Chemical and/or Biological Therapeutic Strategies to Ameliorate Protein Misfolding Diseases (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2012 Apr 1.

Published in final edited form as: Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010 Dec 9;23(2):231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.11.002

Abstract

Inheriting a mutant misfolding-prone protein that cannot be efficiently folded in a given cell type(s) results in a spectrum of human loss-of-function misfolding diseases. The inability of the biological protein maturation pathways to adapt to a specific misfolding-prone protein also contributes to pathology. Chemical and biological therapeutic strategies are presented that restore protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, either by enhancing the biological capacity of the proteostasis network or through small molecule stabilization of a specific misfolding-prone protein. Herein, we review the recent literature on therapeutic strategies to ameliorate protein misfolding diseases that function through either of these mechanisms, or a combination thereof, and provide our perspective on the promise of alleviating protein misfolding diseases by taking advantage of proteostasis adaptation.

Introduction

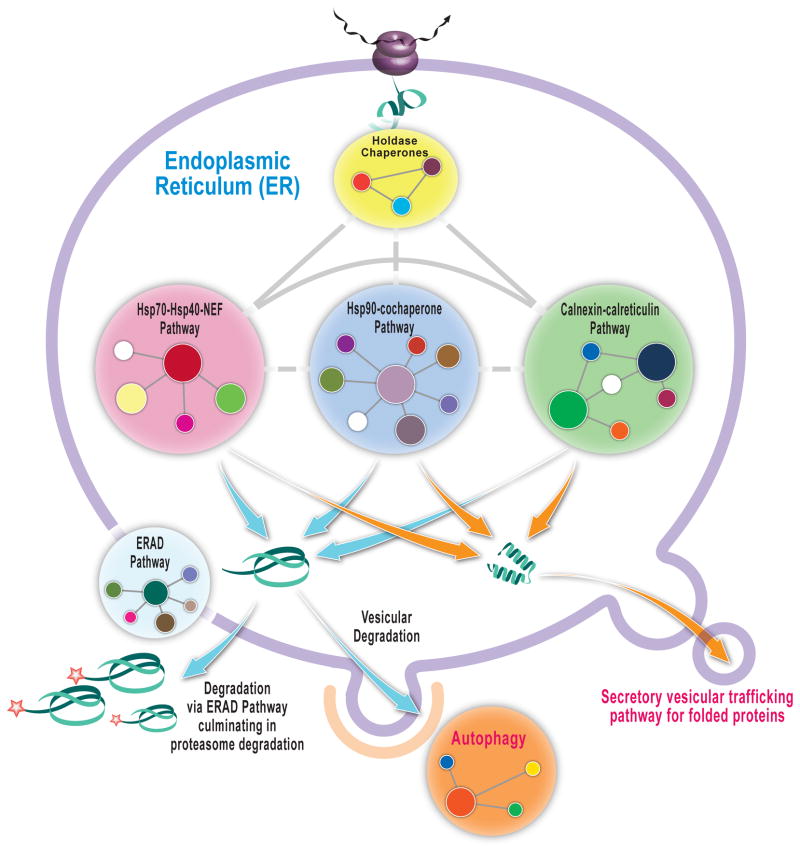

Normal physiology hinges on the quality and concentration of proteins making up an organism’s proteome. The protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, network is a highly conserved biological system designed to maintain the high quality and physiological concentration of proteins composing the proteome in spite of mutations, a constantly changing cellular and/or extracellular environment, and in the face of viral infections and other extrinsic stresses.[1,2] The proteostasis network comprises several integrated and competing biological pathways, including ribosomal protein synthesis, chaperone/co-chaperonin– and enzyme–mediated folding, proteasome- and lysosome-associated degradation pathways, vesicular trafficking pathways, etc. (Figure 1). [3–5] The proteostasis networks in each subcellular compartment have unique attributes, and are independently regulated by stress-responsive signaling pathways that attempt to match proteostasis network capacity with demand, principally by coordinated transcriptional and translational upregulation of deficient pathways [6,7]. There are also post-translational mechanisms to match proteostasis network capacity with demand [8–10].

Figure 1. The Proteostasis Network.

Schematic of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) proteostasis network in mammalian cells depicting the components and the connections in simplified format. A holdase chaperone delivers the nascent chain to the Hsp-70-40-nucleotide exchange factor pathway and/or the Hsp90-cochaperone pathway and/or the Calnexin-calreticulin pathway which can lead to folding and vesicular trafficking or degradation mediated by ER-associated degradation (proteasome) and/or by autophagy.

The competition between protein folding and degradation is a key feature of proteostasis network function (Figure 1). Mutant proteins that do not fold efficiently at a given proteostasis network capacity are largely degraded by the proteasome or by lysosomes, leading to the loss-of-function phenotype of numerous protein misfolding diseases like cystic fibrosis [11] and the lysosomal storage diseases [12].

The folding efficiency of proteins that have evolved to function in destination environments that are chemically distinct from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), such as in the lysosome which has an operating pH of 5, can be dramatically reduced by a mutation in the neutral pH environment of the ER. Many of the mutant lysosomal enzymes that cause lysosomal storage diseases (LSDs) do not fold efficiently in the ER, resulting in excessive ER-associated degradation (Figure 1) [13]. Nonetheless, if the properly folded mutant enzymes can be trafficked to the lysosome, they are actually quite stable and sufficiently active at pH 5 to degrade their substrate [14,15]. One way to increase ER folding competency is to lower the growth temperature of patient-derived fibroblasts. Lowering the growth temperature to 25 °C also makes the cytosol more folding competent, strikingly improving the folding, trafficking and function of the misfolding-prone ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) [16]. Thus, loss of function, due to excessive degradation, can be minimized by increasing the folding capacity of the proteostasis network in the compartment where it is deficient (the ER in LSDs and the cytosol in ΔF508 CFTR).

Herein, we review emerging chemical and biological approaches for improving defective proteostasis leading to the lysosomal storage diseases and cystic fibrosis. These therapeutic strategies are applicable to numerous loss-of-function diseases associated with excessive misfolding and degradation and have important implications for how medicine will likely be practiced in the future.

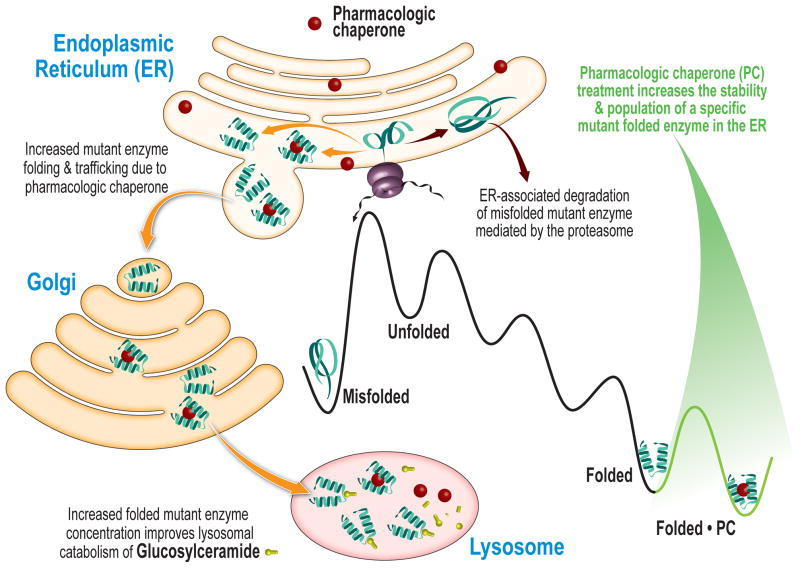

A chemical approach to stabilize and increase the folded population of a misfolding-prone protein

Pharmacologic chaperones represent a promising therapeutic strategy to ameliorate loss-of-function diseases and are currently being evaluated in clinical trials for LSDs and for cystic fibrosis. Pharmacologic chaperones are small molecules which bind to and stabilize the folded state of a specific misfolding-prone protein, thereby increasing the concentration of the folded mutant protein that can engage its trafficking receptor and proceed to its destination environment, resulting in increased function (Figure 2). Fan et al. [17] first demonstrated that a potent inhibitor of α-galactosidase A, 1-deoxy-galactonojirimycin, rescues the cellular misfolding and degradation of α-galactosidase A mutants associated with Fabry disease. Since then, pharmacologic chaperones have been developed for Gaucher’s [18] and infantile Batten diseases [19], employing patient-derived cellular models. The downside of the pharmacological chaperone approach is that a specific small molecule has to be tailored for each non-homologous protein linked to a loss-of-function misfolding disease, which number in excess of 50.

Figure 2. Pharmacologic Chaperoning.

A small molecule pharmacologic chaperone binds to the folded ensemble of a specific mutant misfolding-prone lysosomal storage disease-associated enzyme in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and stabilizes the mutant enzyme. This increases the fraction of folded enzyme that can bind to the trafficking receptor and be trafficked to the lysosome to degrade its substrate.

Biological approaches to match proteostasis network capacity with demand to ameliorate misfolding diseases

A more general therapeutic strategy to alleviate loss-of-function diseases uses proteostasis regulators, small molecules or biologics (e.g., siRNA) that enhance proteostasis network capacity in the deficient compartment [1]. Proteostasis regulators can function through many different mechanisms, including activation of unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling, whereby hundreds of ER proteostasis network proteins are upregulated in a coordinated fashion through a transcriptional program [6,7]. Proteostasis regulators can also enhance proteostasis capacity through post-translational and epigenetic mechanisms [8,9,20].

Proteostasis regulators upregulate proteostasis network capacity

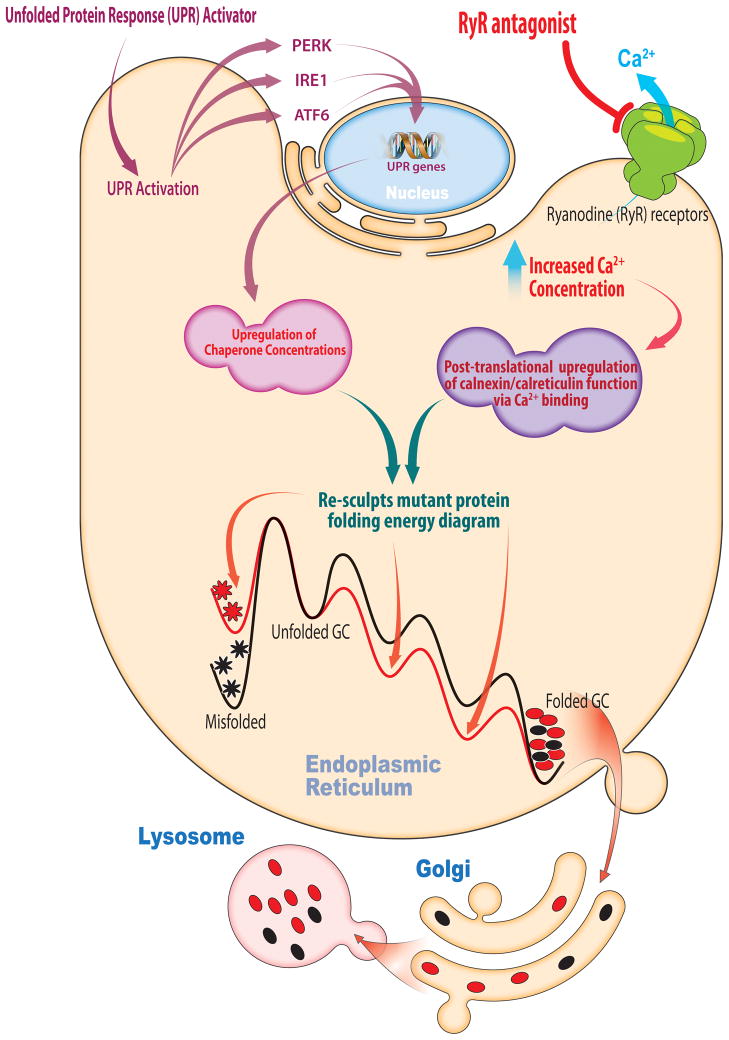

Celastrol is a proteostasis regulator that enhances ER proteostasis capacity by inducing all three arms of the UPR [21]. Treatment of Gaucher’s patient-derived fibroblasts with celastrol demonstrated that the IRE1-XBP and PERK arms of the UPR appear to be functionally important for enhancing mutant enzyme proteostasis [21]. This strategy also increases the efficiency of folding, trafficking and function of nonhomologous enzymes associated with a spectrum of LSDs [21]. That the IRE1-XBP arm is important in LSDs was expected, since this is the only arm of the UPR that is conserved across eukaryotes [6,7]. Stress-responsive UPR signaling increases chaperone and folding enzyme levels in the ER, which resculpts the mutant enzyme’s folding free energy diagram “pushing” more protein toward the folded state at the expense of mutant enzyme misfolding, degradation and aggregation (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Adapting the Proteostasis Network.

Small molecule proteostasis regulators can induce the unfolded protein response (UPR) transcriptional program leading to the coordinated upregulation of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) proteostasis network capacity. The chaperones, co-chaperones and folding enzymes can resculpt the folding free energy diagram of mutant enzymes, “pushing” more protein toward the native state by lowering the energy of intermediate and transition states and minimizing misfolding. Small molecule proteostasis regulators can also function by post-translation regulation mechanisms. One example are the Ryanodine receptor antagonists that increase the ER Ca2+ concentration leading to more Ca2+ binding by the chaperones, including calnexin and calreticulin, increasing their activity and ability to resculpt the folding free energy diagram of mutant lysosomal enzymes by “pushing” more protein toward the native state at the expense of misfolding.

The second class of proteostasis regulators increase ER Ca2+ levels. These small zolecules function by inhibition of ryanodine receptor Ca2+ efflux channels in the ER membrane (Figure 3) [9] and probably L-type Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane [8]. Increased ER Ca2+ levels appear to upregulate the chaperoning capacity of calnexin (and likely other Ca2+-regulated ER chaperones) through Ca2+ binding, without increasing chaperone concentrations. Enhanced chaperone activity resculpts folding free energy diagrams, increasing the population of folded mutant lysosomal enzymes that are capable of engaging their trafficking receptors, at the expense of ERAD (Figure 3) [9].

Chaperone activity is also critical for CFTR proteostasis, since siRNA depletion of the Hsp90 co-chaperone, Aha1, partially restores the folding, trafficking and Cl− conductance of ΔF508 CFTR. In this case, cytosolic chaperones are critical because the misfolding-prone nucleotide binding domain I is in the cytosol. Presumably, the Hsp90 ATPase cycle was slowed to match the slowed folding kinetics of the cytosolic domain harboring the ΔF508 mutation, although other mechanisms are possible [22,23].

Consistent with cytosol proteostasis being important, Marozkina et al. [24] found that the signaling molecule S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) enhances ΔF508 CFTR proteostasis by S-nitrosylating the Hsp70/Hsp90 organizing protein, Hop. GSNO decreased the Hop concentration, decreasing Hop binding to CFTR that leads to degradation. Cell growth at a permissive temperature in the presence of GSNO exhibited a synergistic rescue of ΔF508 CFTR proteostasis, consistent with combined approaches that are mechanistically distinct.

Proteostasis regulators that influence intracellular trafficking pathways

Upregulating a misfolding-prone protein’s specific trafficking receptor can also restore proteostasis, as demonstrated in a Gaucher’s disease cellular model. Overexpression of LIMP-2, the glucocerebrosidase trafficking receptor [25], in COS7 cells was sufficient to restore the lysosomal localization of L444P glucocerebrosidase, a severe neuropathic Gaucher’s disease mutant. Thus, small molecules that upregulate LIMP-2 expression levels may function as proteostasis regulators for Gaucher’s disease. Similarly, overexpression of the mannose-6-phosphate receptor used by other LSD-associated enzymes to get to the lysosome may also prove useful for ameliorating other LSDs.

Regulating intracellular vesicular trafficking can also influence lysosomal enzyme proteostasis. Reducing intracellular cholesterol levels in Gaucher’s patient-derived fibroblasts improved mutant glucocerebrosidase trafficking and function [26]. This observation and reports of autophagic defects in the lysosomal storage diseases [27–30] support the idea that manipulating the intracellular vesicular trafficking pathways offers value for treating these diseases. An activity-based screen identified ubiquitin specific protease-10 (USP-10), a deubiquitinating enzyme of ΔF508 CFTR, as a potential therapeutic target for cystic fibrosis [31]. USP-10 is localized in early endosomes and regulates the post-endocytic sorting of CFTR. Overexpressing USP-10 decreased the amount of ubiquitinated CFTR and increased its abundance in the plasma membrane of human airway epithelial cells [31].

Proteostasis regulators that influence protein degradation decisions

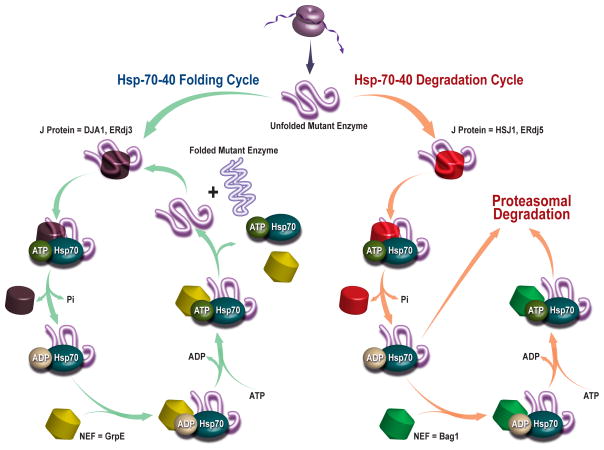

Since competition between protein folding and degradation is a key feature of maintaining proteostasis, proteostasis regulators that enhance folding and trafficking at the expense of degradation offer promising therapeutic strategies. For instance, antagonizing the Hsp70–40 degradation pathway or activating the Hsp70–40 folding pathway is expected to rescue misfolding- and degradation-prone proteins (Figure 4). Park et al. [32] demonstrated that a soluble sulfogalactosyl ceramide mimic selectively inhibited Hsp40-activated Hsc70 ATP hydrolysis, reducing Hsc70 chaperone function. This increases the immature form (band b) of ΔF508 CFTR, suggesting increased escape from ERAD, leading to increased maturation and iodide efflux from ΔF508 CFTR in transfected BHK cells. Similarly, Schmidt et al. [33] found that a J-domain containing protein, the cysteine string protein (Csp), inhibited CFTR ER exit and facilitated its degradation. Overexpression of Csp enhanced CFTR-Hsc70 and CFTR-CHIP interactions, promoting CFTR ubiquitination and degradation, suggesting that antagonizing these interactions is a possible therapeutic strategy.

Figure 4. Competition between Protein Folding and Degradation is a Central Feature of Proteostasis Network Function.

Depicted is an Hsp-70-40-nucleotide exchange proteostasis pathway that is intentionally generic (not organelle specific), illustrating how the competition between folding and degradation of a foldable protein is affected. As can be discerned from this representative pathway, the concentrations and activity of many components (many not shown) influence the ratio of folding to degradation for a particular client protein.

Interfering with the ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation process is yet another means to counter extensive protein degradation in favor of folding, trafficking and function. Hassink et al. [34] showed that an ER-resident transmembrane deubiquitinating enzyme, ubiquitin specific protease (USP)-19, rescues ΔF508 CFTR from proteasomal degradation. USP-19 is a UPR-regulated deubiquitinating enzyme which appears to be involved in a late step of protein quality control, by rescuing ERAD substrates that have been retrotranslocated to the cytosol. Tcherpakov et al. [35] found that the ER ubiquitin ligase, RNF5, associates with and ubiquitinates the JNK-associated membrane protein (JAMP). JAMP ubiquitination inhibits its association with the Rpt5 ATPase and p97, leading to an inefficient clearance of ΔF508 CFTR, suggesting an opportunity could exist for enhancing CFTR proteostasis. Consistent with this hypothesis, Ye et al. [36] demonstrated that the siRNA knockdown of c-Cbl, a multifunctional protein with ubiquitin ligase activity and protein adaptor function, increased CFTR surface expression and CFTR-mediated Cl− function. c-Cbl first facilitates CFTR endocytosis by a ubiquitin-independent mechanism, and subsequently ubiquitinates CFTR in early endosomes, promoting CFTR lysosomal degradation in human airway epithelial cells.

Degradation of CFTR can also occur as a consequence of proteostasis network decisions made in the Golgi. Cheng et al. [37] found that silencing the SNARE protein, STX6, increases both wild type and ΔF508 CFTR protein levels and Cl- ion channel function. STX6 interacts with the PDZ domain containing protein CAL that is localized to the Golgi and in Golgi-derived vesicles. The effect of STX6 on CFTR proteostasis and function is dependent on CAL. Interestingly, silencing STX6 enhances the low temperature effect in rescuing ΔF508 CFTR, which again suggests the utility of combining mechanistically distinct therapeutic strategies for cystic fibrosis treatment.

Recent elegant work from Okiyoneda et al. [38], using siRNA-mediated functional screens, takes advantage of the fact that the ΔF508 CFTR is degraded from the plasma membrane when shifted from 26°C to 37°C. They identified chaperones, co-chaperones, and ubiquitin-conjugating and –ligating enzymes (that make up “the CFTR peripheral protein quality control system”) that eliminate unfolded CFTR from the cell surface. An unanticipated finding was that several cytosolic proteins, including the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UbcH5, the ubiquitin ligase CHIP, and Hsp70/Hsp90 proteins that influence CFTR proteostasis during nascent protein synthesis, also play similar roles at the plasma membrane or in the peripheral protein quality control system. This observation suggests that the fate of proteins throughout their functional life cycle is influenced by members of proteostasis network whose effect may not be easily anticipated.

Proteostasis regulators that impact proteostasis at the genomic and epigenomic levels

A novel strategy to restore proteostasis comes from a study by Sardiello et al. [39], who discovered that the transcription factor EB coordinates the transcriptional behavior of most lysosomal genes. Overexpression of EB in cultured cells upregulated lysosomal genes and genes related to lysosomal biogenesis and function. This finding underlines the therapeutic potential of small molecule transcription factor activators that regulate lysosomal genes for treating multiple lysosomal storage diseases.

Manipulating the proteostasis network at the epigenetic level is another promising approach for treating loss-of-function diseases. Hutt et al. [20] demonstrated that reducing the activities of histone deacetylases (HDACs), in particular HDAC7, using suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid or siRNA, partially restored the surface channel activity of the ΔF508 CFTR in human primary airway epithelia. Reducing HDAC7 activity increased mRNA levels encoding the CFTR interactome, suggesting that epigenetic upregulation of the CFTR proteostasis network is responsible for the increased CFTR Cl− channel activity. It is anticipated that epigenetic manipulation of the proteostasis network will ameliorate other loss-of-function diseases.

Combining pharmacologic chaperones and proteostasis regulators yields a synergistic rescue of proteostasis

Because pharmacologic chaperones increase the population of the folded state by direct binding and stabilization (“pulling protein toward the folded state”), whereas proteostasis regulators increase the folded state population by upregulating the proteostasis network which resculpts the folding free energy diagram of the mutant enzyme (“pushing protein toward the folded state”), it is not surprising that combination of a proteostasis regulator and a pharmacologic chaperone synergize to rescue mutant enzyme folding, trafficking and function in LSDs. Mu et al. [21] showed that treatment of Gaucher’s fibroblasts harboring the L444P glucocerebrosidase mutant with the pharmacologic chaperone, NN-DNJ, and a proteostasis regulator, MG-132 or celastrol, resulted in a 4–6 fold increase in the lysosomal enzyme activity, greater than the sum of the effect with each compound alone. L444P glucocerebrosidase is usually not amenable to pharmacologic chaperoning because of the very low steady state concentration of the folded state that exists in patient-derived fibroblasts. Proteostasis regulators increase the folded state population of L444P glucocerebrosidase and that, in turn, renders pharmacologic chaperones more efficacious. A similar synergistic rescue of lysosomal enzyme proteostasis is predicted when two mechanistically distinct proteostasis regulators are co-applied to cells.

Conclusions and perspective

Adapting the proteostasis network, by utilizing small molecules or RNAi, has emerged as a promising strategy to treat a wide variety of loss-of-function diseases. The concern that increasing proteostasis network capacity will increase the concentration of much of the proteome maturing in that compartment is an important one. However, quantitative whole cell proteomics carried out on proteostasis regulator-treated cells reveal that the vast majority of the proteome remains unchanged because it exhibits sufficiently fast folding, high enough thermodynamic stability, and slow enough misfolding or aggregation kinetics to fold very efficiently at the basal level of proteostasis network capacity [21]. The ability of proteostasis regulators to resculpt the folding free energy diagram of mutant proteins enables one proteostasis regulator to be used for multiple misfolding diseases, assuming that the mutant proteins depend on common proteostasis network components. This transforms the economics of drug development for rare diseases; for example, numerous lysosomal storage diseases can in principle be treated with a single proteostasis regulator that upregulates proteostasis network components capable of folding many of the LSD-associated mutant enzymes. Moreover, the synergistic effect realized by combining two mechanistically distinct proteostasis regulators, or a proteostasis regulator and a pharmacologic chaperone, suggests that misfolding diseases will be treated in the future with at least two agents capable of restoring proteostasis through distinct mechanisms of action.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Colleen Fearns for critical feedback on this review. This work was supported by the NIH (DK75295), the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, and the Lita Annenberg Hazen Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and recommended reading

Particular papers of interest have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- **1.Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. Review describing the proteostasis network, how deficiencies in proteostasis results in various human diseases, and the utility of proteostasis regulators to manipulate the concentration, conformation, quaternary structure, and/or location of the protein(s) to ameliorate these diseases. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powers ET, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW, Balch WE. Biological and Chemical Approaches to Diseases of Proteostasis Deficiency. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:23.21–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.114844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deuerling E, Bukau B. Chaperone-assisted folding of newly synthesized proteins in the cytosol. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:261–277. doi: 10.1080/10409230490892496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang YC, Chang HC, Chakraborty K, Hartl FU, Hayer-Hartl M. Essential role of the chaperonin folding compartment in vivo. EMBO J. 2008;27:1458–1468. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bukau B, Weissman J, Horwich A. Molecular chaperones and protein quality control. Cell. 2006;125:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:739–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *8.Mu TW, Fowler DM, Kelly JW. Partial restoration of mutant enzyme homeostasis in three distinct lysosomal storage disease cell lines by altering calcium homeostasis. PloS Biol. 2008;6:253–265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060026. This paper reveals the potential utility of a single small molecule proteostasis regulator to ameliorate multiple lysosomal storage diseases that are associated with non-homologous lysosomal proteins. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ong DST, Mu TW, Palmer AE, Kelly JW. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ increases enhance mutant glucocerebrosidase proteostasis. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:424–432. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westerheide SD, Anckar J, Stevens SM, Jr, Sistonen L, Morimoto RI. Stress-inducible regulation of heat shock factor 1 by the deacetylase SIRT1. Science. 2009;323:1063–1066. doi: 10.1126/science.1165946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosser MFN, Grove DE, Cry DM. The use of small molecules to correct defects in CFTR folding, maturation, and channel activity. Current Chemical Biology. 2009;3:420–431. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Futerman AH, van Meer G. The cell biology of lysosomal storage disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:554–565. doi: 10.1038/nrm1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sawkar AR, D'Haeze W, Kelly JW. Therapeutic strategies to ameliorate lysosomal storage disorders - a focus on Gaucher disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1179–1192. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5437-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawkar AR, Schmitz M, Zimmer KP, Reczek D, Edmunds T, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Chemical chaperones and permissive temperatures atter the cellular locatization of Gaucher disease associated glucocerebrosidase variants. ACS Chem Biol. 2006;1:235–251. doi: 10.1021/cb600187q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan JQ. A counterintuitive approach to treat enzyme deficiencies: use of enzyme inhibitors for restoring mutant enzyme activity. Biol Chem. 2008;389:1–11. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denning GM, Anderson MP, Amara JF, Marshall J, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Processing of mutant cystic-fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is temperature-sensitive. Nature. 1992;358:761–764. doi: 10.1038/358761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *17.Fan JQ, Ishii S, Asano N, Suzuki Y. Accelerated transport and maturation of lysosomal alpha-galactosidase A in Fabry lymphoblasts by an enzyme inhibitor. Nat Med. 1999;5:112–115. doi: 10.1038/4801. This pioneering paper established the concept of pharmacologic chaperoning. The authors demonstrated that a competitive enzyme inhibitor, 1-deoxy-galactonojirimycin, effectively enhanced mutant alpha-Gal A enzyme activity in Fabry lynphoblasts and in some organs of a transgenic mouse model overexpressing a mutant alpha-Gal A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawkar AR, Cheng WC, Beutler E, Wong CH, Balch WE, Kelly JW. Chemical chaperones increase the cellular activity of N370S beta-glucosidase: A therapeutic strategy for Gaucher disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2002;99:15428–15433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192582899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dawson G, Schroeder C, Dawson PE. Palmitoyl:protein thioesterase (PPT1) inhibitors can act as pharmacological chaperones in infantile Batten disease. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2010;395:66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.03.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *20.Hutt DM, Herman D, Rodrigues APC, Noel S, Pilewski JM, Matteson J, Hoch B, Kellner W, Kelly JW, Schmidt A, et al. Reduced histone deacetylase 7 activity restores function to misfolded CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:25–33. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.275. This paper lends support to the use of epigenetic-based proteostasis regulators in treating loss-of-function diseases. In this case, reducing histone deacetylase 7 activity has profound effect on the folding and activity of the ΔF508 CFTR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *21.Mu TW, Ong DST, Wang YJ, Balch WE, Yates JR, Segatori L, Kelly JW. Chemical and biological approaches synergize to ameliorate protein-folding diseases. Cell. 2008;134:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.037. This paper demonstrated that activation of the unfolded protein response can lead to a meaningful physiologic outcome–partial restoration of mutant lysosomal enzyme proteostasis by upregulating the ER folding capacity. This paper also demonstrated the synergy that is realized when a proteostasis regulator and a pharmacologic chaperone are used together to alleviate lysosomal storage diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *22.Wang XD, Venable J, LaPointe P, Hutt DM, Koulov AV, Coppinger J, Gurkan C, Kellner W, Matteson J, Plutner H, et al. Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1 downregulation rescues misfolding of CFTR in cystic fibrosis. Cell. 2006;127:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.043. This paper illustrates how the folding-vs-degradation decision is made by the cytosolic proteostasis network operating on ΔF508 CFTR. In particular, this decison can be influenced by decreasing the level of the Hsp90 cochaperone Aha1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koulov AV, LaPointe P, Lu BW, Razvi A, Coppinger J, Dong MQ, Matteson J, Laister R, Arrowsmith C, Yates JR, et al. Biological and Structural Basis for Aha1 Regulation of Hsp90 ATPase Activity in Maintaining Proteostasis in the Human Disease Cystic Fibrosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:871–884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-12-1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marozkina NV, Yemen S, Borowitz M, Liu L, Plapp M, Sun F, Islam R, Erdmann-Gilmore P, Townsend RR, Lichti CF, et al. Hsp 70/Hsp 90 organizing protein as a nitrosylation target in cystic fibrosis therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2010;107:11393–11398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909128107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Reczek D, Schwake M, Schroder J, Hughes H, Blanz J, Jin XY, Brondyk W, Van Patten S, Edmunds T, Saftig P. LIMP-2 is a receptor for lysosomal mannose-6-phosphate-independent targeting of beta-Glucocerebrosidase. Cell. 2007;131:770–783. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.018. This paper introduces the hypothesis that increasing the concentration of trafficking receptors has the potential to correct defective mutant enzyme proteostasis. Here, the identification of the glucocerebrosidase trafficking receptor, LIMP-2, led to the observation that LIMP-2 overexpression improves the lysosomal trafficking of some mutant glucocerebrosidase enzymes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ron I, Horowitz M. Intracellular cholesterol modifies the ERAD of glucocerebrosidase in Gaucher disease patients. Mol Gen Metab. 2008;93:426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.10.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Settembre C, Fraldi A, Jahreiss L, Spampanato C, Venturi C, Medina D, de Pablo R, Tacchetti C, Rubinsztein DC, Ballabio A. A block of autophagy in lysosomal storage disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:119–129. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vergarajauregui S, Connelly PS, Daniels MP, Puertollano R. Autophagic dysfunction in mucolipidosis type IV patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2723–2737. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raben N, Hill V, Shea L, Takikita S, Baum R, Mizushima N, Ralston E, Plotz P. Suppression of autophagy in skeletal muscle uncovers the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and their potential role in muscle damage in Pompe disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3897–3908. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chevrier M, Brakch N, Lesueur C, Genty D, Ramdani Y, Moll S, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Brasse-Lagnel C, Laquerriere A, Barbey F, et al. Autophagosome maturation is impaired in Fabry disease. Autophagy. 2010;6:589–599. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.5.11943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bomberger JM, Barnaby RL, Stanton BA. The Deubiquitinating Enzyme USP10 Regulates the Post-endocytic Sorting of Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator in Airway Epithelial Cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18778–18789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.001685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park HJ, Mylvaganum M, McPherson A, Fewell SW, Brodsky JL, Lingwood CA. A Soluble Sulfogalactosyl Ceramide Mimic Promotes Delta F508 CFTR Escape from Endoplasmic Reticulum Associated Degradation. Chem Biol. 2009;16:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt BZ, Watts RJ, Aridor M, Frizzell RA. Cysteine String Protein Promotes Proteasomal Degradation of the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) by Increasing Its Interaction with the C Terminus of Hsp70-interacting Protein and Promoting CFTR Ubiquitylation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4168–4178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806485200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hassink GC, Zhao B, Sompallae R, Altun M, Gastaldello S, Zinin NV, Masucci MG, Lindsten K. The ER-resident ubiquitin-specific protease 19 participates in the UPR and rescues ERAD substrates. EMBO Reports. 2009;10:755–761. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tcherpakov M, Delaunay A, Toth J, Kadoya T, Petroski MD, Ronai ZA. Regulation of Endoplasmic Reticulum-associated Degradation by RNF5-dependent Ubiquitination of JNK-associated Membrane Protein (JAMP) J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12099–12109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808222200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye SY, Cihil K, Stolz DB, Pilewski JM, Stanton BA, Swiatecka-Urban A. c-Cbl Facilitates Endocytosis and Lysosomal Degradation of Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator in Human Airway Epithelial Cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27008–27018. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng J, Cebotaru V, Cebotaru L, Guggino WB. Syntaxin 6 and CAL Mediate the Degradation of the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1178–1187. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **38.Okiyoneda T, Barriere H, Bagdany M, Rabeh WM, Du K, Hohfeld J, Young JC, Lukacs GL. Peripheral Protein Quality Control Removes Unfolded CFTR from the Plasma Membrane. Science. 2010;329:805–810. doi: 10.1126/science.1191542. This paper suggests that proteins that are part of the CFTR cytosolic proteostasis network also play a similar role in the peripheral protein quality control system. Thus, the proteostasis networks in different subcellular compartments cooperate to maintain protein homeostasis through unknown regulatory mechanisms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sardiello M, Palmieri M, di Ronza A, Medina DL, Valenza M, Gennarino VA, Di Malta C, Donaudy F, Embrione V, Polishchuk RS, et al. A Gene Network Regulating Lysosomal Biogenesis and Function. Science. 2009;325:473–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1174447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]