Neprilysin-2 Is an Important β-Amyloid Degrading Enzyme (original) (raw)

Abstract

Proteases that degrade the amyloid-β peptide (Aβ) are important in protecting against Alzheimer's disease (AD), and understanding these proteases is critical to understanding AD pathology. Endopeptidases sensitive to inhibition by thiorphan and phosphoramidon are especially important, because these inhibitors induce dramatic Aβ accumulation (∼30- to 50-fold) and pathological deposition in rodents. The Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin (NEP) is the best known target of these inhibitors. However, genetic ablation of NEP results in only modest increases (∼1.5- to 2-fold) in Aβ, indicating that other thiorphan/phosphoramidon-sensitive endopeptidases are at work. Of particular interest is the NEP homolog neprilysin 2 (NEP2), which is thiorphan/phosphoramidon-sensitive and degrades Aβ. We investigated the role of NEP2 in Aβ degradation in vivo through the use of gene knockout and transgenic mice. Mice deficient for the NEP2 gene showed significant elevations in total Aβ species in the hippocampus and brainstem/diencephalon (∼1.5-fold). Increases in Aβ accumulation were more dramatic in NEP2 knockout mice crossbred with APP transgenic mice. In NEP/NEP2 double-knockout mice, Aβ levels were marginally increased (∼1.5- to 2-fold), compared with NEP−/−/NEP2+/+ controls. Treatment of these double-knockout mice with phosphoramidon resulted in elevations of Aβ, suggesting that yet other NEP-like Aβ-degrading endopeptidases are contributing to Aβ catabolism.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder currently affecting more than 26 million people worldwide and, as advances in modern medicine prolong lifespan, this number is expected to quadruple by 2050.1 A major factor believed to be involved in the progression of AD pathology is the accumulation of amyloid-β peptide (Aβ). Studying the mechanisms of Aβ clearance is, therefore, very important to understanding AD.

Currently, enzymatic degradation is thought to play an integral role in the removal of Aβ. Of the Aβ-degrading enzymes, neprilysin (NEP) has been shown to be highly critical for cerebral Aβ control.2 NEP expression has also been inversely correlated with amyloid pathology in humans and mice, and NEP gene transfer has been reported to reduce amyloid pathology in transgenic mice (reviewed by Marr and Spencer3). Despite the importance of NEP-mediated Aβ degradation, NEP knockout (KO) mice show only moderately elevated Aβ levels (1.5- to 2-fold), insufficient to cause plaque deposition.4 However, when treated with thiorphan, an NEP endopeptidase inhibitor, mice and rats demonstrate pathological accumulations of Aβ after only 1 month.2,5 This was also found in mice treated with phosphoramidon, another NEP inhibitor.6 These results indicate that there may exist additional NEP-like endopeptidases in the metalloprotease 13 (M13) family that are central to the Aβ clearance pathway.

The NEP homolog neprilysin 2 (NEP2) is one such endopeptidase. NEP2 (also known as MMEL1/2, SEP, NL1, NEPLP) possesses a 55% sequence identity to NEP and has been shown to degrade vasoactive peptides.7,8 In addition, the membrane-bound α-splice form of murine NEP2 has demonstrated Aβ-degrading properties in membrane fractions.9 In transduced HEK293T cells, our research group previously showed that cell surface human NEP2 (β-splice form) was able to degrade both Aβ42 and Aβ40 peptides.10 Subcellular localization studies using transfection into CHO cells have found that murine NEP2 is present primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum.7,11 However, Oh-Hashi and colleagues12 did find murine NEP2 activity at the cell surface. Studies of NEP2 in mice and rats have demonstrated that it is expressed primarily neurons and shows mild expression in the cerebral cortex, mild to moderate expression in the hippocampus, and strong expression in numerous thalamic, hypothalamic, and brainstem nuclei.13–15 In mice, however, expression in the hippocampus could not be confirmed, because of high background levels.15 NEP2 is involved in sperm function in mice and modulates fertilization and early embryonic development.16 However, NEP2 also functions as a neuropeptidase, one that is possibly involved in several physiological pathways controlling nociception, energy, and endocrine functions.15,17,18

The purpose of this study was to investigate the in vivo role of NEP2 in Aβ degradation in mice. Using NEP2 KO16 and NEP/NEP2 double-knockout (DKO) mice, the importance of NEP2 was investigated by measuring Aβ levels in various regions in the brain of KO and control mice. In addition, APP transgenic mice crossed with NEP2 KO mice were used to test the effect of NEP2 on Aβ removal when challenged with high Aβ levels. Defining the role of NEP2 in Aβ clearance will provide further insight into AD pathogenesis and possible therapies for this disease.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All mice were used according to institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols and in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as published in 1996 by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. NEP2 (Mme/1) KO mice16 were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. Luc DesGroseillers. NEP/NEP2 DKO mice were created by cross-breeding NEP2 KO mice (129 background) with NEP (Mme) KO mice (BALB/c background) (received from the laboratory of Dr. Bao Lu).19 These mice were backcrossed once more with the NEP KO mice (BALB/c background) before being maintained by inbreeding NEP−/−/NEP2+/+ or NEP−/−/NEP2−/− strains. APPtg/NEP2 KO mice were created by cross-breeding NEP2 KO mice (129 background) with APPtg mice (TASD41 line, received from the laboratory of Dr. Eliezer Masliah) (Blk/Sw background).20 These mice are propagated by breeding heterozygous APP transgenic mice having either wild-type or NEP2−/− backgrounds with wild-type (129) or NEP2−/− (129) mice, respectively. The analysis was done with mice that had been backcrossed three times with the 129 lines.

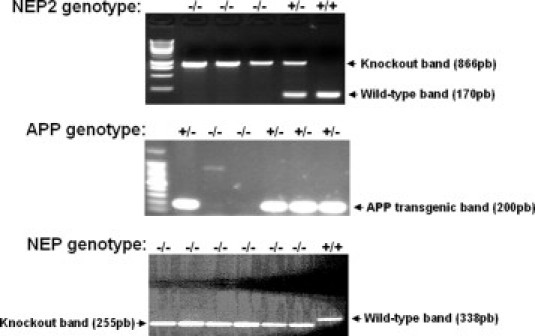

Mouse genotypes were confirmed by PCR analysis. Briefly, NEP2 gene knockout mice were identified using a specific primer set (wt-F: 5′-TGGAACTGGAGACGCATCTGG-3′, Neo-F: 5′-TCCTGTCATCTCACCTGGCTCC-3′, NL1-R: 5′-TAGCTCCATCAGGTCCATTCG-3′): APPtg mice were identified by using a specific primer pair (APPtg-F: 5′-GGCTACGAAAATCCAACCTACAAG-3′, APPtg-R: 5′-GATGATGGCATGCAGCACTGG-3′); and NEP KO mice were identified using a specific primer set (Exon12-F: 5′-GAAATCATGTCAACTGTG-3′, Neo-R: 5′-ATCAGAAGCTTATCGAT-3′, Exon13-R: 5′-CTTGCGGAAAGCATTTC-3′). Examples of PCR genotyping results are presented in Supplemental Figure S1 (at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Aβ Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Mice were anesthetized with 2-bromo-2-chloro-1,1,1-trifluoroethane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and were sacrificed by cervical dislocation for Aβ analysis. Brains were extracted and dissected into four regions: cerebellum, brainstem/diencephalon, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex. Samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Frozen brain sections were homogenized in lysis buffer (5 mol/L guanidine HCl; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) using a Polytron homogenizer (Kinematica, Bohemia, NY). Quantification of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 was performed using isoform-specific Aβ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA).4 Statistics were determined using two-tailed Student's _t_-test compared with control.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse hemibrains were placed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Fisher Scientific) fixative for 24 hours before storage in a cryoprotectant solution (30% sucrose, 0.1 mol/L PO4). Fixed hemibrains were sagittally sectioned on a freezing microtome (40 μm) and stored in a cryoprotectant solution at −20°C. Every sixth brain slice was selected for pretreatment with 70% formic acid for 10 minutes. After application of the primary antibody (4G8, 1:1500, Sigma-Aldrich), samples were incubated for 48 hours at 4°C before applying secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse 1:250, or Alexa Fluor-594 goat anti-mouse 1:250; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and were imaged by fluorescent microscopy (Microscopy and Imaging Facility, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, IL). Aβ plaque burden was quantified by averaging the percent area staining positive (above threshold) within the entire specified brain region from several sections per animal, using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Intracellular Aβ was also measured by averaging the percent area staining positive (excluding plaques) in the cortex or in the CA fields of the hippocampus.21 Statistics were determined using two-tailed Student's _t_-test compared with control.

In Vitro Aβ Degradation Assay

The murine NEP2α cDNA construct was generated by PCR mutagenesis (as previously described)22 of the murine NEP2β cDNA, to delete the alternative exon missing in murine NEP2α.10 Sequencing analysis confirmed the correct deletion (Northwestern Genomics Core Facility, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL). For the assay, conditioned medium containing Aβ was first collected from supernatants of HEK293T cells transfected with a mutant APP expression plasmid, as previously described.23 HEK293T cells were then transfected (calcium-phosphate method)24 with expression plasmids for murine NEP2α, human NEP, or green fluorescent protein (GFP). Two days after transfection, cell medium was replaced with conditioned medium containing Aβ42 (50 pmol/L) with or without 100 μmol/L thiorphan (T). After 5 hours of incubation at 37°C (10% CO2), supernatants were collected, centrifuged to remove cell debris (1000 × g, 5 minutes), and quantified using Aβ ELISA (as described above). Statistics were determined using two-tailed Student's _t_-test compared with control (GFP).

Intracerebroventricular Infusion of Phosphoramidon

Mice (NEP/NEP2 DKO) were anesthetized using isoflurane and placed on a stereotaxic frame with an isoflurane nose cone (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Miniosmotic perfusion pumps (Alzet model 1007; Durect, Cupertino, CA) were implanted subcutaneously on the dorsal aspect of each mouse. Pump cannulae were placed into the lateral ventricle for delivery of drug or vehicle. Pumps delivered 10 mmol/L phosphoramidon (0.11 μL/hr) in saline containing 1 mmol/L ascorbic acid. Mice were sacrificed for analysis 2 weeks after implantation and Aβ was extracted and quantified as described above.

Real-Time PCR Assay of NEP2 Expression

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen), treated with DNase (RNase free; Ambion, Austin, TX), and then reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a mix of oligo-dT and random primers (high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). qRT-PCR was performed with SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed using the comparative ΔΔCt method (normalized to the amplification cycle counts of a house-keeping gene, cyclophilin A). Primer pairs for NEP2 were, 5′-CCCAGGAAAAGGCCATGAAT-3′ and 5′-CCAGGTGTTTATTGTTATCTTCCAAA-3′. Primers pairs for cyclophilin A were, 5′-GGCCGATGACGAGCCC-3′, and 5′-TGTCTTTGGAACTTTGTCTGCAAAT-3′.

Results

Increased Aβ Levels in NEP2 KO Mice

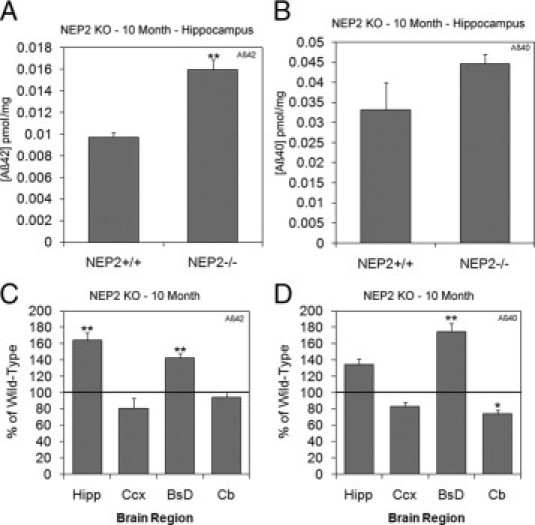

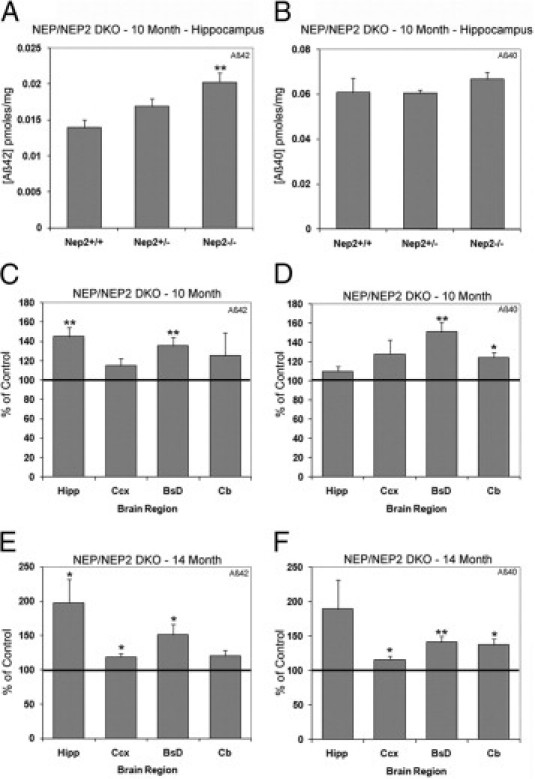

To determine whether NEP2 is required for cerebral control of Aβ, we analyzed Aβ levels in NEP2 KO mice.16 Total Aβ extracts from different brain regions (hippocampus, cerebral cortex, brainstem/diencephalon, and cerebellum) were assayed for Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels by highly sensitive and specific ELISA.4 At 10 months of age, mice deficient in NEP2 demonstrated significantly increased Aβ levels, compared with control NEP2+/+ littermates (Figure 1). In the hippocampus, only Aβ42 levels were significantly elevated (measures of Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels in the hippocampus are presented in Figure 1, A and B, respectively). In addition to the hippocampus, Aβ levels in the brainstem, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum were analyzed, with the data presented as the percentage of the average levels found in control (NEP2+/+) mice (Figure 1, C and D). In the brainstem/diencephalon, both Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels were elevated (Figure 1, C and D).

Figure 1.

Amyloid β (Aβ) levels are increased in NEP2 knockout (KO) mice. Total Aβ42 (A) and Aβ40 (B) levels in the hippocampus of 10-month-old NEP2 wild-type (+/+) (n = 9) and NEP2 KO (−/−) (n = 7) mice. Relative levels of Aβ42 (C) and Aβ40 (D) are reported as a percentage of wild-type mice from hippocampus (Hipp), cerebral cortex (Ccx), brainstem/diencephalon (BsD), and cerebellum (Cb). Values are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Increased Aβ Levels in APPtg/NEP2 KO Mice

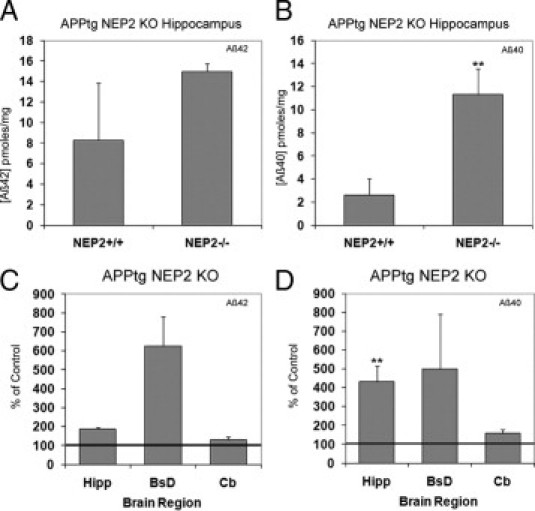

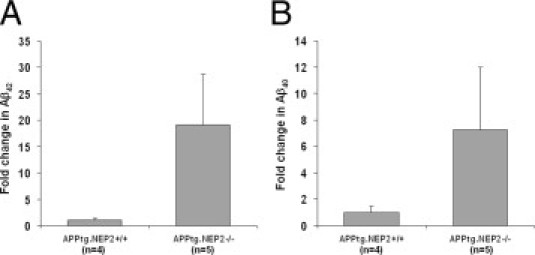

To determine the importance of NEP2-aided Aβ degradation when exposed to high Aβ load, NEP2−/− mice were crossbred with an APP transgenic (APPtg) mouse line (TASD41)20 to generate APPtg/NEP2−/− mice. The APP transgenic line produced approximately an 80-fold increase in Aβ40 levels, as can be observed by comparing the levels of Aβ in the hippocampus from normal APPtg/NEP2+/+ mice (Figure 2B) to wild-type NEP2+/+ mice (Figure 1B). Aβ40 levels in the hippocampus demonstrated more than a fourfold increase in the absence of NEP2, compared with control mice (Figure 2B). It should also be noted that, although the difference was not statistically significant, levels of Aβ42 and Aβ40 in the cerebral cortex were measured at an average 19 ± 9 and 7 ± 5 times the control mice, respectively (Supplemental Figure S2, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 2.

Aβ40 levels are increased in the absence of NEP2 in APPtg mice. Total Aβ42 (A) and Aβ40 (B) levels in 10-month-old APPtg mice in the presence (+/+) (n = 4) and absence (−/−) (n = 5) of the NEP2 gene. Relative levels of Aβ42 (C) and Aβ40 (D) are reported as a percentage of APPtg/NEP2+/+ control mice from the hippocampus (Hipp), brainstem/diencephalon (BsD), and cerebellum (Cb). Values are averages ± SEM. **P < 0.01.

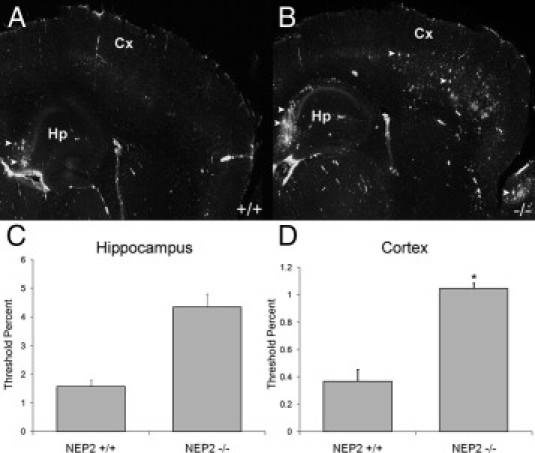

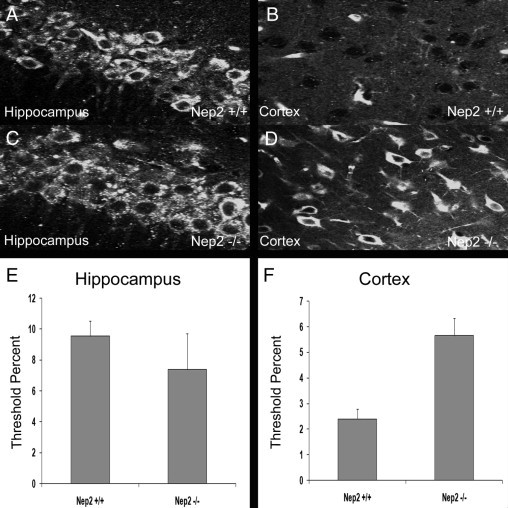

To visualize the pathological effect of a NEP2 knockout in APPtg mice, immunohistochemistry was performed to detect deposited Aβ. The data indicate Aβ plaque deposition elevated in the cortex of APPtg/NEP2−/− mice, compared with controls (Figure 3). Plaques were also observed in the hippocampus. Quantification of the percent area staining positive for Aβ showed increased plaque deposition in the cerebral cortex (Figure 3D). Immunohistochemical analysis of the accumulation of intracellular Aβ showed no significant differences between NEP2+/+ and NEP2−/− groups in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (see Supplemental Figure S3, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). However, the antibody used (4G8) recognizes cell-associated APP and other fragments, which may obscure the detection of elevated intracellular Aβ. Altogether, these data complement the findings of the NEP2 KO experiments (Figure 1) and strengthen the conclusion that NEP2 plays a fundamental role in Aβ degradation. Finally, real-time PCR gene expression analysis revealed no significant increase in the expression levels of the NEP2 gene associated with the presence of the APP gene (see Supplemental Figure S4, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Figure 3.

Aβ plaque deposition is increased in the absence of NEP2 in APPtg mice. Representative fluorescent images of immunohistochemistry staining of deposited Aβ (green) from sagittal brain sections from APPtg/NEP2+/+ mice (A) and APPtg/NEP2−/− mice (40×) (B). Arrowheads indicate examples of plaques. Cx, cerebral cortex; Hp, hippocampus. Quantitation of the % area staining positive for plaque deposition in the hippocampus (C) and cerebral cortex (D) from APPtg/NEP2+/+ mice (n = 4) and APPtg/NEP2−/− mice (n = 5). Values are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05.

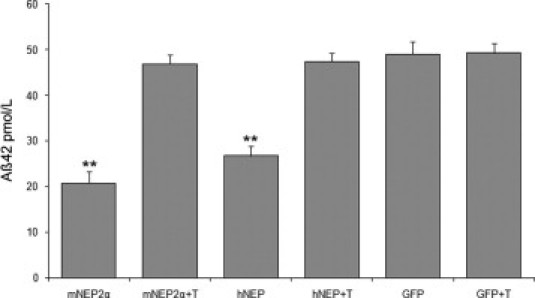

Decreased Aβ42 Levels in Supernatants of mNEP2α Transfected Cells

The data presented above indicate that NEP2 controls both Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels in the brain. However, previous studies in mice have reported that murine NEP2α (the only splice form active against Aβ) degraded Aβ40 with much higher efficiency than Aβ42.9 Therefore, we set out to determine the Aβ42-degrading activity of murine NEP2α in our cell culture assay.10 HEK293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids for murine NEP2α, human NEP, or GFP, and then overlaid with Aβ-conditioned medium (containing 50 pmol/L Aβ42). Aβ42 levels of transfected cell supernatants, with and without thiorphan (100 μmol/L) pretreatment, were measured by specific ELISA (Figure 4). Both mNEP2α and hNEP transfected cell supernatants showed decreased levels of Aβ42 compared with the GFP control (P < 0.01). Addition of the NEP-like inhibitor thiorphan abolished the ability of mNEP2α and hNEP to degrade Aβ, confirming the identity of the endopeptidase activity. These in vitro data demonstrate the ability of NEP2α to degrade Aβ42, corresponding with our data from the mouse studies.

Figure 4.

Murine NEP2α degrades Aβ42. Quantitative analysis of remaining Aβ42 in conditioned cell culture medium containing 50 pmol/L Aβ42 after incubation (5 hours) with HEK293T cells transfected with endopeptidase expressing plasmids (mNEP2α, hNEP) or control plasmid (green fluorescent protein, GFP) in the presence (+T) or absence of thiorphan (100 μmol/L) (n = 4). Values are averages ± SEM. **P < 0.01 compared with GFP.

Increased Aβ Levels in NEP/NEP2 DKO Mice

With the effects of NEP2 KO on Aβ levels identified, we next sought to determine the consequence of deficiencies in both NEP and NEP2 on Aβ levels. NEP KO mice19 were crossed with NEP2 KO mice16 to generate NEP/NEP2 DKO mice. Both 10-month-old and 14-month-old NEP−/−/NEP2−/− DKO mice demonstrated increased Aβ levels, compared with NEP−/−/NEP2+/+ mice (Figure 5). An inverse relationship of the NEP2 gene to Aβ42 level was found in the hippocampi of 10-month-old NEP-lacking mice (Figure 5A). As the gene contributions of NEP2 decreased (NEP2+/+ to NEP2+/− to NEP2−/−), hippocampal Aβ42 levels increased. However, no similar effect was found when measuring Aβ40 in the hippocampus at 10 months (Figure 5B). NEP/NEP2 DKO mice at 10 months of age showed increased Aβ42 in the hippocampus and brainstem/diencephalon, relative to control (NEP−/−/NEP2+/+) mice. Levels of Aβ40 were increased in the brainstem/diencephalon and cerebellum (Figure 5, C and D). At 14 months, the elevated levels of Aβ42 in the hippocampus increased approximately twofold, and both Aβ isoforms were elevated in most brain regions (Figure 5, E and F). Despite elevated levels of Aβ, immunohistochemistry of brains from 14-month-old DKO mice showed no evidence of plaque deposition (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Aβ levels are increased in the absence of NEP2 in NEP KO mice. Total Aβ42 (A) and Aβ40 (B) in the hippocampus of 10-month-old NEP KO mice homozygous (n = 8), heterozygous (n = 5), and deficient (n = 10) for the NEP2 gene. Relative levels of Aβ42 (C, E) and Aβ40 (D, F) from 10-month-old (C, D) and 14-month-old (E, F) NEP/NEP2 DKO mice reported as a percentage of control (NEP−/−/NEP2+/+) mice from hippocampus (Hipp), cerebral cortex (Ccx), brainstem/diencephalon (BsD), and cerebellum (Cb). For the 14-month group, n = 9 for NEP2+/+ and n = 7 for NEP2−/−. Values are averages ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

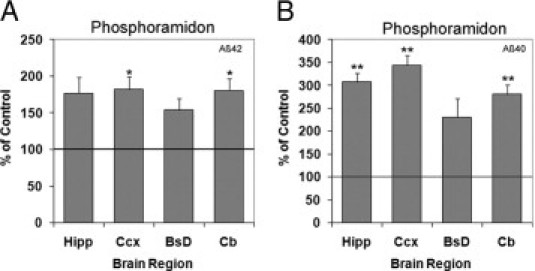

Increased Aβ Levels In Phosphoramidon-Treated NEP/NEP2 DKO Mice

To determine whether NEP/NEP2 DKO mice are still sensitive to NEP-like endopeptidase inhibitors, phosphoramidon was infused intracerebroventricularly using miniosmotic pumps. Phosphoramidon-infused mice showed elevated levels of Aβ42 or Aβ40 in most brain regions compared with controls treated with i.c.v. saline (Figure 6, A and B). Aβ42 levels were significantly elevated in the cortex and cerebellum; Aβ40 levels showed significant increases in all brain regions except the brainstem/diencephalon. These data indicate that phosphoramidon-sensitive endopeptidase activity against Aβ remains in the absence of NEP2 and NEP.

Figure 6.

Increased Aβ levels after phosphoramidon administration in NEP/NEP2 DKO mice. Relative levels of Aβ42 (A) and Aβ40 (B) in DKO mice (10 months old, n = 3) infused with phosphoramidon (i.c.v., 10 mmol/L, 0.11 μL/hr). Data are presented as the percentage of control (saline) Aβ levels from the hippocampus (Hipp), cerebral cortex (Ccx), brainstem/diencephalon (BsD), and cerebellum (Cb). Values are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Through the use of knockout and transgenic technology, the present findings demonstrate the importance of the endopeptidase NEP2 in the Aβ clearance pathway. The results from three mouse lines (NEP2 KO, NEP/NEP2 DKO, and APPtg/NEP2 KO) demonstrated elevations in both Aβ42 and Aβ40 in various brain regions analyzed at multiple time points. For NEP2 KO mice, the regions of highest Aβ elevations were the hippocampus and brainstem/diencephalon. The magnitude of Aβ elevation (1.5-fold) in the hippocampus is similar to that reported for NEP KO mice.4 Although Aβ42 in the hippocampus and both Aβ42 and Aβ40 in the brainstem/diencephalon showed elevations, there was a modest reduction in Aβ40 levels in the cerebellum, compared with wild-type mice (Figure 1D). One possible explanation for this observation is enzymatic up-regulation of alternative Aβ-degrading endopeptidases in response to NEP2 deficiency in these regions. Up-regulation of these alternative enzymes may be sufficient to compensate for the increases in Aβ due to NEP2 deficiency.

Although the NEP2 KO data clearly showed a significant role for NEP2 in endogenous Aβ regulation, the effect of NEP2 on Aβ degradation when challenged with a high level of Aβ remained to be determined. This issue was addressed with the use of APPtg mice, which dramatically overproduce Aβ.20 In combination with the APP transgene, NEP2 deficiency produced more dramatic elevation in Aβ40 levels, strongly supporting a role for NEP2 in Aβ regulation (Figure 2). Although no elevations in Aβ were seen in the cerebral cortex of NEP2 KO mice (Figure 1), a dramatic increase in plaque deposition was observed in the cerebral cortex of APP transgenic/NEP2 KO mice (Figure 3). This could be explained if the compensating mechanism that occurs in the cortex of single-knockout mice were somewhat limited in capacity. Thus, when challenged by very high levels of Aβ, this compensation is overcome, resulting in considerable accumulation in Aβ. Also, it should be noted that APP/Aβ expression levels in APP transgenics are also dependent on the transgene promoter and genomic integration site. The APP transgenic line we have used is reported to express APP/Aβ more strongly in the cerebral cortex.20

The accumulation of intracellular Aβ has been implicated as a major mediator of Aβ toxicity.25 Our analysis of intracellular Aβ did not show significant increases in intracellular accumulation (see Supplemental Figure S3, at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). The lack of a clear effect of NEP2 deficiency on intracellular Aβ, compared with plaque deposition, may be due to saturation of the intracellular Aβ accumulation process. This hypothesis suggests that, even in the presence of the NEP2 gene, Aβ levels are dramatically elevated in this transgenic model, resulting in high levels of intracellular Aβ that are difficult to elevate further. Also, the contribution of cellular APP and its other fragments complicates this analysis. Finally, one limitation of the present study is that our analysis quantified total Aβ and did not specifically measure aggregated forms of Aβ, including toxic soluble oligomers.26 This analysis has important implications for the ultimate relevance of NEP2 to AD, and we plan to address it in future studies.

Analyzing Aβ levels in NEP2 KO mice also deficient for NEP provides further insight into the role of these key endopeptidases in Aβ catabolism. The results from NEP/NEP2 DKO mice indicate that ablation of the NEP2 gene leads to further elevated Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels in the brain, compared with single knockout of NEP (Figure 5). Our analysis also confirms that ablation of NEP alone produces elevated Aβ levels. For example, NEP KO mice (NEP−/−.NEP2+/+) displayed approximately 1.5 to 2 times the Aβ levels of wild-type mice (compare Figure 1, A and B, with Figure 5, A and B). In addition, the absence of NEP and NEP2 produces an additive elevation in Aβ, verifying that both endopeptidases cooperate to control Aβ levels in the brain. Our analysis did not reveal a significant increase in Aβ levels between 10-month-old and 14-month-old mice (data not shown). Previous studies have demonstrated that treating rodents with inhibitors of NEP/NEP2 (ie, phosphoramidon and thiorphan) produces more dramatic elevations in Aβ (30- to 50-fold).2,5,6 However, despite the lack of both NEP and NEP2 genes, only modest elevations in Aβ peptides were observed in our double-knockout studies—well below known plaque-inducing levels. As expected, the immunohistochemical analysis of 14-month-old DKO mice did not show evidence of plaque deposition (data not shown). Therefore, other Aβ clearing mechanisms must be compensating for the loss of both NEP and NEP2.

Supporting this theory, DKO mice treated with phosphoramidon produced increases in both Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels in certain brain regions (Figure 6). It should be noted that, considering the smaller pump size and shorter duration of this study, the values of Aβ elevation due to phosphoramidon infusion were comparable to the values seen with lower doses previously used by Nisemblat and colleagues.6 These elevations in Aβ resulting from the application of an NEP/NEP2 inhibitor suggest the existence of yet other NEP-like endopeptidases that are involved in Aβ catabolism. Given that both NEP and NEP2 are M13 proteases, the exploration of other enzymes in this family that are sensitive to phosphoramidon may lead to the discovery of additional enzymes involved in Aβ metabolism. Possible enzymes cooperating with NEP and NEP2 include endothelin-converting enzymes (ECE), phosphate-regulating gene with homologies to endopeptidases on the X chromosome (PHEX), and damage-induced neuronal endopeptidase (DINE). The ECE are clear candidates because they are sensitive to phosphoramidon. However, early studies using thiorphan infusion in rodents suggest that ECEs are not involved in the drug's effect on Aβ.2,5 PHEX and DINE share 39% and 36% identity to NEP, respectively.8 It should be mentioned that aminopeptidases or other Aβ-degrading enzymes may also be affected by the infusion of relatively large concentrations of NEP-like inhibitors in these experiments. It is worth noting that phosphoramidon produced stronger effects on Aβ40 in the absence of both NEP and NEP2, suggesting that the remaining NEP-like activity may more efficiently degrade Aβ40 compared with Aβ42. It is possible, therefore, that NEP and NEP2 could be the major catabolic NEP-like enzymes (ie, phosphoramidon-sensitive enzymes) responsible for clearing Aβ42.

Our analyses clearly demonstrate that murine NEP2 degrades both isoforms of Aβ. However, a previous study reported that murine NEP2 degrades Aβ40 much more efficiently than does Aβ42.9 To address this issue, we constructed a murine NEP2α expression vector. Our results, using Aβ-conditioned medium overlaid on cells transfected with our engineered murine NEP2α construct, demonstrate the ability of mNEP2α to degrade Aβ42 in the extracellular compartment (Figure 4). A possible explanation for the observed differences between our findings and the previous study may be the different experimental designs used. The previous study measured the cleavage of Aβ from enzymes extracted in membrane-bound fractions,9 as opposed to the present study's measurements using the enzyme expressed from cells in culture.

Besides identifying a novel NEP-like enzyme that controls Aβ in vivo, our results have implications for potential therapeutic applications. Experiments using NEP gene therapy have been conducted in APPtg mice using a variety of systems to overexpress NEP [reviewed by Marr and Spencer3]. The results of these therapeutic studies showed reduced plaque pathology and memory improvements in treated animals.21,27–35 However, because current approaches could ultimately be ineffective or produce unwanted side effects,36–38 more tools are always welcome in the search for therapies for AD, and exploration of the potential of NEP2 as a therapeutic agent is warranted.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated in three different mouse models that NEP2 is required for the endogenous regulation of Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels in the rodent brain. However, unlike the results of thiorphan and phosphoramidon infusion studies, only modest elevations in these peptides were observed in nontransgenic mice lacking NEP and NEP2, suggesting the existence of redundant proteolytic systems for controlling Aβ levels. These systems may include the class of phosphoramidon-sensitive (NEP-like) enzymes.

Acknowledgment

We thank Andrew Mensing for assistance with this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Figure S1.

Examples of genotyping assays for the NEP2/NEP knockout and APPtg mice. UV images of ethidium bromide-stained agarose electrophoresis gels showing DNA PCR products using specific primers (see Methods section) to amplify genomic template DNA extracted from mouse ear clippings.

Figure S2.

Aβ levels in the cerebral cortex of APPtg mice in the presence and absence of the NEP2 gene. Relative levels of Aβ42 (A) and Aβ40 (B) measured by specific ELISA. Data are presented as the fold change compared with the average value from APPtg/NEP2+/+ control mice. Values are means ± SEM.

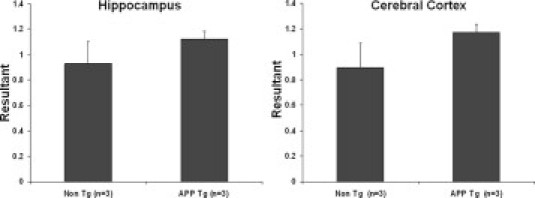

Figure S3.

Analysis of intracellular Aβ accumulation in the presence and absence of the NEP2 gene. Representative fluorescent images of immunohistochemistry staining of Aβ from sagittal brain sections from APPtg/NEP2+/+ (A, B) and APPtg/NEP2−/− (C, D) mice from the hippocampus (A, C) and cerebral cortex (B, D). Quantitation of the % area staining positive for Aβ in the hippocampus (E) and cerebral cortex (F) from APPtg/NEP2+/+ (n = 4) and APPtg/NEP2−/− (n = 5) mice. Values are averages ± SEM.

Figure S4.

Real-time PCR analysis of NEP2 expression on APP transgenic and non-transgenic mice. Coding DNA samples from mouse brain tissues (2 months old) were analyzed for NEP2 gene expression using the ΔΔCt-method (compared with cyclophilin expression) of quantitative real-time PCR. Data are presented as the mean of arbitrary expression units (resultant) ± SEM.

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R., Johnson E., Ziegler-Graham K., Arrighi H.M. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwata N., Tsubuki S., Takaki Y., Watanabe K., Sekiguchi M., Hosoki E., Kawashima-Morishima M., Lee H.J., Hama E., Sekine-Aizawa Y., Saido T.C. Identification of the major Abeta1-42-degrading catabolic pathway in brain parenchyma: suppression leads to biochemical and pathological deposition. Nat Med. 2000;6:143–150. doi: 10.1038/72237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marr R.A., Spencer B.J. NEP-like Endopeptidases and Alzheimer's Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:223–229. doi: 10.2174/156720510791050849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwata N., Tsubuki S., Takaki Y., Shirotani K., Lu B., Gerard N.P., Gerard C., Hama E., Lee H.J., Saido T.C. Metabolic regulation of brain Abeta by neprilysin. Science. 2001;292:1550–1552. doi: 10.1126/science.1059946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolev I., Michaelson D.M. A nontransgenic mouse model shows inducible amyloid-beta (Abeta) peptide deposition and elucidates the role of apolipoprotein E in the amyloid cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13909–13914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404458101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nisemblat Y., Belinson H., Dolev I., Michaelson D.M. Activation of the amyloid cascade by intracerebroventricular injection of the protease inhibitor phosphoramidon. Neurodegener Dis. 2008;5:166–169. doi: 10.1159/000113692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda K., Emoto N., Raharjo S.B., Nurhantari Y., Saiki K., Yokoyama M., Matsuo M. Molecular identification and characterization of novel membrane-bound metalloprotease, the soluble secreted form of which hydrolyzes a variety of vasoactive peptides. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32469–32477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghaddar G., Ruchon A.F., Carpentier M., Marcinkiewicz M., Seidah N.G., Crine P., DesGroseillers L., Boileau G. Molecular cloning and biochemical characterization of a new mouse testis soluble-zinc-metallopeptidase of the neprilysin family. Biochem J. 2000;347:419–429. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3470419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirotani K., Tsubuki S., Iwata N., Takaki Y., Harigaya W., Maruyama K., Kiryu-Seo S., Kiyama H., Iwata H., Tomita T., Iwatsubo T., Saido T.C. Neprilysin degrades both amyloid beta peptides 1-40 and 1-42 most rapidly and efficiently among thiorphan- and phosphoramidon-sensitive endopeptidases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21895–21901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang J.Y., Bruno A.M., Patel C.A., Huynh A.M., Philibert K.D., Glucksman M.J., Marr R.A. Human membrane metallo-endopeptidase-like protein degrades both beta-amyloid 42 and beta-amyloid 40. Neuroscience. 2008;155:258–262. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raharjo S.B., Emoto N., Ikeda K., Sato R., Yokoyama M., Matsuo M. Alternative splicing regulates the endoplasmic reticulum localization or secretion of soluble secreted endopeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25612–25620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oh-Hashi K., Ohkubo K., Shizu K., Fukuda H., Hirata Y., Kiuchi K. Biosynthesis, processing, trafficking, and enzymatic activity of mouse neprilysin 2. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;313:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9747-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Facchinetti P., Rose C., Schwartz J.C., Ouimet T. Ontogeny, regional and cellular distribution of the novel metalloprotease neprilysin 2 in the rat: a comparison with neprilysin and endothelin-converting enzyme-1. Neuroscience. 2003;118:627–639. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)01002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouimet T., Facchinetti P., Rose C., Bonhomme M.C., Gros C., Schwartz J.C. Neprilysin II: a putative novel metalloprotease and its isoforms in CNS and testis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;271:565–570. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpentier M., Marcinkiewicz M., Boileau G., DesGroseillers L. The neuropeptide-degrading enzyme NL1 is expressed in specific neurons of mouse brain. Peptides. 2003;24:1083–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(03)00177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpentier M., Guillemette C., Bailey J.L., Boileau G., Jeannotte L., DesGroseillers L., Charron J. Reduced fertility in male mice deficient in the zinc metallopeptidase NL1. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4428–4437. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4428-4437.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rose C., Voisin S., Gros C., Schwartz J.C., Ouimet T. Cell-specific activity of neprilysin 2 isoforms and enzymic specificity compared with neprilysin. Biochem J. 2002;363:697–705. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner A.J., Nalivaeva N.N. New insights into the roles of metalloproteinases in neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;82:113–135. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)82006-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu B., Gerard N.P., Kolakowski L.F., Jr, Bozza M., Zurakowski D., Finco O., Carroll M.C., Gerard C. Neutral endopeptidase modulation of septic shock. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2271–2275. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rockenstein E., Mallory M., Mante M., Sisk A., Masliaha E. Early formation of mature amyloid-beta protein deposits in a mutant APP transgenic model depends on levels of Abeta(1-42) J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:573–582. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer B., Marr R.A., Rockenstein E., Crews L., Adame A., Potkar R., Patrick C., Gage F.H., Verma I.M., Masliah E. Long-term neprilysin gene transfer is associated with reduced levels of intracellular Abeta and behavioral improvement in APP transgenic mice. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marr R.A., Addison C.L., Snider D., Muller W.J., Gauldie J., Graham F.L. Tumour immunotherapy using an adenoviral vector expressing a membrane-bound mutant of murine TNF alpha. Gene Ther. 1997;4:1181–1188. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singer O., Marr R.A., Rockenstein E., Crews L., Coufal N.G., Gage F.H., Verma I.M., Masliah E. Targeting BACE1 with siRNAs ameliorates Alzheimer disease neuropathology in a transgenic model. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1343–1349. doi: 10.1038/nn1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham F.L., van der Eb A.J. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973;52:456–467. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oddo S., Caccamo A., Shepherd J.D., Murphy M.P., Golde T.E., Kayed R., Metherate R., Mattson M.P., Akbari Y., LaFerla F.M. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashe K.H., Zahs K.R. Probing the biology of Alzheimer's disease in mice. Neuron. 2010;66:631–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Amouri S.S., Zhu H., Yu J., Marr R., Verma I.M., Kindy M.S. Neprilysin: an enzyme candidate to slow the progression of Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1342–1354. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang S.M., Mouri A., Kokubo H., Nakajima R., Suemoto T., Higuchi M., Staufenbiel M., Noda Y., Yamaguchi H., Nabeshima T., Saido T.C., Iwata N. Neprilysin-sensitive synapse-associated amyloid-beta peptide oligomers impair neuronal plasticity and cognitive function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17941–17951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601372200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leissring M.A., Farris W., Chang A.Y., Walsh D.M., Wu X., Sun X., Frosch M.P., Selkoe D.J. Enhanced proteolysis of beta-amyloid in APP transgenic mice prevents plaque formation, secondary pathology, and premature death. Neuron. 2003;40:1087–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00787-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marr R.A., Rockenstein E., Mukherjee A., Kindy M.S., Hersh L.B., Gage F.H., Verma I.M., Masliah E. Neprilysin gene transfer reduces human amyloid pathology in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1992–1996. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-01992.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poirier R., Wolfer D.P., Welzl H., Tracy J., Galsworthy M.J., Nitsch R.M., Mohajeri M.H. Neuronal neprilysin overexpression is associated with attenuation of Abeta-related spatial memory deficit. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohajeri M.H., Wolfer D.P. Neprilysin deficiency-dependent impairment of cognitive functions in a mouse model of amyloidosis. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:717–726. doi: 10.1007/s11064-009-9919-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madani R., Poirier R., Wolfer D.P., Welzl H., Groscurth P., Lipp H.P., Lu B., El Mouedden M., Mercken M., Nitsch R.M., Mohajeri M.H. Lack of neprilysin suffices to generate murine amyloid-like deposits in the brain and behavioral deficit in vivo. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:1871–1878. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y., Studzinski C., Beckett T., Guan H., Hersh M.A., Murphy M.P., Klein R., Hersh L.B. Expression of neprilysin in skeletal muscle reduces amyloid burden in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1381–1386. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guan H., Liu Y., Daily A., Police S., Kim M.H., Oddo S., LaFerla F.M., Pauly J.R., Murphy M.P., Hersh L.B. Peripherally expressed neprilysin reduces brain amyloid burden: a novel approach for treating Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:1462–1473. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iijima-Ando K., Hearn S.A., Granger L., Shenton C., Gatt A., Chiang H.C., Hakker I., Zhong Y., Iijima K. Overexpression of neprilysin reduces Alzheimer amyloid-beta42 (Abeta42)-induced neuron loss and intraneuronal Abeta42 deposits but causes a reduction in cAMP-responsive element-binding protein-mediated transcription, age-dependent axon pathology, and premature death in Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:19066–19076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710509200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meilandt W.J., Cisse M., Ho K., Wu T., Esposito L.A., Scearce-Levie K., Cheng I.H., Yu G.Q., Mucke L. Neprilysin overexpression inhibits plaque formation but fails to reduce pathogenic Abeta oligomers and associated cognitive deficits in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1977–1986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2984-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walther T., Albrecht D., Becker M., Schubert M., Kouznetsova E., Wiesner B., Maul B., Schliebs R., Grecksch G., Furkert J., Sterner-Kock A., Schultheiss H.P., Becker A., Siems W.E. Improved learning and memory in aged mice deficient in amyloid beta-degrading neutral endopeptidase. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]