IL-17 signaling in host defense and inflammatory diseases (original) (raw)

Abstract

Interleukin (IL)-17, the signature cytokine secreted by T helper (Th) 17 cells, plays important roles in host defense against extracellular bacterial infection and fungal infection and contributes to the pathogenesis of various autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Here we review the recent advances in IL-17-mediated functions with emphasis on the studies of IL-17-mediated signal transduction, providing perspective on potential drug targets for the treatment of autoimmune inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: inflammation, interleukin-17, signaling

Introduction

Two decades ago, T helper (Th) cells were divided into Th1 and Th2 subgroups according to their distinct cytokine secretions and functions.1, 2 Interleukin (IL)-12-activated Th1 cells secrete interferon-γ, which mediates cellular immunity, while Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, which mediate humoral immunity. However, some intriguing phenomena were observed that cannot be explained by the Th1/Th2 paradigm. Interferon-γ- and IL-12-deficient mice were unexpectedly found to be more susceptible to experimentally induced autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE).3, 4 This paradox remained elusive until the discovery of the Th17 subset (producing IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21 and IL-22) of Th cells.5 It is now known that while Th17 cells play a major role in EAE development, the Th1 cytokine, interferon-γ, inhibits Th17 development. Importantly, recent data demonstrate that both Th1 and Th17 cells can independently induce EAE, possibly through different mechanisms.6, 7, 8, 9 Th17 cells have also been found to play a critical role in host defense. Enormous progress has been made in understanding the regulation of Th17 development, which has been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 The functionality and pathogenicity of Th17 cells are conferred by the cytokines that they produce. In this review, we focus on IL-17, the signature cytokine of Th17 cells, which has been shown to play an essential role in host defense and inflammatory diseases.

Functions of the IL-17 family

IL-17 and IL-17 receptor family

Six IL-17 family members have been discovered: IL-17A (also called IL-17), IL-17B, IL-17C, IL-17D, IL-17E (also named IL-25) and IL-17F.16 IL-17 (IL-17A) is the prototype of the IL-17 family and IL-17F is most closely related to IL-17A in regard to its protein sequence. IL-17F has been crystallized, and it displays a three-dimensional cysteine-knot fold architecture.17 The IL-17 family members function as either homodimers or heterodimers.18, 19 IL-17A, IL-17F and IL-17E are important proinflammatory cytokines, although the functions of IL-17B, IL-17C and IL-17D are still poorly understood.

Five IL-17 receptors have been identified, namely, IL-17RA, IL-17RB, IL-17RC, IL-17RD and IL-17RE. IL-17RA (also called IL-17R) is the best characterized receptor.16, 20, 21, 22 IL-17RA can be bound by both IL-17 and IL-17F, but it has 10-fold more affinity for IL-17 than for IL-17F. Accordingly, IL-17 can induce a much stronger inflammatory response than IL-17F. IL-17RC was found to be a coreceptor for IL-17R, although both receptors are not always coexpressed in cells. While both IL-17E and IL-17B bind IL-17RB, inducing the production of Th2 cytokines, IL-17E is much more potent in cytokine induction than IL-17B. The ligand for IL-17RD is still unknown. IL-17C may be the ligand for IL-17RE, but the functional link has not yet been identified. Recent studies have shown that binding of the first receptor to the IL-17 cytokines modulated the affinity and specificity of the second binding event, thereby promoting heterodimeric versus homodimeric complex formation.23

Host defense

Recent studies showed that IL-17 and IL-17F, which are induced during bacterial infection, play critical roles in host defense and inflammation. The first study of IL-17-mediated functions in host defense was based on the Klebsiella pneumonia lung infection model in IL-17R-deficient mice.24 IL-17R-deficient mice were highly susceptible to K. pneumonia infection due to significant reduction of chemokine production and, consequently, a significant delay in neutrophil recruitment into the alveolar space.25 IL-17 is also important for host defense against Porphyromonas gingivalis oral infection. IL-17R-deficient mice were shown to be substantially more susceptible to infection-induced periodontal disease due to defects in chemokine production and antibacterial neutrophil recruitment.26 In addition to its role in host defense against extracellular bacterial infection, IL-17 has recently been shown to be important in protection against fungal and parasitic infection. IL-17R-deficient mice were reported to have increased kidney fungal burden and decreased survival upon Candida albicans challenge.27 Infection with toxoplasma, a protozoan pathogen, in IL-17R-deficient mice resulted in a decreased survival rate and increased parasite burden due to reduced neutrophil recruitment.28 Interestingly, IL-17 was also essential for host resistance to the intracellular pathogen Francisella tularensis.29 While the function of IL-17 in viral infection is less clear, some studies suggest that IL-17 plays a pathogenic role, instead of protective one, during viral infection.30, 31

Inflammatory diseases

IL-17 induces sustained production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, GM-CSF, TNF-α and IL-6 as well as chemokines, including CXCL1 (KC), CCL2 (MCP-1), CXCL2 (MIP-2), CCL7 (MCP-3) and CCL20 (MIP-3A). IL-17 can also act synergistically with IL-1 and TNF for the induction of proinflammatory genes. IL-17 levels are elevated in the sera from patients with asthma and in the synovial fluids from patients with arthritis. As outlined below, in vivo studies demonstrated the critical role of IL-17 in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

Autoimmune diseases

While the etiology of autoimmune diseases remains unclear, it is generally believed that the break of central and peripheral tolerance leads to the escape of autoreactive T and B cells from normal selection. These autoreactive T and B cells are activated and expanded when they encounter their cognate ‘self'-antigens and they become pathogenic, resulting in humoral and cellular abnormality. The pathogenic autoreactive lymphocytes eventually lead to organ-specific diseases (such as multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes mellitus) or systemic autoimmune diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematosus and primary Sjögren syndrome) through their infiltration into the tissues, which is followed by exacerbated inflammatory responses and tissue destruction.32, 33

While Th1 cells play an important role in the development of autoimmune diseases, recent studies have demonstrated the potent pathogenic role of Th17 cells and its hallmark cytokine, IL-17, in autoimmune diseases. IL-17 is elevated in patients with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, asthma and psoriasis.16 Gene targeting through transgenic and knockout mouse models have supported the association of IL-17 with the development of autoimmunity. IL-17- or IL-17R-deficient mice are resistant to type II collagen-induced arthritis and streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis.34, 35 IL-17 and IL-17R deficiency also attenuates the immune infiltration in the brain during the development of experimental EAE.36, 37 Importantly, IL-17 antibody or IL17R-F_c_ blockage can efficiently reduce autoimmune pathology in arthritis and EAE, suggesting the potential clinical application of these reagents for treatment of autoimmune diseases.38, 39

Other inflammatory diseases

The link between chronic inflammation and cancer has been well established, including both anti- and protumorigenesis effects. Therefore, it is not surprising that IL-17 has been associated with the pathogenesis of certain malignancies. IL-17 has been shown to have angiogenic effects both in vitro and in vivo. Tumor cell lines transfected to overexpress IL-17 led to significantly enlarged tumors in nude mice. Consistently, IL-17 was found to be increased in patients with cancers such as ovarian cancer, Hodgkin's lymphoma, prostatic carcinoma and cervical cancer.20 Interestingly, tumor models in IL-17-deficient mice produced seemingly opposite results. In a model of B16 melanoma and MB49 bladder carcinoma, tumor growth was reduced in IL-17-deficient mice, partly due to decreased IL-6–Stat3-mediated inflammatory and survival effects.40 Nevertheless, in a model of MC38 colon cancer, tumor growth and metastasis to the lung were enhanced in IL-17-deficient mice, suggesting decreased antitumor immunity in these mice.41 These results indicate that IL-17-mediated inflammatory responses have both pro- and antitumorigenesis effects, which need to be taken into consideration when targeting IL-17 signaling for cancer therapy. It is important to note that IL-17 has also been associated with other inflammatory diseases, including TNF-α-induced shock and atherosclerosis, although the underlining molecular mechanisms need to be identified.

IL-17 signaling

IL-17A-mediated signaling

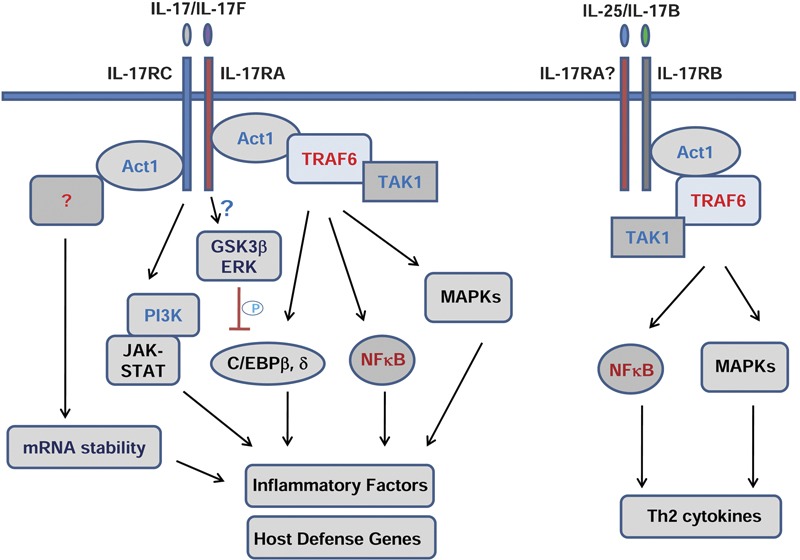

Because IL-17 has been implicated in many autoimmune inflammatory diseases, much effort has now been directed toward the understanding of IL-17-mediated signaling mechanism(s). While IL-17 has been shown to activate many common proinflammatory signaling pathways, including NF-κB, mitogen-activated protein kinases (JNK, P38 and ERK), CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs), phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and Stats, the proximal receptor signaling and subsequent intermediate signaling components remain unclear. Recently, studies have begun to unravel some important signaling intermediates (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

IL-17 family-mediated signaling. C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteins; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinases; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; TAK1, transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase-1; Th, T helper; TRAF6, tumor-necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6.

tumor-necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6)

The adaptor TRAF6 was found to be the first intermediate signaling molecule and was shown to be essential for IL-17-mediated NF-κB and JNK activation from studies of TRAF6-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts.42 Consistently, IL-17-induced IL-6 was abolished in the TRAF6-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts.

Act1

IL-17 receptors belong to a newly defined similar expression to fibroblast growth factor genes and IL-17Rs (SEFIR) protein family; they have a conserved sequence segment called SEFIR in their cytoplasmic domain.43 The SEFIR domain contains conserved motifs similar to those found in Toll-IL-1R domain containing proteins, comprising the STIR domain superfamily. Like the Toll-IL-1R domain, it is speculated that the SEFIR domain is responsible for the homotypical interaction between proteins. However, the key IL-1/Toll signaling molecules, MyD88 and IRAK1, are not involved in IL-17-mediated signaling and gene induction.44 We previously cloned and identified Act1 (NF-κB activator 1) as an adaptor molecule with the ability to activate NF-κB. Act1 was later shown to negatively regulate CD40- and B cell-activating factor belonging to TNF family (BAFF) mediated B-cell survival and autoimmunity.45, 46 Act1 contains two TRAF-binding sites, a helix–loop–helix domain at the N-terminus, and a U-box-like region and a coiled-coil domain at the C-terminus. Importantly, it was recently found that Act1 contains a SEFIR domain in its coiled-coil region at the C-terminus, and therefore, Act1 becomes a member of the SEFIR protein family. We and others have reported that Act1 is an essential adaptor molecule in the IL-17-mediated signaling pathways,44, 47 recruited to the IL-17R upon IL-17 stimulation through SEFIR–SEFIR domain interaction. Our recent study indicated that Act1 is a novel, bona fide E3 ubiquitin ligase through its U-box-like region, whose activity is essential for IL-17-mediated signaling pathways and inflammatory gene expression. By utilizing the Ubc13/Uev1A E2 complex, Act1 mediates Lys 63-linked ubiquitination of TRAF6, which is critical for the ability of TRAF6 to mediate IL-17-induced NF-κB activation through the activation of transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) and IκB kinase.48, 49

JAK

A recent investigation observed that IL-17 can activate JAK1/2 and PI3K pathway, which coordinate with the NF-κB activating pathway of Act1/TRAF6/TAK1 for gene induction, especially for host defense genes (e.g., human defensin 2) in human airway epithelial cells.50 Interestingly, a recent report showed that Stat3 is critical for IL-17-mediated CCL11 expression in human airway smooth muscle cells.51 However, more direct evidence for the roles of JAK/PI3K and JAK/Stat in IL-17 signaling are needed to avoid secondary effects because JAKs can be strongly activated by IL-17-induced cytokines, such as IL-6.

mRNA stability

IL-17 can synergize with TNF or IL-1 in inflammatory gene induction in which post-transcriptional effects through mRNA stability play a major role. Act1 is required for IL-17-mediated stability of KC mRNA induced by TNF-α.47 Interestingly, TRAF6 was actually dispensable for IL-17-induced mRNA stability, although it is required for IL-17-induced NF-κB and JNK activation, and inflammatory gene induction, suggesting that key linkers for Act1-mediated mRNA stability in IL-17 signaling are still missing.52 Further investigations in this direction will advance our understanding of the mechanisms of IL-17-mediated inflammatory effects.

Negative regulation

One important question is whether and how IL-17 signaling is negatively regulated to adequately prevent inflammatory disorders. It has recently been shown that blockade of the PI3K pathway led to upregulation of IL-17RA, which can potentially enhance IL-17 signaling.53 IL-17 has been found to directly activate phosphorylation cascades to inactivate C/EBPβ, a critical transcription factor for mediating induction of IL-17-responsive genes.54 IL-17 signaling activates ERK to phosphorylate Thr-188 of C/EBPβ, which is required for Thr-179 phosphorylation of C/EBPβ by glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β). The two phosphorylation events are probably activated through different signaling pathways as they require different domains in the IL-17R. Phosphorylation of these two sites leads to C/EBPβ inactivation. Although recent studies have started to dissect the negative regulation of IL-17 signaling, further research is still needed for the thorough understanding of IL-17 control signaling at different levels.

Signaling of other IL-17 members

The signaling mediated by other IL-17 ligands or IL-17 receptors is still poorly characterized. IL-17F, like IL-17, also binds to IL-17R and IL-17RC and uses similar signaling molecules, such as Act1 and TRAF6.18 However, the in vivo functions of IL-17 and IL-17F are different, suggesting that they might mediate differential signaling pathways. IL-17E (also called IL-25) is the most divergent member of the IL-17 family. Recent studies showed that IL-25 functions as an important mediator of Th2 responses.55, 56, 57, 58, 59 IL-25 is produced by airway epithelial cells, by T lymphocytes of the CD4+ subset with a Th2 profile and by innate effector eosinophils and basophils. While recombinant IL-25 can induce Th2 immunity, elevated IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, eosinophilia and immunoglobulin E, endogenous IL-25 is critical for allergen-induced pulmonary airway hyper-responsiveness and inflammation in a mouse model of asthma. These findings clearly demonstrate that IL-25 is an important mediator of Th2 responses, suggesting that IL-25 lies upstream of the classical Th2 cytokine pathway. Similar to IL-17 signaling, TRAF6 has been shown to be involved in IL-25-mediated signaling.60 We recently reported that Act1 is also an essential signaling molecule for IL-25 receptor signaling. Mice deficient in Act1 have abolished IL-25-induced expression of cytokines (IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13) and chemokines (eotaxin, TARC and RANTES) in the airway and reduced allergen-induced pulmonary eosinophilia. Importantly, Act1 deficiency in epithelial cells results in diminished Th2 responses and less lung inflammation. These findings provide the rationale for us to investigate the detailed molecular mechanisms of how IL-25 mediates Th2 immunity and to apply this knowledge to the development of new therapeutics for the treatment of asthma.

While IL-25 binds to IL-17RB, an interesting finding is that IL-17RA is required for IL-25-mediated function in vivo,61 indicating that IL-25 might use the IL-17RA/IL-17RB complex for signaling. Interestingly, we and others recently found that IL-25 stimulation also leads to the recruitment of Act1 and TRAF6 to IL-17RB, suggesting that IL-25 signaling may use similar signaling intermediates as those used in the IL-17-mediated pathway.62, 63 However, because the in vivo functions and the target genes of IL-17 and IL-25 are quite different, the two cytokines probably also mediate specific/differential signaling as well. Future investigation into these molecular mechanisms should advance our understanding of whether and how the same and/or different signaling molecules are used in IL-17 versus IL-25 signaling for different functions. The ligand for IL-17RD is still not known, while IL-17C may be the ligand for IL-17RE. Recent studies showed that IL-17RD may work with IL-17R to potentiate IL-17 signaling,64 while overexpression of IL-17RE was shown to activate the ERK pathway.65 The in vivo functions would require studies of mice deficient in these receptors.

The in vivo functions of signaling intermediates

Act1, TRAF6 and TAK1 are the known intermediate signaling molecules in the IL-17 pathway and potentially other IL-17 family members mediate signaling via these proteins. The in vivo function for TRAF6 and TAK1 in IL-17-mediated signaling is lacking because TRAF6- and TAK1-deficient mice are embryonically lethal. Considering the importance of Act1 in IL-17 signaling, Act1-deficient mice provide a useful model system to investigate the effector function(s) of IL-17 signaling in vivo. While IL-17 plays an essential role in the development of EAE.36, 37, 39 it remains unclear how IL-17-mediated signaling occurs in different cellular compartments and participates in the central nervous system (CNS) in EAE. Li and colleagues have now shown that Th17 cells are robustly generated in Act1-deficient mice and normally infiltrate the Act1-deficient CNS but fail to recruit hematogenously derived lymphocytes, neutrophils and macrophages into the CNS.47, 66 Importantly, Act1 deficiency in endothelial cells or in macrophages/microglia did not substantially impact the development of EAE. However, targeted Act1 deficiency in CNS-resident neuroepithelial cells significantly delayed EAE onset and significantly reduced EAE severity regardless of whether EAE was induced by active immunization or adoptive transfer of myelin-specific Th17 cells. Astrocytes are neuroepithelial, and their direct contacts with the glia limitans and the cerebral vasculature enable them to couple inflammatory cytokine expression to invasion of the CNS by hematogenous leukocytes. Importantly, we observed that CNS-resident astrocytes were highly responsive to IL-17 and that IL-17-mediated inflammatory gene induction was impaired in Act1-deficient astrocytes. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that IL-17 signals to astrocytes in an Act1-dependent fashion to amplify the inflammatory cascade, which is essential for EAE pathogenesis.

It has also been reported that IL-17 is elevated in intestinal tissues and serum of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. It was shown that the development of 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis or dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis is attenuated in IL-17R-deficient mice or IL-17A-deficient mice, respectively, indicating the importance of IL-17 signaling in intestinal inflammation.67, 68 Interestingly, a recent study showed a protective role of IL-17A in T cell-mediated intestinal inflammation, in which IL-17A directly inhibits Th1 development and therefore Th1-mediated colitis.69, 70 suggesting that IL-17 signaling may exhibit cell type-specific roles that need to be identified through investigation of IL-17R cell type-specific deficient mice. Because Act1 is highly expressed in colonic epithelial cells and IL-17 can effectively upregulate the expression of inflammatory genes in epithelial cells, it was hypothesized that the epithelial cells might be the major cell type responsible for the impact of IL-17-mediated inflammatory reactions on the development of inflammatory bowel disease. Indeed, the epithelial-specific Act1-deficient mice had reduced dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis, which strongly indicates that Act1 expression in colonic epithelium plays a critical role in IL-17-dependent intestinal inflammation.47 It would be interesting to know if specific deletion of Act1 in T cells has a protective role in dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis as shown in IL-17- or IL-17R-deficient mice.

Act1 will be an invaluable mouse model for studying IL-17-mediated functions. As Act1 is likely to be the common signaling adaptor for the IL-17 family members, the phenotypes of Act1-deficient mice could be more severe and complicated than those of IL-17R- or IL-17-deficient mice. Much work is needed to investigate the potential roles of Act1 in host defense and the development of other inflammatory diseases in addition to the checked EAE and colitis, in comparison with IL-17R- or IL-17-deficient mice. Because the conditional IL-17R knockout mouse is still not available, the Act1-floxed mouse will be important to dissect contributions of different cell types to IL-17-mediated functions and to pathology of various inflammatory diseases.

Conclusion

IL-17, the signature cytokine secreted by Th17 cells, is required for host defense against extracellular bacterial infection and fungal infection, and contributes to the pathogenesis of various autoimmune inflammatory diseases. IL-17 family members have become important targets for treating different forms of inflammatory disorders, including the use of IL-17 decoy receptors and IL-17 blocking antibodies. As IL-17 has an important protective role in host defense, blocking IL-17-mediated functions may generate side effects, including increased susceptibility to infection. Further investigations into the molecular signaling and subsequent functions of the IL-17 family can potentially provide ideal targets for alleviating symptoms associated with inflammatory diseases without compromising host defense.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the American Asthma Foundation and the Multiple Sclerosis Society to Xiaoxia Li, and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 30930084, 30871298 and 30928025), 973 Program (No. 2010CB529705), Chinese Academy of Sciences (Nos. KSCX2-YW-R-146 and KSCX1-YW-22) and Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (No. 08PJ14110).

References

- Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glimcher LH, Murphy KM. Lineage commitment in the immune system: the T helper lymphocyte grows up. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1693–1711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakowski M, Owens T. Interferon-gamma confers resistance to experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1641–1646. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gran B, Zhang GX, Yu S, Li J, Chen XH, Ventura ES, et al. IL-12p35-deficient mice are susceptible to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: evidence for redundancy in the IL-12 system in the induction of central nervous system autoimmune demyelination. J Immunol. 2002;169:7104–7110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.7104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromnes IM, Cerretti LM, Liggitt D, Harris RA, Goverman JM. Differential regulation of central nervous system autoimmunity by T(H)1 and T(H)17 cells. Nat Med. 2008;14:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nm1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager A, Dardalhon V, Sobel RA, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. Th1, Th17, and Th9 effector cells induce experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with different pathological phenotypes. J Immunol. 2009;183:7169–7177. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor RA, Prendergast CT, Sabatos CA, Lau CW, Leech MD, Wraith DC, et al. Cutting edge: Th1 cells facilitate the entry of Th17 cells to the central nervous system during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;181:3750–3754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell RC, Jong BA, Boniface K, Voort LF, Bhat R, Sarno P, et al. T helper type 1 and 17 cells determine efficacy of interferon-beta in multiple sclerosis and experimental encephalomyelitis. Nat Med. 2010;16:406–412. doi: 10.1038/nm.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea JJ, Steward-Tharp SM, Laurence A, Watford WT, Wei L, Adamson AS, et al. Signal transduction and Th17 cell differentiation. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:599–611. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C. TH17 cells in development: an updated view of their molecular identity and genetic programming. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:337–348. doi: 10.1038/nri2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miossec P, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Interleukin-17 and type 17 helper T cells. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:888–898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang W, Kolls JK, Zheng Y. The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity. 2008;28:454–467. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CT, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, Harrington LE. IL-17 family cytokines and the expanding diversity of effector T cell lineages. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CT, Hatton RD. Interplay between the TH17 and TReg cell lineages: a (co-)evolutionary perspective. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:883–889. doi: 10.1038/nri2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffen SL. Structure and signalling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:556–567. doi: 10.1038/nri2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hymowitz SG, Filvaroff EH, Yin JP, Lee J, Cai L, Risser P, et al. IL-17s adopt a cystine knot fold: structure and activity of a novel cytokine, IL-17F, and implications for receptor binding. EMBO J. 2001;20:5332–5341. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH, Dong C. IL-17F: regulation, signaling and function in inflammation. Cytokine. 2009;46:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright JF, Bennett F, Li B, Brooks J, Luxenberg DP, Whitters MJ, et al. The human IL-17F/IL-17A heterodimeric cytokine signals through the IL-17RA/IL-17RC receptor complex. J Immunol. 2008;181:2799–2805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolls JK, Linden A. Interleukin-17 family members and inflammation. Immunity. 2004;21:467–476. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley TA, Haudenschild DR, Rose L, Reddi AH. Interleukin-17 family and IL-17 receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:155–174. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YH, Liu YJ. The IL-17 cytokine family and their role in allergic inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely LK, Fischer S, Garcia KC. Structural basis of receptor sharing by interleukin 17 cytokines. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1245–1251. doi: 10.1038/ni.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, Stocking KL, Schurr J, Schwarzenberger P, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happel KI, Dubin PJ, Zheng M, Ghilardi N, Lockhart C, Quinton LJ, et al. Divergent roles of IL-23 and IL-12 in host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Exp Med. 2005;202:761–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, Stocum E, Sun JN, Lindemann MJ, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:299–311. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, Schwarzenberger P. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:624–631. doi: 10.1086/422329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MN, Kolls JK, Happel K, Schwartzman JD, Schwarzenberger P, Combe C, et al. Interleukin-17/interleukin-17 receptor-mediated signaling is important for generation of an optimal polymorphonuclear response against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect Immun. 2005;73:617–621. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.617-621.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Ritchea S, Logar A, Slight S, Messmer M, Rangel-Moreno J, et al. Interleukin-17 is required for T helper 1 cell immunity and host resistance to the intracellular pathogen Francisella tularensis. Immunity. 2009;31:799–810. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe CR, Chen K, Pociask DA, Alcorn JF, Krivich C, Enelow RI, et al. Critical role of IL-17RA in immunopathology of influenza infection. J Immunol. 2009;183:5301–5310. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiehler S, Proud D. Interleukin-17A modulates human airway epithelial responses to human rhinovirus infection. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L505–L515. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00066.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorian A, Torossian S, Demetriou M. T-cell growth, cell surface organization, and the galectin–glycoprotein lattice. Immunol Rev. 2009;230:232–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Ferguson T, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Immunogenic and tolerogenic cell death. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:353–363. doi: 10.1038/nri2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenders MI, Kolls JK, Oppers-Walgreen B, van den Bersselaar L, Joosten LA, Schurr JR, et al. Interleukin-17 receptor deficiency results in impaired synovial expression of interleukin-1 and matrix metalloproteinases 3, 9, and 13 and prevents cartilage destruction during chronic reactivated streptococcal cell wall-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3239–3247. doi: 10.1002/art.21342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JJ, Ruddy MJ, Wong GC, Sfintescu C, Baker PJ, Smith JB, et al. An essential role for IL-17 in preventing pathogen-initiated bone destruction: recruitment of neutrophils to inflamed bone requires IL-17 receptor-dependent signals. Blood. 2007;109:3794–3802. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-010116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Garcia I, Zhao Y, Ju S, Gu Q, Liu L, Kolls JK, et al. IL-17 signaling-independent central nervous system autoimmunity is negatively regulated by TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2009;182:2665–2671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiyama Y, Nakae S, Matsuki T, Nambu A, Ishigame H, Kakuta S, et al. IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:566–573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchill MA, Nardelli DT, England DM, DeCoster DJ, Christopherson JA, Callister SM, et al. Inhibition of interleukin-17 prevents the development of arthritis in vaccinated mice challenged with Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3437–3442. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3437-3442.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, Chang SH, Nurieva R, Wang YH, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Yi T, Kortylewski M, Pardoll DM, Zeng D, Yu H. IL-17 can promote tumor growth through an IL-6–Stat3 signaling pathway. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1457–1464. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryczek I, Wei S, Szeliga W, Vatan L, Zou W. Endogenous IL-17 contributes to reduced tumor growth and metastasis. Blood. 2009;114:357–359. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwandner R, Yamaguchi K, Cao Z. Requirement of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF)6 in interleukin 17 signal transduction. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1233–1240. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novatchkova M, Leibbrandt A, Werzowa J, Neubuser A, Eisenhaber F. The STIR-domain superfamily in signal transduction, development and immunity. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:226–229. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH, Park H, Dong C. Act1 adaptor protein is an immediate and essential signaling component of interleukin-17 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35603–35607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Qin J, Cui G, Naramura M, Snow EC, Ware CF, et al. Act1, a negative regulator in CD40- and BAFF-mediated B cell survival. Immunity. 2004;21:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Giltiay N, Xiao J, Wang Y, Tian J, Han S, et al. Deficiency of Act1, a critical modulator of B cell function, leads to development of Sjögren's syndrome. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2219–2228. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Liu C, Hartupee J, Altuntas CZ, Gulen MF, Jane-Wit D, et al. The adaptor Act1 is required for interleukin 17-dependent signaling associated with autoimmune and inflammatory disease. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:247–256. doi: 10.1038/ni1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin SD. IL-17 receptor signaling: ubiquitin gets in on the act. Sci Signal. 2009;2:pe64. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.292pe64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Qian W, Qian Y, Giltiay NV, Lu Y, Swaidani S, et al. Act1, a U-box E3 ubiquitin ligase for IL-17 signaling. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra63. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Kao CY, Wachi S, Thai P, Ryu J, Wu R. Requirement for both JAK-mediated PI3K signaling and ACT1/TRAF6/TAK1-dependent NF-kappaB activation by IL-17A in enhancing cytokine expression in human airway epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:6504–6513. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh A, Shan L, Halayko AJ, Kung S, Gounni AS. Critical role for STAT3 in IL-17A-mediated CCL11 expression in human airway smooth muscle cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:3357–3365. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartupee J, Liu C, Novotny M, Sun D, Li X, Hamilton TA. IL-17 signaling for mRNA stabilization does not require TNF receptor-associated factor 6. J Immunol. 2009;182:1660–1666. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemann MJ, Hu Z, Benczik M, Liu KD, Gaffen SL. Differential regulation of the IL-17 receptor by gammac cytokines: inhibitory signaling by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14100–14108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801357200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen F, Li N, Gade P, Kalvakolanu DV, Weibley T, Doble B, et al. IL-17 receptor signaling inhibits C/EBPbeta by sequential phosphorylation of the regulatory 2 domain. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst SD, Muchamuel T, Gorman DM, Gilbert JM, Clifford T, Kwan S, et al. New IL-17 family members promote Th1 or Th2 responses in the lung: in vivo function of the novel cytokine IL-25. J Immunol. 2002;169:443–453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YH, Angkasekwinai P, Lu N, Voo KS, Arima K, Hanabuchi S, et al. IL-25 augments type 2 immune responses by enhancing the expansion and functions of TSLP-DC-activated Th2 memory cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1837–1847. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angkasekwinai P, Park H, Wang YH, Chang SH, Corry DB, Liu YJ, et al. Interleukin 25 promotes the initiation of proallergic type 2 responses. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1509–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon PG, Ballantyne SJ, Mangan NE, Barlow JL, Dasvarma A, Hewett DR, et al. Identification of an interleukin (IL)-25-dependent cell population that provides IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 at the onset of helminth expulsion. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1105–1116. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owyang AM, Zaph C, Wilson EH, Guild KJ, McClanahan T, Miller HR, et al. Interleukin 25 regulates type 2 cytokine-dependent immunity and limits chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2006;203:843–849. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maezawa Y, Nakajima H, Suzuki K, Tamachi T, Ikeda K, Inoue J, et al. Involvement of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 in IL-25 receptor signaling. J Immunol. 2006;176:1013–1018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickel EA, Siegel LA, Yoon BR, Rottman JB, Kugler DG, Swart DA, et al. Identification of functional roles for both IL-17RB and IL-17RA in mediating IL-25-induced activities. J Immunol. 2008;181:4299–4310. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaidani S, Bulek K, Kang Z, Liu C, Lu Y, Yin W, et al. The critical role of epithelial-derived Act1 in IL-17- and IL-25-mediated pulmonary inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;182:1631–1640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudio E, Sonder SU, Saret S, Carvalho G, Ramalingam TR, Wynn TA, et al. The adaptor protein CIKS/Act1 is essential for IL-25-mediated allergic airway inflammation. J Immunol. 2009;182:1617–1630. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong Z, Wang A, Li Z, Ren Y, Cheng L, Li Y, et al. IL-17RD (Sef or IL-17RLM) interacts with IL-17 receptor and mediates IL-17 signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:208–215. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TS, Li XN, Chang ZJ, Fu XY, Liu L. Identification and functional characterization of a novel interleukin 17 receptor: a possible mitogenic activation through ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Cell Signal. 2006;18:1287–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Z, Altuntas CZ, Gulen MF, Liu C, Giltiay N, Qin H, et al. Astrocyte-restricted ablation of interleukin-17-induced Act1-mediated signaling ameliorates autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Immunity. 2010;32:414–425. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zheng M, Bindas J, Schwarzenberger P, Kolls JK. Critical role of IL-17 receptor signaling in acute TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:382–388. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000218764.06959.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito R, Kita M, Shin-Ya M, Kishida T, Urano A, Takada R, et al. Involvement of IL-17A in the pathogenesis of DSS-induced colitis in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor W, Jr, Kamanaka M, Booth CJ, Town T, Nakae S, Iwakura Y, et al. A protective function for interleukin 17A in T cell-mediated intestinal inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:603–609. doi: 10.1038/ni.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi A, Kuchroo VK. IL-17A directly inhibits TH1 cells and thereby suppresses development of intestinal inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:568–570. doi: 10.1038/ni0609-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]