Beyond Insulin Resistance: Innate Immunity in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2013 Mar 8.

Published in final edited form as: Hepatology. 2008 Aug;48(2):670–678. doi: 10.1002/hep.22399

Abstract

Obesity is an inflammatory disorder characterized by heightened activity of the innate immune system. Innate immune activation is central to the development of obesity-related insulin resistance; it also plays an important role in obesity-related tissue damage, such as that seen in atherosclerosis. Recent research has implicated the innate immune system in the pathophysiology of obesity-related liver disease. This review summarizes how innate immune processes, occurring both within and outside the liver, cause not only insulin resistance but also end-organ damage in the form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. (HEPATOLOGY 2008;48:670-678.)

Obesity is the direct result of an imbalance between nutritional intake and energy expenditure, which leads to the storage of excess fuel as fat. Although adipose tissue represents the body's principal lipid storage reservoir, fat can accumulate ectopically in other organs such as muscle and liver. Regardless of its location (even in adipose tissue), excess fat can provoke abnormalities in tissue structure and function that result in end-organ damage. A growing body of evidence supports the concept that end-organ damage in obesity is an inflammatory condition.1 Consequences of this systemic inflammation include type 2 diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).1 With respect to the liver, immune pathways can adversely affect hepatic lipid metabolism and lead to serious outcomes such as hepatic injury, inflammation, and fibrosis. These processes are likely at play in the 72 million obese adults in the United States (www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/07newsreleases/obesity.htm), 75% of whom have fatty livers.2

The leukocytes, receptors, and soluble mediators involved in obesity-related inflammatory sequences are all part of the innate immune system. The evolutionary purpose of innate immunity is to defend against pathogens or foreign substances. In the setting of obesity, however, dietary fats or fatty acids may be perceived as foreign substances that modulate inflammation and its metabolic effects. Although a number of immune responses to fat can occur locally in target tissues, recent studies suggest a novel paradigm in which inflammation in adipose tissue is a master regulator of metabolic and immune dysfunction in other organs. In this context, an important question for the hepatologist is whether immune activation in adipose tissue is a prerequisite for the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Although data are currently incomplete, there is compelling evidence that adipose tissue inflammation exacerbates hepatic steatosis and can heighten innate inflammatory responses within the liver.3,4 In this review, we will summarize evidence that innate immune pathways are activated in obesity and describe the involvement or proposed involvement of these pathways in the pathogenesis of NASH.

Fat-Induced Activation of Proinflammatory Pathways Causes Insulin Resistance

Fat can cause insulin resistance by prompting the activation of select serine kinases within a variety of insulin-sensitive cells. Singly or in combination, these enzymes phosphorylate regulatory serine residues on the insulin receptor substrates IRS-1 and IRS-2, leading to the down-modulation of normal insulin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation and interfering with physiologic insulin responses. A causal connection between fat-related activation of serine kinases and insulin resistance has been demonstrated in adipose tissue5 and muscle6,7 as well as liver.8-11 It occurs quite rapidly in vivo in response to both intravenous fat infusion6,8 and high-fat feeding.9,10 Saturated as well as unsaturated fatty acids are capable of activating the serine kinases that lead to insulin resistance.5,6,8,9,11,12 In the liver, long-chain saturated fatty acids appear to be the most potent species.11,12

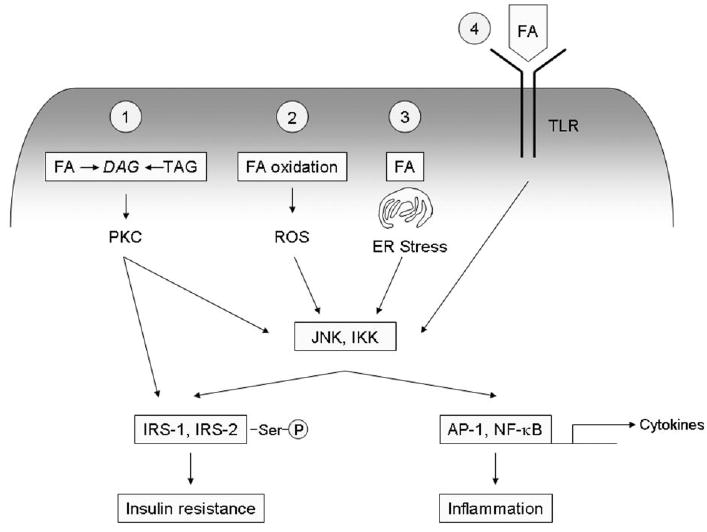

The three serine kinases implicated most strongly in the pathogenesis of fat-induced insulin resistance are Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), inhibitor of nuclear factor _κ_B (NF-_κ_B) kinase (IKK), and novel isoforms of protein kinase C (PKC).13-15 Among these, JNK and IKK are particularly noteworthy proinflammatory signaling molecules. In the setting of obesity, activation of these kinases likely arises through several mechanisms as outlined in Fig. 1. In one scenario, PKC is activated by diacylglycerol formed during the intracellular metabolism of lipids,14 with JNK and IKK being activated downstream of PKC as part of a signaling cascade.5 In a second pathway, intracellular fat activates these kinases independently of PKC as part of an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response.16,17 A third pathway points to reactive oxygen species, which can be generated during fatty acid oxidation, as inducers of JNK and IKK18 Fourth, extracellular fatty acids, by virtue of their resemblance to the lipid moieties of bacterial lipopolysaccharides, can activate IKK by engaging Toll-like receptors (TLRs).19 The fact that all four of these pathways converge at the level of JNK and IKK points to the close interconnection between insulin resistance and inflammation in the setting of obesity. The complexity of the relationship is enhanced even further when one considers that inflammatory cytokines, induced by JNK and IKK, can contribute to a feed-forward amplification of insulin resistance and inflammatory signaling (see below). The pivotal role of inflammatory pathways in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance has been proven by experiments showing that pharmacologic or genetic suppression of inflammatory signaling improves insulin sensitivity.20-22 The role of inflammatory pathways in NAFLD are also under active study, with available data indicating that inflammation plays an etiologic role in hepatic insulin resistance as well as hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis.

Fig. 1.

Activation of inflammatory signaling pathways by fat. Excess fat or fatty acids (FA) can activate a number of intracellular signaling pathways that lead to inflammation through IKK and JNK IKK and JNK cause inflammation by promoting formation of the transcription factors AP-1 and NF-_κ_B, which activate transcription of a host of proinflammatory genes including cytokines, chemokines, and cell adhesion molecules. PKC, IKK and JNK can also cause insulin resistance by promoting aberrant serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and IRS-2. (1) The lipid intermediate diacylglycerol (DAG), formed during the synthesis or hydrolysis of triacylglycerol (TAG), can activate PKC, which causes downstream activation of IKK and JNK. (2) Fatty acid oxidation yields reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can directly activate IKK and JNK. (3) Excess fat can promote ER stress, which activates IKK and JNK through the intermediate kinases IRE-1 and PERK. (4) Extracellular fatty acids can act as ligands for TLR, which signal through IKK and JNK.

Fat-Induced Inflammatory Signals in the Liver and Their Relation to NAFLD

Fatty acids12,23,24 and high-fat feeding9,21,25 can directly induce inflammatory signaling in the liver even in the absence of obesity or systemic insulin resistance.9 Excess fat activates JNK and IKK in hepatocytes, which can induce hepatic insulin resistance, inflammatory cytokine expression, and in some instances cell death.12,20,21,24,26,27 JNK and IKK both have the ability to stimulate the transcription of inflammatory target genes through their activation of activator protein-1 (AP-1) and NF-_κ_B, respectively. Indeed, high-fat feeding in mice induces a hepatic profile of inflammatory gene expression closely mimicking that of mice expressing a hepatocyte-specific IKK transgene,20,21,28 and conversely, mice with a targeted disruption of either IKK or JNK are resistant to diet-induced insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis.20,21,25,27,29 Activation of JNK and IKK in hepatocytes has broad consequences. Directly or indirectly, both kinases promote the expression of lipogenic genes within the liver.25,28,30 Similarly, fat-related activation of IKK/NF-_κ_B and JNK in hepatocytes stimulates the expression of cytokines and cell-adhesion molecules,20,21,27,29 features that likely contribute to steatohepatitis. Indeed, in the methionine-choline-deficient (MCD) model of murine steatohepatitis, blockade of either IKK or the JNK-1 isoform of JNK significantly limits liver injury and inflammation.27,31 Studies indicate that JNK is also an important mediator of “lipotoxicity” in the liver, based on its involvement in saturated fatty acid–induced apoptosis of hepatocytes in in vivo and in vitro mouse models.12,27,32 Taken together, these myriad effects assign an important role to hepatocyte-derived IKK and JNK in inflammatory and cytotoxic pathways in obesity-related NAFLD.

In addition to activating inflammatory signaling directly in hepatocytes, fat stimulates innate immune processes locally within the liver that can result in organ damage. One is the up-regulation of the death receptor Fas, an alteration that correlates directly with disease severity in NAFLD.26,33 Hepatic steatosis not only increases Fas expression by hepatocytes but also enhances the vulnerability of hepatocytes to Fas-mediated apoptosis34,35 by perturbing cell-surface expression of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor cMet, a competitive inhibitor of Fas-Fas ligand (FasL) interactions.35,36 Furthermore, fat-laden hepatocytes themselves express high levels of FasL,35 creating an environment favoring hepatocellular suicide. The importance of Fas in the pathogenesis of murine NASH was recently demonstrated using a cMet peptide as a synthetic inhibitor of Fas-FasL interactions. This peptide reduced cell death and hepatic inflammation in both leptin-deficient and MCD-fed mice, and in MCD mice it even inhibited hepatic fibrosis.35 These results point to cell death as a pivotal stimulus to NASH, echoing similar observations in other liver diseases such as viral hepatitis and obstructive cholestasis.37,38

TLRs, which are present on all resident cells in the liver,39-43 act as innate immune sensors of foreign or abnormal structures. Select pattern recognition receptors figure prominently in the pathogenesis of NASH because of their potential for activation by saturated fatty acids19 and because of their interaction with bacterial products such as Gram-negative endotoxin, which is found in the circulation of animals with obesity and fatty liver.44,45 High-fat and MCD feeding induce hepatic expression of TLR2 and TLR4 as well as the TLR4 coreceptors CD14 and MD2.21, 45 Steatosis also sensitizes the liver to challenge by TLR4 ligands.45-47 Signaling through these receptors can promote NASH by inducing hepatic expression of a host of proinflammatory mediators.43 In human beings, NAFLD has been associated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, although not necessarily through bacterial interactions with TLRs.48 Likewise, the intestinal microbiome has recently been reported to play a central role in the development of obesity and fatty liver disease, not because of effects on innate immunity but instead because of direct effects on nutrient and energy metabolism.49,50 Even so, probiotics, which reportedly suppress TLR-related responses by altering intestinal flora,51,52 improve liver injury and inflammation in animals and humans with fatty livers,53,54 and dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are known inhibitors of TLR signaling,55 suppress necroinflammation and fibrosis in experimental fatty liver disease.56 The therapeutic success of these molecules suggests that the composition of the intestinal flora can influence innate immune processes leading to NAFLD.

Innate immune responses activated within fatty livers have great potential for amplification through cellular and humoral cross-talk. For example, hepatocyte apoptosis stimulates chemokine production57 and induces Kupffer cells to produce FasL and cytokines,58 which can augment cell death and promote hepatic inflammation. Hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and possibly other resident liver cells can also be stimulated to produce cytokines and chemokines through intracellular activation of IKK and JNK (see above) or extracellular activation of TLRs.20,21,31,45 These compounds can then act in an autocrine or paracrine fashion to induce cell death, stimulate production of reactive oxygen species and recruit leukocytes from the circulation. A number of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (TNF_α_, interleukin-1 [IL-1], IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-18, TNF, and macrophage inflammatory pro-tein-2) are up-regulated in fatty livers.21,23,26,44,59-63 TNF_α_ has been extensively studied as a putative mediator of NASH, albeit with mixed results.31,53,59,64-66 More recently, attention has turned to the overall profile of proinflammatory cytokines in fatty livers, which is typical of that seen in T helper-1 (Th1) lymphocyte responses. Although NASH is not classically considered a Th1-polar-ized disease, data from several recent reports suggest that an imbalance resulting from a relative excess in proinflammatory Th1 cytokines such as interferon-γ and a relative deficiency of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10 can influence fatty liver disease.60,67 Natural killer T (NKT) cells are regulatory T lymphocytes that are activated by specific glycolipids presented by the major histocompatibility class I–like molecule CD1d. T cells are typically considered components of adaptive immunity, but NKT cells are preactivated in situ by endogenous (self) glycolipids and are considered to be innate immune effectors.68 They likely play a role in the innate or intrinsic propensity of an individual to mount either Th1 or Th2 cytokine responses. Th2-skewed IL-4–producing NKT cells are diminished in number in mice with leptin-defi-ciency60 or diet-induced obesity.61 The severity of liver injury in these animals is inversely proportional to NKT cell number. The reason for this reduction appears multifactorial, involving activation-induced death of NKT cells in response to Kupffer cell– derived IL-1261 as well as decreased NKT survival due to reduced exposure to CD1d on the hepatocyte surface.69 Notably, adoptive transfer of IL-4–producing NKT cells results in amelioration of steatosis and diminished hepatic levels of the Th1-like cytokine IL-12 in Kupffer cells.67,70 These experiments suggest that NKT cell– derived cytokines such as IL-4 play a protective role in diet-induced NAFLD, and they intimate that polarized Th1 cytokines play pathophysiologic roles in fat-induced inflammation and steatosis.

Inflammatory Signals in Adipose Tissue and Their Relation to NAFLD

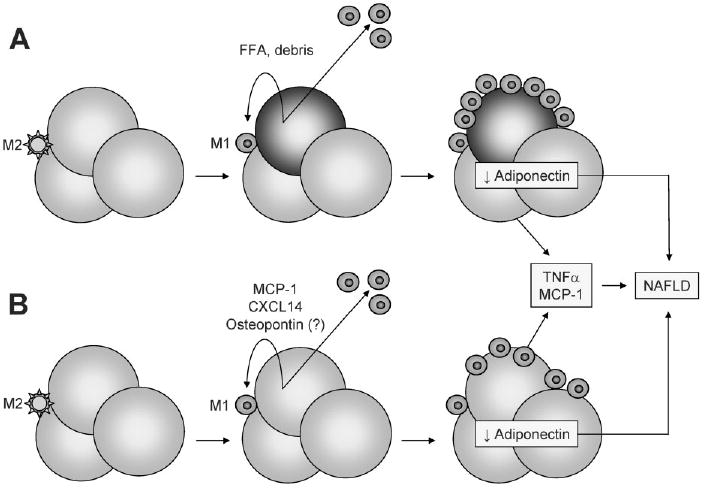

Although the metabolic syndromes of atherosclerosis and NAFLD are clearly associated with organ-specific inflammation, the discovery that adipose tissue itself is inflamed in obesity was not made until 2003.71 At that time, macrophages were identified as the principal effectors of adipose tissue inflammation, based on microarray studies showing that obese mice exhibit markedly increased expression of macrophage-specific genes in white adipose tissue, combined with immunohistochemical studies demonstrating significant and selective infiltration of the adipose tissue by macrophages.72-74 This breakthrough is relevant to NAFLD, because emerging data suggest that the inflammatory state of adipose tissue controls lipid homeostasis in other organs, including the liver.3,4,75 The mechanisms by which obesity causes macrophages to infiltrate adipose tissue are currently unknown. Some suggest that excessive lipid loading causes adipocytes to undergo necrosis, which activates resident macrophages and promotes macrophage recruitment from the circulation (Fig. 2A).76 Others argue that obesity activates macrophages in the circulation77 and that these cells are then recruited to adipose tissue by an obesity-related signal emanating from adipocytes (Fig. 2B). In this regard, high-fat feeding induces adipocytes to express the chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), whose binding partner is C-C chemokine receptor-2 (CCR2).3,4 Adipocyte-derived MCP-1 stimulates the recruitment of CCR2-expressing macrophages into adipose tissue.3,4 Importantly, it also causes hepatic insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis, and even affects behavior, enhancing food intake. Conversely, mice deficient in either MCP-1 or CCR2 do not exhibit macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue and are protected from diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance.3,4 Blockade of the MCP-1/CCR2 axis reduces, but does not eliminate, high-fat diet–induced infiltration of macrophages into adipose tissue, raising the possibility that other inflammatory and chemotactic agents also contribute to this process. One candidate is C-X-C chemokine ligand-14 (CXCL14), which is selectively induced in adipose tissue of obese mice.78,79 Like MCP-1–deficient mice, CXCL14-defi-cient mice exhibit diminished adipose tissue macrophage recruitment, improved insulin responsiveness, and reduced liver weight in comparison to wild-type mice in response to high-fat feeding.78 Macrophage recruitment to adipose tissue may also involve the proinflammatory cytokine osteopontin.80 Evidence for this comes from osteopontin-deficient mice, which exhibit impaired macrophage recruitment into adipose tissue upon high-fat feeding as well as attenuated systemic inflammation and improved insulin resistance.81

Fig. 2.

Proposed mechanisms of adipose tissue macrophage activation and their contribution to NAFLD. (A) Normal adipose tissue contains a small number of resident macrophages with an M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotype. Expansion of adipocytes with fat in obesity can provoke adipocyte necrosis, with the released cellular debris and free fatty acids (FFA) activating resident macrophages and signaling the recruitment of M1 (proinflammatory) macrophages from the circulation. The resulting inflamed fat produces high levels of TNF_α_ and MCP-1 and low levels of adiponectin, which can contribute to NAFLD. TNF_α_ and MCP-1 can derive from both adipocytes and macrophages, whereas adiponectin is produced exclusively by adipocytes. (B) Obese adipocytes remain viable but are induced to secrete MCP-1, CXCL14, and perhaps osteopontin. This attracts and activates macrophages to an M1 phenotype. The end result is the same, with inflamed fat producing high levels of TNF_α_ and MCP-1 and low levels of adiponectin.

Additional studies demonstrate that obesity affects not only macrophage recruitment to, but also macrophage phenotype within, adipose tissue. Plasticity and functional polarization are characteristics of macrophages; these cells can be induced to express features typical of either inflammatory or noninflammatory (resident) macrophages, depending on their exposure to divergent stimuli. Macrophage phenotype has been defined across at least two separate polarization states, termed M1 and M2.82 M1 or “classically activated” macrophages are induced by proinflammatory mediators such as lipopolysaccharide and interferon-γ. They are characterized by a high capacity to present antigen, robust IL-12, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-23 production,83 and consequent activation of polarized Th1 responses. M1 macrophages also produce reactive oxygen species such as nitric oxide (NO) via activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). The term M2 or “alternatively activated” macrophages has been applied to macrophages generated in response to IL-4 and IL-13, which can promote Th2 responses.82 These cells have low proinflammatory cytokine expression, and instead express high levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 and the IL-1 decoy receptor. Another property of M2 macrophages is that they have elevated levels of arginase, which competes with iNOS for the substrate L-arginine. Whereas iNOS utilizes L-arginine to generate reactive NO species with microbicidal and proinflammatory M1 effects, arginase hydrolyzes arginine and promotes anti-inflammatory M2 effects.84, 85 Recently published data revealed that adipose tissue macrophages from lean mice express many genes characteristic of M2 or “alternatively activated” cells, whereas macrophages from mice with diet-induced obesity express fewer M2 genes and more genes such as TNF_α_ and iNOS, which are characteristic of the M1 phenotype.86

A further link between M1 polarization of macrophages and NAFLD comes from studies of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR_γ_). PPAR_γ_, a genetic sensor of unsaturated fatty acids, serves as a ligand for the RXR nuclear receptor where it classically regulates processes related to fatty acid and glucose metabolism. In addition, PPAR_γ_ has a profound influence on inflammatory responses in macrophages. PPAR_γ_ agonists inhibit macrophage cytokine production by antagonizing the activity of the proinflammatory transcription factors AP-1, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), and NF-κ_B.87, 88 One recent report indicated that PPAR_γ is also required for the complete polarization of macrophages toward the noninflammatory, reparative M2 phenotype.89 Moreover, pharmacologic PPAR_γ_ agonists are able to convert inflammatory M1 macrophages to “alternatively activated” noninflammatory M2 macrophages.90 Together these data indicate that PPAR_γ_ agonists play a key role in the regulation of macrophage phenotype and function. In the context of NASH, this information offers a potentially unique explanation for the therapeutic benefit of PPAR_y_ agonists (thiazolidinediones).91-93 It suggests that the immunomodulatory capabilities of these agents are paramount to their efficacy in controlling the inflammatory and perhaps even the metabolic abnormalities that accompany NASH. In support of this theory, mice lacking PPAR_γ_ in macrophages exhibit enhanced activation of inflammatory signals in the liver at baseline and develop pronounced hepatic insulin resistance in response to high-fat feeding.94 Moreover, patients with insulin resistance who are treated with rosiglitazone show reduced parameters of inflammation even before they exhibit any improvement in insulin sensitivity.95 Also pertinent is that IL-4, a Th2 cytokine produced by NKT cells, is a potent inducer of endogenous PPAR_γ_ ligands.96 This raises the intriguing possibility that in the liver, NKT cells suppress the Th1/M1 environment characteristic of NAFLD through IL-4–mediated production of anti-inflammatory PPAR_γ_ agonists.

When viewed in aggregate, these new and compelling findings suggest that obesity-associated steatohepatitis may be more closely linked to adipose tissue macrophage activation than to the metabolic effects of excess fat stores. Indeed, obesity-induced NAFLD goes hand in hand with adipose tissue macrophage activation, but not always with adiposity, as shown in MCP-1–deficient or CCR2-defi-cient mice that are protected from diet-induced hepatic steatosis even though they still become obese. Collectively, these studies support a paradigm in which adipose tissue macrophages play a major role in the systemic metabolic syndromes of insulin resistance and NAFLD. For the moment, the exact role of adipose tissue macrophages in the pathogenesis of NASH remains uncertain, because investigators focusing on inflammatory adipose tissue have not uniformly extended their work to include a careful examination of liver injury or inflammation. Still, the available data indicate that M1-polarized inflammatory adipose tissue macrophages are central to the development of obesity-associated hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance.3,4 Macrophage infiltration of adipose tissue promotes hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance even in the absence of any evidence of simultaneous macrophage influx into the liver.3,73 This suggests that at least some features of NAFLD, and perhaps even NASH, arise through endocrine interactions with fat. It is possible that classically activated M1 macrophages or inflamed adipocytes secrete a systemic inflammatory mediator that triggers inflammation at remote sites. Some have touted TNF_α_ as such a factor, given its landmark association with insulin resistance,97 but it is noteworthy that TNF receptor 1–deficient mice can still develop diet-induced NASH.31,59 Alternatively, adipose tissue-derived MCP-1 itself, which circulates at high levels in obese animals, could serve as an endocrine mediator of NAFLD through an indirect mechanism, because hepatocytes are not known to express CCR2. It is also possible that instead of stimulating the synthesis of a proinflammatory factor, inflamed macrophages within adipose tissue inhibit the elaboration of a systemic anti-inflammatory mediator from adipocytes. A leading candidate molecule is adiponectin, which is normally secreted by lean, but not obese, adipose tissue.98,99 Adiponectin appears to have anti-inflammatory properties and is sharply lowered in the serum of obese mice. Intriguingly, adiponectin is present in high levels in obese CCR2-deficient mice, which have neither inflamed adipose tissue nor hepatic steatosis.4 The importance of adiponectin to the development of diet-induced metabolic changes was highlighted by a recent study in which leptin-deficient obese mice were genetically engineered to produce high levels of adiponectin.75 Adiponectin overexpression resulted in a reduction in adipose tissue macrophage infiltration and a reduction of circulating IL-6 and TNF_α_, despite a massive expansion of adipose tissue fat. In addition, adipose tissue macrophages from obese adiponectin transgenic mice possessed an alternatively activated M2 phenotype, rather than the typical obesity-induced M1 macrophage phenotype. These data underscore the powerful anti-inflammatory function of adiponectin, which may underlie its protective effects against hepatic steatosis.100 Yet another means by which adipose tissue could contribute to an inflammatory phenotype in liver is for macrophages to become activated within fat and then traffic to the liver, triggering inflammation. Although there are no data to support this notion, peripheral blood macrophages in obese mice appear to be skewed toward the M1 phenotype,77 and resident liver macrophages (Kupffer cells) have an inflammatory phenotype with a predominant expression of the M1 cytokines TNF_α_ and IL-12.60,61

Conclusion

As research into the pathophysiology of NAFLD expands, it is becoming clear that the disease involves a number of innate immune processes both within and outside the liver. It is also becoming evident that steatosis and inflammation actively influence each other by multiple mechanisms, even across organs, as shown in the case of inflamed adipose tissue affecting the metabolic status of the liver. These findings support a theme already common among those who research the metabolic syndrome—that the distinction between metabolism and inflammation has blurred.1,15,71,101 Hotamisligil1 recently noted that the close interconnection between metabolism and inflammation creates a “chicken and egg” dilemma in which it is difficult to tell which process (nutrient excess or inflammation) actually initiates the metabolic syndrome. The available data support a model in which lipids are the primary stimulus to innate immune activation, with the resulting inflammatory milieu then causing metabolic dysregulation (insulin resistance and further fat deposition) and setting into motion a vicious cycle that culminates in end-organ dysfunction.

With regard to innate immunity in NAFLD, yet to be reconciled is whether fatty liver disease is an organ-autonomous process or absolutely requires a contribution from inflamed adipose tissue. Although some studies suggest that features of NAFLD are inducible by events occurring solely within the liver,9,20 others clearly show that inflamed fat worsens these abnormalities.3,4 Still others argue that NASH occurs in patients with lipodystrophy, who have no adipose tissue and thus no adipose tissue inflammation.102 Although the last observation would seem to support a liver-autonomous view of NAFLD pathogenesis, it is important to recall that normal adipose tissue produces adiponectin and other adipokines whose functions are to promote lipid homeostasis and suppress inflammation.103 Metabolic and immune interplay between liver and adipose tissue, therefore, is likely operative in both health and disease, and both organs must be taken into consideration to obtain a complete and accurate picture of NASH pathogenesis.

From a translational perspective, research on innate immune activation in NAFLD has led to several diagnostic and therapeutic advances. For example, high serum levels of MCP-1 and low serum levels of adiponectin are being exploited as markers of disease severity.93,104,105 Similarly, hepatocyte apoptosis in fatty livers, much of which is likely Fas-mediated, forms the basis for using cytokeratin-18 as an independent serum marker of NAFLD.106,107 One rationale for using fish oil to prevent or treat NASH comes from scientific evidence that n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress proinflammatory signaling through TLRs.108 Furthermore, the anti-inflammatory properties of PPAR_γ_ agonists offer an explanation for their efficacy in NASH in spite of persistent adiposity.109 As understanding of the complex relationship between metabolism and inflammation grows, there will undoubtedly be more opportunities to apply knowledge of innate immunity to the management and ultimately the prevention of fatty liver disease.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK061510, R01 DK068450, and P30 DK026743 (UCSF Liver Center).

Abbreviations

CCR2

C-C chemokine receptor-2

ER

endoplasmic reticulum

IKK

inhibitor of NF-κB kinase

IL

interleukin

iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

IRS

insulin receptor substrate

JNK

Jun N-terminal kinase

MCD

methionine-choline-deficient

MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1

NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

NKT

natural killer T cell

PKC

protein kinase C

PPARγ

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ

TLR

Toll-like receptor

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrell GC, Larter CZ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006;43:S99–S112. doi: 10.1002/hep.20973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K, Kitazawa R, et al. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1494–1505. doi: 10.1172/JCI26498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisberg SP, Hunter D, Huber R, Lemieux J, Slaymaker S, Vaddi K, et al. CCR2 modulates inflammatory and metabolic effects of high-fat feeding. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:115–124. doi: 10.1172/JCI24335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao Z, Zhang X, Zuberi A, Hwang D, Quon MJ, Lefevre M, et al. Inhibition of insulin sensitivity by free fatty acids requires activation of multiple serine kinases in 3T3–L1 adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2024–2034. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JK, Fillmore JJ, Sunshine MJ, Albrecht B, Higashimori T, Kim DW, et al. PKC-theta knockout mice are protected from fat-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:823–827. doi: 10.1172/JCI22230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu C, Chen Y, Cline GW, Zhang D, Zong H, Wang Y, et al. Mechanism by which fatty acids inhibit insulin activation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in muscle. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50230–50236. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam TK, Yoshii H, Haber CA, Bogdanovic E, Lam L, Fantus IG, et al. Free fatty acid-induced hepatic insulin resistance: a potential role for protein kinase C-delta. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E682–E691. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00038.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Qu X, Elder BD, Bilz S, Befroy D, et al. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32345–32353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Wang A, Beddow SA, Geisler JG, Kahn M, et al. Inhibition of protein kinase Cepsilon prevents hepatic insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:739–745. doi: 10.1172/JCI30400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solinas G, Naugler W, Galimi F, Lee MS, Karin M. Saturated fatty acids inhibit induction of insulin gene transcription by JNK-mediated phosphorylation of insulin-receptor substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16454–16459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607626103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malhi H, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Gores GJ. Free fatty acids induce JNK-dependent hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12093–12101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hotamisligil GS. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathways in inflammation and origin of obesity and diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(Suppl 2):S73–S78. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.s73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perseghin G, Petersen K, Shulman GI. Cellular mechanism of insulin resistance: potential links with inflammation. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(Suppl 3):S6–S11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1793–1801. doi: 10.1172/JCI29069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozcan U, Cao Q, Yilmaz E, Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Ozdelen E, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2004;306:457–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozcan U, Yilmaz E, Ozcan L, Furuhashi M, Vaillancourt E, Smith RO, et al. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science. 2006;313:1137–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1128294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Czaja MJ. Cell signaling in oxidative stress-induced liver injury. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:378–389. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JY, Hwang DH. The modulation of inflammatory gene expression by lipids: mediation through Toll-like receptors. Mol Cell. 2006;21:174–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arkan MC, Hevener AL, Greten FR, Maeda S, Li ZW, Long JM, et al. IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2005;11:191–198. doi: 10.1038/nm1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai D, Yuan M, Frantz DF, Melendez PA, Hansen L, Lee J, et al. Local and systemic insulin resistance resulting from hepatic activation of IKK-beta and NF-kappaB. Nat Med. 2005;11:183–190. doi: 10.1038/nm1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JK, Kim YJ, Fillmore JJ, Chen Y, Moore I, Lee J, et al. Prevention of fat-induced insulin resistance by salicylate. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:437–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI11559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joshi-Barve S, Barve SS, Amancherla K, Gobejishvili L, Hill D, Cave M, et al. Palmitic acid induces production of proinflammatory cytokine in-terleukin-8 from hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2007;46:823–830. doi: 10.1002/hep.21752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang D, Wei Y, Pagliassotti MJ. Saturated fatty acids promote endoplasmic reticulum stress and liver injury in rats with hepatic steatosis. Endocrinology. 2006;147:943–951. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirosumi J, Tuncman G, Chang L, Gorgun CZ, Uysal KT, Maeda K, et al. A central role for JNK in obesity and insulin resistance. Nature. 2002;420:333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldstein AE, Canbay A, Angulo P, Taniai M, Burgart LJ, Lindor KD, et al. Hepatocyte apoptosis and fas expression are prominent features of human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:437–443. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00907-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schattenberg JM, Singh R, Wang Y, Lefkowitch JH, Rigoli RM, Scherer PE, et al. JNK1 but not JNK2 promotes the development of steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology. 2006;43:163–172. doi: 10.1002/hep.20999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ueki K, Kondo T, Tseng YH, Kahn CR. Central role of suppressors of cytokine signaling proteins in hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10422–10427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402511101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuncman G, Hirosumi J, Solinas G, Chang L, Karin M, Hotamisligil GS. Functional in vivo interactions between JNK1 and JNK2 isoforms in obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10741–10746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603509103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taniguchi CM, Ueki K, Kahn R. Complementary roles of IRS-1 and IRS-2 in the hepatic regulation of metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:718–727. doi: 10.1172/JCI23187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Dela Pena A, Leclercq I, Field J, George J, Jones B, Farrell G. NF-kappaB activation, rather than TNF, mediates hepatic inflammation in a murine dietary model of steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1663–1674. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pagliassotti MJ, Wei Y, Wang D. Insulin protects liver cells from saturated fatty acid-induced apoptosis via inhibition of c-Jun NH2 terminal kinase activity. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3338–3345. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ribeiro PS, Cortez-Pinto H, Sola S, Castro RE, Ramalho RM, Baptista A, et al. Hepatocyte apoptosis, expression of death receptors, and activation of NF-kappaB in the liver of nonalcoholic and alcoholic steatohepatitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1708–1717. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feldstein AE, Canbay A, Guicciardi ME, Higuchi H, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. Diet associated hepatic steatosis sensitizes to Fas mediated liver injury in mice. J Hepatol. 2003;39:978–983. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou C, Ma J, Wang X, Guo L, Zhu Z, Stoops J, et al. Lack of Fas antagonism by Met in human fatty liver disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:1078–1085. doi: 10.1038/nm1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, DeFrances MC, Dai Y, Pediaditakis P, Johnson C, Bell A, et al. A mechanism of cell survival: sequestration of Fas by the HGF receptor Met. Mol Cell. 2002;9:411–421. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canbay A, Feldstein A, Baskin-Bey E, Bronk SF, Gores GJ. The caspase inhibitor IDN-6556 attenuates hepatic injury and fibrosis in the bile duct ligated mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:1191–1196. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.060129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh MJ, Vanags DM, Clouston AD, Richardson MM, Purdie DM, Jonsson JR, et al. Steatosis and liver cell apoptosis in chronic hepatitis C: a mechanism for increased liver injury. Hepatology. 2004;39:1230–1238. doi: 10.1002/hep.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen XM, Splinter PL, O'Hara SP, LaRusso NF. A cellular micro-RNA, let-7i, regulates Toll-like receptor 4 expression and contributes to cholangiocyte immune responses against Cryptosporidium parvum infection. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28929–28938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702633200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu S, Salyapongse AN, Geller DA, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR. Hepatocyte toll-like receptor 2 expression in vivo and in vitro: role of cytokines in induction of rat TLR2 gene expression by lipopolysaccharide. Shock. 2000;14:361–365. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014030-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paik YH, Schwabe RF, Bataller R, Russo MP, Jobin C, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2003;37:1043–1055. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szabo G, Mandrekar P, Dolganiuc A. Innate immune response and hepatic inflammation. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:339–350. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-991511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brun P, Castagliuolo I, Di Leo V, Buda A, Pinzani M, Palu G, et al. Increased intestinal permeability in obese mice: new evidence in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G518–G525. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00024.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rivera CA, Adegboyega P, van Rooijen N, Tagalicud A, Allman M, Wallace M. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling and Kupffer cells play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2007;47:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szabo G, Velayudham A, Romics L, Jr, Mandrekar P. Modulation of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by pattern recognition receptors in mice: the role of toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:140S–145S. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000189287.83544.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Lane MD, Clemens M, Diehl AM. Obesity increases sensitivity to endotoxin liver injury: implications for the pathogenesis of steatohepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2557–2562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wigg AJ, Roberts-Thomson IC, Dymock RB, McCarthy PJ, Grose RH, Cummins AG. The role of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, intestinal permeability, endotoxaemia, and tumour necrosis factor alpha in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Gut. 2001;48:206–211. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Backhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:979–984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605374104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dumas ME, Barton RH, Toye A, Cloarec O, Blancher C, Rothwell A, et al. Metabolic profiling reveals a contribution of gut microbiota to fatty liver phenotype in insulin-resistant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12511–12516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601056103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grabig A, Paclik D, Guzy C, Dankof A, Baumgart DC, Erckenbrecht J, et al. Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917 ameliorates experimental colitis via toll-like receptor 2- and toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathways. Infect Immun. 2006;74:4075–4082. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01449-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rachmilewitz D, Katakura K, Karmeli F, Hayashi T, Reinus C, Rudensky B, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 signaling mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of probiotics in murine experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:520–528. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li Z, Yang S, Lin H, Huang J, Watkins PA, Moser AB, et al. Probiotics and antibodies to TNF inhibit inflammatory activity and improve nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37:343–350. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loguercio C, Federico A, Tuccillo C, Terracciano F, D'Auria MV, De Simone C, et al. Beneficial effects of a probiotic VSL#3 on parameters of liver dysfunction in chronic liver diseases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:540–543. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000165671.25272.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee JY, Zhao L, Youn HS, Weatherill AR, Tapping R, Feng L, et al. Saturated fatty acid activates but polyunsaturated fatty acid inhibits Tolllike receptor 2 dimerized with Toll-like receptor 6 or 1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16971–16979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312990200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Svegliati-Baroni G, Candelaresi C, Saccomanno S, Ferretti G, Bachetti T, Marzioni M, et al. A model of insulin resistance and nonalcoholic steato-hepatitis in rats: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid treatment on liver injury. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:846–860. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Faouzi S, Burckhardt BE, Hanson JC, Campe CB, Schrum LW, Rippe RA, et al. Anti-Fas induces hepatic chemokines and promotes inflammation by an NF-kappa B-independent, caspase-3-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:49077–49082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canbay A, Feldstein AE, Higuchi H, Werneburg N, Grambihler A, Bronk SF, et al. Kupffer cell engulfment of apoptotic bodies stimulates death ligand and cytokine expression. Hepatology. 2003;38:1188–1198. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deng QG, She H, Cheng JH, French SW, Koop DR, Xiong S, et al. Steatohepatitis induced by intragastric overfeeding in mice. Hepatology. 2005;42:905–914. doi: 10.1002/hep.20877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guebre-Xabier M, Yang S, Lin HZ, Schwenk R, Krzych U, Diehl AM. Altered hepatic lymphocyte subpopulations in obesity-related murine fatty livers: potential mechanism for sensitization to liver damage. Hepatology. 2000;31:633–640. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li Z, Soloski MJ, Diehl AM. Dietary factors alter hepatic innate immune system in mice with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42:880–885. doi: 10.1002/hep.20826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu J, Ip E, Dela Pena A, Hou JY, Sesha J, Pera N, et al. COX-2 induction in mice with experimental nutritional steatohepatitis: Role as pro-inflammatory mediator. Hepatology. 2006;43:826–836. doi: 10.1002/hep.21108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomita K, Tamiya G, Ando S, Ohsumi K, Chiyo T, Mizutani A, et al. Tumour necrosis factor alpha signalling through activation of Kupffer cells plays an essential role in liver fibrosis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Gut. 2006;55:415–424. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.071118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garcia-Ruiz I, Rodriguez-Juan C, Diaz-Sanjuan T, del Hoyo P, Colina F, Munoz-Yague T, et al. Uric acid and anti-TNF antibody improve mitochondrial dysfunction in ob/ob mice. Hepatology. 2006;44:581–591. doi: 10.1002/hep.21313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koppe SW, Sahai A, Malladi P, Whitington PF, Green RM. Pentoxifyl-line attenuates steatohepatitis induced by the methionine choline deficient diet. J Hepatol. 2004;41:592–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Memon RA, Grunfeld C, Feingold KR. TNF-alpha is not the cause of fatty liver disease in obese diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2001;7:2–3. doi: 10.1038/83316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elinav E, Pappo O, Sklair-Levy M, Margalit M, Shibolet O, Gomori M, et al. Amelioration of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and glucose intolerance in ob/ob mice by oral immune regulation towards liver-extracted proteins is associated with elevated intrahepatic NKT lymphocytes and serum IL-10 levels. J Pathol. 2006;208:74–81. doi: 10.1002/path.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang L, Jhaveri R, Huang J, Qi Y, Diehl AM. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, hepatocyte CD1d and NKT cell abnormalities in murine fatty livers. Lab Invest. 2007;87:927–937. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elinav E, Pappo O, Sklair-Levy M, Margalit M, Shibolet O, Gomori M, et al. Adoptive transfer of regulatory NKT lymphocytes ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and glucose intolerance in ob/ob mice and is associated with intrahepatic CD8 trapping. J Pathol. 2006;209:121–128. doi: 10.1002/path.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1785–1788. doi: 10.1172/JCI20514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takahashi K, Mizuarai S, Araki H, Mashiko S, Ishihara A, Kanatani A, et al. Adiposity elevates plasma MCP-1 levels leading to the increased CD11b-positive monocytes in mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46654–46660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim JY, van de Wall E, Laplante M, Azzara A, Trujillo ME, Hofmann SM, et al. Obesity-associated improvements in metabolic profile through expansion of adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2621–2637. doi: 10.1172/JCI31021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cinti S, Mitchell G, Barbatelli G, Murano I, Ceresi E, Faloia E, et al. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2347–2355. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500294-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghanim H, Aljada A, Hofmeyer D, Syed T, Mohanty P, Dandona P. Circulating mononuclear cells in the obese are in a proinflammatory state. Circulation. 2004;110:1564–1571. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142055.53122.FA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nara N, Nakayama Y, Okamoto S, Tamura H, Kiyono M, Muraoka M, et al. Disruption of CXC motif chemokine ligand-14 in mice ameliorates obesity-induced insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:30794–30803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700412200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takahashi M, Takahashi Y, Takahashi K, Zolotaryov FN, Hong KS, Iida K, et al. CXCL14 enhances insulin-dependent glucose uptake in adipo-cytes and is related to high-fat diet-induced obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;364:1037–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Giachelli CM, Lombardi D, Johnson RJ, Murry CE, Almeida M. Evidence for a role of osteopontin in macrophage infiltration in response to pathological stimuli in vivo. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:353–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nomiyama T, Perez-Tilve D, Ogawa D, Gizard F, Zhao Y, Heywood EB, et al. Osteopontin mediates obesity-induced adipose tissue macrophage infiltration and insulin resistance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2877–2888. doi: 10.1172/JCI31986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Verreck FA, de Boer T, Langenberg DM, Hoeve MA, Kramer M, Vais-berg E, et al. Human IL-23-producing type 1 macrophages promote but IL-10-producing type 2 macrophages subvert immunity to (myco)bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4560–4565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400983101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gordon S. Macrophage heterogeneity and tissue lipids. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:89–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI30992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mosser DM. The many faces of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:209–212. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0602325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:175–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI29881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pascual G, Fong AL, Ogawa S, Gamliel A, Li AC, Perissi V, et al. A SUMOylation-dependent pathway mediates transrepression of inflammatory response genes by PPAR-gamma. Nature. 2005;437:759–763. doi: 10.1038/nature03988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, Kelly CJ, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macro-phage activation. Nature. 1998;391:79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Odegaard JI, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Goforth MH, Morel CR, Subramanian V, Mukundan L, et al. Macrophage-specific PPARgamma controls alternative activation and improves insulin resistance. Nature. 2007;447:1116–1120. doi: 10.1038/nature05894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bouhlel MA, Derudas B, Rigamonti E, Dievart R, Brozek J, Haulon S, et al. PPARgamma activation primes human monocytes into alternative M2 macrophages with anti-inflammatory properties. Cell Metab. 2007;6:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Belfort R, Harrison SA, Brown K, Darland C, Finch J, Hardies J, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of pioglitazone in subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2297–2307. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Brunt EM, Wehmeier KR, Oliver D, Bacon BR. Improved nonalcoholic steatohepatitis after 48 weeks of treatment with the PPAR-gamma ligand rosiglitazone. Hepatology. 2003;38:1008–1017. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Promrat K, Lutchman G, Uwaifo GI, Freedman RJ, Soza A, Heller T, et al. A pilot study of pioglitazone treatment for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2004;39:188–196. doi: 10.1002/hep.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hevener AL, Olefsky JM, Reichart D, Nguyen MT, Bandyopadyhay G, Leung HY, et al. Macrophage PPAR gamma is required for normal skeletal muscle and hepatic insulin sensitivity and full antidiabetic effects of thiazolidinediones. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1658–1669. doi: 10.1172/JCI31561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ghanim H, Dhindsa S, Aljada A, Chaudhuri A, Viswanathan P, Dan-dona P. Low-dose rosiglitazone exerts an antiinflammatory effect with an increase in adiponectin independently of free fatty acid fall and insulin sensitization in obese type 2 diabetics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3553–3558. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huang JT, Welch JS, Ricote M, Binder CJ, Willson TM, Kelly C, et al. Interleukin-4-dependent production of PPAR-gamma ligands in macro-phages by 12/15-lipoxygenase. Nature. 1999;400:378–382. doi: 10.1038/22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM. Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2409–2415. doi: 10.1172/JCI117936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hu E, Liang P, Spiegelman BM. AdipoQ is a novel adipose-specific gene dysregulated in obesity. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10697–10703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.18.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Terauchi Y, Kubota N, Hara K, et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7:941–946. doi: 10.1038/90984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.You M, Considine RV, Leone TC, Kelly DP, Crabb DW. Role of adiponectin in the protective action of dietary saturated fat against alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Hepatology. 2005;42:568–577. doi: 10.1002/hep.20821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Neels JG, Olefsky JM. Inflamed fat: what starts the fire? J Clin Invest. 2006;116:33–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI27280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Javor ED, Ghany MG, Cochran EK, Oral EA, DePaoli AM, Premkumar A, et al. Leptin reverses nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with severe lipodystrophy. Hepatology. 2005;41:753–760. doi: 10.1002/hep.20672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Role of adiponectin and PBEF/visfatin as regulators of inflammation: involvement in obesity-associated diseases. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;114:275–288. doi: 10.1042/CS20070196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Haukeland JW, Damas JK, Konopski Z, Loberg EM, Haaland T, Goverud I, et al. Systemic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is characterized by elevated levels of CCL2. J Hepatol. 2006;44:1167–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hui JM, Hodge A, Farrell GC, Kench JG, Kriketos A, George J. Beyond insulin resistance in NASH: TNF-alpha or adiponectin? Hepatology. 2004;40:46–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wieckowska A, Zein NN, Yerian LM, Lopez AR, McCullough AJ, Feld-stein AE. In vivo assessment of liver cell apoptosis as a novel biomarker of disease severity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2006;44:27–33. doi: 10.1002/hep.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yilmaz Y, Dolar E, Ulukaya E, Akgoz S, Keskin M, Kiyici M, et al. Soluble forms of extracellular cytokeratin 18 may differentiate simple steatosis from nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:837–844. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i6.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Capanni M, Calella F, Biagini MR, Genise S, Raimondi L, Bedogni G, et al. Prolonged n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation ameliorates hepatic steatosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1143–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Stienstra R, Duval C, Muller M, Kersten S. PPARs, Obesity, and Inflammation. PPAR Res. 2007;2007:95974. doi: 10.1155/2007/95974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]