Ubiquitin-Regulated Recruitment of IκB Kinase ɛ to the MAVS Interferon Signaling Adapter (original) (raw)

Abstract

Induction of the antiviral interferon response is initiated upon recognition of viral RNA structures by the RIG-I or Mda-5 DEX(D/H) helicases. A complex signaling cascade then converges at the mitochondrial adapter MAVS, culminating in the activation of the IRF and NF-κB transcription factors and the induction of interferon gene expression. We have previously shown that MAVS recruits IκB kinase ɛ (IKKɛ) but not TBK-1 to the mitochondria following viral infection. Here we map the interaction of MAVS and IKKɛ to the C-terminal region of MAVS and demonstrate that this interaction is ubiquitin dependent. MAVS is ubiquitinated following Sendai virus infection, and K63-linked ubiquitination of lysine 500 (K500) of MAVS mediates recruitment of IKKɛ to the mitochondria. Real-time PCR analysis reveals that a K500R mutant of MAVS increases the mRNA level of several interferon-stimulated genes and correlates with increased NF-κB activation. Thus, recruitment of IKKɛ to the mitochondria upon MAVS K500 ubiquitination plays a modulatory role in the cascade leading to NF-κB activation and expression of inflammatory and antiviral genes. These results provide further support for the differential role of IKKɛ and TBK-1 in the RIG-I/Mda5 pathway.

Recognition of viral RNA ligands by the cytoplasmic DEX(D/H) helicase RIG-I (RNA helicase retinoic acid-inducible gene I) receptors and Mda5 (melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5) results in the induction of type I (alpha/beta) interferons (IFN-α/β) and establishment of an antiviral state (18-20, 50, 53, 59). The mitochondrial adapter MAVS/IPS-1/Cardif/VISA is directly downstream of the helicases and acts as a pivotal point in the cascade leading to activation of the transcription factors IRF-3 and -7 and NF-κB, which synergistically regulate IFN-β gene expression (21, 30, 45, 49, 58). Secreted IFN-α/β binds to its cognate IFNAR receptor in neighboring cells and initiates a second wave of IFN response, mediated by a complex known as ISGF3, which is composed of STAT-1, STAT-2, and IRF-9 transcription factors (27, 39, 54). During the second wave, IFN production is amplified with the expression of multiple IFN-α subtypes and hundreds of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), including recently identified IκB kinase ɛ (IKKɛ)-specific genes such as ADAR-1, IFIT3, and OAS1 (51).

The MAVS adapter contains an amino-terminal caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) that interacts with the CARDs of RIG-I/Mda5 and a carboxy-terminal transmembrane (TM) domain that anchors MAVS to the outer mitochondrial membrane (21, 30, 45, 58). The essential role of MAVS in antiviral signaling was demonstrated by the failure of MAVS-deficient mice to mount a proper IFN response to poly(I·C) stimulation and by their severely compromised immune defense against virus infection (24, 49). Interestingly, MAVS expression alone, in the absence of virus infection, is sufficient to trigger the IRF and NF-κB pathways leading to IFN production. Engagement of MAVS by active RIG-I/Mda5 leads to dimerization (3) and formation of a mitochondrial platform where multiple signaling molecules converge to mediate activation of the classical IKK complex and/or the IKK-related kinases IKKɛ and TBK-1 (12, 21, 30, 31, 42, 43, 45, 58, 60, 61).

TBK-1 and IKKɛ activate the IRF pathway by direct phosphorylation of IRF-3 and IRF-7 in their C-terminal regulatory region (9, 26, 29, 34, 46, 52). Analysis of knockout mice demonstrated that the ubiquitously expressed TBK-1 is the major mediator of IRF-3/-7 phosphorylation and initiator of the antiviral response (15, 35, 38). Disruption of IKKɛ expression on the other hand had a minimal effect on the activation of IRF-3/-7 and was considered dispensable for the induction of the IFN response (15, 35, 38). However, following viral infection IKKɛ, but not TBK-1, phosphorylates STAT-1 on serine 708 and increases expression of genes such as ADAR-1, IFIT3, and OAS1 (51). Importantly, this observation suggests that differences at the level of substrate specificity may exist for the two kinases (28, 51). Mechanistic differences in the activation of TBK-1 and IKKɛ may also be expected, based on differences in cytoplasmic localization of the two kinases as well as the observation that IKKɛ is directly recruited to the mitochondrial network via MAVS following virus infection, whereas TBK-1 remains largely cytoplasmic (16, 23, 25, 30).

In the pathway leading to NF-κB activation, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors 2 and 6 (TRAF2 and -6) bind to specific TRAF interaction motifs within MAVS (45, 58). TRAF6 facilitates K63-linked polyubiquitination of NEMO, whereas TRAF2 does so for RIP-1 (40, 43). K63-linked polyubiquitination of RIP-1 allows interaction between RIP-1 and NEMO, the regulatory subunit of the IKK complex (56). Activation of the IKK complex then leads to phosphorylation of the inhibitory molecule IκBα and release of active p65/p50 NF-κB dimers, which translocate into the nucleus and activate transcription of target genes. TRAF3 is also recruited to MAVS, where it serves an essential role in IRF-3/-7 activation (33, 41, 58). The kinases TBK-1 and IKKɛ can also potentiate activation of the NF-κB pathway by phosphorylating substrates such as p65 and c-Rel (10, 13, 14, 36, 47; reviewed in reference 7).

The MAVS molecule has emerged as the key regulatory platform in RIG-I signaling, and it is involved in the recruitment of adapter complexes that activate IRF-3/-7 and NF-κB. Posttranslational modifications such as ubiquitination and phosphorylation also play an essential role in the regulation of this complex activation cascade: K63-linked ubiquitination of proteins like RIG-I and NEMO promotes protein-protein interaction and pathway activation (8, 11, 43, 55, 57), whereas K48-linked polyubiquitination, as in the case of IRF-3 and RIG-I, leads to proteasomal degradation and shutdown of signaling (2, 4). In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time that MAVS undergoes extensive ubiquitination following viral infection, attaching both K63- and K48-linked polyubiquitin chains; furthermore, lysine 500 (K500) is an acceptor site for K63-linked ubiquitin chains. Ubiquitination at K500 mediates recruitment of IKKɛ to MAVS, and a K500R mutation results in the loss of the IKKɛ-MAVS interaction. Interestingly, IKKɛ recruitment to MAVS results in MAVS phosphorylation and negative regulation of the NF-κB pathway with a concomitant decrease in IFN-β and ISG expression. We therefore propose a novel negative regulatory role for IKKɛ in the MAVS signaling pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction and mutagenesis.

Plasmids encoding Flag-IKKɛ, Flag-TBK-1, Flag-MAVS, Myc-MAVS, Myc-MAVS(1-155), and Myc-MAVS(71-540) have been previously described (25, 46). Myc-MAVS deletion constructs including amino acids (aa) 1 to 507, 1 to 466, 1 to 400, 1 to 350, 1 to 300, 156 to 540, 364 to 540, 468 to 540, and 503 to 540 and Flag-MAVS(Δ101-480) were generated by PCR followed by cloning into pCDNA3.1-Myc or pCDNA3.1-Flag, respectively. MAVS point mutants at K500 and K136 to arginine (R) [Myc-MAVS(K500R), Myc-MAVS 468-540(K500R), Myc-MAVS(K136R), and Flag-MAVS(Δ101-480)-K500R] were generated by site-directed mutagenesis as per the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Hemagglutinin (HA)-ubiquitin wild type (wt) was a kind gift from Sylvain Meloche (IRIC and Department of Pharmacology, Montreal University, Canada), and other HA-ubiquitin constructs (HA-Ubi-K48, HA-Ubi-K63, and HA-Ubi-KO) were kind gifts from Zhijian Chen (Department of Molecular Biology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center).

Tissue culture and virus infection.

A549 cells were cultured in F12K medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. HEK293, Cos-7, and HeLa cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. MAVS wild-type and knockout (KO) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFS; kind gift from Zhijian Chen) were cultured in 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% l-glutamine. Culture media and supplements were purchased from Wisent Inc. (St. Bruno, Canada). Transient transfections were carried out in subconfluent HEK293 cells by using calcium phosphate, Fugene6 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) in HeLa cells, or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) when indicated, as per the manufacturer's recommendations. Where indicated, A549 cells were infected with Sendai virus (SeV) at 40 hemagglutinating units (HAU)/ml (Charles River Laboratories) in serum-free medium supplemented with serum 1 h postinfection. Poly(I·C) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) treatment was performed as previously described (52). Briefly, 2 μg of poly(I·C) was transfected into HEK293 cells by using calcium phosphate and samples were harvested at the indicated times for whole-cell extract (WCE) preparation.

Luciferase assay.

Subconfluent HeLa cells were transfected with 20 ng of pRLnull reporter (Renilla luciferase, internal control), 100 ng of pGL3-IFN-β, pGL3-NF-κB, pGL3-p2(2), or pGL3-RANTES and 50 ng MAVS-Myc (wt or K500R) or (Δ101-480) (wt or K500R) as indicated. For gene knockdown analysis, control and IKKɛ RNA interference sequence targeting IKKɛ was performed as previously described (46, 48). The small interfering RNA (siRNA) was transfected in HeLa cells using Lipofectamine 2000 and allowed to express for at least 48 h. The cells were then subjected to a second round of transfection with the internal control, promoter, and expression construct. At 24 h posttransfection, reporter gene activity was measured by the dual-luciferase reporter assay (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions using a GLIOMAX 20/20 luminometer (Promega Corporation). Three independent experiments were carried out in triplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviations for triplicates.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy.

Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described (25). Briefly, cells were seeded on glass coverslips and staining of mitochondria was achieved in 25 nM MitoTracker Deep Red FM (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 min at 37°C. Excess Mitotracker Deep Red was removed and coverslips were fixed in warm fixing solution (3.7% paraformaldehyde-10% FBS-phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) for 15 min at 37°C. Further steps were carried out at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized for 30 min in 0.2% Triton X-100-3% immunoglobulin G (IgG)-free bovine serum albumin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) in PBS. Coverslips were exposed to primary antibody solutions for 1 h. Anti-MAVS antibody was diluted at 1:200, anti-IKKɛ antibody was used at 1 μg/ml, and anti-TBK-1 antibody was diluted at 1:500; all dilutions were prepared in buffer A (PBS-0.5% IgG-free bovine serum albumin). After washes, the coverslips were incubated for 1 h in fluorochrome-coupled secondary antibody solutions (2 μg/ml, red and/or green, as indicated). Coverslips were washed and mounted on slides using ImmuMount (Thermo Electron Corp., Pittsburgh, PA). Samples were analyzed on an inverted Axiovert 200M Zeiss microscope equipped with an LSM 5-Pa confocal imaging system (Carl Zeiss Canada, Montreal, Canada). Confocal images (0.3- to 0.5-μm slices) were acquired with a Plan-Apochromat 63× oil objective, using the argon and HeNe laser lines (488 and 543 nm, respectively).

Immunoblot analysis.

WCE (30 to 50 μg) were separated in 7.5 to 15% acrylamide gels by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, Canada). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% (vol/vol) dried milk-0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 in PBS and then were probed with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. After washes, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody solutions (1:3,000 in 5% milk-PBS; KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) for 1 h at room temperature, washed, and revealed using an enhanced chemilumenscence (ECL) reagent (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) or ECL Plus (Amersham, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) for phospho-specific antibodies according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with Myc-MAVS expression plasmids. Cells were harvested and immediately lysed in a 1% Triton X-100 lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 40 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM Na3VO4, 5 mM NaF, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM _N_-ethylmaleimide). Immunoprecipitation was carried out in WCE (300 μg) with 1 μg of anti-Myc (9E10; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) coupled to 50 μl of A/G Plus-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4°C with constant agitation. Following five washes with supplemented lysis buffer, samples were denatured in 2% SDS loading dye, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, Canada). Coimmunoprecipitated IKKɛ was detected with an anti-Flag antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

For endogenous protein interactions, A549 cells were infected or not with SeV as described above. At 2, 4, 6, and 8 h postinfection cells were harvested and lysed as described above. Immunoprecipitation was carried out on WCE (1 mg) using an anti-MAVS antibody raised against the N terminal (rabbit polyclonal; in house) for 16 h at 4°C with constant agitation. Following washes, samples were analyzed by immunoblotting. Coimmunoprecipitated IKKɛ was detected using an anti-IKKɛ mouse monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

In vivo ubiquitination assay.

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with Myc-MAVS and HA-ubiquitin expression plasmids. Samples were harvested 24 h posttransfection, and WCE were prepared in a 1% NP-40 lysis buffer (44) supplemented with 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and the deubiquitinase inhibitor _N_-ethylmaleimide (10 mM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Protein-protein interactions were disrupted by sonication (three pulses of 10 s) using the 550 Sonic Dismembrator (Fisher Scientific Inc., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) followed by boiling for 10 min in 1% SDS. WCE (250 to 500 μg) were immunoprecipitated with 1 μg of anti-Flag antibody (M2; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or anti-Myc antibody (9E10; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as described above. Polyubiquitination was detected using a monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

For detection of endogenous ubiquitinated MAVS following viral infection A549 cells were infected with Sendai virus at 40 HAU/ml and harvested for whole-cell extracts. Immunoprecipitation was performed on 1 mg of protein with an anti-MAVS cocktail, as described above. After transfer, the membrane was denatured in a 6 M guanidine-HCl solution (6 M guanidine-HCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mM dithiothreitol) for 30 min at room temperature. The polyubiquitination signal was detected using an antiubiquitin monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

In vitro ubiquitin binding assay.

To investigate IKKɛ's ability to bind K63-polyubiquitin chains, HEK293 cells were transfected with either Flag-IKKɛ or Flag-TBK-1 by the calcium transfection phosphate method. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were harvested, lysed, and immunoprecipitated using an anti-Flag antibody. Samples were boiled in 1% SDS as explained above for the in vivo ubiquitination assay. Following immunoprecipitation of IKKɛ or TBK-1, complexes was incubated with recombinant K63-ubiquitin chains (Ub2-7) (BostonBiochem, Cambridge, MA) using various concentrations (0.5, 1, and 2.5 μg). Detection of K63-ubiquitin chains was performed using an antiubiquitin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

Isolation of pure mitochondria.

Two-step mitochondrial isolation was carried out as follows: A549 cells (2 × 107) infected or not with SeV (4 h; 40 HAU/ml) were harvested and a first isolation was performed using the mitochondria isolation kit of Pierce (Fischer Scientific, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) as per the manufacturer's instructions. The crude mitochondria preparation was further purified by centrifugation in a discontinuous sucrose gradient (1-ml layers of 1.0, 1.3, 1.6, and 2.0 M sucrose in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA) for 2 h at 80,000 × g. The purified mitochondria were recovered from the interface between the 1.0 and 1.3 M sucrose layers. For other mitochondria preparations, a single isolation using the Pierce mitochondria isolation kit was performed.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

DNase-treated total RNA from HeLa cells transfected with Myc-MAVS-wt, Myc-MAVS(K500R), MAVS(Δ101-480), and MAVS(Δ101-480)-K500R was prepared using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Germany). RNA concentration was determined by absorption at 260 nm, and RNA quality was ensured by an _A_260/_A_280 ratio of ≥2.0. Total RNA was reverse transcribed with 100 U of SuperScript II Plus RNase H reverse transcriptase using oligo AnCT primers (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, CA). Quantitative PCRs were performed in triplicate using SYBR green I on a LightCycler apparatus (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The list of primers is included in Table S1 of the supplemental material. PCR efficiency results were obtained from duplicate measurements of two individual cDNA samples. Experiments were performed at least twice. All data are presented as a relative quantification, based on the relative expression of target genes versus that of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the reference gene.

RESULTS

Interaction of MAVS with IKKɛ is ubiquitin dependent.

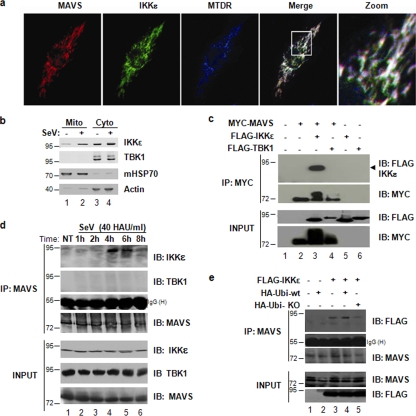

IKKɛ but not TBK-1 was previously demonstrated to colocalize with MAVS following activation of the RIG-I pathway (Fig. 1a) (16, 23, 25, 30). Furthermore, a portion of the IKKɛ cytosolic pool is redistributed to the mitochondrial fraction in response to SeV infection, a phenomenon that is not observed for TBK-1 (Fig. 1b). Coimmunoprecipitation experiments also revealed that Myc-tagged MAVS interacted with Flag-tagged IKKɛ but not TBK-1 (Fig. 1c). Challenge of A549 cells with SeV followed by immunoprecipitation of MAVS and immunoblotting with anti-IKKɛ antibody demonstrated an inducible interaction of the endogenous proteins at 4 to 6 h postinfection (Fig. 1d), confirming the fractionation studies (Fig. 1b). These results strongly indicate that IKKɛ directly interacts with MAVS, whereas TBK-1 may require another adapter molecule for proper spatio-temporal recruitment.

FIG. 1.

MAVS directly recruits IKKɛ to the mitochondria. (a) COS-7 cells were transfected with IKKɛ and MAVS expression plasmids. The mitochondrial network was stained with MitoTracker (blue). Cells were fixed and stained for either MAVS (red) or IKKɛ (green). The confocal images were merged. A zoom of the merge can also be seen. (b) Subcellular localization of IKKɛ and TBK-1 following SeV infection of A549 cells (4 h; 40 HAU/ml). Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-IKKɛ and anti-TBK-1 antibodies. HSP70 was used as a mitochondrial marker, and β-actin was used a cytoplasmic marker. (c) HEK293 cells expressing Myc-MAVS, Flag-IKKɛ, and Flag-TBK-1 expression plasmids were submitted to immunoprecipitation with an anti-Myc antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG antibody (top panel). Equal amounts of immunoprecipitated MAVS were revealed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc (second panel). Inputs for IKKɛ, TBK-1, and MAVS are shown. (d) Endogenous interaction between MAVS and IKKɛ was determined in A549 cells infected with SeV (40 HAU/ml) for the indicated times. Endogenous MAVS was immunoprecipitated using an anti-MAVS antibody cocktail, and interaction with IKKɛ was revealed using an anti-IKKɛ antibody (top panel). Immunoblotting with a TBK-1-specific antibody showed no interaction between MAVS and TBK-1 (second panel). Equal amounts of immunoprecipitated MAVS and IgG heavy chain are shown. Input for IKKɛ, TBK-1, and MAVS are shown (last three panels). (e) The dependence of the MAVS-IKKɛ interaction on ubiquitination was demonstrated in HEK293 cells transfected with plasmids expressing Flag-IKKɛ, HA-ubiquitin, and HA-ubiquitin-KO as indicated. Immunoprecipitation of endogenous MAVS using an anti-MAVS antibody cocktail was followed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag antibody to reveal the interaction with Flag-IKKɛ.

To understand further the interaction between MAVS and IKKɛ, the possibility that ubiquitination may be involved in this process was examined. Indeed, the interaction between MAVS and IKKɛ was dependent on ubiquitination, since the presence of a dominant negative ubiquitin, in which all lysine residues were mutated to arginine and therefore were unable to form polyubiquitin chains (Ubi-KO), reduced interaction between endogenous MAVS and Flag-IKKɛ by 75% (Fig. 1e, compare lanes 3 and 5). Conversely, in the presence of wild-type ubiquitin (HA-Ubi-wt), interaction between MAVS and IKKɛ was increased by approximately 30% (Fig. 1e, compare lanes 3 and 4), suggesting that the interaction between MAVS and IKKɛ was dependent upon the ubiquitination status of one or both proteins. The presence of HA-Ubi or HA-Ubi-KO did not induce interaction with TBK-1 (see Fig. S1a in the supplemental material).

MAVS undergoes K63-linked polyubiquitination following virus infection.

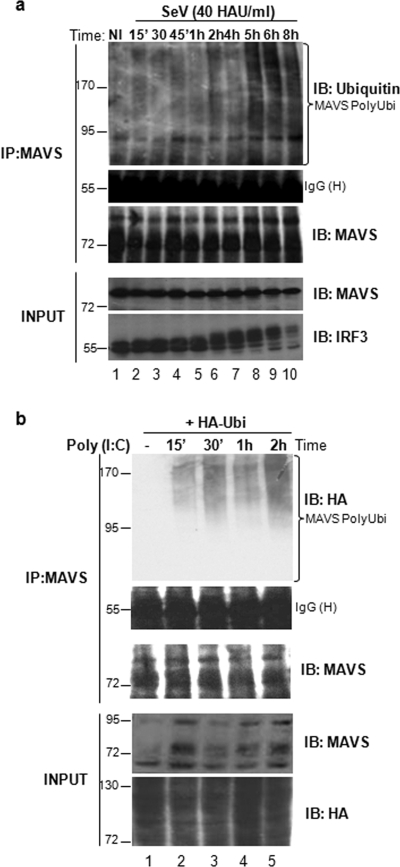

Next, endogenous MAVS was immunoprecipitated with anti-MAVS antibody at different times after SeV infection, and ubiquitination was detected with antiubiquitin antibody. The appearance of a slower-migrating smear demonstrated that MAVS ubiquitination occurred as early as 2 h postinfection and increased between 5 and 8 h (Fig. 2a, upper panel). Similarly, in HEK293 cells transfected with HA-tagged ubiquitin (HA-Ubi-wt), poly(I·C) stimulation led to endogenous MAVS ubiquitination as early as 15 min after treatment; ubiquitination was sustained for up to 2 h (Fig. 2b, upper panel). These results demonstrated that MAVS was ubiquitinated under physiological conditions of activation.

FIG. 2.

Endogenous MAVS is ubiquitinated following viral infection. (a) A549 cells were challenged with SeV (40 HAU/ml) for the indicated times followed by immunoprecipitation of endogenous MAVS with anti-MAVS cocktail. To remove possible interacting proteins, extracts were boiled in 1% SDS prior to immunoprecipitation. Immunoblotting with antiubiquitin antibody revealed a high-molecular-weight smear characteristic of ubiquitination (top panel). Equal amounts of immunoprecipitated MAVS are shown. Immunoblotting for IRF-3 phosphorylation was used to monitor activation of the IFN pathway (bottom panel). (b) Ubiquitination of MAVS following double-stranded DNA stimulation was assessed in HEK293 cells expressing HA-ubiquitin. Cells were challenged with poly(I·C) for the indicated times, and endogenous MAVS was immunoprecipitated with anti-MAVS cocktail. To remove possible interacting proteins, extracts were boiled in 1% SDS prior to immunoprecipitation. Ubiquitination signal was revealed by immunoblotting with anti-HA (top panel). Equal amounts of immunoprecipitated MAVS are shown.

Ubiquitination of MAVS was further investigated by an in vivo ubiquitination assay in which Myc-MAVS was expressed in the presence of increasing amounts of ubiquitin (HA-Ubi-wt). Immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody following immunoprecipitation of MAVS revealed a dose-dependent high-molecular-weight smear characteristic of ubiquitination whenever Myc-MAVS and HA-Ubi were coexpressed (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, ectopically expressed MAVS yielded discrete high-molecular-mass bands at 100 and 170 kDa that were observable by immunoblotting, indicating the presence of posttranslationally modified protein (Fig. 3b, lane 1). Ectopic expression of Ubi-KO resulted in the complete disappearance of these high-molecular-mass bands, demonstrating that they corresponded to polyubiquitinated forms of MAVS (Fig. 3b, lanes 2 and 3). These two experiments corroborate the initial observation that MAVS is a target for polyubiquitination.

FIG. 3.

MAVS undergoes K63- and K48-linked ubiquitination in vivo. (a) HEK293 cells were transfected with Myc-MAVS and increasing amounts of HA-ubiquitin as indicated. Whole-cell extracts were denatured and immunoprecipitated using an anti-Myc antibody. Immunoblotting with anti-HA revealed a high-molecular-weight smear characteristic of ubiquitination (top panel). Levels of immunoprecipitated MAVS and IgG heavy chain are shown. (b) HEK293 cells were transfected with Myc-MAVS and increasing amounts of HA-Ubi-KO as indicated. Immunoblotting with anti-MAVS antibody (N terminal) revealed unmodified MAVS protein and polyubiquitinated forms of MAVS that disappeared in the presence of Ubi-KO (top panel). Actin was used as a loading control (bottom panel). (c) HEK293 cells were transfected with Myc-MAVS, HA-Ubi, HA-Ubi-K48, HA-Ubi-KO, and HA-Ubi-K63 as indicated. Polyubiquitination of MAVS was detected as described for panel a.

The role of a ubiquitination signal on a particular target protein is determined by the type of linkage between ubiquitin molecules (37). K48-linked polyubiquitin chains generally target proteins for proteasomal degradation, whereas K63-linked polyubiquitin signals for protein activation or protein-protein interaction. To determine the type of Ub linkage of MAVS, ubiquitin constructs in which all lysines were mutated to arginine with the exception of either K48 or K63 (Ubi-K48 and Ubi-K63, respectively) were coexpressed with Myc-tagged MAVS; both HA-Ubi-K48 and HA-Ubi-K63 resulted in high-molecular-weight smears (Fig. 3c, lanes 4 and 6), similar to those observed in the presence of HA-Ubi (Fig. 3c, lane 3), demonstrating that MAVS undergoes both K48- and K63-linked polyubiquitination. As expected for a polyubiquitinated substrate, cotransfection of HA-Ubi-KO did not lead to formation of a smear (Fig. 3c, lane 5).

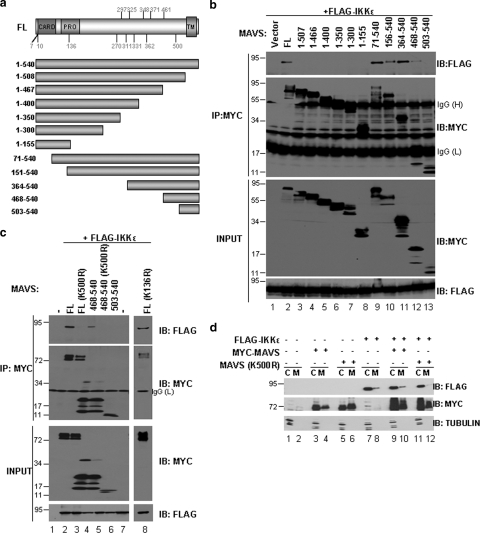

MAVS interaction with IKKɛ depends on K500.

To further delineate the role of MAVS ubiquitination in the recruitment of IKKɛ, it was important to identify potential lysine acceptor sites found within MAVS. To localize the IKKɛ-MAVS interaction, various truncated forms of MAVS were used in coimmunoprecipitation experiments (see the schematic representation in Fig. 4a). All C-terminal deletions of MAVS that removed the transmembrane domain (aa 1 to 155 and aa 1 to 507) eliminated the interaction with IKKɛ (Fig. 4b, lanes 3 to 8). Coimmunoprecipitation of N-terminal deletions revealed that the C-terminal region of MAVS was required for interaction with IKKɛ; MAVS with deletions up to aa 468 retained interaction with IKKɛ, whereas MAVS(503-540) no longer recruited the kinase (Fig. 4b, compare lanes 9 to 11, 12, and 13). This result demonstrated that IKKɛ was recruited to the C terminus of MAVS and that the transmembrane domain of MAVS was also necessary for this interaction, in agreement with previous results (23, 30).

FIG. 4.

IKKɛ interacts with the C terminus of MAVS and requires the TM domain. (a) Schematic representation of full-length MAVS (FL) and deletion constructs. The location of the CARD, proline-rich region (Pro), and TM domain are shown. Lysine residues of MAVS are also shown. (b) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated MAVS constructs. Coimmunoprecipitation was performed using an anti-Myc antibody (MAVS) followed by immunoblotting with an anti-Flag (IKKɛ) antibody (top panel). Immunoprecipitated MAVS constructs were revealed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc antibody (second panel). Equal input for Flag-IKKɛ is shown (bottom panel). (c) Cells were transfected with Flag-IKKɛ along with either wild-type MAVS full-length (FL), wild-type (468-540) truncation construct, or with mutants with a K500R substitution [FL-K500R or (468-540)-K500R]. A MAVS K136R mutant (FL-K136R) was used as a control. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments using an anti-Myc antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG revealed lack of interaction with IKKɛ for the K500R mutants (top panel). (d) Subcellular localization of MAVS and IKKɛ following overexpression of Myc-MAVS wt, Myc-MAVS-K500R, and Flag-IKKɛ. Mitochondrial and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies. Tubulin was used as a cytoplasmic marker.

Although MAVS contains several lysine residues (Fig. 4a), a single lysine at position 500 (K500) was identified within the aa 468 to 502 region. The requirement for K500 in the MAVS-IKKɛ interaction was examined by creating full-length and a truncated form of MAVS with the conservative arginine K500R substitution. The K500R substitution in wild-type MAVS or truncated MAVS(468-540) abolished interaction with IKKɛ (Fig. 4c, compare lanes 2 and 3 with lanes 4 and 5). Mutation of an unrelated lysine (K136R) did not alter IKKɛ recruitment (Fig. 4c, lane 8), thus confirming the specificity of the K500R mutation.

Cellular fractionation analysis demonstrated that MAVS(K500R) localized to the mitochondria as efficiently as wild-type MAVS, demonstrating that failure of MAVS(K500R) to interact with IKKɛ was not the result of improper protein localization (Fig. 4d, lanes 3 and 4 and lanes 5 and 6). Also, coexpression of MAVS(K500R) with IKKɛ reduced the ability of IKKɛ to localize to the mitochondria (Fig. 4d), thus further demonstrating that K500 is involved in the recruitment of IKKɛ to MAVS.

K500 is a K63-polyubiquitin acceptor lysine that mediates IKKɛ recruitment to the C terminus of MAVS.

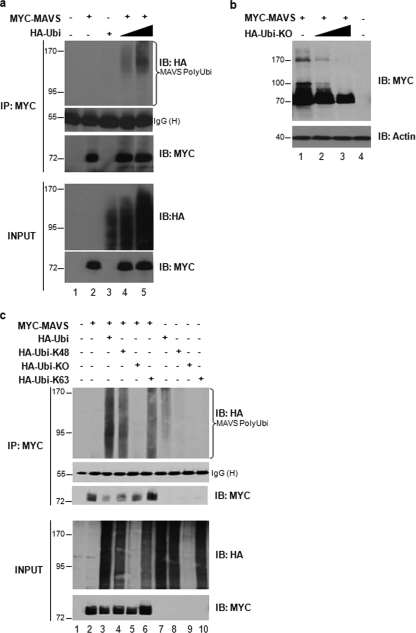

Next, the ability of K500 to undergo K63-linked polyubiquitination was examined. Ubiquitination was examined using an in vivo ubiquitination assay with ectopically expressed wild-type MAVS or MAVS K500R and Ubi-K63 in HEK293 cells (Fig. 5a). A sharp reduction in K63-linked ubiquitination was observed in K500R MAVS compared to wild type, indicating that K500 was an acceptor site for K63-linked ubiquitination (Fig. 5a, lane 6). Similarly, truncated MAVS (aa 468 to 540), either wild-type or K500R [MAVS(468-540)-K500R] was expressed in the presence of the ubiquitin wild type, K63, or K48 (Fig. 5b). MAVS(468-540) attached only Ubi-wt or Ubi-K63 but not Ubi-K48, demonstrating that K500 was an acceptor site for K63-linked ubiquitination only (Fig. 5b, lanes 7 to 9). The K500R mutant was no longer ubiquitinated, as demonstrated by a reduction in the intensity of the smear in the presence of Ubi or Ubi-K63 to background levels (Fig. 5b, compare lanes 7 and 10 with lanes 9 and 12). These results clearly demonstrated that MAVS K500 was an acceptor site for K63-linked ubiquitination and responsible for mediating the interaction with IKKɛ.

FIG. 5.

Lysine 500 of MAVS is an acceptor site for K63-linked ubiquitination. (a and b) HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Ubiquitination of MAVS was revealed by immunoprecipitation with anti-Myc antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (top panel). An equal amount of immunoprecipitated MAVS protein was observed (second panel). The IgG heavy chain is indicated. (c) HEK293 cells were transfected with either a Flag-IKKɛ or Flag-TBK-1 expression construct. Immunoprecipitation of either Flag-IKKɛ or Flag-TBK-1 was followed by incubation with a K63-ubiquitin polymer (Ub2-7) in increasing amounts. Poly-K63 linkage was revealed by immunoblotting with antiubiquitin antibody (top panel). An equal amount of either immunoprecipitated IKKɛ or TBK-1 protein is shown (second panel).

To demonstrate that recruitment of IKKɛ to MAVS K500 requires K63-linked polyubiquitination, an in vitro ubiquitin binding assay was performed to test the ability of IKKɛ to bind to recombinant K63-ubiquitin chains. Only IKKɛ, but not TBK-1, was capable of binding to K63 polymer chains (Fig. 5c). Thus, the IKKɛ interaction with MAVS requires K63-linked ubiquitination of K500, which acts as a scaffold for recruitment.

K500 ubiquitination negatively regulates ISG expression.

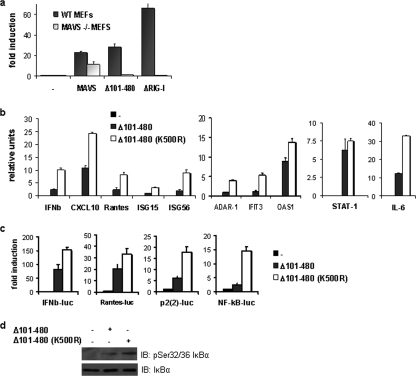

To determine the effect of K500 ubiquitination on downstream IFN signaling, the ability of wild-type and K500R forms of MAVS to induce mRNA expression of various ISGs was assessed by quantitative real-time PCR. Overall, mutation of K500 of full-length MAVS slightly increased the induction of many ISGs, although this increase was not statistically significant (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Therefore, the mini-MAVS construct (Δ101-480), containing the minimum CARD (aa 10 to 77) and TM domain (aa 514 to 535) necessary for activation of IFN signaling (25, 30, 58), was used to clarify the function of MAVS K500 ubiquitination. In wild-type and MAVS−/− MEFs, MAVS(Δ101-480) induced the innate response as reflected by the activation of the IFN-β promoter in wild-type MEFs but not in MAVS−/− MEFs (Fig. 6a). In contrast, full-length MAVS was active in both wild-type and MAVS−/− MEFs (Fig. 6a), suggesting that MAVS(Δ101-480) did not activate signaling on its own but rather required dimerization or oligomerization with intact MAVS molecules (3). In HeLa cells, while MAVS(Δ101-480) induced IFN-β, CXCL10, RANTES, ISG15, and ISG56 mRNA levels as well as the mRNA levels of IKKɛ-specific genes ADAR-1, IFIT3, and OAS1, MAVS K500R further increased mRNA expression of all tested genes by two- to fourfold (Fig. 6b). These data suggest that MAVS K500 ubiquitination functions to negatively modulate the IFN response. As a control, STAT-1 transcription was unchanged by MAVS K500R mutation. Reporter gene assays using the RANTES and IFN-β promoters further confirmed the real-time PCR results (Fig. 6c).

FIG. 6.

MAVS(Δ101-480) is functional but requires endogenous MAVS. (a) MAVS wt and MAVS−/− MEFs were transfected with a IFN-β-Luc reporter plasmid, and expression plasmids encoding either empty, MAVS wt, MAVS K500R, MAVS(Δ101-480), or MAVS(Δ101-480)-K500R as indicated. Luciferase activity was analyzed at 24 h posttransfection and activation was determined and compared to that with the empty vector; values represent averages ± standard deviations. Results are representative of at least three experiments run in triplicate. K500 ubiquitination negatively regulates ISG expression by affecting NF-κB signaling. (b) Quantitative PCR analysis of total RNA isolated from HeLa cells transfected with either empty vector, MAVS(Δ101-480), or MAVS(Δ101-480)-K500R. Relative expression levels of IFN-β, CXCL10, RANTES, IL-6, ISG15, ISG56, ADAR-1, IFIT3, OAS1 or STAT-1 versus GAPDH mRNA are shown. Data are representative of at least two experiments run in duplicate. (c) HeLa cells were transfected with IFN-β-Luc, RANTES-Luc, NF-κB-Luc, and p2(2)-Luc reporter plasmids and expression plasmids encoding MAVS(Δ101-480) or MAVS(Δ101-480)-K500R, as indicated. Luciferase activity was analyzed at 24 h posttransfection and activation was determined and compared to that with the empty vector; values represent the averages ± standard deviations. Results are representative of at least three experiments run in triplicate. (d) HeLa cells were transfected with either empty vector, MAVS(Δ101-480), or MAS(Δ101-480)-K500R. WCE were resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and IκBα phosphorylation was detected using a phospho-specific antibody. Total IκBα levels were also monitored.

Because interleukin-6 (IL-6) is specifically regulated by NF-κB and not by IRF-3/-7, upregulation of IL-6 mRNA by MAVS(Δ101-480)-K500R compared to wt MAVS(Δ101-480) suggested that MAVS ubiquitination also plays a negative role in NF-κB-dependent transcription (Fig. 6b). This idea was further substantiated using κB-specific promoters, tandem κB consensus sites (NF-κB-Luc) or tandem κB sequences found in the IFN-β promoter [p2(2)-Luc]; the MAVS(Δ101-480)-K500R mutant led to enhanced luciferase activity compared to wt MAVS(Δ101-480) (Fig. 6c). In addition, an increase in IκBα phosphorylation in the presence of MAVS(Δ101-480)-K500R was observed by immunoblotting (Fig. 6d). Together these results indicate that K63-linked ubiquitination of MAVS K500 exerts a negative effect on NF-κB-dependent promoters, including those regulating the expression of interferon-stimulated and proinflammatory genes.

IKKɛ is required to mediate the negative effect of K500.

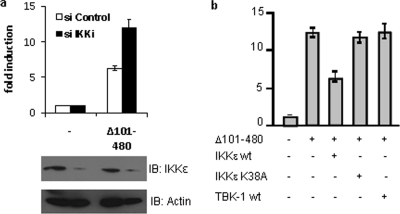

To confirm that the negative role of K500 ubiquitination is mediated through recruitment of IKKɛ, siRNAs were used to silence the expression of IKKɛ in HeLa cells. Induction of IFN-β promoter activity by MAVS(Δ101-480) was assessed in cells treated with either control or IKKɛ-specific siRNA (Fig. 7a). Ectopic MAVS(Δ101-480) expression resulted in a 6-fold induction of IFN-β promoter activity in control cells, but this activity was increased to 12-fold if IKKɛ expression was knocked down. Furthermore, ectopic expression of wild-type IKKɛ, but not the kinase-dead IKKɛ-K38A, led to a decrease in MAVS-mediated IFN-β promoter activity (Fig. 7b). Inhibition in IFN-β promoter activity was not observed upon ectopic expression of TBK-1. These results confirm that inhibition of NF-κB signaling by K500 ubiquitination of MAVS is mediated by the specific recruitment of functionally active IKKɛ to the mitochondria.

FIG. 7.

IKKɛ is required to mediate the negative effect of K500. (a) HeLa cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA against IKKɛ. At 48 h posttransfection, IFN-β-Luc reporter plasmid and expression plasmids encoding MAVS(Δ101-480) were also transfected. Luciferase activity was analyzed at 24 h posttransfection and activation was determined and compared to that for the empty vector; values represent the averages ± standard deviations. Results are representative of at least three experiments run in triplicate. Samples were also analyzed by immunoblotting for IKKɛ extinction by using an anti-IKKɛ antibody. Actin immunoblotting results are shown. (b) HeLa cells were transfected with an IFN-β-Luc reporter plasmid or expression plasmids encoding MAVS(Δ101-480), IKKɛ wt, IKKɛK38A, or TBK-1, as indicated. Luciferase activity was analyzed at 24 h posttransfection and activation was determined and compared to that for the empty vector; values represent the averages ± standard deviations. Results are representative of at least three experiments run in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

Ubiquitination has emerged as a key posttranslational modification that controls induction and shutdown of the interferon response (reviewed in references 1, 5, 6, 22). The mechanism of activation of IKKɛ and ΤΒΚ-1 by MAVS following RIG-I engagement involves formation of one or more multimeric complexes in which MAVS potentially interacts with multiple adapter molecules, such as TRAF-2/-3/-6, TRADD, FADD NEMO, RIP-1, TANK, and MITA/STING (17, 21, 30, 42, 43, 58, 61). However, the spatio-temporal events that regulate the IFN response upstream and downstream of IKKɛ and TBK-1 are incompletely understood. In the present study, we demonstrated that MAVS directly recruits IKKɛ to the mitochondria via a ubiquitin-dependent mechanism. Indeed, MAVS was ubiquitinated following viral infection, linking both K63- and K48- polyubiquitin chains. More specifically, lysine 500 of MAVS was identified as a K63-ubiquitin acceptor site that was recognized by IKKɛ and facilitated stable interaction with MAVS. Functionally, real-time PCR and gene expression assays suggested that the role of IKKɛ recruitment to MAVS was to decrease the expression of IFN-β and IFN-stimulated genes. Moreover, K500R mutation of MAVS correlated with an increase in specific NF-κB promoter activity, IL-6 mRNA expression, and IκBα phosphorylation, suggesting a negative role for the IKKɛ-MAVS association in the regulation of NF-κB activity.

Although it was clear that ubiquitination of MAVS at lysine 500 mediates recruitment of IKKɛ, we also observed that deletion constructs lacking the TM domain failed to interact with IKKɛ, suggesting that localization of MAVS at the mitochondrial membrane is required for interaction. A recent report demonstrating MAVS dimerization identified residues that are necessary for MAVS dimerization within the TM domain (3). Therefore, dimerization of MAVS may also be required for IKKɛ recruitment, in addition to K63-linked polyubiquitination of MAVS K500. Mapping experiments revealed that both N- and C-terminal sequences but not the kinase activity of IKKɛ are required for interaction with ubiquitinated MAVS (data not shown). In vitro ubiquitin binding assays revealed that IKKɛ was able to recognize K63-linked ubiquitin chains, a feature shared with the NEMO regulatory subunit of the IKK complex (57). These features indicated that IKKɛ should contain a ubiquitin binding grove, perhaps composed of both N- and C-terminal sequences, although further work is required to characterize this site.

In addition to MAVS K500 K63-polyubiquitination, MAVS can link K48-polyubiquitin chains following virus infection or poly(I·C) treatment, suggesting that MAVS may undergo multiple ubiquitination events, adding further complexity to the spatio-temporal regulation of the IFN response. Arimoto et al. previously reported that MAVS is the target for proteasomal degradation by the E3 ligase RNF125, a confirmation that MAVS can attach K48-polyubiquitin chains (2). Whether this event is necessary following virus infection to shut down the IFN response and the nature of the lysine(s) targeted for proteasomal degradation remain to be investigated. As part of this study, several candidate E3 ligases—TRAF3, TRAF6, and TRIM25—were examined as potential ligases mediating K63 linkage of Ub to MAVS K500. In vivo ubiquitination assays were performed in which MAVS, Ubi, and the E3 candidates were coexpressed; no conclusive evidence was obtained that MAVS ubiquitination was increased with these E3 ligases. Thus, we do not know which of the many E3 ligases may be responsible for K63 linkage of MAVS K500.

Cellular fractionation demonstrating IKKɛ relocation from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria upon virus infection suggested a stable association between MAVS and IKKɛ, since stringent mitochondria isolation procedures were unable to remove associated IKKɛ (Fig. 1b). Together with the in vitro ubiquitin binding assays and coimmunoprecipitation experiments, these observations argue that the interaction between MAVS and IKKɛ is direct. In contrast, TBK-1 did not localize to the mitochondrial fraction after virus infection and did not coimmunoprecipitate with overexpressed or endogenous MAVS following virus infection; the association between MAVS and TBK-1 appears to be indirect, potentially mediated by a novel adapter molecule. In this regard, two groups recently identified an adapter molecule named STING/MITA (stimulator of interferon genes/mediator of IRF-3 activation) that links TBK-1 to MAVS (17, 61); MITA was shown to bind to RIG-I, MAVS, and TBK-1, thus providing a link for IRF-3 activation. However, MITA had no effect on other signaling pathways, such as NF-κB (61). In contrast, STING localized to the endoplasmic reticulum and played a role upstream of TBK-1 but downstream of RIG-I and MAVS (17).

The negative role of MAVS K500 ubiquitination on the IFN response was identified by comparing mRNA expression levels of ISGs induced by wt MAVS(Δ101-480) and MAVS(Δ101-480)-K500R. The role of IKKɛ recruitment to ubiquitinated MAVS in this negative regulation was further confirmed by IFN-β reporter gene assays in the presence of IKKɛ-specific siRNA. Unraveling the negative role of MAVS K500 ubiquitination and IKKɛ recruitment on the IFN response required the use of mini-wt MAVS, MAVS(Δ101-480), and MAVS(Δ101-480)-K500R. Indeed, several reports have concluded that the CARD (aa 10 to 77) and TM domain (aa 514 to 535) of MAVS are two regions necessary for proper protein function and signaling (25, 30, 58). In wild-type and MAVS−/− MEFs (Fig. 6b and c), MAVS(Δ101-480) did not activate signaling on its own, but rather required dimerization with endogeneous MAVS molecules, as suggested by a recent report (3). Removal of the aa 101 to 480 region of MAVS appeared to unmask the ability of MAVS to activate the IFN response in MAVS−/− MEFs and revealed the function of ubiquitination-dependent recruitment of IKKɛ to MAVS. The aa 101 to 480 region of MAVS is known to recruit molecules such as IKKα/β and TRAF2/3/6 that play important roles in the active phase of the IFN response (30, 31, 42, 58). How the cell regulates the spatio-temporal events involved in the active phase and in the negative regulation of the antiviral response remains under investigation. However, we postulate that these events would be orchestrated through the exclusive recruitment of different adapter molecules to MAVS.

Increased expression of IL-6 mRNA and NF-κB-specific promoters by MAVS K500R suggested that Ubi-mediated recruitment of IKKɛ to the mitochondria not only decreased the IFN response but also negatively influenced proinflammatory and possibly prosurvival genes regulated by NF-κB. Importantly, the kinase activity of IKKɛ appeared to be necessary for IKKɛ to function in the modulation of NF-κB signaling (Fig. 7). Preliminary data argue that IKKɛ but not TBK-1 directly phosphorylates MAVS (unpublished results); however, further studies are under way to address the relationship between ubiquitination and phosphorylation of MAVS. Indeed, it is possible that K63-linked ubiquitination of K500 is required for IKKɛ recruitment to mediate MAVS phosphorylation. In support of this idea, Ning et al. recently demonstrated that K63-linked ubiquitination of C-terminal residues of IRF-7 occurred as a prelude to IRF-7 phosphorylation and activation (32).

We propose that two intracellular pools of IKKɛ can be identified in the cell following engagement of the RIG-I pathway: a cytoplasmic pool implicated in IRF-3/-7 activation and a mitochondrial pool implicated in the negative regulation of NF-κB. In the case of IRF activation, cytosolic TBK-1 and IKKɛ are activated by the recruitment of adapter molecules such as TRAF3, MITA/STING, and TANK to MAVS. This complex leads to the phosphorylation, dimerization, nuclear translocation, and specific DNA binding by IRF-3 and IRF-7 transcription factors. On the other hand, virus infection also promotes K63-linked ubiquitination of MAVS K500, leading to the recruitment of IKKɛ to the mitochondria, phosphorylation of MAVS, and modulation of NF-κB signaling.

In conclusion, the present study provides evidence that K63-linked ubiquitination of MAVS following viral infection modulates interaction with key components of the RIG-I signaling pathway and provides a mechanistic explanation for the differential recruitment of IKKɛ and TBK-1 to the mitochondrial membrane. This work also reveals a novel and unexpected function for IKKɛ in the negative regulation of NF-κB, which modulates the interferon and inflammatory responses and influences decisions between cell survival and apoptosis.

Supplementary Material

[Supplemental material]

Acknowledgments

We thank Z. Chen for kindly providing many reagents used in this study.

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the National Cancer Institute of Canada, and the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research, awarded to J.H. and R.L., and grants from L' Agence Nationale de la Recherche contre le SIDA, awarded to E.M. S.P. is the recipient of an FRSQ Bourse de Troisième Cycle (Doctorat), M.V. was the recipient of an FRM Bourse de Fin de Thèse, T.L.-A.N. was the recipient of a FRSQ postdoctoral fellowship, R.L. was the recipient of an FRSQ Senior Chercheur Boursier, and J.H. was the recipient of a CIHR Senior Investigator award.

Footnotes

▿

Published ahead of print on 20 April 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arguello, M. D., and J. Hiscott. 2007. Ub surprised: viral ovarian tumor domain proteases remove ubiquitin and ISG15 conjugates. Cell Host Microbe 2367-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arimoto, K., H. Takahashi, T. Hishiki, H. Konishi, T. Fujita, and K. Shimotohno. 2007. Negative regulation of the RIG-I signaling by the ubiquitin ligase RNF125. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1047500-7505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baril, M., M. E. Racine, F. Penin, and D. Lamarre. 2009. MAVS dimer is a crucial signaling component of innate immunity and the target of hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease. J. Virol. 831299-1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bibeau-Poirier, A., S. P. Gravel, J. F. Clement, S. Rolland, G. Rodier, P. Coulombe, J. Hiscott, N. Grandvaux, S. Meloche, and M. J. Servant. 2006. Involvement of the IκB kinase (IKK)-related kinases Tank-binding kinase 1/IKKi and Cullin-based ubiquitin ligases in IFN regulatory factor-3 degradation. J. Immunol. 1775059-5067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bibeau-Poirier, A., and M. J. Servant. 2008. Roles of ubiquitination in pattern-recognition receptors and type I interferon receptor signaling. Cytokine 43359-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chau, T. L., R. Gioia, J. S. Gatot, F. Patrascu, I. Carpentier, J. P. Chapelle, L. O'Neill, R. Beyaert, J. Piette, and A. Chariot. 2008. Are the IKKs and IKK-related kinases TBK1 and IKK-epsilon similarly activated? Trends Biochem. Sci. 33171-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clement, J. F., S. Meloche, and M. J. Servant. 2008. The IKK-related kinases: from innate immunity to oncogenesis. Cell Res. 18889-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ea, C. K., L. Deng, Z. P. Xia, G. Pineda, and Z. J. Chen. 2006. Activation of IKK by TNFα requires site-specific ubiquitination of RIP1 and polyubiquitin binding by NEMO. Mol. Cell 22245-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgerald, K. A., S. M. McWhirter, K. L. Faia, D. C. Rowe, E. Latz, D. T. Golenbock, A. J. Coyle, S. M. Liao, and T. Maniatis. 2003. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 4491-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujita, F., Y. Taniguchi, T. Kato, Y. Narita, A. Furuya, T. Ogawa, H. Sakurai, T. Joh, M. Itoh, M. Delhase, M. Karin, and M. Nakanishi. 2003. Identification of NAP1, a regulatory subunit of IκB kinase-related kinases that potentiates NF-κB signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 237780-7793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gack, M. U., Y. C. Shin, C. H. Joo, T. Urano, C. Liang, L. Sun, O. Takeuchi, S. Akira, Z. Chen, S. Inoue, and J. U. Jung. 2007. TRIM25 RING-finger E3 ubiquitin ligase is essential for RIG-I-mediated antiviral activity. Nature 446916-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gatot, J. S., R. Gioia, T. L. Chau, F. Patrascu, M. Warnier, P. Close, J. P. Chapelle, E. Muraille, K. Brown, U. Siebenlist, J. Piette, E. Dejardin, and A. Chariot. 2007. Lipopolysaccharide-mediated interferon regulatory factor activation involves TBK1-IKKɛ-dependent Lys63-linked polyubiquitination and phosphorylation of TANK/I-TRAF. J. Biol. Chem. 28231131-31146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh, S., and M. Karin. 2002. Missing pieces in the NF-κB puzzle. Cell 109(Suppl.)S81-S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris, J., S. Oliere, S. Sharma, Q. Sun, R. Lin, J. Hiscott, and N. Grandvaux. 2006. Nuclear accumulation of cRel following C-terminal phosphorylation by TBK1/IKK epsilon. J. Immunol. 1772527-2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hemmi, H., O. Takeuchi, S. Sato, M. Yamamoto, T. Kaisho, H. Sanjo, T. Kawai, K. Hoshino, K. Takeda, and S. Akira. 2004. The roles of two IκB kinase-related kinases in lipopolysaccharide and double stranded RNA signaling and viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 1991641-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiscott, J., J. Lacoste, and R. Lin. 2006. Recruitment of an interferon molecular signaling complex to the mitochondrial membrane: disruption by hepatitis C virus NS3-4A protease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 721477-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa, H., and G. N. Barber. 2008. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature 455674-678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwasaki, A., and R. Medzhitov. 2004. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 5987-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato, H., O. Takeuchi, S. Sato, M. Yoneyama, M. Yamamoto, K. Matsui, S. Uematsu, A. Jung, T. Kawai, K. J. Ishii, O. Yamaguchi, K. Otsu, T. Tsujimura, C. S. Koh, C. Reis e Sousa, Y. Matsuura, T. Fujita, and S. Akira. 2006. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature 441101-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawai, T., and S. Akira. 2006. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat. Immunol. 7131-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawai, T., K. Takahashi, S. Sato, C. Coban, H. Kumar, H. Kato, K. J. Ishii, O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 2005. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat. Immunol. 6981-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kayagaki, N., Q. Phung, S. Chan, R. Chaudhari, C. Quan, K. M. O'Rourke, M. Eby, E. Pietras, G. Cheng, J. F. Bazan, Z. Zhang, D. Arnott, and V. M. Dixit. 2007. DUBA: a deubiquitinase that regulates type I interferon production. Science 3181628-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komuro, A., and C. M. Horvath. 2006. RNA- and virus-independent inhibition of antiviral signaling by RNA helicase LGP2. J. Virol. 8012332-12342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar, H., T. Kawai, H. Kato, S. Sato, K. Takahashi, C. Coban, M. Yamamoto, S. Uematsu, K. J. Ishii, O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 2006. Essential role of IPS-1 in innate immune responses against RNA viruses. J. Exp. Med. 2031795-1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin, R., J. Lacoste, P. Nakhaei, Q. Sun, L. Yang, S. Paz, P. Wilkinson, I. Julkunen, D. Vitour, E. Meurs, and J. Hiscott. 2006. Dissociation of a MAVS/IPS-1/VISA/Cardif-IKKɛ molecular complex from the mitochondrial outer membrane by hepatitis C virus NS3-4A proteolytic cleavage. J. Virol. 806072-6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin, R., Y. Mamane, and J. Hiscott. 1999. Structural and functional analysis of interferon regulatory factor 3: localization of the transactivation and autoinhibitory domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 192465-2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loo, Y. M., and M. Gale, Jr. 2007. Viral regulation and evasion of the host response. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 316295-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsui, K., Y. Kumagai, H. Kato, S. Sato, T. Kawagoe, S. Uematsu, O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 2006. Cutting edge: role of TANK-binding kinase 1 and inducible IκB kinase in IFN responses against viruses in innate immune cells. J. Immunol. 1775785-5789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McWhirter, S. M., K. A. Fitzgerald, J. Rosains, D. C. Rowe, D. T. Golenbock, and T. Maniatis. 2004. IFN-regulatory factor 3-dependent gene expression is defective in Tbk1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101233-238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meylan, E., J. Curran, K. Hofmann, D. Moradpour, M. Binder, R. Bartenschlager, and J. Tschopp. 2005. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature 4371167-1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michallet, M. C., E. Meylan, M. A. Ermolaeva, J. Vazquez, M. Rebsamen, J. Curran, H. Poeck, M. Bscheider, G. Hartmann, M. Konig, U. Kalinke, M. Pasparakis, and J. Tschopp. 2008. TRADD protein is an essential component of the RIG-like helicase antiviral pathway. Immunity 28651-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ning, S., A. D. Campos, B. G. Darnay, G. L. Bentz, and J. S. Pagano. 2008. TRAF6 and the three C-terminal lysine sites on IRF7 are required for its ubiquitination-mediated activation by the tumor necrosis factor receptor family member latent membrane protein 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 286536-6546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oganesyan, G., S. K. Saha, B. Guo, J. Q. He, A. Shahangian, B. Zarnegar, A. Perry, and G. Cheng. 2006. Critical role of TRAF3 in the Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent antiviral response. Nature 439208-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paz, S., Q. Sun, P. Nakhaei, R. Romieu-Mourez, D. Goubau, I. Julkunen, R. Lin, and J. Hiscott. 2006. Induction of IRF-3 and IRF-7 phosphorylation following activation of the RIG-I pathway. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand) 5217-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perry, A. K., E. K. Chow, J. B. Goodnough, W. C. Yeh, and G. Cheng. 2004. Differential requirement for TANK-binding kinase-1 in type I interferon responses to toll-like receptor activation and viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 1991651-1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters, R. T., S. M. Liao, and T. Maniatis. 2000. IKKɛ is part of a novel PMA-inducible IκB kinase complex. Mol. Cell 5513-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pickart, C. M., and D. Fushman. 2004. Polyubiquitin chains: polymeric protein signals. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 8610-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pomerantz, J. L., and D. Baltimore. 1999. NF-κB activation by a signaling complex containing TRAF2, TANK and TBK1, a novel IKK-related kinase. EMBO J. 186694-6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reich, N. C. 2007. STAT dynamics. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 18511-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Remoli, M. E., E. Giacomini, G. Lutfalla, E. Dondi, G. Orefici, A. Battistini, G. Uze, S. Pellegrini, and E. M. Coccia. 2002. Selective expression of type I IFN genes in human dendritic cells infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 169366-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saha, S. K., and G. Cheng. 2006. TRAF3: a new regulator of type I interferons. Cell Cycle 5804-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saha, S. K., E. M. Pietras, J. Q. He, J. R. Kang, S. Y. Liu, G. Oganesyan, A. Shahangian, B. Zarnegar, T. L. Shiba, Y. Wang, and G. Cheng. 2006. Regulation of antiviral responses by a direct and specific interaction between TRAF3 and Cardif. EMBO J. 253257-3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sebban-Benin, H., A. Pescatore, F. Fusco, V. Pascuale, J. Gautheron, S. Yamaoka, A. Moncla, M. V. Ursini, and G. Courtois. 2007. Identification of TRAF6-dependent NEMO polyubiquitination sites through analysis of a new NEMO mutation causing incontinentia pigmenti. Hum. Mol. Genet. 162805-2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Servant, M. J., N. Grandvaux, B. R. tenOever, D. Duguay, R. Lin, and J. Hiscott. 2003. Identification of the minimal phosphoacceptor site required for in vivo activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 in response to virus and double-stranded RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2789441-9447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seth, R. B., L. Sun, C. K. Ea, and Z. J. Chen. 2005. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-κB and IRF 3. Cell 122669-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma, S., B. R. tenOever, N. Grandvaux, G. P. Zhou, R. Lin, and J. Hiscott. 2003. Triggering the interferon antiviral response through an IKK-related pathway. Science 3001148-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimada, T., T. Kawai, K. Takeda, M. Matsumoto, J. Inoue, Y. Tatsumi, A. Kanamaru, and S. Akira. 1999. IKK-i, a novel lipopolysaccharide-inducible kinase that is related to IκB kinases. Int. Immunol. 111357-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solis, M., R. Romieu-Mourez, D. Goubau, N. Grandvaux, T. Mesplede, I. Julkunen, A. Nardin, M. Salcedo, and J. Hiscott. 2007. Involvement of TBK1 and IKKɛ in lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of the interferon response in primary human macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 37528-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun, Q., L. Sun, H. H. Liu, X. Chen, R. B. Seth, J. Forman, and Z. J. Chen. 2006. The specific and essential role of MAVS in antiviral innate immune responses. Immunity 24633-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takeuchi, O., and S. Akira. 2008. MDA5/RIG-I and virus recognition. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.tenOever, B. R., S. L. Ng, M. A. Chua, S. M. McWhirter, A. Garcia-Sastre, and T. Maniatis. 2007. Multiple functions of the IKK-related kinase IKKɛ in interferon-mediated antiviral immunity. Science 3151274-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.tenOever, B. R., S. Sharma, W. Zou, Q. Sun, N. Grandvaux, I. Julkunen, H. Hemmi, M. Yamamoto, S. Akira, W. C. Yeh, R. Lin, and J. Hiscott. 2004. Activation of TBK1 and IKKɛ kinases by vesicular stomatitis virus infection and the role of viral ribonucleoprotein in the development of interferon antiviral immunity. J. Virol. 7810636-10649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson, A. J., and S. A. Locarnini. 2007. Toll-like receptors, RIG-I-like RNA helicases and the antiviral innate immune response. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85435-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Boxel-Dezaire, A. H., M. R. Rani, and G. R. Stark. 2006. Complex modulation of cell type-specific signaling in response to type I interferons. Immunity 25361-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wagner, S., I. Carpentier, V. Rogov, M. Kreike, F. Ikeda, F. Lohr, C. J. Wu, J. D. Ashwell, V. Dotsch, I. Dikic, and R. Beyaert. 2008. Ubiquitin binding mediates the NF-κB inhibitory potential of ABIN proteins. Oncogene 273739-3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wertz, I. E., K. M. O'Rourke, H. Zhou, M. Eby, L. Aravind, S. Seshagiri, P. Wu, C. Wiesmann, R. Baker, D. L. Boone, A. Ma, E. V. Koonin, and V. M. Dixit. 2004. De-ubiquitination and ubiquitin ligase domains of A20 downregulate NF-κB signalling. Nature 430694-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu, C. J., D. B. Conze, T. Li, S. M. Srinivasula, and J. D. Ashwell. 2006. Sensing of Lys 63-linked polyubiquitination by NEMO is a key event in NF-κB activation [corrected]. Nat. Cell Biol. 8398-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu, L. G., Y. Y. Wang, K. J. Han, L. Y. Li, Z. Zhai, and H. B. Shu. 2005. VISA is an adapter protein required for virus-triggered IFN-beta signaling. Mol. Cell 19727-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoneyama, M., M. Kikuchi, T. Natsukawa, N. Shinobu, T. Imaizumi, M. Miyagishi, K. Taira, S. Akira, and T. Fujita. 2004. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat. Immunol. 5730-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao, T., L. Yang, Q. Sun, M. Arguello, D. W. Ballard, J. Hiscott, and R. Lin. 2007. The NEMO adaptor bridges the nuclear factor-κB and interferon regulatory factor signaling pathways. Nat. Immunol. 8592-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhong, B., Y. Yang, S. Li, Y. Y. Wang, Y. Li, F. Diao, C. Lei, X. He, L. Zhang, P. Tien, and H. B. Shu. 2008. The adaptor protein MITA links virus-sensing receptors to IRF3 transcription factor activation. Immunity 29538-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

[Supplemental material]