Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Among Adolescents and Young Adults (original) (raw)

Abstract

Introduction:

Understanding why young people try and stop electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use is critical to inform e-cigarette regulatory efforts.

Methods:

We conducted 18 focus groups (N = 127) in 1 middle school (MS), 2 high schools (HSs), and 2 colleges in Connecticut to assess themes related to e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation. We then conducted surveys to evaluate these identified themes in 2 MSs, 4 HSs, and 1 college (N = 1,175) to explore whether reasons for e-cigarette experimentation and/or discontinuation differed by school level or cigarette smoking status.

Results:

From the focus groups, we identified experimentation themes (i.e., curiosity, flavors, family/peer influence, easy access, and perceptions of e-cigarettes as “cool” and as a healthier/better alternative to cigarettes) and discontinuation themes (i.e., health concerns, loss of interest, high cost, bad taste, and view of e-cigarettes as less satisfying than cigarettes). The survey data showed that the top reasons for experimentation were curiosity (54.4%), appealing flavors (43.8%), and peer influences (31.6%), and the top reasons for discontinuation were responses related to losing interest (23.6%), perceiving e-cigarettes as “uncool” (16.3%), and health concerns (12.1%). Cigarette smokers tried e-cigarettes because of the perceptions that they can be used anywhere and to quit smoking and discontinued because they were not as satisfying as cigarettes. School level differences were detected.

Conclusions:

E-cigarette prevention efforts toward youth should include limiting e-cigarette flavors, communicating messages emphasizing the health risks of use, and changing social norms surrounding the use of e-cigarettes. The results should be interpreted in light of the limitations of this study.

Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are devices that use an inhalation-activated element to vaporize a nicotine solution. E-cigarettes are rapidly gaining popularity among adolescents1–4 and young adults5,6 despite a paucity of research on safety and health effects. Among a college sample in North Carolina, 4.9% reported ever use and 1.9% reported past 30-day use in 2009.6 Data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey indicated that lifetime use of e-cigarettes among middle-school (MS) and high-school (HS) students increased from 3.3% to 6.8% between 2011 and 2012, with HS students using at higher rates (4.7% in 2011, 10.0% in 2012).2 Results from a large survey study conducted in Connecticut in 2013 found that 3.5% of MS and 25.2% of HS students reported lifetime use of e-cigarettes.7

While e-cigarette use is undeniably on the rise among youth, the extent to which e-cigarette use will result in harm is under debate. Tobacco control and public health advocates are concerned that e-cigarettes may serve as “gateway” to combustible tobacco products and encourage nicotine addiction and/or dual tobacco use among youth.8 In contrast, e-cigarette proponents view e-cigarettes as a valuable harm-reduction tool for current cigarette smokers (CCS).9 Consistent with this view, e-cigarettes are promoted through the media as a safer, more fashionable alternative to cigarettes.10,11 The contradictory messages about the potential risks and benefits of e-cigarettes are likely to be confusing to adolescents and young adults. In the absence of clear negative health messages about e-cigarettes, it seems likely that opinions about e-cigarettes, and consequently young people’s decision whether or not to initiate e-cigarette use, are influenced by factors including the pervasive marketing of e-cigarettes through social media (e.g., YouTube and Twitter) as a sexy and safe alternative to tobacco cigarettes, the appeal of the “high tech” nature of e-cigarettes, and the availability of many flavors (e.g., fruit and candy). These influences also may discourage e-cigarette cessation among youth who currently use e-cigarettes. The extent to which these messages affect young people’s decision to use or not use e-cigarettes is unknown. Having a better understanding of the factors that guide adolescents’ and young adults’ decisions to try and stop e-cigarette use can be critical in informing the _Food and Drug Administration_’s efforts to effectively regulate e-cigarettes.12,13

A recent study among adult lifetime e-cigarette users found that the top reasons for trying e-cigarettes were curiosity, influence of family or friends, and to quit smoking, and the top reasons for discontinuation were “just experimenting,” “e-cigarettes did not feel like smoking cigarettes,” and dissatisfaction with the taste.14 Whether these reasons are also important determinant of adolescents’ and young adults’ decisions remain unexplored. Components of e-cigarettes, such as the availability of various flavors, may be more appealing to youth.

Thus, the goal of this study was to use qualitative and quantitative studies to assess reasons for e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among adolescents and young adults. We evaluated whether these reasons differed by cigarette smoking status and school setting (MS, HS, and college). We first conducted focus groups with adolescents and young adults to explore the themes related to e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation. We then assessed the importance of these empirically derived themes in larger groups of MS, HS, and college students using cross-sectional surveys. We hypothesized that cigarette smokers’ reasons to try and to discontinue e-cigarettes will be influenced by comparisons of e-cigarettes to conventional cigarettes. Based on the findings from self-selected adult sample of predominantly cigarette smokers recruited on e-cigarette discussion forums and on conventional cigarette smoking cessation Web sites,15 we hypothesized that adolescent and young adult smokers may experiment with e-cigarettes to cope with tobacco cravings and to smoke in situations where cigarette smoking is prohibited. Discontinuation reasons may include lack of reduction in cigarette cravings by e-cigarettes and relapse to cigarette smoking. Based on prior evidence,16 we hypothesized that adolescents and young adults frequently would cite the availability of flavors and innovative product design as factors motivating e-cigarette use. Based on some health expert concerns about the known and unknown health risks of e-cigarettes,17 we hypothesized that a reason for e-cigarette discontinuation may be related to health concerns.

Methods

Procedures

We first conducted 18 focus groups (N = 127) with four to eight (M = 7.11, SD = 1.24) participants in each group in one MS, two HSs, and two colleges in New Haven County, CT, in November 2012–April 2013. We then conducted school-wide surveys in a larger sample of adolescents in 4 HSs (N = 3,614—School 1: n = 877; School 2: n = 1,210; School 3: n = 527; School 4: n = 1,000) and 2 MSs (N = 1,166—School 1: n = 430; School 2: n = 736) in November 2013 and one public university (N = 625) in May 2014.

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yale University, the local school boards, and the participating schools and colleges. Passive parental consent was obtained in MSs and HSs. We invited six HSs from different District Reference Groups (DRGs: school groupings based on indicators of socioeconomic status, financial needs, and school enrollment) in Connecticut to participate. Of these, four HSs agreed to participate. We then invited four MSs from the DRGs of the participating HSs, and of these, two MSs agreed to participate. Two large public universities in Connecticut participated in the focus group study and of the two, one participated in the survey study.

Approximately 2 weeks prior to each study, information sheets were mailed to the parents detailing the study, and parents were instructed to contact the research staff if they did not want their child to participate. All participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the study and limits to confidentiality. Written assent (<18 years old) or consent (≥18 years old) was obtained in focus groups, and the participation in the survey was regarded as assent/consent.

Focus Group Procedures

The MS and HS focus group participants were recruited using flyers and active recruitment sessions during lunch time. Staff liaisons within each school facilitated recruitment by making announcements during lunch and homeroom periods and coordinating the presence of the research staff to recruit on school premises. College students were recruited via business cards that described the study and provided a link and a Quick Response (QR) code that directed students to the study Web site for screening questions (i.e., demographic information, cigarette use, and available times to attend the focus groups). All interested participants who were willing to participate in a 1-hr-long focus groups about tobacco products were eligible to participate. HS and college students were also asked as part of the screener, “How often do you smoke cigarettes?” (response options were “everyday,” “occasionally,” “I quit,” “I never smoked”). Those who indicated smoking “occasionally” or “everyday” were considered cigarette smokers, and those who indicated “I never smoked” were considered nonsmokers. The HS and college groups were stratified by cigarette smoking status and gender. The MS groups were stratified by gender only due to low rates of cigarette smoking. One female college student who participated in a smoking focus group revealed that she was, in fact, a nonsmoker. As such, her contributions were not considered for data analysis.

The focus groups were held after school for MSs and HSs and during lunch and evening times in colleges. Participants were provided with refreshments prior to the focus groups and compensated for their participation ($25–$50).

Doctoral level (PhD and MD) facilitators led the semi-structured focus groups and assessed students’ perceptions of modified-risk tobacco products, including e-cigarettes. The groups discussed knowledge about e-cigarettes, motivations to use, comparative perceptions to cigarettes, social norms surrounding use, perceptions of risk, and marketing. All focus groups were debriefed on the risks of tobacco use and nicotine exposure at the conclusion of the group. A study staff member took detailed notes, and all groups were voice recorded. An independent transcriber subsequently transcribed the voice recordings, which were then uploaded to ATLAS.ti.7 for data analysis.

Survey Procedures

The entire student body in each school (two MSs and four HSs) completed the paper-and-pencil surveys during advisories/homerooms, with the exception of 12 adolescents whose parents refused permission. The response rates based on the attendance on the day of the survey administration were high (87.1% HS; 94.1% MS). The surveys were distributed by teachers who informed the students that participation was voluntary and surveys were anonymous. These instructions also were repeated on the cover sheets of the survey. Research staff was available at the school at the time of the survey to answer questions. Students were given pens for participating.

To recruit college students, index cards with the study information and a link and a QR code that directed students to the online survey were distributed to randomly selected classes, as well as to the students in the student union during free periods. Students were also provided with an opportunity to complete the survey using the study laptop in the student union. All participants were enrolled in a chance to win $50 gift cards for their participation.

Focus Group Methods

Participants

The focus group sample was 56.7% Caucasian, 20.5% Black, 10.2% Hispanic, 3.9% Asian, and 8.7% other or multiple race/ethnicity. The mean age in college was 19.97 (SD = 2.03), HS was 16.06 (SD = 1.33), and MS was 13.0 (SD = 0.73).

Focus Group Data Analysis

We analyzed the focus group transcripts using framework analysis18 and focused on responses to the following questions: “What have you heard about e-cigarettes?” “Tell us about the first time you used an e-cigarette,” and “Why do you think people your age would use e-cigarettes?” Participants who indicated that they had ever tried e-cigarettes were coded as “lifetime e-cigarette users.” Responses related to personal reasons for e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation were probed further for clarification and to evoke greater detail into participants’ narrative.

Two members of the research team reviewed all transcripts during an initial inductive analysis to identify relevant coding themes across focus groups. Following this initial procedure, the corresponding verbatim transcripts related to e-cigarette themes of “experimentation,” “reasons for personal use,” “interested/not interested in using,” and “perceptions of others’ using” were selected for further analysis using ATLAS.ti.7. We conducted a deductive analysis in which three independent coders reviewed the selected transcripts to identify themes related to e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation by school setting and cigarette smoking status among students who reported ever trying an e-cigarette. Discrepancies between the coders were amended until consensus was reached.

Focus Group Results

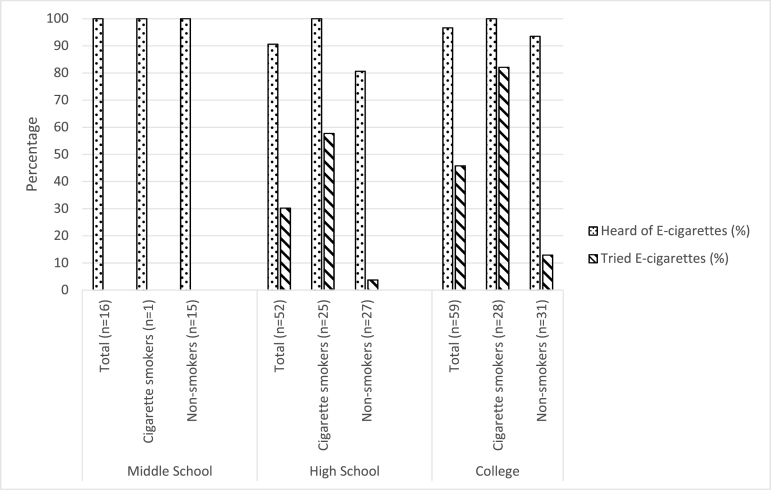

Almost all (94.5%) participants had heard about e-cigarettes and 33.9% had tried an e-cigarette. Awareness of e-cigarettes did not differ across school setting (χ2(1, N = 127) = 3.13, p = .21) or by gender (χ2(1, N = 127) = 0.34, p = .56). Males and females did not differ on lifetime e-cigarette use (χ2(1, N = 127) = 0.56, p = .46), but college students were more likely than HS students to be lifetime e-cigarette users (χ2(1, N = 127) = 12.15, p = .002; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

E-cigarette knowledge and use among focus group participants separated by school setting and cigarette smoking status.

Table 1 depicts the themes related to e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation and example quotations. None of the MS participants had tried an e-cigarette, so they did not discuss reasons for e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation; thus, they were not included in this analysis.

Table 1.

Focus Group Themes and Example Narratives (N = 127)

| Overall themes | Subsample endorsing the specific themes | Specific themes | Example narrative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reasons for experimentation among lifetime e-cigarette users | HS smokers | Influence of family and friendsa | “My friend used them, my closest friend actually for some reason bought one. I don’t know why, he never smoked or anything and he just got one, right, and he’s like sharing with everyone. So as long as he was sharing it with everyone, I tried it.” High school, male smoker (#80) |

| HS nonsmokers | To be “cool” | ||

| College smokers | Curiosity | ||

| College nonsmokers | Readily available | ||

| Flavors | |||

| HS smokers | Comparison to cigarettes | “Like I started it because I wanted to be able to breathe. Like I was walking up stairs and like was so out of breath and like I hated it. So I got this (e-cigarette) and that’s gone away. I can breathe again and there’s also cost benefits. So it’s kind of a win, win.” College, male smoker (#26) | |

| College smokers | Healthiera | ||

| Less harsh | |||

| Cheaper | |||

| Smells better | |||

| More convenient | |||

| Can hide it | |||

| Use it indoors | |||

| Reasons for discontinuation among lifetime e-cigarette users | HS smokers | Losing interest | “I had a friend who made me try hers, like you don’t get the same feeling like when you smoke an actual cigarette. I hung on that thing for hours and I’m just like I need a cigarette this isn’t doing it for me, it’s not, it’s almost like a junkie when you need a cigarette like I waitress, when I need a cigarette, I need a cigarette. I don’t need an electronic cigarette, I need an actual cigarette so it just doesn’t do it for me.” College, female smoker (#12) |

| HS nonsmokers | Negative physical effects (e.g., light headed) | ||

| College smokers | |||

| College nonsmokers | |||

| HS smokers | Bad taste | ||

| College smokers | High cost | ||

| Less satisfying than cigarettesa |

Reasons for Experimentation Among Lifetime E-cigarette Users

Both HS and college lifetime e-cigarette users, regardless of cigarette smoking status, discussed themes that included curiosity and the fact that e-cigarettes are readily available at malls and convenience stores. A number of participants reported having friends or family members (e.g., parents and siblings) who had used e-cigarettes to quit smoking or as an alternative to cigarettes. Several participants reported that they had been offered an e-cigarette by a friend or a family member.

Experimentation was also related to e-cigarettes perceived as being “cool”; specifically, the look and design of the e-cigarettes were considered appealing, and users were viewed to have a positive social image. HS cigarette smokers reported experimenting because of appealing flavors and to do “smoke tricks” with the e-cigarette vapor.

In addition, HS and college cigarette smokers thought that e-cigarettes were a better alternative to cigarettes. Relative to cigarettes, cigarette smokers described e-cigarettes as healthier (e.g., “doesn’t upset your stomach”), less harsh, cheaper, and smelling better. Several cigarette smokers reported that using e-cigarettes promoted the restoration of health functions previously compromised by cigarette smoking (e.g., “can breathe better”). Convenience factors were also mentioned as reasons for experimentation including being able to use e-cigarettes indoors where cigarette smoking is prohibited (e.g., movie theaters and at school), avoiding having to smoke outdoors in inclement weather, not having to use lighters or deal with ashes, and being able to hide e-cigarette use from parents/teachers because they are odorless. They also expressed that odorless e-cigarette vapor was preferable to malodorous cigarette smoke. Furthermore, they perceived that e-cigarettes can be used to quit smoking.

Reasons for Discontinuation Among Lifetime E-cigarette Users

Both HS and college cigarette smokers and nonsmokers discussed losing interest in e-cigarettes as a reason for discontinuation. Other themes included negative physical effects (“getting lightheaded”). HS and college cigarette smokers also reported discontinuing because of the bad taste (“tastes like chemicals”), the high cost, and the perception that e-cigarettes are less satisfying than cigarettes.

Survey Methods

Measures

“Lifetime e-cigarette users” were defined as respondents who responded “yes” to “Have you tried e-cigarettes?” Those who responded “no” were coded as “Never e-cigarette users.” “Never cigarette smokers (NCS)” were defined as respondents who indicated that they had never tried cigarette smoking to “How old were you when you first tried a cigarette, even one or two puffs?” “Ever cigarette smokers (ECS)” provided a valid age of smoking onset, but they did not report smoking in the past 30 days. “CCS” reported that they had smoked at least one cigarette in the past 30 days.

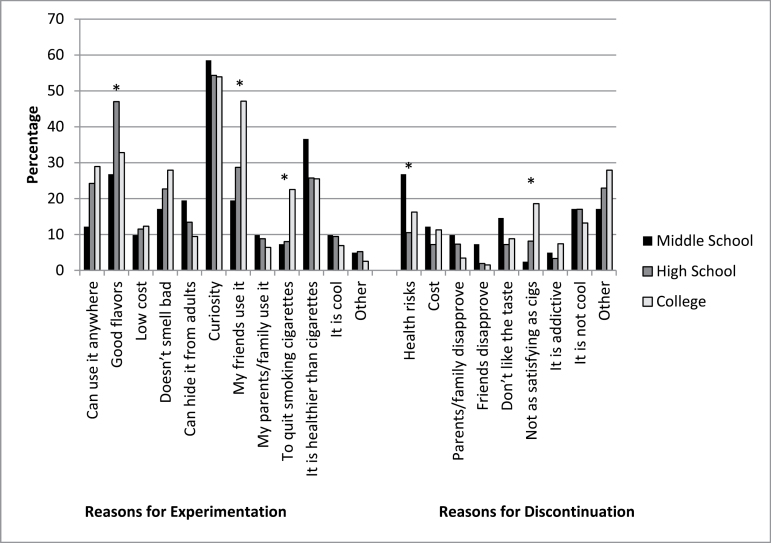

Motives for e-cigarette experimentation were assessed by “Why did you try an e-cigarette?” and discontinuation by “If you tried an e-cigarette but stopped using it, why did you stop?” The response options for these questions were derived from the focus group data, and participants were instructed to select all applicable responses. Figure 2 and Table 2 list all response options.

Figure 2.

Reasons for e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation among middle-school, high-school, and college students. Note. *p ≤ .002.

Table 2.

Adjusted Multinomial Regression Models Examining the Reasons for E-cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Between Cigarette Smokers and Nonsmokers

| | OR (95% CI) | | | | ----------------------------------- | -------------------------------------- | -------------------------- | | Ever cigarette smokers (n = 332) | Current cigarette smokers (n = 393) | | | Reasons for experimentation | | | | Can use it anywhere | 2.18 (1.34, 3.55) | 4.43 (2.79, 7.03) | | Appealing flavors | 1.24 (0.87, 1.76) | 1.02 (0.77, 1.58) | | Low cost | 0.65 (0.34, 1.24) | 0.82 (0.45, 1.50) | | Doesn’t smell bad | 0.84 (0.51, 1.38) | 1.07 (0.66, 1.74) | | Can hide it from adults | 1.45 (0.80, 2.60) | 1.76 (1.00, 3.10) | | Curiosity | 1.27 (0.92, 1.75) | 1.08 (0.78, 1.49) | | My friends use it | 0.86 (0.61, 1.22) | 0.78 (0.55, 1.12) | | My parents/family use it | 1.66 (0.93, 2.98) | 1.44 (0.80, 2.60) | | To quit smoking cigarettes | 37.48 (4.96, 283.31) | 102.19 (13.81, 755.91) | | It is healthier than cigarettes | 1.01 (0.67, 1.53) | 0.78 (0.51, 1.19) | | It is cool | 0.52 (0.29, 0.95) | 0.88 (0.51, 1.51) | | Other | 0.94 (0.45, 1.95) | 1.02 (0.51, 2.04) | | Reasons for discontinuation | | | | Health risks | 0.82 (0.52, 1.29) | 0.44 (0.26, 0.75) | | Cost | 1.45 (0.82, 2.56) | 1.27 (0.71, 2.28) | | Parents/family disapprove | 0.99 (0.56, 1.75) | 0.46 (0.23, 0.94) | | Friends disapprove | 1.34 (0.48, 3.70) | 0.67 (0.17, 2.73) | | Don’t like the taste | 0.60 (0.33, 1.09) | 0.72 (0.40, 1.27) | | Not as satisfying as cigarettes | 3.04 (0.76, 12.12) | 47.78 (14.25, 160.17) | | It is addictive | 1.03 (0.47, 2.22) | 0.92 (0.39, 2.17) | | It is not cool | 0.85 (0.59, 1.24) | 0.23 (0.14, 0.38) | | Other | 0.74 (0.52, 1.06) | 0.34 (0.23, 0.51) |

Participants

The sample comprised 5,405 adolescents and young adults (1,166 MS [50.5% males], 3,614 HS [47.7% males], and 625 college [25.0% males]). They were Caucasians (81.1% MS; 66.4% HS; 67.8% college), Hispanics (6.2% MS; 13.2% HS; 8.6% college), Blacks (2.1% MS; 8.4% HS; 11.8% college), Asians (3.5% MS; 4.1% HS; 2.9% college), mixed race (3.9% MS; 5.2% HS; 5.4% college), and other race/ethnicity (1.7% MS; 1.7% HS; 3.0% college). The average age in MS was 12.18 (SD = 0.90), HS was 15.63 (SD = 1.20), and college was 22.12 (SD = 5.45). Data analyses were restricted to lifetime e-cigarette users (N = 1,157; MS: 3.5%, HS: 25.2%, and college: 32.6%).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated, and chi-square tests evaluated school level differences (i.e., MS, HS, and college) on all variables. Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied, and p < .002 was considered statistically significant for chi-square statistics. Adjusted multinomial logistic regression analyses evaluated the extent to which reasons for e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation (separate models) differed based on cigarette smoking status (dependent variable) controlling for gender, age, school level (MS, HS, and college), and race (Caucasian vs. non-Caucasian). Cigarette smoking status included NCS, ECS, and CCS.

Survey Results

Among lifetime e-cigarette users (N = 1,157), 37.3% were NCS (MS = 58.5%, HS = 41.8%, and college = 13.2%), 28.7% were ECS (MS = 24.4%, HS = 26.6%, and college = 38.7%), and 34.0% were CCS (MS = 17.1%, HS = 31.6%, and college = 48.0%).

The top three reasons for e-cigarette experimentation among lifetime e-cigarette users, regardless of cigarette smoking status and school level, were curiosity (54.4%), the availability of appealing flavors (43.8%), and friends’ influence (31.6%). Of “other” reasons (4.7%), experimenting with e-cigarettes to do “smoke tricks” was a common response. Chi-square tests showed school level differences in experimenting because of (a) appealing flavors (χ2(2, N = 1,157) = 18.63, p ≤ .001), (b) friends’ influence (χ2(2, N = 1,157) = 28.79, p ≤ .001), and (c) to quit smoking (χ2(2, N = 1,157) = 37.86, p ≤ .001). Specifically, compared to college students, HS students were more likely to experiment with e-cigarettes because of appealing flavors (47.0% vs. 32.8%, χ2(1, N = 1,116) = 13.61, p ≤ .001) and less likely to experiment with e-cigarettes to try to quit smoking (8.0% vs. 22.5%, χ2(1, N = 1116) = 37.02, p ≤ .001). College students were more likely than MS (47.1% vs. 19.5%, χ2(1, N = 245) = 10.60, p = .001) and HS (47.1% vs. 28.7%, χ2(1, N = 1,116) = 25.71, p ≤ .001) students to endorse friends’ influence for experimentation.

The top three reasons for discontinuation were “other” (23.6%), “uncool” (16.3%), and health risks (12.1%). “Other” responses mostly indicated loss of interest such as “I don’t like it” and “I just tried once.” Chi-square tests showed school level differences in discontinuing because of health risks (χ2(2, N = 1,157) = 13.67, p = .001) and the perception that e-cigarettes are less satisfying than cigarettes (χ2(2, N = 1,157) = 23.50, p ≤ .001). Compared to HS students, MS students were more likely to endorse health risks (26.8% vs. 10.5%; χ2(1, N = 953) = 10.46, p = .001). College students were more likely than HS students to endorse discontinuing because e-cigarettes were not as satisfying as regular cigarettes (18.6% vs. 8.1%; χ2(1, N = 1,116) = 20.41, p ≤ .001).

See Table 2 for the adjusted multinomial logistic regression results. Compared to NCS, ECS and CCS were more likely to experiment because e-cigarettes can be used anywhere (ECS: odds ratio [_OR_] = 2.18, CCS: OR = 4.43) and to quit smoking (ECS: OR = 37.48, CCS: OR = 102.19). Relative to NCS, CCS were more likely to experiment because of the ability to hide e-cigarettes from adults (OR = 1.76). Relative to NCS, CCS were more likely to discontinue due to perceptions that e-cigarettes are less satisfying than cigarettes (OR = 47.78) but were less likely to discontinue due to health risks (OR = 0.44), parents/family disapproval (OR = 0.46), perception that e-cigarettes are “uncool” (OR = 0.23), and other responses, mostly related to experimentation (OR = 0.34).

Discussion

We examined adolescents’ and young adults’ reasons for e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation in MS, HS, and college students in Connecticut. A strength of this study is the formative, qualitative examination through the use of focus groups to empirically derive reasons for e-cigarette experimentation and discontinuation, which then informed the development of subsequent cross-sectional surveys to assess these factors among large numbers of adolescents and young adults.

Recent evidence from adult lifetime e-cigarette users suggests that the top three reasons for initiation are curiosity, influence of friends or family, and for quitting smoking.14 Our results suggest that adolescents report similar reasons for experimentation. However, in addition, we also identified other factors including the availability of flavors and the ability to do smoke tricks. Availability of flavors was the second most endorsed reason following curiosity for experimentation, and school level differences showed that appealing flavors are particularly important to HS students. This finding illustrates that appealing e-cigarette flavors (e.g., candy) are particularly attractive to adolescents. We also identified new themes for experimentation among HS students, such as the ability to do “smoke tricks” using vapors from e-cigarettes. These findings suggest that youth appeal of e-cigarettes could also be reduced by eliminating visible vapors that can be used to do “smoke tricks” and restricting the availability of appealing flavors.

Not surprisingly, many of the observed themes related to e-cigarette experimentation reflected the themes used in marketing of e-cigarettes, such as the perceptions that e-cigarettes are safer and healthier than cigarettes.19 Our group has observed that MS and HS students have been exposed to the marketing of e-cigarettes in various locations, including gas stations, malls, magazines, and online sources.7 These views may also be promoted by the aggressive marketing of e-cigarettes on popular Web sites and via promotional video clips demonstrating how to use the products.20 These findings highlight the need to closely monitor how the marketing messages and outlets affect e-cigarette use patterns among youth.

Recent evidence also suggests that the top reasons for discontinuation among adult lifetime e-cigarette users were negative comparisons to cigarettes (i.e., e-cigarettes do not feel like cigarette smoking) and dissatisfaction with the taste of e-cigarettes.14 We also observed similar themes among adolescent and young adult smokers. However, adolescent and young adult lifetime e-cigarette users also reported that perceptions of e-cigarette use as being “uncool” and potential negative health concerns were the top reasons for discontinuation of use. These health concerns seem to more prominent among MS students. This suggests that early prevention efforts that highlight the health risks of e-cigarettes and nicotine addiction may be an effective prevention strategy for younger adolescents. Communicating accurate and effective health messages to youth is important given that unproven claims about e-cigarettes (e.g., they are a healthier alternative to cigarettes) are often used in the aggressive marketing in the United States.10,11 Taken together, e-cigarette prevention strategies may be effective if they decrease curiosity about e-cigarettes and attempt to change social norms surrounding e-cigarettes as being “uncool.”

We also detected differences by cigarette smoking status. Multinomial logistic regression analyses indicated that cigarette smokers (ever and current smokers), regardless of age, were more likely than nonsmokers to make comparisons to cigarettes for their reasons to experiment and to discontinue e-cigarette use. Cigarette smokers were more likely than non-cigarette smokers to experiment with e-cigarettes to quit smoking; however, the large confidence intervals surrounding this variable in the predictive model call into the question the stability of the findings, and future research is needed to determine how cigarette smoking is related to e-cigarette experimentation. Our data also indicate that despite CCS’ reports of experimenting with e-cigarettes to quit smoking, they still reported past-month cigarette smoking. CCS were also more likely than nonsmokers to use e-cigarettes indoors and to hide smoking from adults, suggesting that they may be using e-cigarettes to bypass smoke-free laws and to hide their use from authority figures. Although our findings suggest dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes rather than use of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation, longitudinal examinations using larger population-based data sources are needed to determine if adolescent smokers who experiment with e-cigarettes to quit smoking eventually transition to e-cigarette use only, quit all tobacco products, or continue dual use. Previous studies in adults have also shown that experimentation of e-cigarettes was not associated with plans to quit smoking21 or with successful quit attempts.22 However, a more recent study showed that daily use of e-cigarettes for at least 1 month was associated with quitting smoking among adult smokers.23 There is a critical need to develop a better understanding of the role of e-cigarettes in smoking cessation among youth.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of limitations. We sampled schools in southeastern Connecticut. Although we selected schools in different DRGs, the students may not generalize across different geographic regions and socioeconomic status. The cross-sectional nature of the survey and the focus groups preclude us from making causal statements.

In conclusion, we detected several important themes that provide insight into why adolescents and young adults experiment and discontinue e-cigarettes. We also identified unique themes that are relevant to cigarette smokers. Of concern, many e-cigarette users and nonusers held beliefs about e-cigarettes that were consistent with a range of unsubstantiated claims that frequently appear in e-cigarette advertisements (e.g., e-cigarettes can be used to quit smoking and are a healthy alternative to smoking). Given the current dearth of data regarding e-cigarette safety,24 strategic and effective health communication campaigns that demystify the product and counteract misconceptions regarding e-cigarette use are needed. These efforts should also include information about the effects of nicotine addiction as well as explicit statements that e-cigarettes have not been proven to be safer alternatives to conventional cigarettes or an effective means of smoking cessation.25 In order to reduce youth appeal, regulation efforts can include restricting the availability of e-cigarette flavors as well as visible vapors.

Funding

This study was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants P50DA009241, 1K12DA033012-01A1, and T32DA019426. The study sponsors had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Amanda Palmer for assisting with the focus group data collection.

References

- 1.Camenga DR, Kong G, Cavallo DA, et al. Alternate tobacco product and drug use among adolescents who use electronic cigarettes, cigarettes only, and never smokers. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:588–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control. Electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2012. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:729–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dutra LM, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among us adolescents: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:610–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee S, Kimm H, Yun JE, Jee SH. Public health challenges of electronic cigarettes in South Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2011;44:235–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pokhrel P, Little MA, Fagan P, Muranaka N, Herzog TA. Electronic cigarette use outcome expectancies among college students. Addict Behav. 2014;39:1062–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutfin EL, McCoy TP, Morrell HER, Hoeppner BB, Wolfson M. Electronic cigarette use by college students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:214–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean ME, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Kong G. E-cigarette use among high school and middle school students. Nicotine Tob Res. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntu243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riker CA, Lee K, Darville A, Hahn EJ. E-cigarettes: promise or peril? Nurs Clin North Am. 2012;47:159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cahn Z, Siegel M. Electronic cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy for tobacco control: a step forward or a repeat of past mistakes? J Public Health Policy. 2011;32:16–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grana RA, Ling PM. “Smoking revolution”: a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rooke C, Amos A. News media representations of electronic cigarettes: an analysis of newspaper coverage in the UK and Scotland. Tob Control. 2013;0:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Food and Drug Administration; Department of Health and Human Services. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Federal Register. 2014;79, 80.

- 13.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pepper JK, Ribisl KM, Emery SL, Brewer NT. Reasons for starting and stopping electronic cigarette use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:10345–10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Etter JF, Bullen C. Electronic cigarette: users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction. 2011;106:2017–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Pauly JL, Koh HK, Connolly GN. New cigarette brands with flavors that appeal to youth: tobacco marketing strategies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:1601–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vardavas CI, Anagnostopoulos N, Kougias M, Evangelopoulou V, Connolly GN, Behrakis PK. Short-term pulmonary effects of using an electronic cigarette: impact on respiratory flow resistance, impedance, and exhaled nitric oxide. Chest. 2012;141:1400–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London, UK: SAGE Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamin CK, Bitton A, Bates DW. E-cigarettes: a rapidly growing Internet phenomenon. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:607–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noel JK, Rees VW, Connolly GN. Electronic cigarettes: a new ‘tobacco’ industry? Tob Control. 2011;20:80–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regan AK, Promoff G, Dube SR, Arrazola R. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: adult use and awareness of the ‘e-cigarette’ in the USA. Tob Control. 2013;22:19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popova L, Ling PM. Perceptions of relative risk of snus and cigarettes among US smokers. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:923–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biener L, Hargraves HL. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use in a population-based sample of adult smokers: association with smoking cessation and motivation to quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cobb NK, Abrams DB. E-cigarette or drug-delivery device? Regulating novel nicotine products. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:193–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuschner WG, Reddy S, Mehrotra N, Paintal HS. Electronic cigarettes and thirdhand tobacco smoke: two emerging health care challenges for the primary care provider. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:115–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]