Adolescent Risk Behaviors and Use of Electronic Vapor Products and Cigarettes (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2024 Mar 25.

Published in final edited form as: Pediatrics. 2017 Feb;139(2):e20162921. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2921

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Adolescent use of tobacco in any form is unsafe; yet, use of electronic cigarettes and other electronic vapor products (EVPs) has increased in recent years among this age group. We assessed the prevalence and frequency of cigarette smoking and EVP use among high school students, and associations between health-risk behaviors and both cigarette smoking and EVP use.

METHODS:

We used 2015 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey data (N=15,624) to classify students into four mutually exclusive categories of smoking and EVP use — non-use, cigarette smoking only, EVP use only, and dual use — based on past 30-day use. Prevalence of cigarette smoking and EVP use were assessed overall and by student demographics and frequency of use. Prevalence ratios were calculated to identify associations with health risk-behaviors.

RESULTS:

In 2015, 73.5% of high school students did not smoke cigarettes or use EVPs, 3.2% smoked cigarettes only, 15.8% used EVPs only, and 7.5% were dual users. Frequency of cigarette smoking and EVP use was greater among dual users than cigarette only smokers and EVP only users. Cigarette only smokers, EVP only users, and dual users were more likely than non-users to engage in several injury and violence and substance use behaviors, have ≥4 lifetime sexual partners, be currently sexually active, and drink soda ≥3 times/day. Only dual users were more likely than non-users to not use a condom at last sexual intercourse.

CONCLUSIONS:

EVP use, alone and concurrent with cigarette smoking, is associated with health-risk behaviors among high school students.

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the United States (U.S.).1,2,3 Each year in the U.S., an estimated 480,000 individuals die from smoking, and more than 3,200 adolescents smoke their first cigarette each day.2 In the U.S., data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey indicates that cigarette smoking decreased among high school students during 2011–2015.4 Similarly, data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) has shown that cigarette smoking among this group is at an all-time low since 1991.5 However, this success is tempered by the finding that use of certain emerging tobacco products, including electronic vapor products (EVPs), has increased.4 This has resulted in no change in overall tobacco use among middle and high school students.4

EVPs, also known as electronic nicotine delivery systems,6 include electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), electronic cigars, electronic pipes, vape pipes or pens, and electronic hookahs or hookah pens. EVPs are handheld devices that provide an aerosol that typically includes nicotine, additives, and other harmful and potentially harmful substances that are inhaled by the user.6–8 Data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey indicate that the percentage of U.S. high school students who reported using an e-cigarette in the past 30 days increased from 1.5% to 16.0% during 2011–2015.4

There is a range of potential impacts, including risks and possible benefits, of EVPs on patterns of use of cigarettes and other combustible tobacco products among adults.2 However, among youth, any form of tobacco use, including EVPs, is unsafe.2 EVPs typically contain nicotine; nicotine exposure during adolescence can cause addiction, might harm brain development, and could lead to sustained tobacco product use.2,9,10 Further, longitudinal studies suggest that youth who use EVPs are more likely to subsequently initiate cigarette smoking.11–13 The use of multiple tobacco products among adolescents, including EVPs, is also of concern because multiple tobacco product users have greater nicotine dependence than single-product users.14,15 Accordingly, preventing adolescents from initiating the use of any form of tobacco product, including EVPs, is important to tobacco use prevention and control strategies.16

Given that EVPs are relatively new to the U.S. marketplace, little is known about the use of these products in the context of other health behaviors, which can persist throughout life and contribute to significant morbidity and mortality during adolescence and adulthood.5 Prior research on adolescent tobacco use indicates that cigarette smoking is associated with behaviors related to injury and violence, alcohol and drug use, sexual risk behaviors, physical activity, and school problems (i.e., truancy).17–24 Additionally, research suggests that cigarette smoking may be a marker for these and other problem behaviors.23,25 However, the tobacco product landscape continues to diversify, and EVPs are now the most commonly used tobacco products among U.S. high school students, surpassing conventional cigarettes in 2014.26 To date, studies on the association between EVPs and health-risk behaviors among adolescents and young adults has been limited to examining the associations between e-cigarette and substance use. These studies have found that use of e-cigarettes was associated with alcohol use, binge drinking, and marijuana use.12,27–31

Several studies have assessed the prevalence and reasons for e-cigarette use; however, none have examined associated health-risk behaviors.13,32,33 To address this gap in the literature, this study examined the association between EVPs and a broad range of health-risk behaviors among high school students using data from the national YRBS. This study also compares the frequency of EVP and cigarette use among exclusive and dual users. Given the considerable increases in EVP use and dual tobacco use among adolescents in recent years, the findings from this study could provide critical information to guide public health promotion efforts.

METHODS

Study Sample

The national YRBS monitors six priority health-risk behaviors biennially among high school students.5 The survey uses a three-stage cluster sample design to obtain a nationally representative sample of public and private school students in grades 9 through 12 in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Student participation is anonymous and voluntary, and local parental permission procedures are used. The survey is self-administered and students record their responses directly on a computer-scannable questionnaire or answer sheet. Sampling weights are applied to each record to adjust for nonresponse and the oversampling of black and Hispanic students. Additional details regarding YRBS sampling and psychometric properties have been published elsewhere.34,35 In 2015, the YRBS school response rate was 69%, the student response rate was 86%, the overall response rate was 60%, and the sample size was 15,624. The demographic distribution of the 2015 YRBS sample has been published elsewhere.5 An institutional review board at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention approved the national YRBS.

Measures

Cigarette Smoking and Electronic Vapor Product Use

Current cigarette smoking and EVP use were assessed with the following two questions: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?” and “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use an electronic vapor product?” An introduction to the EVP question was provided to give examples of EVP brands (blu, NJOY, or Starbuzz) and examples of EVPs types (e-cigarettes, e-cigars, e-pipes, vape pipes, vaping pens, e-hookahs, and hookah pens). Response options for both questions were: 0 days, 1 to 2 days, 3 to 5 days, 6 to 9 days, 10 to 19 days, 20 to 29 days, and all 30 days. These questions were examined in two ways. First, each question was used in its original form to examine the number of days students smoked cigarettes and used EVPs (i.e., frequency of use). Second, they were combined to create a four-level variable with mutually exclusive categories: non-use, cigarette smoking only, EVP use only, and dual use (cigarettes and EVP).

Health-Risk Behaviors

Dependent variables included those related to unintentional injuries and violence, substance use, and sexual risk behaviors (Table 1). Variables in these behavioral domains were included in a previous YRBS analysis that examined associations between tobacco use and health-risk behaviors.21 The current study also assessed dietary behaviors and physical activity (Table 1). The cutpoints used for fruit and vegetable consumption were based on earlier fruit and vegetable recommendations that used times/day as the measurement unit,36 because current fruit and vegetable intake recommendations are reported in cup equivalents/day,37 which cannot be calculated using YRBS data. The soda cutpoint was based on a study of Americans aged 2 years of age and older which found that the estimated 90th percentile of daily energy intake from sugar-sweetened beverages was 450 kcal (equivalent to three 12-oz cans of soda).38 The physical activity cutpoint was based on national recommendations.39

Table 1.

Question Wording and Analytic Coding for Included Health Risk Behaviors, National YRBS, 2015

| Health Risk Behavior | Questionnaire Item | Analytic Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Injury and Violence | ||

| Text/email while driving | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you text or e-mail while driving a car or other vehicle? [excludes students who did not drive a car or other vehicle during the past 30 days] | ≥1 vs. 0 days |

| Engaged in a physical fight | During the past 12 months, how many times were you in a physical fight? | ≥1 vs. 0 times |

| Carried a weapon | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you carry a weapon such as a gun, knife, or club? | ≥1 vs. 0 days |

| Attempted suicide | During the past 12 months, how many times did you actually attempt suicide? | ≥1 vs. 0 times |

| Substance Use | ||

| Current alcohol use | During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol? | ≥1 vs. 0 days |

| Current marijuana use | During the past 30 days, how many times did you use marijuana? | ≥1 vs. 0 times |

| Ever synthetic marijuana use | During your life, how many times have you used synthetic marijuana (also called K2, Spice, fake weed, King Kong, Yucatan Fire, Skunk, or Moon Rocks)? | ≥1 vs. 0 times |

| Ever use of other illicit drugs | Combines all of the following individual questionnaire items:During your life, how many times have you used any form of cocaine, including powder, crack, or freebase?During your life, how many times have you sniffed glue, breathed the contents of aerosol spray cans, or inhaled any paints or sprays to get high?During your life, how many times have you used heroin (also called smack, junk, or China White)?During your life, how many times have you used methamphetamines (also called speed, crystal, crank or ice)?During your life, how many times have you used ecstasy (also called MDMA)?During your life, how many times have you used hallucinogenic drugs, such as LSD, acid, PCP, angel dust, mescaline, or mushrooms? | ≥1 vs. 0 times |

| Ever non-medical use of prescription drugs | During your life, how many times have you taken a prescription drug (such as OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin, codeine, Adderall, Ritalin, or Xanax) without a doctor’s prescription? | ≥1 vs. 0 times |

| Sexual Risk Behaviors | ||

| Lifetime sexual partners | During your life, with how many people have you had sexual intercourse? | ≥4 vs. <4 persons |

| Currently sexually active | During the past 3 months, with how many people did you have sexual intercourse? | ≥1 vs. 0 persons |

| Condom use at last sexual intercourse | The last time you had sexual intercourse, did you or your partner use a condom? [excludes students who were not currently sexually active] | No vs. yes |

| Dietary Behaviors and Physical Activity | ||

| Fruit intake | Combines two questionnaire items:During the past 7 days, how many times did you eat fruit? (Do not count fruit juice).During the past 7 days, how many times did you drink 100% fruit juices such as orange juice, apple juice, or grape juice? (Do not count punch, Kool-Aid, sports drinks, or other fruit-flavored drinks.) | <2 times/day vs. ≥2 times/day |

| Vegetable intake | Combines four questionnaire items:During the past 7 days, how many times did you eat green salad?During the past 7 days, how many times did you eat potatoes? (Do not count French fries, fried potatoes, or potato chips.)During the past 7 days, how many times did you eat carrots?During the past 7 days, how many times did you eat other vegetables? (Do not count green salad, potatoes, or carrots.) | <3 times/day vs. ≥3 times/day |

| Soda intake | During the past 7 days, how many times did you drink a can, bottle, or glass of a sports drink such as Gatorade or PowerAde? (Do not count low-calorie sports drinks such as Propel or G2.) | ≥3 times/day vs. <3 times/day |

| Physical activity | During the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day? (Add up all the time you spent in any kind of physical activity that increased your heart rate and made you breathe hard some of the time.) | <7 days vs. 7 days |

Covariates

Three demographic characteristics were included in this analysis: sex (male, female), grade (9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th), and race/ethnicity. Students were classified into four racial/ethnic categories: white non-Hispanic; black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic or Latino (of any race); and other or multiple race. The numbers of students in the other or multiple racial/ethnic group were too small for meaningful analysis. The YRBS questionnaire includes questions about two other types of tobacco use. Students were also asked their current (past 30-day) use of (1) smokeless tobacco products (chewing tobacco, snuff, or dip) as well as (2) cigars, cigarillos, or little cigars. The response options for these questions were split into two groups: any use and no use.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted on weighted data using SUDAAN (Research Triangle Park, NC), a software package that accounts for the survey’s complex sampling design. The percentage of students in each category of the four-level combined cigarette and EVP variable was calculated among students overall and by sex, race/ethnicity, and grade. Chi-square tests were conducted to assess differences by demographics. Among cigarette users, the frequency of cigarette use was compared between cigarette only smokers and dual users using pairwise comparisons (t-statistic). In parallel, among EVP users, the frequency of EVP use was compared between EVP only and dual users using pairwise comparisons. Additionally, multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, grade, smokeless tobacco use, and cigar smoking were used to estimate adjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between cigarette smoking or EVP use and health-risk behaviors using non-users as the referent group. PRs were considered statistically significant if 95% CIs did not include 1.0. Lastly, linear contrasts were conducted to compare results for all health-risk behaviors by cigarette and EVP group using other referents (EVP only vs. cigarette only, dual use vs. cigarette only, and dual use vs. EVP only). Differences were considered significant if the p-value was <0.05.

RESULTS

Prevalence of Use

Nationwide, 75.3% of high school students did not smoke cigarettes or use EVPs, 3.2% smoked cigarettes only, 15.8% used EVPs only, and 7.5% were dual users of both cigarettes and EVPs (Table 2). The distribution across the four-level cigarette and EVP use variable differed significantly by sex (p=0.04), race/ethnicity (p<0.001), and grade level (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Prevalence (and 95% CI) of Cigarette Use and Electronic Vapor Product Use, National YRBS, 2015

| Demographic | Non-use | Cigarette Only | Electronic Vapor Product Only | Dual Use | Chi-Square (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 73.5 (71.1,75.8) | 3.2 (2.6,3.9) | 15.8 (14.2,17.5) | 7.5 (6.5,8.8) | |

| Sex | 3.1 (p=0.04) | ||||

| Female | 75.0 (72.3,77.5) | 2.9 (2.2,3.9) | 15.4 (13.8,17.1) | 6.7 (5.6,8.1) | |

| Male | 72.0 (69.0,74.8) | 3.5 (2.8,4.4) | 16.3 (14.1,18.7) | 8.3 (7.1,9.6) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 5.5 (p< 0.001) | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 71.9 (68.2,75.4) | 3.6 (2.7,4.6) | 15.6 (13.7,17.7) | 8.9 (7.1,11.1) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 80.4 (76.1,84.1) | 2.9 (1.7,4.9) | 13.6 (11.0,16.7) | 3.1 (2.1,4.5) | |

| Hispanic | 71.6 (68.9,74.2) | 2.8 (2.1,3.6) | 19.2 (17.0,21.6) | 6.4 (5.4,7.6) | |

| Grade | 14.8 (p< 0.001) | ||||

| 9 | 79.1 (76.5,81.5) | 1.8 (1.2,2.7) | 13.4 (11.2,15.9) | 5.7 (4.2,7.7) | |

| 10 | 75.2 (71.6,78.4) | 2.3 (1.7, 3.1) | 16.1 (13.9,18.5) | 6.4 (5.0,8.2) | |

| 11 | 70.5 (67.2,73.5) | 4.4 (3.4,5.7) | 16.6 (14.1,19.5) | 8.5 (6.9,10.3) | |

| 12 | 68.4 (64.6,71.9) | 4.4 (3.3,6.0) | 17.6 (15.1,20.4) | 9.6 (7.8,11.7) |

Frequency of Use

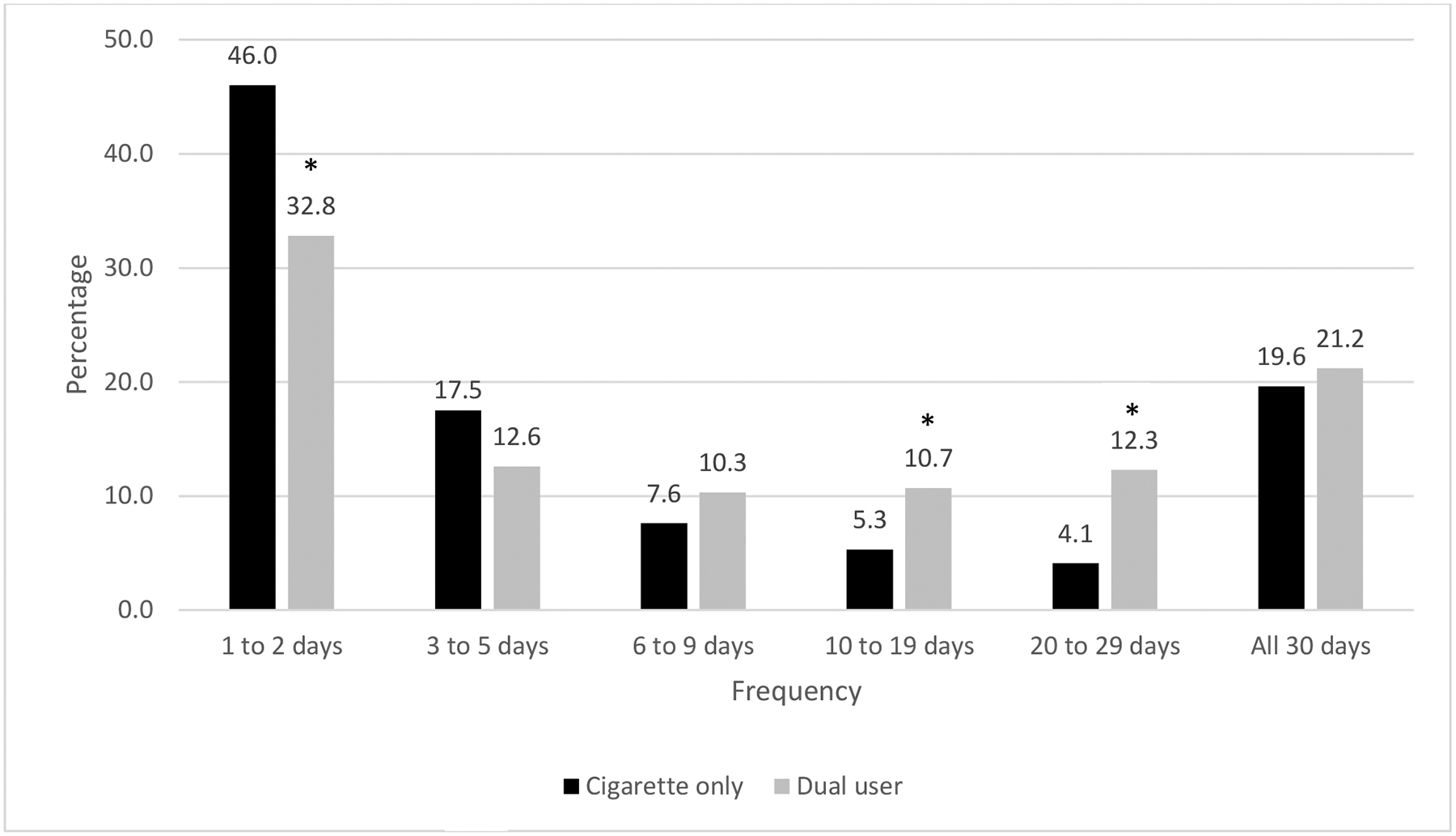

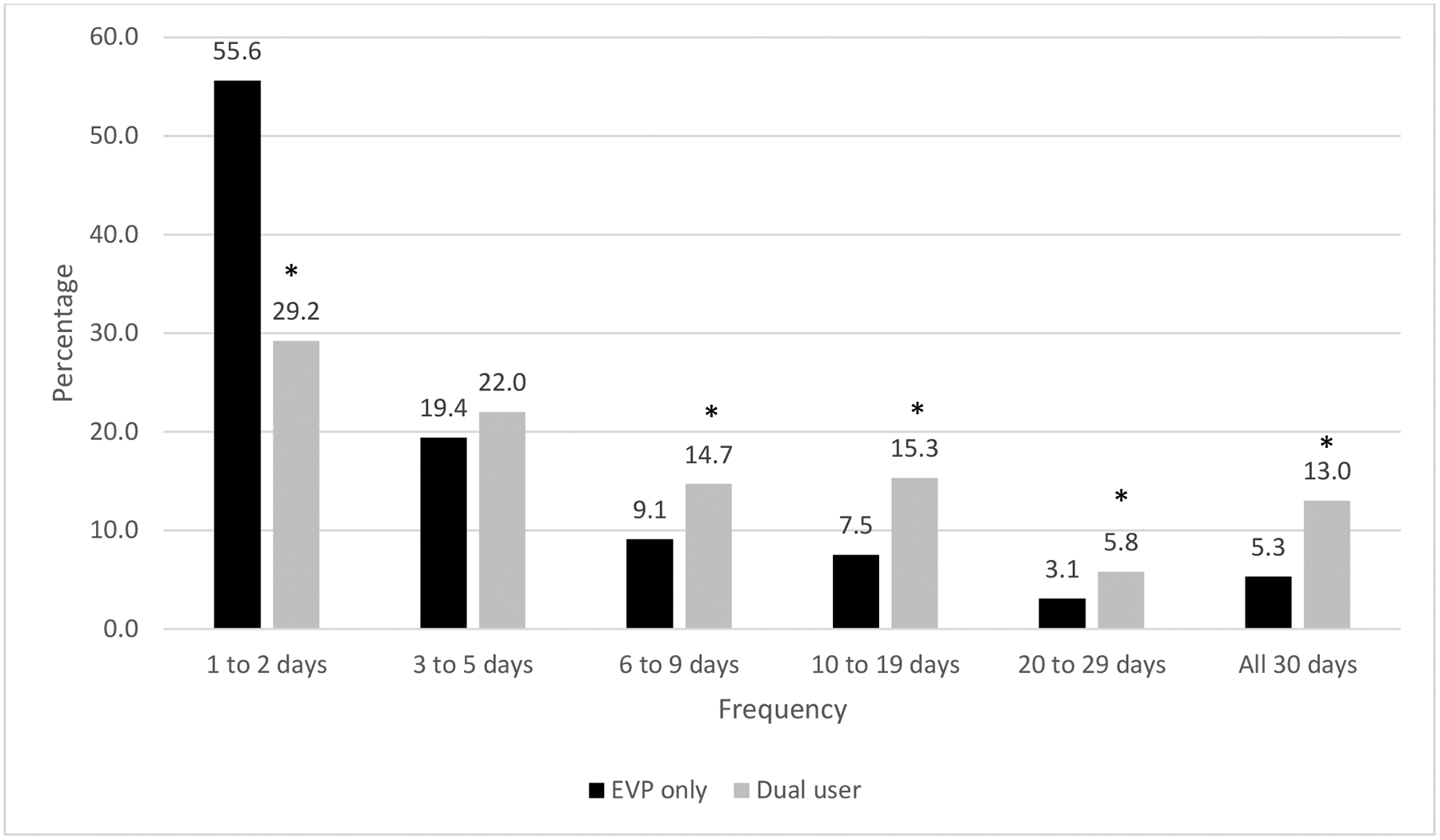

Dual users of cigarettes and EVPs were significantly less likely than cigarette only smokers to smoke cigarettes 1 to 2 days (32.8% vs. 46.0%), but significantly more likely to smoke cigarettes 10 to 19 days (10.7% vs. 5.3%) and 20 to 29 days (12.3% vs. 4.1%) (Figure 1). Dual users of cigarettes and EVPs were significantly less likely than EVP only users to use EVPs 1 to 2 days (29.2% vs. 55.6%), but significantly more likely to use EVPs 6 to 9 days (14.7% vs. 9.1%), 10 to 19 days (15.3% vs. 7.5%), 20 to 29 days (5.8% vs. 3.1%), and all 30 days (13.0% vs. 5.3%) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1. Cigarette smoking frequency among cigarette only smokers and dual users,a National YRBS, 2015b.

a Dual user is defined as a student who currently smokes cigarettes and uses electronic vapor products.

b Statistical difference between cigarette only smokers and dual users is designated with an asterisk (*).

FIGURE 2.

EVP use frequency among EVP-only users and dual users, National YRBS, 2015. “Dual user” is defined as a student who currently smokes cigarettes and uses electronic vapor products. *Statistical difference between EVP-only users and dual users.

Cigarettes, EVP, and Health-Risk Behaviors

Unintentional injuries and violence.

Cigarette only smokers, EVP only users, and dual users were significantly more likely than non-users engage in a physical fight (PR range: 1.72 to 2.87) and attempt suicide (PR range: 1.86 to 4.01) (Table 3). Both EVP only users and dual users were significantly more likely than non-users to text or email while driving (PR: 1.39 and 1.41, respectively). Only dual users were significantly more likely than non-users to carry a weapon (PR: 1.82; 95% CI: 1.30, 2.56).

Table 3.

Risk of Health Risk Behaviors by Cigarette Smoking and EVP Use, National YRBS, 2015

| Health Risk Behavior | Non-use | Cigarette Smoking Only | EVP Use Only | Dual Usea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | PR | % | PR (95% CI) | % | PR (95% CI) | % | PR (95% CI) | |

| Injury and Violence | ||||||||

| Text/email while drivingb | 34.4 | Ref | 53.4 | 1.19 (0.94, 1.49) | 52.7 | 1.39 (1.26, 1.53) | 62.7 | 1.41 (1.21, 1.64) |

| Engaged in a physical fightc | 16.5 | Ref | 36.3 | 1.88 (1.52, 2.33) | 29.6 | 1.72 (1.53, 1.93) | 55.2d,e | 2.87 (2.53, 3.26) |

| Carried a weaponb | 2.5 | Ref | 8.0 | 1.48 (0.84, 2.59) | 4.9 | 1.45 (0.99, 2.12) | 12.0 | 1.82 (1.30, 2.56) |

| Attempted suicidec | 5.7 | Ref | 18.5 | 3.46 (2.51, 4.77) | 10.5f | 1.86 (1.53, 2.25) | 23.3e | 4.01 (3.17, 5.08) |

| Substance Use | ||||||||

| Current alcohol useb | 18.7 | Ref | 72.7 | 2.67 (2.22, 3.20) | 61.9 | 2.62 (2.39, 2.87) | 86.4d,e | 3.29 (2.88, 3.77) |

| Current marijuana useb | 9.9 | Ref | 51.4 | 3.49 (2.80, 4.36) | 43.7 | 3.70 (3.16, 4.32) | 69.7d,e | 5.22 (4.42, 6.18) |

| Ever synthetic marijuana use | 3.2 | Ref | 26.1 | 5.39 (3.84, 7.58) | 14.5f | 3.67 (3.04, 4.44) | 40.2d,e | 8.65 (6.60, 11.35) |

| Ever use of other illicit drugsg | 6.1 | Ref | 29.2 | 3.23 (2.17, 4.83) | 19.8 | 2.73 (2.25, 3.30) | 50.7d,e | 5.75 (4.48, 7.40) |

| Ever non-medical use of prescription drugs | 9.3 | Ref | 36.1 | 2.66 (2.04, 3.48) | 24.8 | 2.30 (1.97, 2.68) | 54.9d,e | 4.13 (3.44, 4.96) |

| Sexual Risk Behaviors | ||||||||

| Four or more lifetime sexual partners | 6.1 | Ref | 33.8 | 3.84 (2.86, 5.16) | 16.9f | 2.35 (1.93, 2.87) | 39.0e | 4.60 (3.64, 5.81) |

| Current sexual activityh | 21.5 | Ref | 56.3 | 1.93 (1.64, 2.28) | 46.2 | 1.86 (1.65, 2.10) | 63.8e | 2.30 (1.91, 2.78) |

| Did not use a condom at last sexual intercoursei | 41.5 | Ref | 48.4 | 1.17 (0.93, 1.49) | 38.1 | 0.93 (0.82, 1.05) | 52.2e | 1.27 (1.07, 1.50) |

| Dietary Behaviors and Physical Activity j | ||||||||

| Fruit <2 times/day | 69.4 | Ref | 71.5 | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) | 65.7 | 0.95 (0.90, 1.01) | 66.8 | 0.99 (0.93, 1.06) |

| Vegetables <3 times/day | 86.6 | Ref | 82.8 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) | 84.5 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 79.0 | 0.94 (0.91, 0.98) |

| Soda ≥3 times/day | 5.3 | Ref | 15.3 | 2.66 (1.79, 3.95) | 7.6f | 1.35 (1.04, 1.76) | 18.1e | 3.03 (2.26, 4.05) |

| <7 days of physical activity | 74.1 | Ref | 76.4 | 1.07 (1.00, 1.15) | 66.7f | 0.91 (0.88, 0.95) | 69.5e | 1.01 (0.96, 1.07) |

Substance use behaviors.

Cigarette only smokers, EVP only users, and dual users were significantly more likely than non-users to currently drink alcohol (PR range: 2.62 to 3.29), currently use marijuana (PR range: 3.49 to 5.22), ever use synthetic marijuana (PR range: 3.67 to 8.65), ever use other illicit drugs (PR range: 2.73 to 5.75), and report ever non-medical use of prescription drugs (PR range: 2.30 to 4.13) (Table 3).

Sexual risk behaviors.

Cigarette only smokers, EVP only users, and dual users were significantly more likely than non-users to have ≥4 lifetime partners (PR range: 2.35 to 4.60) and be currently sexually active (PR range: 1.86 to 2.30) (Table 3). Only dual users were significantly more likely than non-users to not use a condom at last sexual intercourse (PR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.50).

Dietary behaviors and physical activity.

Dual users were significantly less likely to eat vegetables <3 times/day when compared to non-users (PR: 0.94; 95% CI: 0.91, 0.98) (Table 3). Cigarette only smokers, EVP only users, and dual users were significantly more likely than non-users to drink soda ≥3 times/day (PR range: 1.35 to 3.03). EVP only users were significantly less likely to not engage in daily physical activity when compared to non-users (PR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.88, 0.95).

Linear contrasts.

Engaging in health-risk behaviors did not generally differ between EVP only users and cigarette only smokers (Table 3); however, cigarette only smokers were significantly more likely than EVP only users to attempt suicide, ever use synthetic marijuana, have ≥4 lifetime sexual partners, drink soda ≥3 times/day, and be physically active <7 days in the 7 days before the survey. When comparing dual users to cigarette only smokers, dual users were significantly more likely than cigarette only smokers to engage in all substance use behaviors and physical fighting. When comparing dual users to EVP only users, significant differences were observed for all substance use and sexual risk behaviors, physical fighting, attempted suicide, soda intake, and physical activity. In all cases, dual users were more likely to engage in these behaviors compared to EVP only users.

Discussion

The findings of this study are consistent with other studies documenting an association between EVP use, particularly e-cigarettes, and other substance use.12,27–31 However, this study also shows that EVP use is associated with other health-risk behaviors. For a majority of the behaviors examined in this study, cigarette only smokers and EVP only users were as likely to engage in that behavior, suggesting that the associations between health-risk behaviors and EVP use mirror the associations between health-risk behaviors and conventional cigarettes. The pattern of cigarette only and EVP only users having intermediate risks between non-users and dual users is consistent with other published studies.28,29 Consequently, addressing the diversity of tobacco use as part of youth health promotion efforts is important.

Research on conventional cigarettes suggests that smoking occurs along with, or clusters, with various health-risk behaviors, and that cigarette smoking may serve as a marker for these behaviors.17–25 This is important to consider in the context of public health practice, as research indicates that, among adults, the odds of reporting fair or poor health status increase with each unhealthy behavior that an individual engages in.40 The development of certain unhealthy behaviors during adolescence puts adolescents on trajectories toward chronic disease.25 The reason for the association between tobacco use and other health-risk behaviors may be due to common factors (i.e., lack of resources such as health education), motivation by similar goals (i.e., rejecting conventional social norms), or the activation of similar neural pathways.24,25,41 Cigarette smoking has also been found to be associated with emotional and behavioral problems which could also make adolescents more vulnerable for developing other health-risk behaviors.42,43 Future studies may show similar vulnerabilities among EVP users, including whether e-cigarette use may be introducing youth with relatively low risk profiles to substance use. Therefore, comprehensive efforts to address the health-risk behaviors among adolescents are warranted, including prevention strategies focused on all forms of tobacco use, including EVPs.

Despite the harms of EVP use among adolescents, use of these products among U.S. middle and high school students has increased considerably in recent years for several possible reasons. First, in 2014, 18 million youth were exposed to e-cigarette advertising.44 Given the link between marketing of conventional tobacco products and tobacco initiation among youth, it is likely that increases in e-cigarette marketing are contributing to increases in EVP use.44 Second, the flavorings frequently used in EVPs are appealing to adolescents.6,8,45 Third, use of EVPs may be considered more socially acceptable, particularly in indoor areas where conventional cigarette smoking is prohibited.6 Fourth, EVPs have been relatively easy for youth to access; they are available in retail stores, mall kiosks, and the Internet.6,46 However, efforts are underway to reduce potential public harms of these products through regulation. In May 2016, FDA finalized a rule extending its authority to all products that meet the definition of a tobacco product, including e-cigarettes. E-cigarettes are considered a tobacco product due to a 2011 court ruling.47 The 2016 rule sets a national minimum age for sales, requires tobacco product ingredient reporting and reporting of harmful and potentially harmful constituents, and ensures FDA premarket review of new and changed tobacco products.48

This study found that dual users smoked cigarettes more frequently than cigarette only smokers and used EVPs more frequently than EVP only users. These findings are consistent with research showing that among U.S. adolescents who ever smoked cigarettes, e-cigarette users were less likely than non-users to abstain from cigarettes.49 Additionally, a study of Polish adolescents found that dual users of electronic and conventional cigarettes were more likely to smoke cigarettes daily and less likely to smoke fewer cigarettes per day than students who exclusively smoked conventional cigarettes.50 This lack of decline in smoking frequency among youth e-cigarette users is contrary to studies showing that EVP use may reduce cigarette smoking frequency among adults.51 These findings underscore the importance of evidence-based measures to prevent use of all forms of tobacco use, including experimental or intermittent use, among youth.52 Studies have shown that symptoms of tobacco dependence are evident even among adolescents who used only a single tobacco product on as few as 1 to 2 days during the previous month.15

In addition to population-based interventions, such as youth access restrictions and comprehensive smoke-free policies that include EVPs,53 actions can also be taken in the clinical setting to address youth tobacco use. Screening of patients and their caregivers for EVP use can be incorporated into tobacco use screening.6 Counseling about the harms associated with adolescent tobacco use, including EVP use, is critical.6 It is particularly important that this counseling identify and correct misperceptions about the use of EVP products in this population.40

This study has at least four limitations. First, YRBS data are self-reported and students may misreport their behaviors. Although the EVP question is new to YRBS, a psychometric study has shown that the YRBS questions generally have good test-retest reliability.34 Second, the data are from an observational study; therefore, causality cannot be determined. Third, some of the behaviors investigated may not be risky for particular individuals under certain circumstances. For example, sexual intercourse without a condom may not be risky for mutually monogamous partners when another contraceptive method is used. Lastly, data are only collected on adolescents who attend school and, therefore, are not representative of all individuals in this age group. However, nationwide in 2012, approximately 3% of persons 16–17 years were not enrolled in a high school program and had not completed high school.54

Conclusions

EVP use, alone and concurrent with cigarette smoking, is associated with health-risk behaviors among high school students. Moreover, dual users of EVPs and conventional cigarettes reported using these products more frequently than exclusive users of these products. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive efforts to address health-risk behaviors among adolescents, including prevention strategies focused on all forms of tobacco use, including EVPs. Additionally, educational and counseling efforts focusing on the harms associated with adolescent tobacco use, including EVPs, are critical.

What’s Known on This Subject.

While cigarette smoking among adolescents has decreased, the use of certain emerging tobacco products, such as electronic vapor products (EVPs), has increased. Risks, including health-risk behaviors, associated with EVP use have not yet been fully explored.

What This Study Adds.

EVP use, alone and concurrent with cigarette smoking, is associated with several health-risk behaviors among high school students. This suggests comprehensive efforts to address health-risk behaviors among adolescents are warranted, including prevention strategies focused on all forms of tobacco use.

Abbreviations:

EVP

electronic vapor product

YRBS

Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps.

References

- 1.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: What it Means to You. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh T, Arrazola RA, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students — United States, 2011–2015. MMWR. 2016;65(14):361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance — United States, 2015. MMWR. 2016;65(No. SS-6):1–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Academy of Pediatrics. Electronic nicotine delivery systems. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):1018–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy M E-cigarettes could addict a new generation of youth to nicotine, doctors are told. BMJ. 2015;351:h5728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauterstein D, Hoshino R, Gordon T, Watkins B-X, Weitzman M, Zelikoff. The changing face of tobacco use among United States youth. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2014;7(1):29–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: Nicotine Addiction. A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Health Promotion and Education, Office on Smoking and Health; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10.England LJ, Bunnell RE, Pechacek TF, Tong VT, McAfee TA. Nicotine and the Developing Human: A Neglected Element in the Electronic Cigarette Debate. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2):286–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA. 2015;314(7):700–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unger JB, Soto DW, Leventhal A. E-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette and marijuana use among Hispanic young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163:261–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Berhane K, et al. E-cigarettes and future cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20160379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanza ST, Vasilenko SA. New methods shed light on age of onset as a risk factor for nicotine dependence. Addict Behav. 2015;50:161–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apelberg BJ, Corey CG, Hoffman AC, et al. Symptoms of tobacco dependence among middle and high school tobacco users: results from the 2012 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(Suppl 1):S4–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC Office on Smoking and Health. E-cigarette information. http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/pdfs/cdc-osh-information-on-e-cigarettes-november-2015.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2016.

- 17.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Grucza RA, Bierut LJ. Youth tobacco use type and associations with substance use disorders. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1371–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn MS. Association between physical activity and substance use behaviors among high school students participating in the 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Psychol Rep. 2014;114(3):675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gart R, Kelly S. How illegal drug use, alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms affect adolescent suicidal ideation: A secondary analysis of the 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2015;36(8):614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Everett SA, Giovino GA, Warren CW, Crossett L, Kann L. Other substance use among high school students who use tobacco. J Adol Health. 1998;23(5):289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Everett SA, Malarcher AM, Sharp DJ, Husten CG, Giovino GA. Relationship between cigarette, smokeless tobacco, and cigar use, and other health risk behaviors among US high school students. J Sch Health. 2000;70(6):234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Escobedo LG, Reddy M, DuRant RH. Relationship between cigarette smoking and health risk and problem behaviors among US adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin G, McCarthy W, Slade S, Bailet W. Links between smoking and substance use, violence, and social problems. CHKS Factsheet #5. Los Alamitos, CA: WestEd; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pesa JA. The association between smoking and unhealthy behaviors among a national sample of Mexican-American adolescents. J Sch Health. 1998;68(9):376–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spring B, Moller AC, Coons MJ. Multiple health behaviors: overview and implications. J Public Health. 2012;34(S1):i3–i10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Apelberg BJ, Bunnell RE, Choiniere CJ, King BA, Cox S, McAfee T, Caraballo RS. Tobacco use among middle and high school students — United States, 2011–2014. MMWR. 2015;64(14):381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camenga DR, Kong G, Cavallo DA, et al. Alternate tobacco product and drug use among adolescents who use electronic cigarettes, cigarettes only, and never smokers. J Adol Health. 2014;55:588–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kristjansson AL, Mann MJ, Sigfusdottir ID. Licit and illicit substance use by adolescent e-cigarette users compared with conventional cigarette smokers, dual users, and nonusers. J Adol Health. 2015;57(5):562–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wills TA, Knight R, Williams RJ, Pagano I, Sargent JD. Risk factors for exclusive e-cigarette use and dual e-cigarette use and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e43–e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Surís J, Berchtold A, Akre C. Reasons to use e-cigarettes and associations with other substances among adolescents in Switzerland. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;153:140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saddleson ML, Kozlowski LT, Giovino GA, Hawk LW, Murphy JM, McLean MG, Goniewicz, Homish GG, Wrotniak BH, Mahoney MC. Risky behaviors, e-cigarette use and susceptibility of use among college students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;149:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bold KW, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Reasons for trying e-cigarettes and risk of continued use. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20160895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamboj A, Spiller HA, Casavant MJ, Chounthirath T, Smith GA. Pediatric exposure to e-cigarettes, nicotine, and tobacco products in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137(6):e20160041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, Kinchen SA, Sundberg EC, Ross JG. Reliability of the 1999 Youth Risk Behavior Survey questionnaire. J Adol Health. 2002;31(4):336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. MMWR 2013;62(RR-01):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015 – 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogden CL, Kit BK, Carroll MD, Park S. Consumption of sugar drinks in the United States, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;71:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 40.United Health Foundation. America’s Health Rankings® Spotlight: Impact of Unhealthy Behaviors. Minnetonka, MN: United Health Foundation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turbin MS, Jessor R, Costa FM. Adolescent cigarette smoking: health-related behavior or normative transgression. Prev Sci. 2000;1(3):115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vega WA, Chen KW, Williams J. Smoking, drugs, and other behavioral health problems among multiethnic adolescents in the NHSDA. Addictive Behav. 2007;32:1949–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giannakopoulos G, Tzavara C, Dimitrakaki C, Kolaitis G, Rotsika V, Tountas Y. Emotional, behavioral problems and cigarette smoking in adolescence: findings of a Greek cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-cigarette ads and youth. http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/ecigarette-ads/index.html. Accessed April 15, 2016. [PubMed]

- 45.Hildick-Smith GJ, Pesko MF, Shearer L, et al. A practitioner’s guide to electronic cigarettes in the adolescent population. J Adol Health. 2015;57(6):574–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose SW, Barker DC, D’Angelo H, et al. The availability of electronic cigarettes in US retail outlets, 2012: results of two national studies. Tob Control. 2014;23:iii10–ii16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sottera, Inc. v. Food & Drug Administration. Available at: http://www.wlf.org/Upload/litigation/briefs/SmokingEverywherevFDA-WLFAmicus.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2016.

- 48.Food and Drug Administration. Deeming Tobacco Products To Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Regulations on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products; Final Rule. 81 Federal Register; (10 May 2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dutra LM, Glantz SA. Electronic cigarettes and conventional cigarette use among US adolescents. A cross-sectional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(7):610–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goniewicz ML, Leigh NJ, Gawron M, Nadolsja J, Balwicki L, McGuire C, Sobczak A. Dual use of electronic and tobacco cigarettes among adolescents: a cross-sectional study in Poland. Int J Public Health. 2016;61(2):189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adkison SE O’Connor RJ Bansal-Travers M, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: international tobacco control four-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(3):207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53.CDC Office on Smoking and Health. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: Key facts. 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/stateandcommunity/pdfs/ends-key-facts2015.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2016.

- 54.Stark P, Noel AM. Trends in High School Dropout and Completion Rates in the United States: 1972–2012. Publication No. NCES 2015–015. Washington, DC: US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]