Evidence for autosomal recessive inheritance in SPG3A caused by homozygosity for a novel ATL1 missense mutation (original) (raw)

Abstract

Hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs) comprise a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by progressive spasticity and weakness of the lower limbs. Autosomal dominant and ‘pure' forms of HSP account for ∼80% of cases in Western societies of whom 10% carry atlastin-1 (ATL1) gene mutations. We report on a large consanguineous family segregating six members with early onset HSP. The pedigree was compatible with both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive inheritance. Whole-exome sequencing and segregation analysis revealed a homozygous novel missense variant c.353G>A, p.(Arg118Gln) in ATL1 in all six affected family members. Seven heterozygous carriers, five females and two males, showed no clinical signs of HSP with the exception of sub-clinically reduced vibration sensation in one adult female. Our combined findings show that homozygosity for the ATL1 missense variant remains the only plausible cause of HSP, whereas heterozygous carriers are asymptomatic. This apparent autosomal recessive inheritance adds to the clinical complexity of spastic paraplegia 3A and calls for caution using directed genetic screening in HSP.

Keywords: SPG3A, autosomal recessive, ATL1 gene

Introduction

Hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs) or spastic paraplegias (SPGs) belong to a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of disorders caused by upper motor neuron degeneration.1 To date, more than 55 different gene loci have been mapped for HSP (SPG1-SPG56) including autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive and the more rare X-linked forms.2 The dominant cases are predominantly ‘pure' forms with symptoms mainly restricted to the lower extremities. Heterozygous mutations in the SPAST gene cause SPG4 and account for 40% of all autosomal dominant cases followed by mutations in the ATL1 gene in SPG3A in ∼10% of cases.2, 3, 4 Autosomal recessive forms of HSP comprise mainly ‘complicated' clinical types with extensive neurological and non-neurological manifestations.5, 6, 7 The majority of HSP genes are associated with very rare or even unique clinical forms. Thus, yet unknown genetic mechanisms are a conceivable explanation for why directed gene analysis fails to identify mutations in ∼20% of cases.8 Another plausible explanation for the ‘missed heritability' in HSP is uncertainty about inheritance patterns as illustrated here in SPG3A, a ‘pure' form of SPG usually apparent before the age of 10 years.9, 10 In SPG3A, diagnosis may be complicated owing to late onset and, in particular, to reduced penetrance9 that may be as low as 30% for specific ATL1 mutations.9, 11, 12, 13, 14 A further complicating factor in SPG3A is a gender-dependent penetrance with a preponderance for males in some families.15

We identified a large family segregating an uncomplicated and early onset form of HSP. Exome sequencing revealed homozygosity for a novel ATL1 missense variant in the six affected family members, whereas heterozygous carriers are asymptomatic. We therefore consider autosomal recessive SPG3A as a novel albeit rare genetic form of unexplained HSP.

Materials and methods

Patients

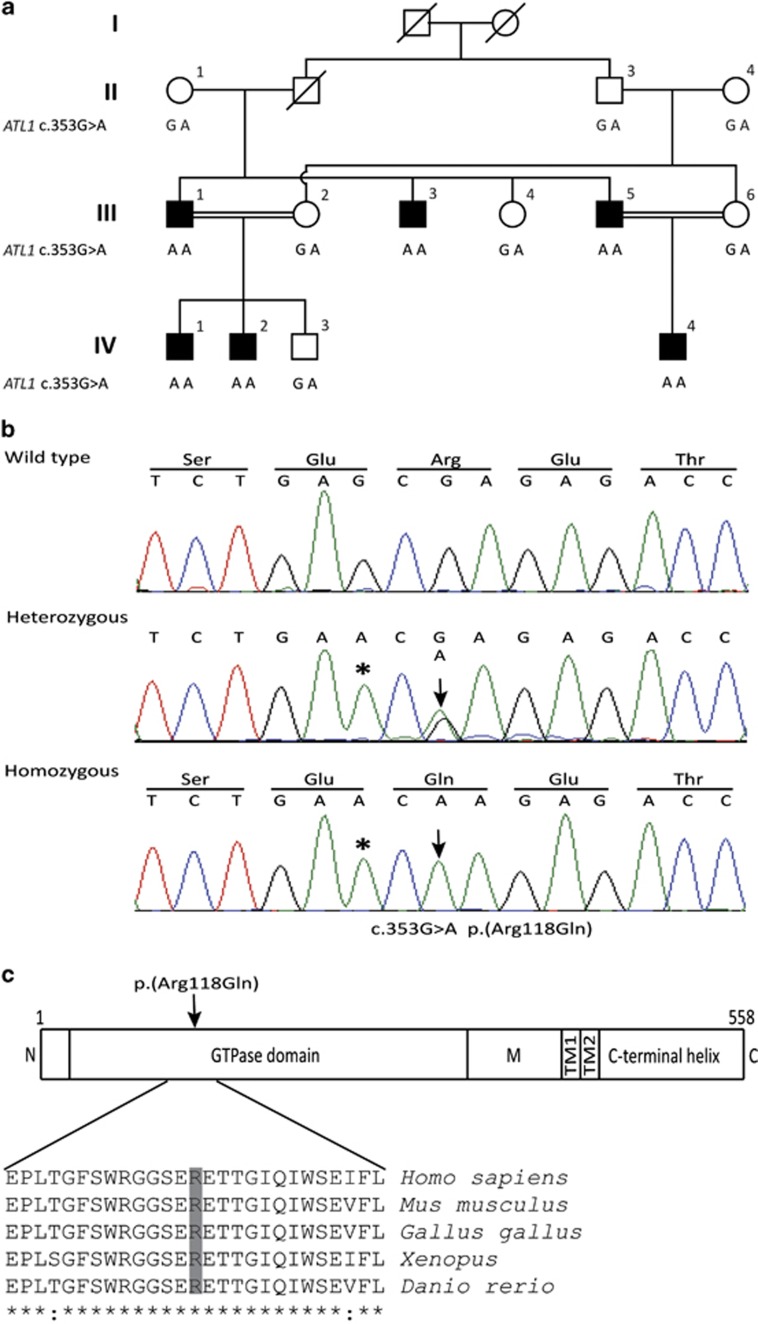

A consanguineous Pakistani family segregates pure HSP in six males in two generations. Owing to consanguinity, both autosomal dominant and recessive inheritance seemed possible (Figure 1a). The clinical onset was before 2 years of age (y.o.a.) with spastic gait and toe walking. Symptoms progressed slowly with bilateral spasticity of the lower limbs, brisk reflexes, reduced vibration sensation, peripheral numbness and tinglings, urinary bladder hyperactivity, scoliosis and pes cavus (Table 1). Cognitive functions were normal and the upper limbs were unaffected. Individuals III:1 and III:5 acquired walking assistance before attaining the age of 10 years. The affected members were between 3 and 45 years of age upon investigation (Table 1). Two affected brothers (III:3 and III:5) and their healthy sister (III:6) were available for brain and spinal cord magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electromyography (EMG). The NCS and EMG assessments were normal and without signs of neuropathy or myopathy in the three individuals. The MRI revealed mild foraminal stenosis at the cervical level in the affected individuals III:3 and III:5 interpreted as secondary to scoliosis. No MRI abnormalities were found in the healthy individual III:6 (Table 1). Clinical investigations of five healthy first-degree relatives (II:1, III:2, III:4, III:6 and IV:3) to affected individuals showed normal gait without deformities of the lower limbs (Table 1). The three family members in generation II were investigated at 66–75 y.o.a. and they had a normal neurological status. One healthy female (ind. III:6) showed a slightly impaired distal vibration sensation in lower limbs/malleoli at 36 y.o.a. Informed written consent was obtained from all individuals or their legal guardians, and the study was approved by the local ethical committee, National Institute for Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering, Faisalabad, Pakistan.

Figure 1.

Pedigree of the family segregating HSP and analysis of the ATL1 mutation. (a) The consanguineous family consists of two loops with two first-cousin marriages and six male individuals affected by pure HSP (filled symbols). The genotype at cDNA position 353 of ATL1 is shown below each symbol. Affected individuals are homozygous for the c.353G>A p.(Arg118Gln) mutation, whereas seven heterozygous family members are asymptomatic. The two females II:1 and II:4 are distantly related, but the precise relationship was unclear. (b) Sequence chromatogram showing part of ATL1 exon 4 (NM_001127713.1) obtained from a healthy control (top), individual III:6 (middle) and the affected individual III:1 (bottom). The ATL1 mutation c.353G>A p.(Arg118Gln) is indicated by an arrow. The asterisk denotes a synonymous SNP (rs1060197) with allele frequencies 0.19/0.81 (dbSNP) and without predicted effects. (c) Relative position of the p.(Arg118Gln) substitution in the GTPase domain of the atlastin-1 protein (top) and degree of conservation of the Arg118 residue (shaded) across different species. N, N-terminus; M, middle domain; TM, transmembrane domains.

Table 1. Clinical features of the family segregating an ATL1 mutation and autosomal recessive SPG3A.

| Individual | II:1 | II:3 | II:4 | III:1 | III:2 | III:3 | III:4 | III:5 | III:6 | IV:1 | IV:2 | IV:3 | IV:4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | wt/m | wt/m | wt/m | m/m | wt/m | m/m | wt/m | m/m | wt/m | m/m | m/m | wt/m | m/m |

| Age (years) | 66 | 75 | 70 | 45 | 35 | 31 | 32 | 43 | 32 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| Sex | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | M | M | M |

| Age at disease onset (years) | − | − | − | 1 | − | 1 | − | 1 | − | 1 | 1 | − | 1 |

| Spastic gait | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Difficulty in walking | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| LL spasticity | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| UL spasticity | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Scoliosis | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hyperactive urinary bladder | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Pes cavus | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Babinski reflex | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Clonus | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Radicular pain | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Excessive tingling | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Numbness | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Muscle tone | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Cognitive dysfunction | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Walking assistance | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Vibration sensation (peripheral) | Normal | Normal | Normal | Decreased | Normal | Decreased | Normal | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | NI | NI |

| Peripheral sensation | Normal | Normal | Normal | Decreased | Normal | Decreased | Normal | Normal | Normal | Decreased | Decreased | NI | NI |

| Pain perception (peripheral) | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Decreased | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | NI | NI |

| Reflexes of lower extremities | Normal | Normal | Normal | Hyper-reflexia | Normal | Hyper-reflexia | Normal | Hyper-reflexia | Normal | Hyper-reflexia | Hyper-reflexia | NI | NI |

| Paresthesia | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | NI | NI |

| EMG findings | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | Normal | NI | Normal | Normal | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| NCS findings | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | Normal | NI | Normal | Normal | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Brain MRI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | Normal | NI | Normal | Normal | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| Cervical Foraminal Stenosis (MRI) | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | + | NI | + | − | NI | NI | NI | NI |

Genetic analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood. The ambiguous mode of inheritance and the genetic heterogeneity in HSP prompted us to perform whole-exome sequencing conducted on DNA from two affected individuals (III:3 and IV:2). DNA was sonicated (Covaris S2, Covaris, Inc., Woburn, MA, USA) and fragment libraries were constructed using the AB Library Builder System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) followed by target enrichment according to the manufacturer's protocols (Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon v4 kit, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Exome capture was conducted with biotinylated RNA baits for 24 h followed by extraction using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. Captured DNA was amplified by emulsion PCR (EZ Bead System, Life Technologies) and sequenced on the SOLiD5500xl system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), generating over 100 million reads of 75 bp length for each sample. Alignment of reads to the human reference sequence (hg19 assembly) and variant detection was performed using v2.1 of the LifeScope software (Life Technologies). SNPs and indel data was stored in an in-house exome database together with variant annotation information obtained from ANNOVAR16 and dbSNP135. Custom R scripts were used to identify potentially damaging variants shared between the two patients while absent in any of the other ∼400 exomes in our in-house database. Bidirectional Sanger sequencing (Applied Biosystems BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit, Applied Biosystems) on a 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) was used for segregation analysis of the ATL1 and C14orf183 missense variants c.353G>A and c.388A>G, respectively, as well as for sequencing of the coding regions of DDHD1 and AP4S1 genes. Sequence analysis was performed using the Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). CytoScan high-density (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) array was performed on DNA from individual IV:2 for the analysis of copy number variations (CNVs) and homozygous regions. The array data was analyzed by using computer software Chromosome Analysis Suite version 1.2 (Affymetrix) loaded with Netaffx annotation (hg19/na32) files.

Results

Clinical investigations and family history revealed an early onset and pure form of HSP in six family members. The two affected family members III:3 and IV:2 were analyzed using WES and quality check of the aligned dataset showed that, for both individuals, ∼85% of the targeted exons were covered with at least 1X on average, whereas 80% were covered by 20X or more. We then searched for shared variants in the two individuals, and we identified 76 heterozygous or compound heterozygous non-synonymous nucleotide substitutions (data not shown) none of which were localized in genes associated with HSP. One nonsense mutation was identified in heterozygous state the PAFAH2 gene (c.C103T, p.(Arg35Ter)) encoding platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase 2 but the variant did not segregate with HSP in the family. We therefore decided to filter for homozygous variants. This revealed only two non-synonymous single-nucleotide variants including c.353G>A, p.(Arg118Gln) in ATL1 (NG_009028.1; NM_001127713.1; Figure 1b) and c.388A>G, p.(Ser130Gly) in C14orf183 (NM_001014830.1) separated by ∼0.5 Mb on chromosome 14q22. Based on the previous association of ATL1 mutations with HSP and the absence of other candidate variants, we considered ATL1 c.353G>A as a plausible genetic cause for the disease.

Sanger sequencing revealed that all six affected individuals are homozygous for the ATL1 mutation, whereas seven asymptomatic family members are heterozygous (Figure 1a). The c.353G>A variant is located in exon 4 and alters a highly conserved residue in a region encoding the GTPase domain of atlastin-1 (Figure 1c). The resulting amino-acid substitution replaces a positively charged arginine for the neutral glutamine predicted to be damaging by Polyphen-2, SNPs&GO, SIFT and Mutation taster (Scores: 1, 0.54, 0.005 and 0.99, respectively). The mutation was excluded in 200 ethnically Pakistani control chromosomes and it is not present in the EVS data release (ESP6500SI-V2) on the Exome Variant Server, NHLBI GO Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), Seattle, WA, USA (URL: http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) when accessed on August 2013.

The C14orf183 gene, spanning the second missense variant c.388A>G, p.(Ser130Gly), encodes a putative and uncharacterized protein. Similar to the ATL1 variant, the c.388A>G transition was not reported in available databases and it was found to segregate with HSP in the family. However, the C14orf183 gene has no orthologs reported from mouse (Mus musculus), chicken (Gallus gallus), frog (Xenopus) or zebrafish (Danio rero), indicating a low degree of evolutionary conservation. Furthermore, the prediction score for the c.388A>G transition p.(Ser130Gly) was 0.87 using Polyphen-2.

The CytoScan high-density array analysis of ind. IV:2 confirmed a large homozygous region on chromosome 14q extending from position 25918058 to 57498545 (∼32 Mb) without any indication of CNVs (Supplementary Figure 1). Notably, the DDHD1 and the AP4S1 genes, previously associated with autosomal recessive HSP,17, 18 are located within the homozygous region in individual IV:2. However, no mutations were detected by Sanger sequencing of all coding regions of the DDHD1 and the AP4S1 genes in two affected family members. The novel ATL1 variant reported in this study is deposited in the LOVD ATL1 gene database (http://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes/ATL1) under the accession number NM_001127713.1.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that heterozygous ATL1 mutations are associated with a spectrum of phenotypes ranging from ‘pure' to ‘complicated' forms of SPG3A,9, 10, 19 variable age of onset14, 20 and gender-related penetrance in some families.15 The identification of ATL1 mutation in autosomal dominant HSN1D21 further illustrates the clinical variability associated with ATL1 mutations.22 The family investigated herein segregates ‘pure' HSP compatible with both autosomal recessive and dominant inheritance and, strikingly, only males are affected. The extensive genetic heterogeneity in HSP prompted us to perform WES on two affected individuals. The genetic analysis revealed that all affected family members are homozygous for a novel ATL1 missense variant c.353G>A, p.(Arg118Gln) encoding a highly conserved residue in the GTPase domain. The predicted damaging effect of c.353G>A and the absence of other sequence variants in known HSP genes covered by WES supported the homozygous mutation as a plausible cause of the disease. The clinical presentation in affected individuals is consistent with SPG3A and an autosomal recessive inheritance is further supported by the investigation of seven healthy family members shown to be heterozygous carriers for the mutation. Clinical and neurophysiological investigations confirmed normal findings with the exception of one carrier female with subclinical and reduced vibration sensation at 32 y.o.a. Three heterozygous and asymptomatic carriers, two females and one male, in our study are >65 y.o.a., indicating that symptoms of HSP from one ATL1 c.353G>A allele are not developed late in life. In line with this observation, we did not find support for a gender-related penetrance in heterozygotes, although the number of individuals is very low.

At ∼0.5 Mb from the ATL1 gene on chromosome 14q, within the homozygous region shared by affected family members, we identified an additional novel missense variant in the C14orf183 gene. The C14orf183 gene encodes a putative and yet uncharacterized protein without known phenotypic associations and function. Furthermore, the gene shows a relatively low degree of evolutionary conservation, and the predicted damaging effect of the C14orf183 variant was not as strong as for the ATL1 variant. Thus, it is unlikely that the C14orf183 variant c.388A>G causes the HSP phenotype in our family.

The clinical variability and the absence of clear genotype–phenotype correlations for ATL1 mutations are intriguing. SPG3A is predominantly caused by missense substitutions, and it has been suggested that the pathogenic mechanism is mediated by a gain-of-function mechanism23 that manifests differently dependent on the position of the mutation, gene modifiers and environmental factors, possibly in combination. In our family, a simple mechanistic interpretation is that the early and consistent clinical onset (<2 y.o.a.) is because of an additive effect of two mutated alleles. However, the precise effect of the _ATL1_ c.353G>A variant will require further analysis, for example, by expressing the mutated allele in model systems. Interestingly, alternate inheritance patterns related to an additive effect of biallelic mutations have been observed in families segregating another type of SPG, namely SPG7. Biallelic paraplegin mutations in SPG7 cause spastic paraparesis, cerebellar atrophy and optic neuropathy, whereas heterozygous mutations appear to be a susceptibility factor for late onset neurodegenerative disorders or optic neuropathy.24 Thus, paraplegin mutations may cause both autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disease albeit with different clinical expressions.

The HSPs comprise a large number of clinically and genetically heterogeneous of neuropathies with all possible inheritance patterns. This constitutes a diagnostic challenge further complicated by clinical overlaps between types of HSPs.12 Our study shows that a biallelic ATL1 mutation can mediate early onset SPG3A and adds to the genetic complexity of HSP. Genetic studies show that ∼20% of cases reported with HSP are negative for mutations, and one potential explanation could be misinterpretation of the inheritance pattern when selecting candidate genes.15 Our data demonstrate that ATL1 mutations can be taken into account in families with nondominant and even recessive inheritance of HSP. WES or complete gene panels in order to target all known SPG loci are thus preferred methods for improved genetic diagnosis in HSP that circumvents a selection bias based on inheritance patterns.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the family members for their cooperation in the study and we are indepted to Dr Atle Melberg for discussions and to Uppsala Genome Center. This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (K-2013-66X-10829-20-3), Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala University and the Science for Life Laboratory. TNK was supported by Higher Education Commission of Pakistan, and JK was supported by the Swedish Society for Medical Research.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure

Supplementary Figure Legend

References

- Fink JK, Heiman-Patterson T, Bird T, et al. Hereditary spastic paraplegia: advances in genetic research. Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia Working group. Neurology. 1996;46:1507–1514. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterer J, Loscher W, Quasthoff S, Wanschitz J, Auer-Grumbach M, Stevanin G. Hereditary spastic paraplegias with autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked, or maternal trait of inheritance. J Neurol Sci. 2012;318:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon MJ, Lee ST, Kim JW, Sung DH, Ki CS. Clinical and genetic analysis of a Korean family with hereditary spastic paraplegia type 3. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2010;40:375–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainier S, Hedera P, Alvarado D, et al. Hereditary spastic paraplegia linked to chromosome 14q11-q21: reduction of the SPG3 locus interval from 5.3 to 2.7 cM. J Med Genet. 2001;38:E39. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.11.e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt J, Ballo R, Sachs B, Moosa A. X-linked spastic paraplegia: evidence for homogeneity with a variable phenotype. Clin Genet. 1989;35:116–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1989.tb02915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourani R, El-Hajj T, Barada WH, Hourani M, Yamout BI. MR imaging findings in autosomal recessive hereditary spastic paraplegia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:936–940. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppen LD, Leppert MF, O'Connell P, et al. Etiological heterogeneity in X-linked spastic paraplegia. Am J Hum Genet. 1987;41:933–943. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schule R, Schols L. Genetics of hereditary spastic paraplegias. Semin Neurol. 2011;31:484–493. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durr A, Camuzat A, Colin E, et al. Atlastin1 mutations are frequent in young-onset autosomal dominant spastic paraplegia. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1867–1872. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.12.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namekawa M, Ribai P, Nelson I, et al. SPG3A is the most frequent cause of hereditary spastic paraplegia with onset before age 10 years. Neurology. 2006;66:112–114. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191390.20564.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico A, Tessa A, Sabino A, Bertini E, Santorelli FM, Servidei S. Incomplete penetrance in an SPG3A-linked family with a new mutation in the atlastin gene. Neurology. 2004;62:2138–2139. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000127698.88895.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedera P.Spastic Paraplegia 3A. (Updated 9 February, 2012)In: Pagon RA AM, Bird TD, et al. (eds).: GeneReviews™ (Internet) Seattle, WA, USA: University of Washington; 1993–2013. Available athttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45978/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlacchio A, Montieri P, Babalini C, Gaudiello F, Bernardi G, Kawarai T. Late-onset hereditary spastic paraplegia with thin corpus callosum caused by a new SPG3A mutation. J Neurol. 2011;258:1361–1363. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-5934-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Alvarado D, Rainier S, et al. Mutations in a newly identified GTPase gene cause autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia. Nat Genet. 2001;29:326–331. doi: 10.1038/ng758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga R-E, Schüle R, Fadel H, et al. Do not trust the pedigree: reduced and sex-dependent penetrance at a novel mutation hotspot in ATL1 blurs autosomal dominant inheritance of spastic paraplegia. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:860–863. doi: 10.1002/humu.22309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abou Jamra R, Philippe O, Raas-Rothschild A, et al. Adaptor protein complex 4 deficiency causes severe autosomal-recessive intellectual disability, progressive spastic paraplegia, shy character, and short stature. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:788–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesson C, Nawara M, Salih MA, et al. Alteration of fatty-acid-metabolizing enzymes affects mitochondrial form and function in hereditary spastic paraplegia. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:1051–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova N, Claeys KG, Deconinck T, et al. Hereditary spastic paraplegia 3a associated with axonal neuropathy. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:706–713. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.5.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter SM, Engel W, Neumann LM, Kunze J, Neesen J. Novel mutations in the Atlastin gene (SPG3A) in families with autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia and evidence for late onset forms of HSP linked to the SPG3A locus. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:98. doi: 10.1002/humu.9205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelly C, Zhu PP, Leonardis L, et al. Targeted high-throughput sequencing identifies mutations in atlastin-1 as a cause of hereditary sensory neuropathy type I. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarano V, Mancini P, Criscuolo C, et al. The R495W mutation in SPG3A causes spastic paraplegia associated with axonal neuropathy. J Neurol. 2005;252:901–903. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0768-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez V, Sanchez-Ferrero E, Beetz C, et al. Mutational spectrum of the SPG4 (SPAST) and SPG3A (ATL1) genes in Spanish patients with hereditary spastic paraplegia. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:89. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-10-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebe S, Depienne C, Gerber S, et al. Spastic paraplegia gene 7 in patients with spasticity and/or optic neuropathy. Brain. 2012;135:2980–2993. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure

Supplementary Figure Legend