Artemisinin: Discovery from the Chinese Herbal Garden (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2012 Sep 16.

Abstract

This year’s Lasker DeBakey Clinical Research Award goes to Youyou Tu for the discovery of artemisinin and its use in the treatment of malaria—a medical advance that has saved millions of lives across the globe, especially in the developing world.

The future benefits of many seminal discoveries in basic biomedical sciences are not always obvious in the short run. But for a handful of others, the impact on human health is immediately clear. Such is the case for the discovery by Youyou Tu and colleagues of artemisinin (also known as Qinghaosu) for treatment of malaria. Artemisinin has been the frontline treatment since the late 1990s and has saved countless lives, especially among the world’s poorest children.

The Promise of Project 523

The story of artemisinin began in the unlikely atmosphere of the Cultural Revolution in China as a government initiative to aid the North Vietnamese in their war with the United States. During the war, malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum was a major problem that spurred research efforts on both sides of the battlefield. In the US, these efforts culminated in the discovery of mefloquine, a compound that was curative in a single dose against chloroquine-resistant parasites (Trenholme et al.,1975). TheNorthVietnamese, however, lacked a research infrastructure and thus turned to China for help.

Under the instructions of Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou, a meeting was held on May 23, 1967 in Beijing to discuss the problem of drug-resistant malaria parasites. This led to a secret nationwide program called project 523, involving over 500 scientists in ~60 different laboratories and institutes (Zhang et al., 2006). Although the project’s short-term goal was to produce antimalarial drugs that could immediately be used in the battlefield (by 1969 three treatments were established), the project’s long-term goal was to search for new antimalarial drugs by screening synthetic chemicals and by searching recipes and practices of traditional Chinese medicine.

Because this work was considered a military secret, no communication about the research to the outside world was allowed, and in any case, during the tumult of the Cultural Revolution, publication in scientific journals was forbidden. For these reasons, no one outside of project 523 knew about the work. Yet within the project, information flowed freely between the members of the various research groups, and findings were presented at their frequent joint meetings.

Without a publication record, who should be credited with the discovery of artemisinin? The answer to this question was not generally known when we (X.S. and L.H.M.) began, in 2007, to delve into the history of the discovery. Our findings left no doubt that the major credit must go to Youyou Tu, who was a principle investigator at the Institute of Chinese Meteria Medica, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CACAMS). In January 1969, Professor Tu led a team in screening the literature and recipes of traditional Chinese medicine under project 523. She was chosen to present the work of project 523 for the first time in October 1981 in Beijing to a World Health Organization (WHO) visiting study group on chemotherapy of malaria (Tu, 1981).

From Ancient Recipe to Modern Drug

During their search, Youyou Tu and colleagues investigated more than 2,000 recipes of Chinese traditional herbs, compiling 640 recipes that might have some antimalarial activity. They tested in a rodent malaria model more than 200 recipes with Chinese traditional herbs and 380 extracts from the herbs. Among the promising results, extracts from Artemisia annua L. (Qinghao), a type of wormwood native to Asia, were shown to inhibit parasite growth by 68%. Follow-up studies, however, only achieved 12% to 40% inhibition. Professor Tu reasoned that the low inhibition could be due to a low concentration of the active ingredient in the preparation and began to improve the methods of extraction. After reading the ancient Chinese medical description, “take one bunch of Qinghao, soak in two sheng (~0.4 liters) of water, wring it out to obtain the juice and ingest it in its entirety” in The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergency Treatments by Ge Hong (283–343 CE) during the Jin Dynasty, she realized that traditional methods of boiling and high-temperature extraction could damage the active ingredient. Indeed, a much better extract was obtained after switching from ethanol to ether extraction at lower temperature.

However, the extract was still toxic. Professor Tu then further removed from the extract an acidic portion that contained no antimalarial activity, leaving a neutral extract with reduced toxicity and improved antimalarial activity. The neutral extract, termed extract number 191, was tested in the mouse malaria, Plasmodium berghei, and achieved 100% inhibition in October 1971. She presented her findings at a 523 meeting held in Nanjing on March 8, 1972, providing some critical parameters for other teams to quickly obtain pure artemisinin crystals. Although Tu’s team struggled to obtain high-quality crystals from the plant in the following months, two teams (Zeyuan Luo, Yunnan Institute of Drug Research and the late Zhangxing Wei, Shandong Institute of Chinese Traditional Medicine), using the information and methods she used, soon obtained pure crystals from A. annua L. that were highly active against rodent malaria parasites. Tests in humans by Guoqiao Li, Guangzhou University of Chinese Traditional Medicine, using the artemisinin crystals from Yunnan Institute of Drug Research showed good activity against malaria infection.

Interestingly, the paper describing artemisinin’s X-ray crystal structure, pharmacology, and efficacy against non-severe and severe cerebral malaria listed no specific authors, who were identified instead as the Qinghaosu Antimalarial Coordinating Research Group (1979). The paper showed that artemisinin is a sesquipene lactone with an endoperoxide, and that the endoperoxide is required for its antimalarial activity (Figure 1). In 1985, Klayman, working in the US at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), described the isolation of the same compound and its structure from Artemisia annua (sweet wormwood), which grew along the shores of the Potomac River. Klayman pointed out that there are few naturally occurring endoperoxides described in plants. Although numerous hydroxoperoxides had been tested at WRAIR, none were found to have antimalarial activity (Klayman, 1985).

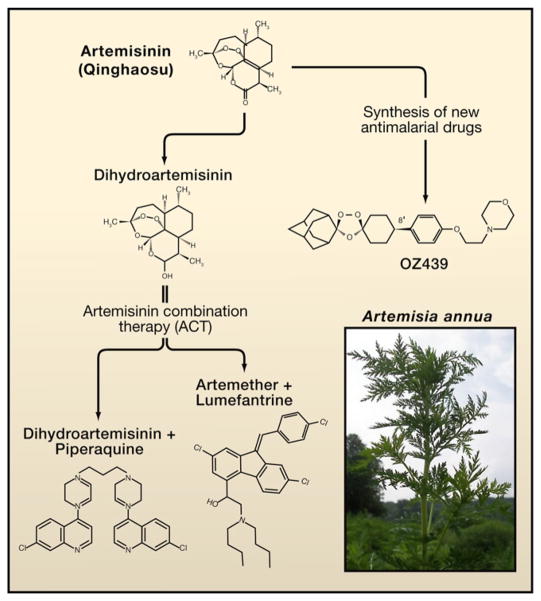

Figure 1. The Antimalarial Drug Artemisinin (Qinghaosu).

Since the discovery of artemisinin from Artemisia annua L., a plant used in traditional Chinese medicine, by Youyou Tu and colleagues, many derivatives have been synthesized, including dihydroartemisinin, which is more active than artemisinin. To protect this important antimalarial drug, combination therapy with another antimalarial drug is the only treatment used today. The future synthesis of new antimalarial drugs may be possible, originating from the endoperoxide bridge that is required for artemisinin’s antimalarial activity (Charman et al., 2011).

Two clinical studies headed by Professor Gouqiao Li compared artemisinin and mefloquine. These studies were the first to suggest that combination therapy should be considered to prevent recurrence and development of resistance (Jiang et al., 1982; Li et al., 1984). Artemisinin works quickly within hours compared to mefloquine’s slow parasite clearance, but because of its short half-life, artemisinin requires another drug in combination to obtain a cure. Patients recovered so quickly after taking artemisinin that they would not continue treatment after they felt better and thus were ultimately not cured. Such incomplete treatment may promote drug resistance. Li’s group also developed suppositories containing artemisinin to treat cerebral malaria that are now being used in field clinics in Africa. Shortening the time to treatment by the use of suppositories improves survival.

After learning of this important discovery by the Chinese, Nick White, who was working in Thailand as a professor at Oxford, began the study of artemisinin derivatives. He confirmed its rapid activity and the need for a partner drug to clear the parasitemia and became the primary proponent for the use of artemisinin derivatives in combination therapy, which is now the standard treatment worldwide. In 2010, he was honored by the Canadian Gairdner Award for this important work.

Project 523 developed, in addition to artemisinin, a number of products that are used in combination with artemisinin, including lumefantrine, piperaquine, and pyronaridine. Their success reflects the unique spirit of collaboration from a large number of scientists and institutions involved in the search for antimalarial drugs.

An Ongoing Battle against Resistance

An important unanswerable question is how effective artemisinin or its derivatives will be in the future. We can perhaps gain perspective from the history of other antimalarial drugs. The initial mortality from malaria was extremely high throughout the world before the introduction of the last herbal medicine, quinine. Wherever it was introduced, there was a marked decrease in mortality. When the price of quinine decreased in Italy, leading to the increased use of quinine, the mortality markedly decreased. It is not surprising that when P. falciparum became resistant to the synthetic antimalarial drug chloroquine, mortality in children rose dramatically. Once the basis of resistance to chloroquine was identified as mutations in the gene encoding the putative chloroquine transporter in the food vacuole, PfCRT (Fidock et al., 2000), it became evident that the mutations had not originated in Africa but were introduced from Southeast Asia (Wootton et al., 2002).

A major challenge to public health officials in African countries is to decide when to change their antimalarial drug policy. Such decisions require a careful review of efficacy given that the choices available are limited. However, during these transitions, deaths (particularly of children) occur before the decision to change regimens is made. After chloroquine, the next antimalarial drug to be introduced to Africa was sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (Fansidar), which is a synergistic antimalarial combination. After its introduction, Fansidar resistance, due to mutations in both P. falciparum dihydrofolate reductase and dihydropteroate synthetase, has been widely reported. Likewise, resistance to mefloquine has occurred in Asia, where it was introduced as a stand-alone antimalarial drug. Unfortunately, mefloquine resistance has also undermined the efficacy of its combination treatment with Fansidar, called Fansimef. Additionally, mefloquine is expensive to produce and cannot fit the financial needs of the African population.

The insistence that artemisinin derivatives must be used in combination therapy (Figure 1) may protect it from resistance, at least for some time. This will require careful evaluation of the efficacy of the added drug to protect artemisinin. The one hope is that the use of artemisinin combination therapy will remain effective and that mortality associated with a change in drugs will be prevented.

We also face the question of what drug to adopt next if resistance to artemisinin becomes a problem. Resistance to artemisinin derivatives may be arising on the Thai-Cambodian border (Dondorp et al., 2009), evident in the longer time it takes for treatment to clear parasites from the blood than has been reported previously or from other areas of Thailand. However, a similar concentration of artemisinin as originally used for the sensitive parasites can kill the resistant parasites in vitro and in vivo. Although there are disagreements as to whether this indicates resistance, the prudent approach is to assume that it is early resistance and to try to limit the spread of these parasites. This would mirror earlier epidemiological patterns of malarial drug resistance—for both chloroquine and pyrimethamine-sulfidoxine, resistance originated in Southeast Asia and later spread to Africa. Vigilance is particularly warranted given that resistance to antimalarial drugs can develop rapidly. The one exception has been quinine, in use for hundreds of years, and resistance has only developed slowly with the level of drug required for cure increasing with time. Our hope is that a similar course will be seen for the other herbal medicine, artemisinin.

The Future of Antimalarial Treatments

Efforts are ongoing to make other antimalarial compounds based on the structure of artemisinin and its mechanism of action. It is known that artemisinin requires hemoglobin digestion and the release of iron containing heme, which induces oxidative stress (Klonis et al., 2011). As noted by Klayman (1985), there are few natural products with an endoperoxide, and this peroxide also offers an opportunity to make new antimalarial drugs (Charman et al., 2011).

But who is going to develop these new drugs? Artemisinin’s discovery was spurred on by war, and it can be hoped that more peaceful motivations will drive the development of future malaria treatments. Yet, malaria has not been a major target of drug companies, which have historically focused their efforts on more profitable treatments for diseases prevalent in affluent countries. Filling this gap, joint public-private companies, such as the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV), may prove a successful model funding drug development. In addition, modern approaches, such as high-throughput screening a large number of compounds, may also provide new leads for antimalarial drugs.

Another question that is raised with any treatment or control measure is, how effective is it in reducing mortality? In many areas of the world, two measures of malaria control were introduced simultaneously: artemisinin combination therapy and bednets treated with long-acting pyrethroid insecticides. As a result, many areas in Africa have shown a reduced incidence of malaria, although a careful analysis of the data fails to identify the intervention that led to reduced disease and, as a consequence, reduced death (O’Meara et al., 2010). In recent years, there has been a disturbing increase in pyrethroid resistance by malaria vectors in Africa (Ranson et al., 2011). A study in Dielmo, Senegal, where transmission is continuous at a high level because of a stream that runs through the village from an underwater spring, showed a great reduction of disease after the introduction of control methods, but this reduction was followed by a recent rebound (Trape et al., 2011), perhaps as a result of insecticide resistance. If such resistance becomes widespread, people will be completely dependent on artemisinin combination therapy for preventing disease and death given that many have lost some of their immunity as a result of the marked reduction in malaria. As long as the mosquito species that harbor the parasite remain in Africa, such recurrences can be expected.

Although the challenges of combating malaria remain daunting, the discovery of artemisinin by Youyou Tu and her many colleagues in the Chinese scientific community offers hope and is a great achievement in the history of modern medicine.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Susan Pierce, LIG, NIAID and Thomas E. Wellems, LMVR, NIAID for suggestions on the manuscript and for suggestions on the figure drawn by Alan Hoofring. This work has been supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. We thank Dr. Jian Li of Xiamen University for assistance in translating this article into Chinese (translation can be found online at http://www.cell.com/LaskerAward-Chinese).

References

- Charman SA, Arbe-Barnes S, Bathurst IC, Brun R, Campbell M, Charman WN, Chiu FCK, Chollet J, Craft JC, Creek DJ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4400–4405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015762108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, Lwin KM, Ariey F, Hanpithakpong W, Lee SJ, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidock DA, Nomura T, Talley AK, Cooper RA, Dzekunov SM, Ferdig MT, Ursos LM, Sidhu AB, Naudé B, Deitsch KW, et al. Mol Cell. 2000;6:861–871. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(05)00077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang JB, Li GQ, Guo XB, Kong YC, Arnold K. Lancet. 1982;2:285–288. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klayman DL. Science. 1985;228:1049–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.3887571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonis N, Crespo-Ortiz MP, Bottova I, AbuBakar N, Kenny S, Rosenthal PJ, Tilley L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:11405–11410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104063108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GQ, Arnold K, Guo XB, Jian HX, Fu LC. Lancet. 1984;2:1360–1361. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara WP, Mangeni JN, Steketee R, Greenwood B. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:545–555. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qinghaosu Antimalarial Coordinating Research Group. Chin Med J (Engl) 1979;12:811–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranson H, N’guessan R, Lines J, Moiroux N, Nkuni Z, Corbel V. Trends Parasitol. 2011;27:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trape JF, Tall A, Diagne N, Ndiath O, Ly AB, Faye J, Dieye-Ba F, Roucher C, Bouganali C, Badiane A, et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70194-3. Published online August 17 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenholme CM, Williams RL, Desjardins RE, Frischer H, Carson PE, Rieckmann KH, Canfield CJ. Science. 1975;190:792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.1105787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu YY. Fourth Meeting of the WHO Scientific Working Group on the Chemotherapy of Malaria: TDR/CHEMAL-SWG (4)/(QHS)/81.3; Beijing, China. 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wootton JC, Feng X, Ferdig MT, Cooper RA, Mu J, Baruch DI, Magill AJ, Su XZ. Nature. 2002;418:320–323. doi: 10.1038/nature00813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JF, Zhou KD, Zhou YQ, Fu LS, Wang HS, Song SY. A detailed chronological record of project 523 and the discovery and development of qinghaosu (artemisinin) Guangzhou, China: Yangcheng Evening News Publishing Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]