Caucasians of European origin.

Genotyping

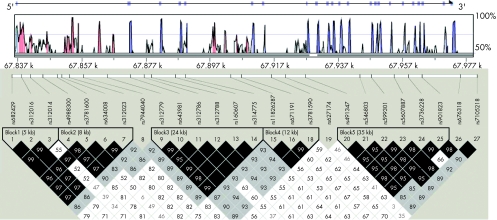

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using a commercial isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) following the procedure detailed in the kit. DNA concentration was assessed by a DU530 UV/VIS Spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, California, USA). A total of 41 SNPs within and around LRP5 were selected on the basis of the following criteria: (1) validation status (validated experimentally in human populations), especially in Caucasians, (2) an average density of 1 SNP per 3 kb, (3) degree of heterozygosity—that is, minor allele frequency (MAF) >0.05, (4) functional relevance and importance, and (5) reported to the dbSNP (SNP database) by various sources. Twenty seven SNPs were successfully genotyped using the high‐throughput BeadArray SNP genotyping technology of Illumina (San Diego, California, USA). The average rate of missing genotype data was approximately 0.05%. The average genotyping error rate estimated through blind sample duplication was <0.01%. The 27 SNPs successfully genotyped were spaced about 5 kb apart on average and covered the full length (including upstream and downstream of potential regulatory regions) of the LRP5 gene (fig 1).

Figure 1 Gene structure, conservation sequence analysis and linkage disequilibrium (LD) block structure for LRP5. The top black line, with arrow indicating the transcription direction and all exons in purple vertical bars, shows the gene structure. The top frame shows conservation domains shared by both the human and mouse genomic sequences. The homology rate between human and mouse is on the vertical axis; the light blue line indicates a homology rate of 75%; the horizontal axis is the physical distance on the human LRP5 gene. The untranslated regions (UTRs) are indicated in light green, and the conserved non‐coding region is in red. LD block structure, as depicted by Haploview, is shown in the bottom frame. The colour from white to black represents the increasing strength of LD. Values for D′ = 1 are dark black boxes and D′<1 (indicated as original value ×100) are shown in the cells.

Phenotype measurement

BMI was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m). Weight was measured in light indoor clothing, using a calibrated balance beam scale, and height was measured using a calibrated stadiometer. Fat mass was measured by dual‐energy x ray absorptiometry with a Hologic 4500 machine (Hologic INC, Bedford, MA, USA). PFM was calculated as the ratio of fat mass to body weight. The measurement precisions of weight, height and fat mass, as reflected by the coefficient of variation, were 1.2%, 0.9% and 2.2%, respectively. We defined obesity as a dichotomous trait using the World Health Organization criterion (obese, BMI >30 kg/m2; and non‐obese, BMI<30 kg/m2).

Statistical analyses

PedCheck22 was used to check Mendelian consistency of SNP genotype data, and any inconsistent genotypes were removed. Then the error‐checking option embedded in Merlin23 was run to identify and disregard the genotypes flanking excessive recombinants, further reducing genotyping errors. The Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for each SNP was tested in parents using the PEDSTATS procedure implemented in Merlin.

Linkage disequilibrium block structure was examined by the program Haploview.24 The D′ values for all pairs of SNPs were calculated and the haplotype blocks estimated using the confidence interval method.25 SNPs with low MAF may inflate estimates of D′ and the use of confidence‐bound estimates for D′ reduces this bias. The default settings were used in these analyses, which invoked a one‐sided upper 95% confidence bound of D′>0.98 and a lower bound of >0.7 to define SNP pairs in strong linkage disequilibrium. A block is identified when at least 95% of SNP pairs in a region meet these criteria for strong linkage disequilibrium. Haplotypes were reconstructed and their frequencies estimated using an accelerated expectation–maximisation algorithm similar to the partition–ligation method26 implemented in Haploview. Haplotype tag SNPs were selected by Haploview on a block‐by‐block basis.

For association analyses, quantitative traits were adjusted for age and sex. Initially, tag SNPs for each block as well as untaggable SNPs (which do not belong to any haplotype block) were tested for single‐marker allelic association, by using family‐based association analysis (FBAT) V.1.55.27 The additive genetic model was applied as it performs well even when the true genetic model is not an additive one.27,28,29 The allelic association examines the transmission of the interested markers from parents to the affected (obese as defined earlier) offspring. The null hypothesis here is no linkage and there is no association between the marker and any obesity susceptibility locus. The ‐o flag was used to minimise the variance of the FBAT statistic. Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for the multiple testing, with the single test significance level established as α = 0.05 divided by the number of tests.

The haplotype version of FBAT (HBAT)30 was used to test the association between phenotypes and within‐block haplotypes. For each block, haplotype‐specific analysis (ie, each haplotype was tested against all others) was first carried out to find the highest‐risk haplotype. Similar to FBAT, HBAT is robust to population admixture, phenotype distribution mis‐specification and ascertainment bias. To account for the multiple haplotypes in each block, empirical global (multihaplotype) p values were obtained through 10 000 permutations using the program HBAT, which is computed by using Monte Carlo samples from the null distribution of no linkage and no association.30

FBAT and HBAT were also carried out in sex‐stratified (for offspring of the nuclear families) subsamples. In addition, population‐based association analysis was carried out in the parental group (for unrelated people) using the PROC generalised linear model (GLM) section of SAS V.8.0e. Normality tests for the quantitative obesity phenotypes (BMI, fat mass, PFM) were conducted and data normalised before running the GLM procedure.

Results

Table 1 summarises the basic characteristics of the studied sample stratified by sex. The unadjusted mean trait values of BMI, fat mass and PFM between men and women were significantly different, as assessed by the t test (p<0.001). Women had higher mean fat mass and PFM, but men had a higher mean BMI. Among the 1873 participants, 262 women (125 mothers, 137 daughters) and 193 men (119 fathers, 74 sons) were obese. Table 2 shows marker information, including the name, chromosomal position and MAF for SNPs successfully genotyped. SNP17, which has MAF<0.01, was discarded for subsequent analyses according to common practice.31 We found no significant deviation from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium for all SNPs (table 2). Less than 0.02% of the overall 50 571 genotypes, namely <11 genotypes, were omitted for LRP5 gene because of the violation of Mendelian Law of Inheritance.

Table 1 Descriptive characteristic of study participants from 405 nuclear families.

| Variable | n | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||

| Height (m) | 680 | 1.78 | 0.07 |

| Weight (kg) | 684 | 88.96 | 15.66 |

| Age (years) | 747 | 48.93 | 17.24 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 678 | 22.43 | 8.36 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 680 | 27.94 | 4.50 |

| PFM (%) | 674 | 24.75 | 0.61 |

| Women | |||

| Height (m) | 1039 | 1.64 | 0.06 |

| Weight (kg) | 1043 | 71.54 | 16.07 |

| Age (years) | 1118 | 46.69 | 26.83 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 1034 | 25.88 | 10.42 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1037 | 26.53 | 5.84 |

| PFM (%) | 1026 | 34.98 | 0.70 |

Table 2 General information for the studied single‐nucleotide polymorphisms of low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5.

| SNP | Name | Position | Alleles* | HW p value† | MAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rs682429 | 67835895 | A/G | 0.420 | 0.286 |

| 2 | rs312016 | 67838979 | G/A | 0.412 | 0.286 |

| 3 | rs312014 | 67841538 | G/C | 0.312 | 0.385 |

| 4 | rs4988300 | 67845407 | A/C | 1 | 0.495 |

| 5 | rs3781600 | 67849913 | G/C | 0.549 | 0.090 |

| 6 | rs634008 | 67851317 | A/G | 0.975 | 0.471 |

| 7 | rs312023 | 67853625 | A/G | 0.975 | 0.471 |

| 8 | rs7944040 | 67857932 | A/G | 0.336 | 0.435 |

| 9 | rs312779 | 67865252 | G/A | 0.730 | 0.401 |

| 10 | rs643981 | 67872340 | G/A | 0.291 | 0.408 |

| 11 | rs312786 | 67876553 | C/A | 0.146 | 0.297 |

| 12 | rs312788 | 67878871 | A/C | 0.280 | 0.408 |

| 13 | rs160607 | 67886182 | G/A | 0.292 | 0.406 |

| 14 | rs314775 | 67889307 | A/G | 0.280 | 0.408 |

| 15 | rs11826287 | 67903237 | A/G | 0.228 | 0.195 |

| 16 | rs671191 | 67906557 | A/G | 0.446 | 0.343 |

| 17 | rs604944 | 67909791 | A/G | 1 | 0.008‡ |

| 18 | rs3781590 | 67915728 | G/A | 0.247 | 0.334 |

| 19 | rs627174 | 67920090 | A/G | 0.875 | 0.161 |

| 20 | rs491347 | 67926264 | A/G | 0.753 | 0.242 |

| 21 | rs546803 | 67942968 | A/G | 0.753 | 0.242 |

| 22 | rs599301 | 67946521 | C/G | 0.184 | 0.323 |

| 23 | rs607887 | 67953537 | G/A | 0.251 | 0.323 |

| 24 | rs3736228 | 67957871 | G/A | 0.212 | 0.145 |

| 25 | rs901823 | 67962154 | A/G | 0.325 | 0.325 |

| 26 | rs676318 | 67973996 | A/G | 1 | 0.072 |

| 27 | rs7105218 | 67979037 | C/A | 0.523 | 0.158 |

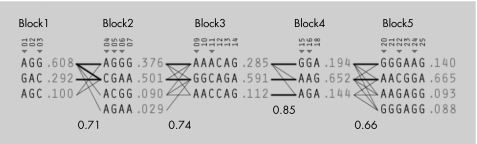

We identified five blocks with high linkage disequilibrium, which ranged in size from 5 to 35 kb (fig 1). Blocks 1 and 2 mainly spanned from promoter to intron 1. Block 3 ranged from introns 1 to 5. Block 4 extended from introns 5 to 7. Block 5 ranged from introns 7 to 19. Twelve tag SNPs were identified. Four SNPs (SNP8, SNP19, SNP26 and SNP27) had low linkage disequilibrium with any other SNPs and could not be assigned to any blocks (untaggable). Figure 2 shows the haplotype structure, diversity and tag SNPs.

Figure 2 Haplotype structure and diversity. Single‐nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) numbers corresponding to fig 1 are listed above each column of alleles; ◂ denotes the tag SNPs. Recombination rates (numbers at the bottom) between adjacent blocks are defined by a multiallelic value of D′. Haplotypes in adjacent blocks are connected by a thick line if they occur with a frequency of >10% and by a thin line if they occur with a frequency of 1–10%. For each SNP, alleles A, T, C and G are indicated.

In all, 16 SNPs (12 tag SNPs and 4 independent SNPs) were used for single‐marker association analysis. The significance level for a single test is therefore set as α = 0.001 (α = 0.05/(16×3) = 0.00104; 16 SNPs, 3 related phenotypes). This correction for multiple testing is overly conservative, as the many SNPs are in high linkage disequilibrium and from the same haplotype block, and the three phenotypes are correlated.

Table 3 shows the single‐marker association results. Among the 16 SNPs, SNP4 in block 2 shows the strongest association across all phenotypes. SNP4 (rs4988300) had a preferential transmission of the common allele A to the obese offspring, with p<0.001. In addition, a significant association was found for BMI with p = 0.001, which remained significant after Bonferroni adjustment. For fat mass and PFM, the p values were 0.006 and 0.038, respectively, indicating a similar trend, although not reaching a significance level after our overly conservative Bonferroni adjustment. In the same block, a significant association was also detected at SNP6, where the minor allele G was overtransmitted to the obese offspring.

Table 3 Single single‐nucleotide polymorphism association results for low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5 polymorphisms.

| Marker | Obesity | BMI | Fat mass | PFM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP1 | 0.032 | 0.077 | 0.064 | 0.368 |

| SNP3 | 0.071 | 0.114 | 0.112 | 0.120 |

| SNP4 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.038 |

| SNP5 | 0.200 | 0.395 | 0.790 | 0.365 |

| SNP6 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.044 |

| SNP8 | 0.106 | 0.035 | 0.241 | 0.997 |

| SNP9 | 0.191 | 0.038 | 0.207 | 0.364 |

| SNP11 | 0.215 | 0.046 | 0.185 | 0.280 |

| SNP15 | 0.247 | 0.494 | 0.876 | 0.624 |

| SNP16 | 0.693 | 0.439 | 1.000 | 0.508 |

| SNP19 | 0.702 | 0.917 | 0.535 | 0.180 |

| SNP20 | 0.350 | 0.417 | 0.649 | 0.719 |

| SNP22 | 0.940 | 0.745 | 0.979 | 0.891 |

| SNP24 | 0.994 | 0.660 | 1.000 | 0.913 |

| SNP26 | 0.919 | 0.330 | 0.460 | 0.281 |

| SNP27 | 0.481 | 0.750 | 0.378 | 0.435 |

Haplotype analysis carried out in each block confirmed the association at the individual SNP level (table 4). Specifically, a common haplotype A–G–G–G (frequency 0.376) in block 2 was significantly associated with obesity phenotypes, with the global p values being p<0.001 for obesity, p<0.001 for BMI, p = 0.003 for fat mass and p = 0.074 for PFM.

Table 4 Associations with obesity phenotypes for lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5 haplotype blocks.

| Block no | Tag SNPs | Highest‐risk haplotype | Frequency | Obesity | BMI | Fat mass | PFM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SNP1, SNP3 | G–A–C | 0.292 | 0.479 | 0.626 | 0.757 | 0.418 |

| 2 | SNP4, SNP5, SNP6 | A–G–G–G | 0.376 | 0.0008 | 0.0007 | 0.003 | 0.074 |

| 3 | SNP9, SNP11 | A–A–C–C–A–G | 0.112 | 0.471 | 0.409 | 0.708 | 0.208 |

| 4 | SNP15, SNP16 | A–G–A | 0.144 | 0.63 | 0.981 | 0.934 | 0.363 |

| 5 | SNP22, SNP24, SNP26 | A–A–C–G–G–A | 0.665 | 0.558 | 0.670 | 0.724 | 0.794 |

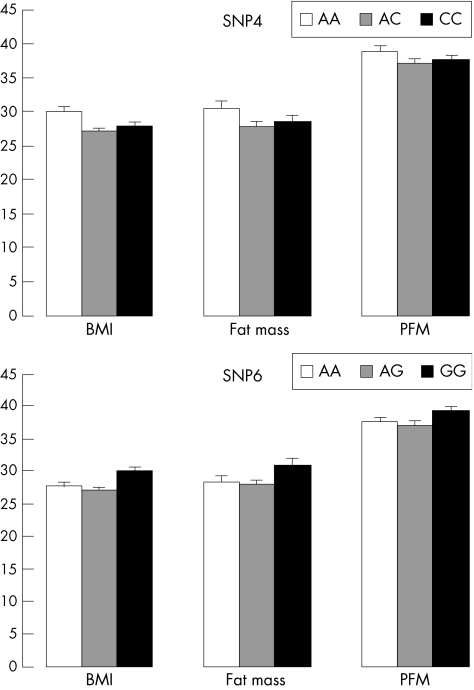

FBAT in sex‐specific subgroups showed that the association between block 2 and obesity was mainly driven by female participants, whereas the signals were non‐significant in men (table 5). GLM analyses of unrelated people further showed that women homozygotic for the overtransmitted allele had larger trait values of BMI, fat mass and PFM, with p values being 0.056, 0.071 and 0.12 for SNP4, and 0.063, 0.098 and 0.13 for SNP6, respectively (fig 3).

Table 5 Sex‐specific association results for low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5 block 2 polymorphisms, including empirical global p values for each tag single‐nucleotide polymorphism (SNP4, SNP6) and the entire block 2.

| Obesity | BMI | Fat mass | PFM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | ||||

| SNP4 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.053 |

| SNP6 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.091 |

| Block2 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| Men | ||||

| SNP4 | 0.090 | 0.142 | 0.461 | 0.237 |

| SNP6 | 0.189 | 0.068 | 0.355 | 0.344 |

| Block2 | 0.110 | 0.244 | 0.131 | 0.209 |

Figure 3 Differences in the phenotypic values of body mass index (BMI; kg/m2), fat mass (kg) and percentage of fat mass (PFM; %) across different genotypes of the single‐nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) loci SNP4 and SNP6. The testing sample consisted of 363 unrelated women from the mothers in the 405 nuclear families. Results are means (standard error) adjusted for age.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt of FBAT of the relationship between LRP5 polymorphisms and obesity. Our purpose is motivated by the multiple lines of evidence showing that the LRP5 may be associated with the aetiology of obesity.

Firstly, Figueroa et al19 found that LRP5 possibly had a role in type 1 diabetes; Fujino et al9 showed that LRP5 was required for cholesterol and glucose metabolism and is an obvious candidate gene for type 2 diabetes. As diabetes and obesity are highly correlated both genetically and phenotypically,11 genes associated with regulating diabetes may also be candidates for obesity. One good example is the vitamin D receptor gene.32,33 Similarly, LRP5 might exert certain effects on both diabetes and obesity.34

Secondly, the marked genetic correlation between obesity phenotypes such as BMI and osteoporosis phenotyes such as bone mineral density was already established, suggesting the existence of common genetic factors contributing to both obesity and osteoporosis.35,36,37,38 In the study sample, we observed significant genetic correlation between BMI and bone mineral density as well (p<0.05 at spine and hip, data not shown). From the molecular perspective, Pei et al38a found the correlation between bone and fat development, and that both adipogenesis and osteogenesis could be mediated by the same molecular pathway.39 Given the overlapping genetic factors for obesity and osteoporosis as well as the key role of the WNT/LRP5 signalling pathway in switching between adipogenesis and osteoclastogenesis,40,41LRP5 could be one of the pleiotropic genetic factors underlying both phenotypes. Thus, it is logical to consider LRP5, an important candidate gene for osteoporosis,18,42,43,44,45 also as a candidate gene for obesity.

In our study, definite associations with various obesity phenotypes were detected for SNP4, SNP6 and their haplotypes in block 2 of LRP5. The consistent relevant findings from analyses of both dichotomous (defined for obese status) and quantitative traits (BMI, fat mass and PFM) strongly supported that LRP5 is important to obesity. However, the mechanism of how the detected major LRP5 polymorphisms (or functional variants being tagged) influence obesity is unknown, although the effect of the associated markers is highly important. We hypothesise that the major block 2 polymorphisms in intron 1 are in linkage disequilibrium with functional variants regulating mRNA production, which may act in the same way as the Sp1 polymorphism in intron 1 of the collagen type I α1 gene.46,47 Bioinformatic analysis using the VISTA program48 to compare the human and mouse LRP5 genomic sequences (>140 kb from the Celera database) showed that the block 2 region was highly conserved (fig 1), suggesting the existence of functional variants in this block that may be the “causal” variants influencing obesity phenotypes. Further molecular genetic studies will be helpful to eventually unravel the myth.

The associations observed in block 2 were found to exist mainly in women, suggesting that some sex‐specific factors might be related to the action of LRP5 on obesity phenotypes. Similar findings have recently been reported for the oestrogen receptor α gene, which was associated with obesity only in women.49 These data suggest the existence of some loci conferring risk for obesity in a sex‐specific manner.

In women, the population‐based associations with obesity for block 2 polymorphisms are borderline significant (p<0.10) but with the trends of association across BMI, fat mass and PFM being consistent (fig 3) with FBAT. Several possible reasons can be given for the only borderline significance in the random sample: potential population stratification may mask the real association50 and, secondly, this might be explained by the lack of statistical power owing to the insufficient sample size of the unrelated group of women.

In summary, we reported the significant association between SNPs and haplotypes in the LRP5 gene with human obesity, suggesting the importance of LRP5 in the pathogenesis of human obesity. Our findings should be stimulating for following up molecular functional studies.

Abbreviations

BMI - body mass index

FBAT - family‐based association analysis

GLM - generalised linear model

HBAT - haplotype version of FBAT

LRP5 gene - low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5 gene

MAF - minor allele frequencies

PFM - percentage of fat mass

SNP - single‐nucleotide polymorphism

Footnotes

Funding: This work was partially supported by grants from NIH (R01 AR050496, K01 AR02170‐01, R01 AR45349‐01 and R01 GM60402‐01A1) and an LB595 grant from the State of Nebraska. The study also benefited from grants from the National Science Foundation of China, Huo Ying Dong Education Foundation, HuNan Province, Xi'an Jiaotong University and the Ministry of Education of China.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Twells R C, Metzker M L, Brown S D, Cox R, Garey C, Hammond H, Hey P J, Levy E, Nakagawa Y, Philips M S, Todd J A, Hess J F. The sequence and gene characterization of a 400‐kb candidate region for IDDM4 on chromosome 11q13. Genomics 200172231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hey P J, Twells R C, Phillips M S, Yusuke N, Brown S D, Kawaguchi Y, Cox R, Guochun X, Dugan V, Hammond H, Metzker M L, Todd J A, Hess J F. Cloning of a novel member of the low‐density lipoprotein receptor family. Gene 1998216103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamai K, Semenov M, Kato Y, Spokony R, Liu C, Katsuyama Y, Hess F, Saint‐Jeannet J P, He X. LDL‐receptor‐related proteins in Wnt signal transduction. Nature 2000407530–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinson K I, Brennan J, Monkley S, Avery B J, Skarnes W C. An LDL‐receptor‐related protein mediates Wnt signalling in mice. Nature 2000407535–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wehrli M, Dougan S T, Caldwell K, O'Keefe L, Schwartz S, Vaizel‐Ohayon D, Schejter E, Tomlinson A, DiNardo S. Arrow encodes an LDL‐receptor‐related protein essential for Wingless signalling. Nature 2000407527–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mao J, Wang J, Liu B, Pan W, Farr GH I I I, Flynn C, Yuan H, Takada S, Kimelman D, Li L, Wu D. Low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein‐5 binds to Axin and regulates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Mol Cell 20017801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Little R D, Carulli J P, Del Mastro R G, Dupuis J, Osborne M, Folz C, Manning S P, Swain P M, Zhao S C, Eustace B, Lappe M M, Spitzer L, Zweier S, Braunschweiger K, Benchekroun Y, Hu X, Adair R, Chee L, FitzGerald M G, Tulig C, Caruso A, Tzellas N, Bawa A, Franklin B, McGuire S, Nogues X, Gong G, Allen K M, Anisowicz A, Morales A J, Lomedico P T, Recker S M, Van Eerdewegh P, Recker R R, Johnson M L. A mutation in the LDL receptor‐related protein 5 gene results in the autosomal dominant high‐bone‐mass trait. Am J Hum Genet 20027011–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gong Y, Slee R B, Fukai N, Rawadi G, Roman‐Roman S, Reginato A M, Wang H, Cundy T, Glorieux F H, Lev D, Zacharin M, Oexle K, Marcelino J, Suwairi W, Heeger S, Sabatakos G, Apte S, Adkins W N, Allgrove J, Arslan‐Kirchner M, Batch J A, Beighton P, Black G C, Boles R G, Boon L M, Borrone C, Brunner H G, Carle G F, Dallapiccola B, De Paepe A, Floege B, Halfhide M L, Hall B, Hennekam R C, Hirose T, Jans A, Juppner H, Kim C A, Keppler‐Noreuil K, Kohlschuetter A, LaCombe D, Lambert M, Lemyre E, Letteboer T, Peltonen L, Ramesar R S, Romanengo M, Somer H, Steichen‐Gersdorf E, Steinmann B, Sullivan B, Superti‐Furga A, Swoboda W, van den Boogaard M J, Van Hul W, Vikkula M, Votruba M, Zabel B, Garcia T, Baron R, Olsen B R, Warman M L. LDL receptor‐related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell 2001107513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujino T, Asaba H, Kang M J, Ikeda Y, Sone H, Takada S, Kim D H, Ioka R X, Ono M, Tomoyori H, Okubo M, Murase T, Kamataki A, Yamamoto J, Magoori K, Takahashi S, Miyamoto Y, Oishi H, Nose M, Okazaki M, Usui S, Imaizumi K, Yanagisawa M, Sakai J, Yamamoto T T. Low‐density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5 (LRP5) is essential for normal cholesterol metabolism and glucose‐induced insulin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003100229–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James P T. Obesity: the worldwide epidemic. Clin Dermatol 200422276–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golay A, Ybarra J. Link between obesity and type 2 diabetes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 200519649–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Provencher V, Perusse L, Bouchard L, Drapeau V, Bouchard C, Rice T, Rao D C, Tremblay A, Despres J P, Lemieux S. Familial resemblance in eating behaviors in men and women from the Quebec Family Study. Obes Res 2005131624–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaprio J, Eriksson J, Lehtovirta M, Koskenvuo M, Tuomilehto J. Heritability of leptin levels and the shared genetic effects on body mass index and leptin in adult Finnish twins. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 200125132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deng H W, Lai D B, Conway T, Li J, Xu F H, Davies K M, Recker R R. Characterization of genetic and lifestyle factors for determining variation in body mass index, fat mass, percentage of fat mass, and lean mass. J Clin Densitom 20014353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y J, Xiao P, Xiong D H, Recker R R, Deng H W. Searching for obesity genes: progress and prospects. Drugs Today (Barc) 200541345–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu P Y, Li Y M, Li M X, Malkin I, Qin Y J, Chen X D, Liu Y J, Deng H W. Lack of evidence for a major gene in the Mendelian transmission of BMI in Chinese. Obes Res 2004121967–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyden L M, Mao J, Belsky J, Mitzner L, Farhi A, Mitnick M A, Wu D, Insogna K, Lifton R P. High bone density due to a mutation in LDL‐receptor‐related protein 5. N Engl J Med 20023461513–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson M L. The high bone mass family—the role of Wnt/Lrp5 signaling in the regulation of bone mass. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 20044135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Figueroa D J, Hess J F, Ky B, Brown S D, Sandig V, Hermanowski‐Vosatka A, Twells R C, Todd J A, Austin C P. Expression of the type I diabetes‐associated gene LRP5 in macrophages, vitamin A system cells, and the Islets of Langerhans suggests multiple potential roles in diabetes. J Histochem Cytochem 2000481357–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruford E A, Riise R, Teague P W, Porter K, Thomson K L, Moore A T, Jay M, Warburg M, Schinzel A, Tommerup N, Tornqvist K, Rosenberg T, Patton M, Mansfield D C, Wright A F. Linkage mapping in 29 Bardet‐Biedl syndrome families confirms loci in chromosomal regions 11q13, 15q22.3–q23, and 16q21. Genomics 19974193–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong D H, Liu Y Z, Liu P Y, Zhao L J, Deng H W. Association analysis of estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms with cross‐sectional geometry of the femoral neck in Caucasian nuclear families. Osteoporos Int 2005162113–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Connell J R, Weeks D E. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet 199863259–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abecasis G R, Cherny S S, Cookson W O, Cardon L R. Merlin—rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet 20023097–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett J C, Fry B, Maller J, Daly M J. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 200521263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gabriel S B, Schaffner S F, Nguyen H, Moore J M, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, Higgins J, DeFelice M, Lochner A, Faggart M, Liu‐Cordero S N, Rotimi C, Adeyemo A, Cooper R, Ward R, Lander E S, Daly M J, Altshuler D. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 20022962225–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin Z S, Niu T, Liu J S. Partition‐ligation‐expectation‐maximization algorithm for haplotype inference with single‐nucleotide polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet 2002711242–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horvath S, Xu X, Laird N M. The family based association test method: strategies for studying general genotype–phenotype associations. Eur J Hum Genet 20019301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knapp M. A note on power approximations for the transmission/disequilibrium test. Am J Hum Genet 1999641177–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tu I P, Balise R R, Whittemore A S. Detection of disease genes by use of family data. II. Application to nuclear families. Am J Hum Genet 2000661341–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horvath S, Xu X, Lake S L, Silverman E K, Weiss S T, Laird N M. Family‐based tests for associating haplotypes with general phenotype data: application to asthma genetics. Genet Epidemiol 20042661–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newton‐Cheh C, Hirschhorn J N. Genetic association studies of complex traits: design and analysis issues. Mutat Res 200557354–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Speer G, Cseh K, Winkler G, Vargha P, Braun E, Takacs I, Lakatos P. Vitamin D and estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms in type 2 diabetes mellitus and in android type obesity. Eur J Endocrinol 2001144385–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye W Z, Reis A F, Dubois‐Laforgue D, Bellanne‐Chantelot C, Timsit J, Velho G. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with obesity in type 2 diabetic subjects with early age of onset. Eur J Endocrinol 2001145181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magoori K, Kang M J, Ito M R, Kakuuchi H, Ioka R X, Kamataki A, Kim D H, Asaba H, Iwasaki S, Takei Y A, Sasaki M, Usui S, Okazaki M, Takahashi S, Ono M, Nose M, Sakai J, Fujino T, Yamamoto T T. Severe hypercholesterolemia, impaired fat tolerance, and advanced atherosclerosis in mice lacking both low density lipoprotein receptor‐related protein 5 and apolipoprotein E. J Biol Chem 200327811331–11336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coin A, Sergi G, Beninca P, Lupoli L, Cinti G, Ferrara L, Benedetti G, Tomasi G, Pisent C, Enzi G. Bone mineral density and body composition in underweight and normal elderly subjects. Osteoporos Int 2000111043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toth E, Ferenc V, Meszaros S, Csupor E, Horvath C. Effects of body mass index on bone mineral density in men. Orv Hetil 20051461489–1493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deng F Y, Lei S F, Li M X, Jiang C, Dvornyk V, Deng H W. Genetic determination and correlation of body mass index and bone mineral density at the spine and hip in Chinese Han ethnicity. Osteoporos Int 200617119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao L J, Liu Y J, Recker R R, Deng H W. Interventions decreasing obesity risk tend to be beneficial for decreasing risk to osteoporosis: a challenge to the current dogma. J Bone Miner Res 20S339

- 38a.Pei L, Tontonoz P. Fat's loss is bone's gain. J Clin Invest 2004113(6)805–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akune T, Ohba S, Kamekura S, Yamaguchi M, Chung U I, Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Harada Y, Azuma Y, Nakamura K, Kadowaki T, Kawaguchi H. PPARgamma insufficiency enhances osteogenesis through osteoblast formation from bone marrow progenitors. J Clin Invest 2004113846–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bennett C N, Ross S E, Longo K A, Bajnok L, Hemati N, Johnson K W, Harrison S D, MacDougald O A. Regulation of Wnt signaling during adipogenesis. J Biol Chem 200227730998–31004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross S E, Hemati N, Longo K A, Bennett C N, Lucas P, Erickson R, MacDougald O. Inhibition of adipogenesis by Wnt signaling. Science 2000289950–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bollerslev J, Wilson S G, Dick I M, Islam F M, Ueland T, Palmer L, Devine A, Prince R L. LRP5 gene polymorphisms predict bone mass and incident fractures in elderly Australian women. Bone 200536599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferrari S L, Deutsch S, Baudoin C, Cohen‐Solal M, Ostertag A, Antonarakis S E, Rizzoli R, de Vernejoul M C. LRP5 gene polymorphisms and idiopathic osteoporosis in men. Bone 200537770–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rawadi G, Roman‐Roman S. Wnt signalling pathway: a new target for the treatment of osteoporosis. Expert Opin Ther Targets 200591063–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clement‐Lacroix P, Ai M, Morvan F, Roman‐Roman S, Vayssiere B, Belleville C, Estrera K, Warman M L, Baron R, Rawadi G. Lrp5‐independent activation of Wnt signaling by lithium chloride increases bone formation and bone mass in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 200510217406–17411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uitterlinden A G, Burger H, Huang Q, Fang Y, McGuigan F E, Grant S F, Hofman A, van Leeuwen J P T M, Pols H A P, Ralston S H. Relation of alleles of the collagen type 1 alpha1 gene to bone density and the risk of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. New Engl J Med 19981016–1021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Grant S F, Reid D M, Blake G, Herd R, Fogelman I, Ralston S H. Reduced bone density and osteoporosis associated with a polymorphic Sp1 binding site in the collagen type I alpha 1 gene. Nat Genet 199614203–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frazer K A, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin E M, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucl Acids Res 200432(Web Server issue)W273–W279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okura T, Koda M, Ando F, Niino N, Ohta S, Shimokata H. Association of polymorphisms in the estrogen receptor alpha gene with body fat distribution. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003271020–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deng H W. Population admixture may appear to mask, change or reverse genetic effects of genes underlying complex traits. Genetics 20011591319–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]