Deep Vein Thrombosis of the Upper Extremity: A Systematic Review (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) arises with an incidence of about 1 per 1000 persons per year; 4–10% of all DVTs are located in an upper extremity (DVT-UE). DVT-UE can lead to complications such as post-thrombotic syndrome and pulmonary embolism and carries a high mortality.

Method

This review is based on pertinent literature, published from January 1980 to May 2016, that was retrieved by a systematic search, employing the PRISMA criteria, carried out in four databases: PubMed (n = 749), EMBASE (n = 789), SciSearch (n = 0), and the Cochrane Library (n = 12). Guidelines were included in the search.

Results

DVT-UE arises mainly in patients with severe underlying diseases, especially cancer (odds ratio [OR] 18.1; 95% confidence interval [9.4; 35.1]). The insertion of venous catheters—particularly central venous catheters—also elevates the risk of DVT-UE. Its clinical manifestations are nonspecific. Diagnostic algorithms are of little use, but ultrasonography is very helpful in diagnosis. DVT-UE is treated by anticoagulation, with heparin at first and then with oral anticoagulants. Direct oral anticoagulants are now being increasingly used. The thrombus is often not totally eradicated. Anticoagulation is generally continued as maintenance treatment for 3–6 months. Interventional techniques can be used for special indications. Patients with DVT-UE have a high mortality, though they often die of their underlying diseases rather than of the DVT-UE or its complications.

Conclusion

DVT of the upper extremity is becoming increasingly common, though still much less common than DVT of the lower extremity. The treatment of choice is anticoagulation, which is given analogously to that given for DVT of the lower extremity.

Deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity (DVT-UE) can occur in any of the veins of the upper extremity or thoracic inlet. These include the jugular, brachiocephalic, subclavian, and axillary veins as well as the more distal brachial, ulnar, and radial veins. DVT-UE must be distinguished from thrombosis of the superficial veins, i.e., the cephalic and basilic veins (1).

Idiopathic DVT-UE and cases due to anatomical variants are known as primary DVT-UE. The occurrence of secondary DVT-UE, on the other hand, is associated with tumor disease, intravenous catheters, and pacemaker cables (2). The growing incidence of these risk factors and therefore of the resulting cases of DVT-UE is leading to increasing interest in this disease.

The data on DVT-UE are limited and heterogeneous. No randomized controlled trials have been published, and there are very few nonrandomized interventional or comparative studies. Most of the publications on DVT-UE are case series or cohort studies. This precludes a formal meta-analysis but permits a systematic review.

Methods

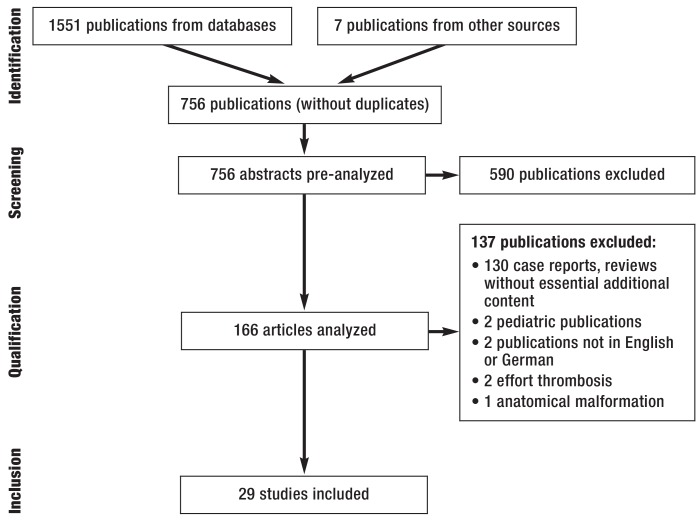

We conducted a structured analysis of the relevant publications listed in the databases PubMed (n = 749), EMBASE (n = 789), SciSearch (n = 0), and the Cochrane Library (n = 12) and published between January 1980 and May 2016. Following identification and removal of duplicates, the data were analyzed in accordance with the principles of the PRISMA statement (efigure). The methods are described in detail in eBox 1 (3). This search strategy identified a total of 756 publications, of which 29 were classed as relevant.

eFigure.

PRISMA diagram (PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses)

Results

Etiology, epidemiology, and risk factors

The annual incidence of DVT is approximately 1/1000, and the proportion of DVT-UE is around 4 to 10% (4, 5). This means that somewhere between 3200 and 8000 people in Germany are affected. Secondary DVT-UE is much more common than primary DVT-UE, making up around 80% of cases (6). The causes of primary DVT-UE and the options for treatment are presented in eBox 2.

eBOX 2. Primary deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity (2).

- Occurrence:

Spontaneous or associated with anatomical anomalies: shoulder girdle syndrome, Paget–von Schroetter syndrome (PSS; venous thrombosis of the subclavian vein in thoracic inlet syndrome), cervical rib, exostoses, clavicular fractures, hypertrophy of the scalenus muscle (2, e11). - Special forms:

Effort thrombosis in the presence of stress; paraneoplastic thrombosis caused by compression due to Pancoast tumor. - Diagnosis:

Sonography, computed tomography (2) - Treatment:

- Whenever feasible, surgical elimination of the cause: removal of the obstruction to blood flow (e.g., anterior scalenotomy or resection of a cervical rib) combined with catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT)

- As initial treatment, anticoagulation alone is inferior to surgical and/or interventional procedures.

- Stent angioplasty has largely been abandoned (2, 20, e12, e13).

The incidence of DVT-UE is on the rise. The presumed reason for this development is the increased insertion of central venous catheters (CVC), peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC), and cardiac pacemakers (2, 6– 8).

Other factors considered to increase the risk of DVT-UE are age >40 years, immobilization, and a history of thromboembolic events (etable 1) (2, 6, 9).

eTable 1. Characteristics of patients with deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity.

| Authors | Year | Pat. (n) | Age (y)*1 | M (%) | DVT history (%) | Hospitalized*2 | Op. (%) | CVC (%) | Tumor (%)*3 | Jadad score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleker et al. (1) | 2016 | 102 | 54 | 43 | 5 | – | 12 | 43 | 41 | 1 |

| Stone et al. (9) | 2016 | 229 | 50 | 34 | 28 | 47 | 20 | 78 | 31 (14) | 1 |

| Schleyer et al. (e14) | 2014 | 50 | 49 | 70 | – | 92 | 46 | 44 | 31 | 1 |

| Lee et al. (8) | 2012 | 373 | 51 | 44 | – | 78 | 27 | 93 | 49 | 1 |

| Spencer et al. (11) | 2007 | 69 | 65 | 52 | 7 | – | 49 | 62 | 44 (26) | 1 |

The formation of a DVT-UE seems to be particularly favored by the combination of irritation of the vessel wall by a CVC or by chemotherapeutics and tumor-related hypercoagulability of the blood (10).

Foreign bodies in the vascular system represent the most important independent risk factor for DVT-UE. More than half of the patients with DVT-UE have a CVC or a cardiac pacemaker in the affected area of the circulation (11, 12). The presence of a CVC increases the risk of DVT-UE sevenfold (odds ratio [OR] 7.3, 95% confidence interval [5.79, 9.21]; p<0.0001) (12). The degree of risk depends on the diameter, type, and position of the catheter and is also increased by the presence of infection (13, 14). Evans et al., for example, demonstrated that triple-lumen PICC increase the ratio by a factor of 20 compared with single-lumen PICC (OR 19.5, [3.45, >100]; p<0.01) (15). The findings for cardiac pacemakers are comparable: DVT-UE was demonstrated in over 60% of pacemaker patients at 6-month follow-up (16).

The second independent risk factor for DVT-UE is malignant disease. Up to 49% of patients with DVT-UE have a tumor (8), and underlying malignant disease increases the risk by a factor of 18 (OR 18.1, [9.4, 35.1]) compared with patients who do not have a malignancy (2, 17).

Surgical intervention is the third principal risk factor for DVT-UE. Lee et al. showed that 27% of patients with DVT-UE had a history of surgery (8). According to Mino et al., as many as 53.8% of patients developed DVT-UE postoperatively, while DVT of the lower extremity (DVT-LE) occurred in 35.9% of cases. The relevance of these DVT-UE—diagnosed in the course of screening—is unclear (18).

The vessels most often affected by DVT are the subclavian vein (62%), the axillary vein (45%), and the jugular vein (45%), with more than one thrombosis demonstrated in some instances (etable 2) (8).

eTable 2. Sites of deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremities.

| Authors | Year | Patients(n) | Patients(%) | Internal jugular vein(%) | Axillary vein(%) | Brachial vein(%) | Subclavian vein(%) | Radial vein(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schleyer et al. (e14) | 2014 | 50 | – | 38 | 21 | 25 | 16 | – |

| Lee et al. (8) | 2012 | 373 | > 1 vein*: 62 | 45 | 45 | 29 | 62 | 1 |

| 1 vein*: 38 | 11 | 2 | 7 | 13 | 1 | |||

| Mino et al. (18) | 2014 | 21 | – | 57 | – | – | 43 | – |

| Kovacs et al. (e15) | 2007 | 74 | – | 1 | 34 | 42 | 22 | – |

DVT of the upper extremity differs in a number of ways from DVT of the lower extremity, as shown in eBox 3.

eBOX 3. Comparison of deep vein thrombosis of the upper and lower extremities (11, 12).

- Distribution:

- Deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity (DVT-UE): 11–14%.

- Deep vein thrombosis of the lower extremity (DVT-LE): 86–89%.

- Risk factors (12):

- DVT-LE: Age (odds ratio [OR] 2.35; 95% confidence interval [1.68, 3.29]; p<0.0001), high body mass index (OR 1.7; [1.25; 2.31]; p = 0.0007), pregnancy, surgical intervention

- DVT-UE: Smoking (OR 1.26; [0.87, 1.84]; p = 0.23), malignancy, foreign body in vascular system

- Complications (19):

- Pulmonary embolism: risk ca. 5 times higher in DVT-LE (32% versus 6%)

- Post-thrombotic syndrome: risk ca. 10 times higher in DVT-LE (56% versus 5%)

- Recurrence rate with optimal treatment (12 months) 2 to 5 times higher in DVT-LE (10% versus 2–5%)

- Simultaneous occurrence of both DVT-LE and DVT-UE is possible, and it may be advisable to include the other side of the body in the diagnostic work-up (6).

Clinical symptoms

Signs of venous congestion such as swelling, pain, edema, cyanosis, and dilation of the superficial veins are among the typical, but not specific, symptoms of DVT-UE (6, 19, 20). A not inconsiderable proportion of DVT-UE (33 to 60%) are asymptomatic, so many cases may well go undetected (6). Localized neck or shoulder pain may point to a thrombosis in the subclavian or axillary vein. Weakness and paresthesia of the affected arm may occur, as may elevated body temperature, but both of these signs are observed only sporadically (2, 19).

Clinical examination has specificity of only 30 to 64%. The detection rate can be improved by means of algorithms and, particularly, diagnostic imaging procedures (2, 10).

Diagnosis

The currently valid German S2 guideline provides no algorithm for the diagnosis of DVT-UE.

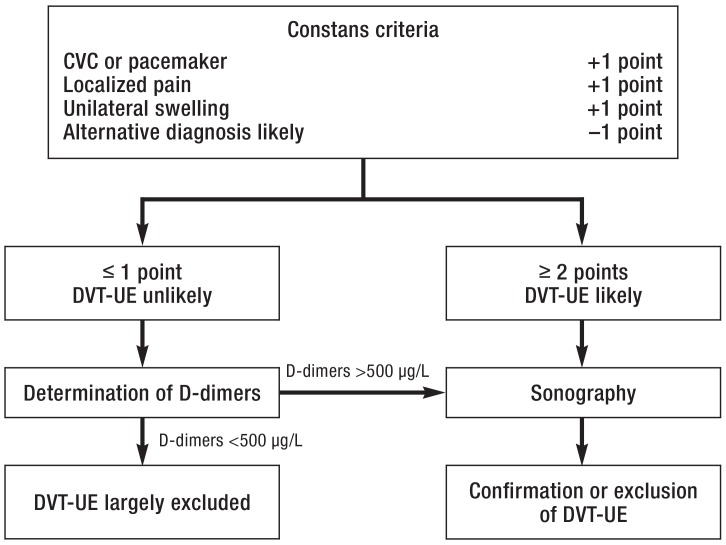

A clinical scoring system to estimate the probability of DVT-UE was published by Constans et al. in 2008, and in 2016 van Es et al. added D-dimers and sonography to create a diagnostic algorithm (figure 1) (21, 22). It remains to be seen how widely this proposal will be taken up.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic algorithm based on the Constans criteria (modified from [22, 23])

CVC, central venous catheter; DVT-UE, deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity

DVT-UE occurs especially in hospitalized patients and is associated with tumor disease and presence of a CVC, which greatly diminishes the usefulness of D-dimers in the diagnostic work-up (19). Although the negative predictive value can be raised by an age-adjusted cut-off level for D-dimers, the D-dimer test alone is of limited value (23).

For patients not being treated in hospital, the combination of a clinical score (the Wells score), D-dimer determination, and compression sonography achieved a negative predictive value of 99.0% [96.3, 99.9] for DVT-LE (24). However, the parameters of the scoring system (e.g., leg circumference) mean that it cannot be used for DVT-UE.

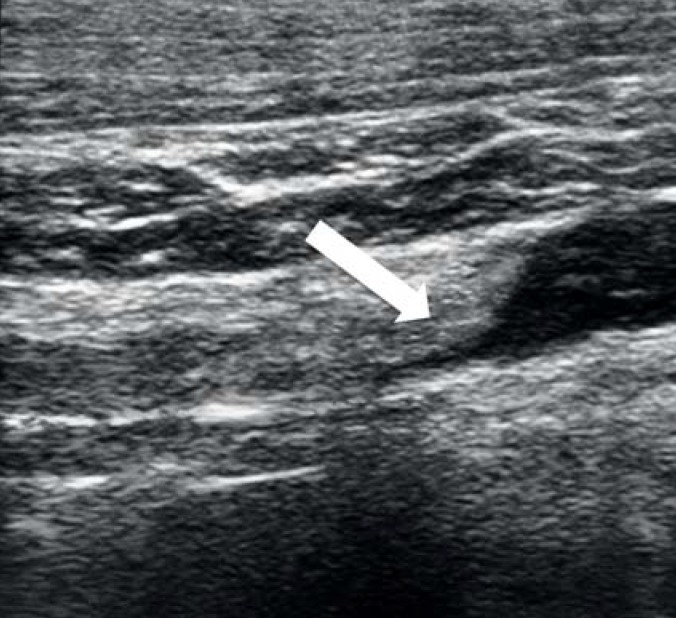

If DVT-UE is suspected, the simplest and swiftest diagnostic modality is sonography (figure 2). Contrast medium enhancement is unnecessary (2, 7, 10). Compression sonography, with 97% sensitivity and 96% specificity, is particularly accurate in detecting DVT-UE in the distal veins (25). For reasons of anatomy, compression sonography is not applicable to the proximal brachiocephalic and subclavian veins, where Doppler or color-coded duplex sonography is used instead (2).

Figure 2.

Sonography of the left subclavian vein

Depiction of a several-day-old thrombus with almost complete obstruction of the lumen (arrow)

Should the findings not be clear, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance phlebography is recommended (26).

Because of its high sensitivity and specificity, contrast-enhanced CT is increasingly being used for diagnosis of DVT-UE. Both arms can be imaged in one examination, together with the venous outflow from arm and head as well as the extension of the thrombus to central (figure 3). Conventional phlebography is also recommended for further investigation of DVT-UE (figure 4), despite the lack of data on sensitivity and specificity, and is used especially in interventional procedures (2).

Figure 3.

Computed tomographic (CT) image of deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity. Verification of the longitudinally extensive thrombus at the junction of the right subclavian vein and the superior vena cava (arrow)

Figure 4.

Phlebography of the brachial vein. The abrupt ending of the contrast medium column demonstrates the presence of a thrombus in the axillary vein with only slight collateralization (arrow)

Treatment

The goals of the primary treatment of DVT-UE by means of anticoagulation measures are to dissolve the thrombus, alleviate the symptoms, and prevent pulmonary embolism and post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS). Secondary preventive treatment must ensure there is no recurrence of DVT (2, 27).

The initial treatment follows the recommendations for DVT-LE: unfractionated (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) are used (26). Drugs and dosages are listed in the Table. LMWH can generally be administered without regularly checking anti-factor-Xa activity (28). If renal insufficiency (glomerular filtration rate = 30 mL/min) is present or the patient is dependent on dialysis, anticoagulation with UFH is advisable. A bolus of 5000 IU heparin is recommended, followed by 15–20 IU/kg body weight (BW) with monitoring of partial thromboplastin time (pTT) (26).

Table. Initial anticoagulation and maintenance treatment for DVT-UE*1.

| Substance*2 | Initial dose | Maintenance dose |

|---|---|---|

| LMWH | ||

| Certoparin | 8000 IU (2/day s. c.) | 8000 IU (2/day s. c.) |

| Dalteparin | 100 IU/kg BW (2/day s. c.) 200 IU/kg BW (1/day s. c.) | 100 IU/kg BW (2/day s. c.) 200 IU/kg BW (1/day s. c.) |

| Enoxaparin | 1.0 mg/kg BW (2/day s. c.) | 1.0 mg/kg BW (2/day s. c.) |

| Tinzaparin | 175 IU/kg BW (1/day s. c.) | 175 IU/kg BW (1/day s. c.) |

| UFH | ||

| Heparin sodium/calcium | Bolus: 5000 IU 15–20 IU/kg BW/h (i. v.) | ca. 15–20 IU/kg BW/h (i. v. _under aPTT monitoring) |

| Pentasaccharide | ||

| Fondaparinux | 7.5 mg (1/day s. c.) <50 kg: 5 mg (1/day s. c.) >100 kg: 10 mg (1/day s. c.) | 7.5 mg (1/day s. c.) <50 kg: 5 mg (1/day s. c.) >100 kg: 10 mg (1/day s. c.) |

| DOAC | ||

| Dabigatran | – | 150 mg (2/day p. o.) |

| Rivaroxaban | 15 mg (2/day. 3 weeks p. o.) | 20 mg (1/day p. o.) |

| Apixaban | 10 mg (2/day. 1 week p. o.) | 5 mg (2/day p. o.) |

| Edoxaban | – | 60 mg (1/day p. o.) |

Regular thrombocyte counts are necessary for early detection of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia type II (HIT II) in treatments lasting more than 5 days. If the patient has a history of HIT II, fondaparinux (FDX) can be used for anticoagulation. Monitoring of treatment success is not necessary, but is possible by means of determination of anti-factor-Xa activity (26).

Moreover, the direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) rivaroxaban and apixaban are licensed for the initial treatment of DVT-LE and can also be used in DVT-UE. The initial treatment phase is 21 days for rivaroxaban and 7 days for apixaban, compared with 5 days for LMWH, UHF, and FDX (26).

Vitamin K antagonists (VKA) have largely been employed for maintenance treatment to date, with an international normalized ratio (INR) target range of 2.0 to 3.0. However, DOAC are increasingly being used for maintenance therapy of DVT (table) (26). Various studies have confirmed the efficacy of DOAC, although they were not specific for DVT-UE (e1– e6). Besides being able to do without regular INR monitoring, DOAC have the advantage of reducing the rate of major hemorrhage (by around 40% versus VKA). Dose adjustment is unnecessary (26).

The duration of maintenance therapy is 3 to 6 months, occasionally longer, depending on the cause of the DVT-UE (2, 29). In catheter-related thrombosis, particularly in the presence of a central catheter that remains functional and is still required, the catheter can continue to be used during anticoagulation. If the catheter be removed, anticoagulation should be continued for a further 3 months (29). In the presence of tumor-related DVT-UE, it is advisable to continue anticoagulation as long as the tumor disease remains active, in the absence of contraindications (2, 29). In this case LMWH is recommended for maintenance treatment (26, 30– 32, e7– e9).

Studies comparing DOAC with VKA have yielded no clear-cut results to date and have not specifically investigated DVT-UE or tumor-associated DVT. Moreover, the results, such as they are, seem contradictory. The CLOT trial showed significantly fewer thromboembolic events with dalteparin than with warfarin (p = 0.002)—a result that could not be confirmed in other studies (33). For example, the subsequent CATCH trial showed no comparable effect for tinzaparin versus VKA (34, 35).

Furthermore, the treatment goal has to be considered: is it thrombus dissolution, or prevention of disease progression or secondary complications? Complete dissolution of the thrombus is not often achieved. For example, a residual thrombus was demonstrated after conclusion of treatment in 82% of patients with DVT-UE (2). In this light, and in analogy with the treatment of DVT-LE, further procedures have been proposed:

- Local administration of fibrinolytics via catheter (catheter-directed thrombolysis, CDT) and percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy (PMT) have both been used in small case series of DVT-UE (2). Randomized controlled studies have concerned themselves exclusively with DVT-LE. For instance, Enden et al. compared anticoagulation alone with combined anticoagulation and CDT: At 6 months after treatment, regular blood flow was demonstrated in 65.9% of patients who had undergone additional CDT and in 47.4% of those treated with anticoagulation alone. The rate of PTS at 2 years was 41.1% with additional CDT compared with 55.6% for anticoagulation alone. The main complication was bleeding (20%). The transferability of these results to DVT-UE is questionable (36). It must be remembered that continuation of anticoagulation for 3 months after the end of CDT is recommended (29).

- The spectrum of interventional treatment procedures furthermore includes removal of the thrombus by means of mechanical crushing and aspiration with or without simultaneous lysis (pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis, PCDT/PMT), as well as the AngioJet and Trellis thrombectomy systems (2). While the AngioJet crushes the thrombus hydromechanically with a jet of liquid, in the Trellis method a lysing agent is administered between the two balloons of a dual-balloon catheter and dispersed by an oscillating wire, and lysis and fragmentation ensues locally (37). The success rates were 75% for the AngioJet and 70% for conventional CDT. The complication rates of the two techniques did not differ significantly (30).

The efficacy of the methods cannot be conclusively determined on the basis of the existing data. Interventional procedures are not yet routinely used to treat DVT-UE (30, 31, 38).

Prophylaxis

The need for prophylaxis depends on the individual risk, and both exposure—e.g., to acute illness and surgery—and disposition—e.g., congenital and acquired factors—must be taken into account. The risk of DVT is intermediate or high after lengthy surgery and in the presence of malignant disease and congenital thrombophilic disorders of hemostasis. Prophylaxis is necessary in these situations and can be achieved with heparins, fondaparinux, or DOAC (26, e10).

The efficacy of prophylaxis has been demonstrated for DVT-LE, but not so clearly for DVT-UE. The principal risk factors for DVT-UE are venous catheters and tumor disease (6, 8, 11, 12). A randomized trial by Verso et al. examined the impact of anticoagulation (LMWH versus placebo) in this risk constellation. Interestingly, no difference was found. Over an observation period of 6 weeks, the incidence of DVT-UE was 14.1% with enoxaparin and 18% with placebo (26, 39). In contrast, Monreal et al. showed that LWMH reduced the rate of DVT-UE (40). Joffe et al. found that only 20% of 387 patients with DVT-UE had received prophylactic anticoagulation (12). It therefore remains unclear whether prophylaxis has a positive effect on the occurrence of DVT-UE. However, prophylactic anticoagulation is indicated in any case, because the patients concerned are also threatened by DVT-LE.

Complications and prognosis

The typical complications of DVT-UE are: PTS, chronic venous insufficiency, thrombophlebitis, loss of venous access, and recurrence. Serious but rare events are superior vena cava syndrome (SVC syndrome) and pulmonary embolism (2, 7). SVC syndrome may result from propagation of a thrombus and leads to elevated venous pressure in the head, neck, and upper extremity (7, 10).

According to recent studies, the risk of recurrence of DVT-UE is ca. 9%. The risk is twofold for patients with tumor disease (18% versus 7.5%, hazard ratio 2.2 [0.6, 8.2]). Moreover, patients with catheter-associated DVT-UE show a higher rate of recurrence than patients without venous catheters (4).

Recurrences tend to occur on the ipsilateral side, and patients with recurrent DVT-UE often suffer further recurrences (26).

Owing to elevated venous pressure, PTS as a late complication of DVT-UE leads to chronic pain, edema, and functional limitation of the affected arm (2, 10, 26). Mild and moderate symptoms have been stated to occur in 28% and 8% of cases, respectively (1).

The data on frequency and importance of pulmonary embolism are sparse and heterogeneous (rates of 3 to 36%, asymptomatic in many cases) (2, 7, 19).

Various retrospective studies have shown high mortality rates among patients with DVT-UE. Margey et al. reported mortality of 15 to 50%, largely determined by the underlying disease (7). The above-mentioned study by Munos et al., for example, showed that the risk of death within 3 months is 8 times higher in DVT-UE patients with a tumor than in those without tumor disease (OR 7.7 [4.0, 16]) (32). Therefore, it is uncertain to what extent DVT-UE itself, as opposed to the life-threatening underlying disease, influences mortality.

Key Messages.

- The principal risk factors for deep vein thromboses of the upper extremity are (central) venous catheters (odds ratio [OR] 7.3) and malignant underlying disease (OR 18.1).

- Deep vein thromboses of the upper extremity are often asymptomatic or the clinical signs are unspecific.

- The gold standard for diagnosis is sonography.

- The treatment is oriented on that of deep vein thromboses of the lower extremity.

- Deep vein thromboses of the upper extremity are often less severe than those of the lower extremity.

eBOX 1. Methods.

- Search terms: “upper extremity DVT,” “upper extremity deep vein thrombosis,” “upper extremity vein thrombosis,” “Paget von Schroetter syndrome,” “Paget von Schroetter,” “Schroetter,” “Paget Schroetter,” and “Paget disease,” plus the equivalent terms in German.

- Inclusion of four publications after conclusion of the literature survey (May 2016).

- Inclusion of three publications in the course of revision.

- Literature selection by the authors (JH and AR) independently of one another on the basis of previously agreed inclusion criteria:

- Deep vein thromboses of the upper extremity as primary study goal or essential secondary study goal.

- Study type: randomized controlled studies, prospective and retrospective observational studies, cohort studies, case series (limited).

- Exclusion of publications about pediatric patients, publications about patients with anatomical malformations or stress-related thromboses, and reviews that contributed no information additional to that contained in the included primary publications.

- Publication in German or English.

- Assessment of study quality and risk of bias by the authors independently of one another. The quality of the studies used permitted only limited systematic assessment according to the Oxford scale. This state of affairs was factored into the analyses and the writing of the manuscript. Any differences of opinion between the authors regarding inclusion and weighting were settled by discussion and consensus or by consulting a third person (WB oder WM).

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Miesbach has received payments for lectures and reimbursement of congress attendance fees and travel costs from Bayer, Pfizer, and Leo.

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Bleker SM, van Es N, Kleinjan A, et al. Current management strategies and long-term clinical outcomes of upper extremity venous thrombosis. JTH. 2016;14:973–981. doi: 10.1111/jth.13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant JD, Stevens SM, Woller SC, et al. Diagnosis and management of upper extremity deep-vein thrombosis in adults. JTH. 2012;108:1097–1108. doi: 10.1160/TH12-05-0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3:123–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cote LP, Greenberg S, Caprini JA, et al. Comparisons between upper and lower extremity deep vein thrombosis: a review of the RIETE registry. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1076029616663847. pii: 1076029616663847 (epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Encke A, Haas S, Kopp I. The prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:532–538. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sajid MS, Ahmed N, Desai M, Baker D, Hamilton G. Upper limb deep vein thrombosis: a literature review to streamline the protocol for management. Acta Haematol. 2007;118:10–18. doi: 10.1159/000101700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margey R, Schainfeld RM. Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis: the oft-forgotten cousin of venous thromboembolic disease. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2011;13:146–158. doi: 10.1007/s11936-011-0113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JA, Zierler BK, Zierler RE. The risk factors and clinical outcomes of upper extremity deep vein thrombosis. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2012;46:139–144. doi: 10.1177/1538574411432145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone RH, Bress AP, Nutescu EA, Shapiro NL. Upper-extremity deep-vein thrombosis: a retrospective cohort evaluation of thrombotic risk factors at a university teaching hospital antithrombosis clinic. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:637–644. doi: 10.1177/1060028016649601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joffe HV, Goldhaber SZ. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Circulation. 2002;106:1874–1880. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000031705.57473.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spencer FA, Emery C, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Worcester Venous Thromboembolism Study: Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis: a community-based perspective. Am J Med. 2007;120:678–684. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joffe HV, Kucher N, Tapson VF, Goldhaber SZ. Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) FREE Steering Committee: Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis: a prospective registry of 592 patients. Circulation. 2004;110:1605–1611. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142289.94369.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baskin JL, Pui CH, Reiss U, et al. Management of occlusion and thrombosis associated with long-term indwelling central venous catheters. Lancet. 2009;374:159–169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60220-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grove JR, Pevec WC. Venous thrombosis related to peripherally inserted central catheters. JVIR. 2000;11:837–840. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans RS, Sharp JH, Linford LH, et al. Risk of symptomatic DVT associated with peripherally inserted central catheters. Chest. 2010;138:803–810. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Da Costa SS, Scalabrini Neto A, Costa R, Caldas JG, Martinelli Filho M. Incidence and risk factors of upper extremity deep vein lesions after permanent transvenous pacemaker implant: a 6-month follow-up prospective study. Pacing Clin Electrophysio. 2002;25:1301–1306. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, Rosendaal FR. Old and new risk factors for upper extremity deep venous thrombosis. JTH. 2005;3:2471–2478. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mino JS, Gutnick JR, Monteiro R, Anzlovar N, Siperstein AE. Line-associated thrombosis as the major cause of hospital-acquired deep vein thromboses: an analysis from National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data and a call to reassess prophylaxis strategies. Am J Surg. 2014;208:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kucher N. Clinical practice Deep-vein thrombosis of the upper extremities. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:861–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1008740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelberger RP, Kucher N. Management of deep vein thrombosis of the upper extremity. Circulation. 2012;126:768–773. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.051276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Es N, Bleker SM, di Nisio M, et al. A clinical decision rule and D-dimer testing to rule out upper extremity deep vein thrombosis in high-risk patients. Thromb Res. 2016;148:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Constans J, Salmi LR, Sevestre-Pietri MA, et al. A clinical prediction score for upper extremity deep venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:202–207. doi: 10.1160/TH07-08-0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Es N, van der Hulle T, Buller HR, et al. Is stand-alone D-dimer testing safe to rule out acute pulmonary embolism? JTH. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jth.13574. (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El Tabei L, Holtz G, Schurer-Maly C, Abholz HH. Accuracy in diagnosing deep and pelvic vein thrombosis in primary care: an analysis of 395 cases seen by 58 primary care physicians. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:761–766. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Nisio M, van Sluis GL, Bossuyt PM, Buller HR, Porreca E, Rutjes AW. Accuracy of diagnostic tests for clinically suspected upper extremity deep vein thrombosis: a systematic review. JTH. 2010;8:684–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.AWMF. S2k-Diagnostik und Therapie der Venenthrombose und der Lungenembolie. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/003-001.html (last accessed on 25 December 2016) [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Houten MM, van Grinsven R, Pouwels S, Yo LS, van Sambeek MR, Teijink JA. Treatment of upper-extremity outflow thrombosis. Phlebology. 2016;31:28–33. doi: 10.1177/0268355516632661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlitt A, Jambor C, Spannagl M, Gogarten W, Schilling T, Zwissler B. The perioperative management of treatment with anticoagulants and platelet aggregation inhibitors. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:525–532. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e419S–e494S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin PH, Zhou W, Dardik A, et al. Catheter-direct thrombolysis versus pharmacomechanical thrombectomy for treatment of symptomatic lower extremity deep venous thrombosis. Am J Surg. 2006;192:782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cynamon J, Stein EG, Dym RJ, Jagust MB, Binkert CA, Baum RA. A new method for aggressive management of deep vein thrombosis: retrospective study of the power pulse technique. JVIR. 2006;17:1043–1049. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000221085.25333.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munoz FJ, Mismetti P, Poggio R, et al. Clinical outcome of patients with upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis: results from the RIETE Registry. Chest. 2008;133:143–148. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee AY, Levine MN, Baker RI, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus a coumarin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:146–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee AY, Bauersachs R, Janas MS, et al. CATCH: a randomised clinical trial comparing long-term tinzaparin versus warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism in cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee AY, Kamphuisen PW, Meyer G, et al. Tinzaparin vs warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism in patients with active cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Enden T, Haig Y, Klow NE, et al. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:31–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61753-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vedantham S. Interventions for deep vein thrombosis: reemergence of a promising therapy. Am J Med. 2008;121:28–39. [Google Scholar]

- 38.O‘Sullivan GJ, Lohan DG, Gough N, Cronin CG, Kee ST. Pharmacomechanical thrombectomy of acute deep vein thrombosis with the Trellis-8 isolated thrombolysis catheter. JVIR. 2007;18:715–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verso M, Agnelli G, Bertoglio S, et al. Enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism associated with central vein catheter: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4057–4062. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monreal M, Alastrue A, Rull M, et al. Upper extremity deep venous thrombosis in cancer patients with venous access devices—prophylaxis with a low molecular weight heparin (Fragmin) JTH. 1996;75:251–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Schulman S, Kearon C, Kakkar AK, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2342–2352. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Schulman S, Kakkar AK, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Treatment of acute venous thromboembolism with dabigatran or warfarin and pooled analysis. Circulation. 2014;129:764–772. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, Brenner B, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2499–2510. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Buller HR, Prins MH, Lensin AW, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1287–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:799–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Hokusai VTEI, Buller HR, Decousus H, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1406–1415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Lyman GH, Khorana AA, Falanga A, et al. American Society of clinical oncology guideline: recommendations for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol Oncology. 2007;25:5490–5505. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Mandala M, Falanga A, Roila F, Group EGW. Management of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in cancer patients: ESMO clinical practice guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(6):vi85–vi92. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Khorana AA. The NCCN clinical practice guidelines on venous thromboembolic disease: strategies for improving VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized cancer patients. Oncologist. 2007;12:1361–1370. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-11-1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.AWMF. S3-Leitlinie Prophylaxe der venösen Thromboembolie (VTE) www.awmf.org/leitlinien/detail/ll/003-001.html (last accessed on 25 December 2016) [Google Scholar]

- E11.Flinterman LE, van der Meer FJ, Rosendaal FR, Doggen CJ. Current perspective of venous thrombosis in the upper extremity. JTH. 2008;6:1262–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Urschel HC Jr., Patel AN. Paget-Schroetter syndrome therapy: failure of intravenous stents. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1693–1696. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Urschel HC Jr., Razzuk MA. Paget-Schroetter syndrome: what is the best management? Ann Thorax Surg. 2000;69:1663–1668. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Schleyer AM, Jarman KM, Calver P, Cuschieri J, Robinson E, Goss JR. Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients: a descriptive study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:48–53. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Kovacs MJ, Kahn SR, Rodger M, et al. A pilot study of central venous catheter survival in cancer patients using low-molecular-weight heparin (dalteparin) and warfarin without catheter removal for the treatment of upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (the catheter study) JTH. 2007;5:1650–1653. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]