The Role of Cancer Stem Cells in Radiation Resistance (original) (raw)

Abstract

Cancer stem cells (CSC) are a distinct subpopulation within a tumor. They are able to self-renew and differentiate and possess a high capability to repair DNA damage, exhibit low levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and proliferate slowly. These features render CSC resistant to various therapies, including radiation therapy (RT). Eradication of all CSC is a requirement for an effective antineoplastic treatment and is therefore of utmost importance for the patient. This makes CSC the prime targets for any therapeutic approach. Albeit clinical data is still scarce, experimental data and first clinical trials give hope that CSC-targeted treatment has the potential to improve antineoplastic therapies, especially for tumors that are known to be treatment resistant, such as glioblastoma. In this review, we will discuss CSC in the context of RT, describe known mechanisms of resistance, examine the possibilities of CSC as biomarkers, and discuss possible new treatment approaches.

Keywords: cancer stem cells, radiation resistance, radiation therapy, DNA damage repair, reactive oxygen species, stem cell niche, quiescence

Introduction

Radiation therapy (RT) is one of the mainstays of cancer treatment. Roughly one half to two-third of all oncologic patients receive some form of RT in the course of their disease (1–5), either in a curative setting for primary treatment with or without other treatment modalities (i.e., surgery or chemotherapy, CHT) or in a palliative setting for the irradiation of symptomatic metastases. Importantly, the number of patients requiring RT is expected to increase in the foreseeable future (6). In short, RT exerts its effect by inducing DNA damage, either directly or indirectly via the production of water-derived radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (7–9), which then interact with macromolecules including DNA, lipids and proteins. As a consequence, DNA damage response (DDR) is initiated and leads to the activation of the DNA damage repair machinery as well as the induction of checkpoint kinase pathways, which delay cell cycle progression in order to facilitate DNA repair (10–13). In case the DNA is damaged beyond repair, DDR signaling induces apoptosis, senescence or mitotic catastrophe, all of which imply the loss of reproductive capacity of a cell (14–16). Consequently, if successful, RT hinders cancer cells from further proliferation. In theory, every (cancerous) cell can be killed with RT given a high enough dose. However, the surrounding healthy tissue limits the applicable dose (17). RT is usually a balancing act between giving enough dose to achieve local tumor control and only as much dose as the surrounding tissue can tolerate. Despite a very high local tumor control rate, a non-negligible rate of therapy failure still constitutes one of the major limitations in radiation oncology (18, 19). Insufficient response to irradiation (i.e., radiation resistance) contributes to residual cancer mass, which is the key driver of locoregional or distant recurrence, both of which are negatively influencing the patient's prognosis as local recurrence often is associated with metastatic spread, which is almost always fatal.

In recent years evidence has accumulated showing that multiple genetically diverse clones co-exist within various kinds of tumors (20–24). Not all cells within a tumor are equally sensitive to RT. Understanding the diverse radiosensitivity of different tumor cell subpopulations is very important. It challenges the common practice of employing macroscopic bulk tumor responses (as measured with medical imaging) as the primary endpoint for determining the effectiveness of an anti-neoplastic treatment. While this is certainly a very practical approach, it is only then true if the bulk tumor response represents the response of all cells within the tumor, including the most resistant subpopulation within the tumor. This is most likely not the case for most tumors because not all subpopulations are equally affected by the treatment. The stem cell model of cancer development may explain genetic, functional, and phenotypical differences, such as increased therapy resistance, within a tumor, even within the same tumor clone. Cancer stem cells (CSC), albeit difficult to identify, are believed to contribute to resistance to various oncological therapies, including RT (25–34), making them a primary target for anti-cancer therapy. Hence, a proper understanding of differential sensitivity of cancer cells, especially CSC, to irradiation is vital in order to develop new or improve existing anti-cancer therapies. Most research on CSC has been done in breast cancer and glioma (35, 36). However, as CSC differ between entities results cannot be transferred to other tumors, at least not without caution.

Cancer Stem Cells

Today, there are basically two largely accepted models for the origin of cancer: the standard (hierarchical) CSC model and the clonal evolution model. In the latter, genetic mutations accumulate with time and theoretically any cell can have tumorigenic potential (37). The CSC model describes a hierarchical organization of tumors with tumorigenic CSC at the apex which divide asymmetrically to form new CSC as well as differentiated non-tumorigenic progenies (34). Adding to the complexity of the CSC theory, is the fact that differentiation may be bidirectional. In this way, differentiated non-tumorigenic tumor cells may, instructed by niche signals, re-differentiate into CSC to replace lost stem cells. Even though data supporting the CSC hypothesis with its hierarchical organization of tumors is more solid, it is feasible that both, the CSC hypothesis and the clonal evolution model are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

The generation of CSC is not conclusively clarified, and several hypotheses exist (38). CSC may originate from normal stem cells, where random mutations during DNA replication may lead to them becoming malignant (39). Additionally, aberrant stromal signaling and pro-inflammatory conditions can lead to the malignant degeneration of normal stem cell (40). Alternatively, as stated earlier, CSC can be derived from differentiated cells. This can occur via genomic instability of tumor cells, horizontal genetic transfer, or microenvironmental signals. Genetic instability describes the acquisition of additional genetic mutations that provide any given differentiated tumor cell with stem cell traits so that it becomes a CSC (41). It is, however, unclear, whether stem cell traits shift from one cell to another in a stochastic manner during tumor evolution. In horizontal gene transfer, a normal stem cell may phagocyte fragmented DNA from tumor cells leading to their reprogramming and CSC formation (42). Microenvironmental signals include pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), which has been shown to facilitate dedifferentiation of non-CSC into CSC, or nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB), which maintains CSC numbers (43).

The frequency of CSC within a tumor is difficult to estimate and largely depends on the type of malignancy. In solid tumors, reported CSC rates are in the range from below 1% of all tumor cells to more than 80% (44–48). Similarly, the frequency of CSC in hematologic malignancies also displays a broad spectrum and ranges from <1% in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) up to over 80% in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) (49, 50). It has been shown in glioblastoma that CSC seem to reside predominantly in niches that are hypoxic, low in nutrients and have a low pH (51).

CSC are a distinct subpopulation within the heterogenous tumor mass and share several properties with normal stem cells (SC), the most important being the ability to self-renew (i.e., the potential of unlimited cell division) and the ability to give rise to more differentiated, mature cancer cells (34). Like in healthy tissue, stem cells initiate, promote, and maintain tumor development and growth (and re-growth after treatment) (52–55). It has been shown in glioma and breast cancer that the number of CSC in a tumor at the time of treatment is inversely correlated with clinical outcome (56, 57). Furthermore, repopulation of CSC after fractionated RT is one of the most important factors that determine local tumor control (58, 59). Therefore, inactivation of all CSC within a tumor is the prerequisite for a curative cancer treatment (60).

One major challenge regarding CSC is their correct identification as there is not one specific CSC marker, not least because of the high intra- and inter-tumor heterogeneity as well as tumor plasticity and the associated changes in genotype and phenotype. However, there are some cell surface marker that seem robust enough to use them as indicators for CSC. Two of these biomarkers are CD44 (found on CSC in cancers of the colon, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, breast, brain, lung, ovaries, prostate, liver, and the head and neck region) and CD133 (found in cancers of the colon, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, brain, lung, ovaries, prostate, liver, skin, and the head and neck region) (38, 61). Naturally, there are more surface molecules and usually combinations of these markers are used to identify and isolate CSC depending on the type of tumor that is investigated. It is important to emphasize that CSC differ between tumor entities, both phenotypically and functionally, and results from one type of cancer should not be translated to other types.

Radiocurability and Radiation Therapy Resistance

Following RT-induced DNA damage the balance of pro- and anti-apoptotic pathways skews toward cell death induction. However, in CSC pro-survival pathways seem to be more pronounced and protect these cells from cell death, rendering CSC radiation resistant (27). Radiation resistance of CSC may either be primary, i.e., due to the constitutive upregulation of certain molecules and pathways (see below). Alternatively, radiation resistance of CSC may be acquired. Following RT, as is the case with any other antineoplastic therapy, intratumoral heterogeneity can theoretically promote clonal evolution through Darwinian selection and lead to the development of adaptive responses with the result of more resistant, aggressive, and invasive tumors (62). CSC clones with genomic alterations that protect them against RT are selected for and continue to sustain the tumor (63). Indeed, it is known that RT preferentially kills non-CSC, thereby enriching the tumor for CSC (64). In addition, RT has been shown to induce the reprogramming of non-CSC in breast cancer as well as squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC) leads to the acquisition of functional CSC traits in order to compensate for cell loss in the stem cell compartment in response to cellular injury as is the case after RT (65, 66). Finally, RT leads to the recruitment of CSC in breast cancer from a quiescent state into the cell cycle (67, 68). In this way, RT contributes to the acquired or adaptive radioresistance via selective repopulation from the surviving CSC.

The number of CSC within a tumor predicts the radiation dose needed to eradicate the tumor. Therefore, in tumors with a higher proportion of CSC a given dose of irradiation leads to a lower probability of local control as compared to tumors with fewer CSC (69–71). From a clinical point of view, this implies a dose-volume dependency, as radiocurability of tumors inversely correlates with tumor volume (72) and with intrinsic radiosensitivity in vitro (73). Furthermore, the probability of successful irradiation also correlates with the number, density, and intrinsic radiosensitivity of CSC (60, 71) and the absolute number of CSC increases with tumor volume (70–72, 74). Importantly, survival of one single CSC after RT can lead to tumor relapse. Hence, eradication of the entire CSC population is of utmost importance for the patient. Nonetheless, one must keep in mind that CSC differ between tumor types and there is no general radiation resistance of CSC, as many patients can be cured with current concepts of conventional RT.

Cellular Factors for CSC Radioresistance

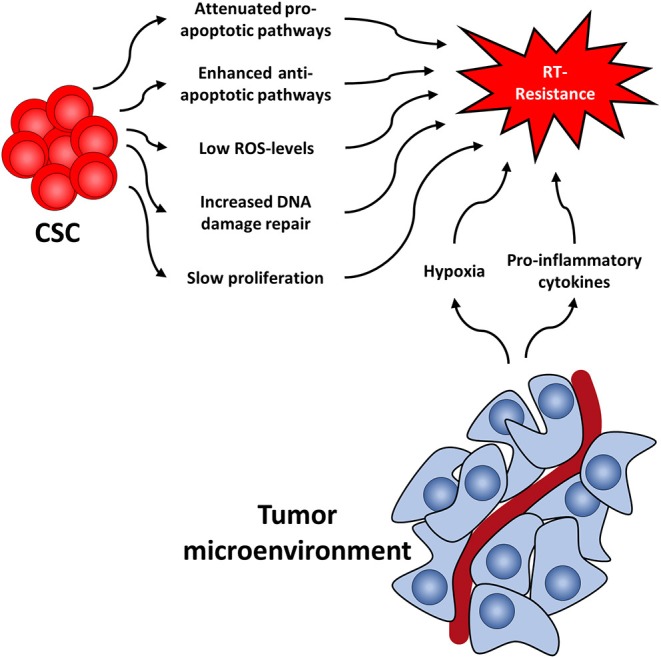

Several cellular features render CSC radioresistant. In the following, we will discuss the best-studied cellular factors, which include low levels of ROS, increased DNA damage repair capacity, or quiescence (Figure 1). These are common characteristics of healthy SC and CSC alike, presumably to protect their DNA from stress-induced damages.

Figure 1.

Cancer stem cell-related factors as well as the tumor microenvironment both contribute to radioresistance and reveal new therapeutic approaches.

ROS are involved in various physiological processes, such as proliferation, differentiation, metabolism, apoptosis, angiogenesis, wound healing, or motility (75, 76). Intracellular ROS levels are tightly and continuously regulated by ROS scavengers, which include superoxide dismutase, superoxide reductase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, glutathione reductase, or apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease/redox effector factor (Ape1/Ref-1, also known as APEX1) (77). There is a multitude of publications showing that ROS scavengers are upregulated and highly efficient in CSC of various tumors (78–83) leading to low levels of ROS and protecting CSC from RT-induced cell death, as ROS is essential for the effect of RT (84). This protective effect of upregulated ROS scavengers even outweighs the effect of oxygen, a known potent radiosensitizer (85). Along this line, it has been shown that CSC produce less ROS upon radiation compared to non-CSC (86).

Secondly, DNA damage repair capacity following RT, especially regarding DNA double strand breaks (DSB), has been shown to be higher in CSC as compared to their non-tumorigenic counterparts (25, 87–90). This has been shown in CSC of several tumors, including glioma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, prostate, lung, and breast cancer, and is mainly attributed to the activation of checkpoint-pathways in response to RT (90–98). The resulting delayed cell cycle progression allows for repair of the DNA damage. Interestingly, CSC have been shown to repair DNA damage preferably via homologous recombination (HR) instead of non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), the latter being less accurate and more error-prone than HR (25, 99–101). A comprehensive review on DNA damage repair in CSC has recently been published (102).

Third, it has been shown in various studies that CSC proliferate more slowly than further differentiated cancer cells (78, 103, 104). This is of importance as RT is known to be more effective in killing rapidly proliferating tumor cells as compared to slowly dividing (i.e., quiescent or dormant) cells and quiescence is associated with relative radiation resistance (105, 106). This way, non-proliferating cells survive therapeutic irradiations and remain quiescent for a various amount of time, which can range from weeks (78, 104) to even decades (107, 108). Once they continue to proliferate, these cells can cause a recurrence.

Tumor Microenvironment

Similar to healthy stem cells, CSC reside in specific niches that provide microenvironmental factors such as autocrine signaling and signals coming from stromal fibroblasts (cancer associated fibroblasts, CAF), immune cells, endothelial cells, and extracellular matrix components (109, 110). The exact composition of the niche is not well-defined for most tumors, as are the exact supporting signals. It is known, however, that the niche supplies CSC with oxygen and nutrients, supports stem cell functions, protects from insults such as radiation, and regulates responsiveness to a therapy (111). For instance, in breast cancer it has been shown that deregulation of the stem cell niche by increased expression of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) can initiated and promote malignant stem cell transformation (112). Furthermore, at least in glioblastoma tumor samples, there are different types of niches, such as hypoxic peri-arteriolar niches, peri-vascular niches, peri-hypoxic niches, peri-immune niches, and extracellular niches (113). Whether other types of cancer have different types of niches, and what therapeutic implications this finding might have, still needs to be elucidated.

Like the tumor itself, the tumor microenvironment also responds to RT (114) (Figure 1). For instance, it has been shown that CAFs acquire a pro-malignant phenotype after RT of in colorectal cancer samples (115–117). Furthermore, CAFs induce autophagy following irradiation of lung cancer and melanoma cell lines leading to enhanced cancer cell recovery and tumor re-growth (118).

Additionally, RT induces pro-inflammatory cytokines in the tumor microenvironment (119, 120), including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), interleukin 1β (IL1β), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), C-X-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), and interleukin-6 (IL6). This leads to the upregulation of ROS scavengers in CSC (7) and activation of downstream STAT3 signaling, a cascade known to promote self-renewal in embryonic stem cells neu (121). Furthermore, this promotes survival of tumor cells, facilitates tumor regrowth and leads to the development of highly invasive CSC phenotypes (122, 123).

Another mechanism by which the niche protects CSC is hypoxia. Oxygen is a potent radiosensitizer and is needed for radiation-induced ROS production and in further consequence for cell death. Lack of oxygen is known to increase radiation resistance (124–126) and has been associated with early relapse after RT. Consequently, increasing tumor oxygenation improves the response to RT (127–129). In addition to the absolute lack of oxygen and the resulting low ROS levels, CSC in hypoxic niches upregulate ROS scanvengers (7, 130, 131), thereby further lowering ROS levels compared to normoxic CSC. This in turn leads to the activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) signaling route (132–134). Interestingly, HIF1α and the respective regulated cytokines have also been shown to be increased following RT (135). HIF are important master regulators of transcription of hypoxia response elements, which activates pro-survival pathways such as the Notch, wingless and INT-1 (WNT) and Hedgehog pathway (136–138). These pathways have been shown to be important for CSC maintenance and can lead to radioresistance and accelerated repopulation of CSC during or after treatment, as has been shown in glioma, breast cancer, and prostate cancer (97, 139–142).

CSC as Biomarker

There is accumulating evidence that CSC could be used as biomarkers to predict treatment response and estimate the likelihood of tumor relapse in cancer patients. It has been shown in various tumors, including urothelial cancer (143–145), gastric cancer (146–150), pancreatic cancer (151, 152), HNSCC (153–155), glioma (156–159), thyroid carcinoma (160, 161), hepatocellular carcinoma (162, 163), breast cancer (164), and lung cancer (165). However, it has been shown in ovarian cancer that the prognostic value of CD44 may depend on its isoform, with the transmembrane form indicating a better prognosis, while the presence of the soluble extracellular domain was associated with a worse prognosis (166). In a recent meta-analysis, overall CD44 expression in ovarian cancer was associated with a high TNM stage and a poor 5 year overall survival (167). Along this line, low expression of CD44 was shown to be an independent factor of poor prognosis in ovarian mucinous carcinoma (168). Interestingly, in breast cancer, it has been shown that CD44 was associated with longer disease-free-survival (DFS) in estrogen-receptor (ER) positive women, while CD44 positive tumors were associated with poor outcome in ER-negative patients (169). In a recent meta-analysis, Han and colleagues tried to generalize the prognostic significance of CD44 and its variant isoforms in advanced cancer patients. In this analysis of 15 articles with more than 1,200 patients, CD44 was slightly linked to a worse overall survival, but there was no correlation between CD44 expression and DFS, recurrence-free survival (RFS), or progression-free survival (PFS) (170).

Two studies from the German Cancer Consortium Radiation Oncology Group (DKTK-ROG) have shown that CSC marker expression is a potential biomarker for favorable prognosis in patients with locally advanced HNSCC, both after primary chemoradiotherapy (171) as well as following post-operative chemoradiotherapy (172). In a recent validation study from the same group, the addition of CD44 could further improve the prognostic performance of models using tumor volume, p16 status, and N stage (173).

Activity of the 26S proteasome, a protease complex with regulatory functions in cell cycle, DNA repair, and cell survival, is another CSC marker (131, 174–177). In this regard, low 26S proteasome activity correlated with high self-renewal capacity and high tumorigenicity in HNSCC cell lines (178). A high 26S proteasome activity correlated with a longer survival and higher local control rates in patients who underwent chemoradiotherapy for HNSCC (95).

Another potential biomarker, especially for glioma, might be the stem cell marker CD133. In a recent meta-analysis including 21 articles with more than 1,550 patients, CD133 expression correlated with higher grade of gliomas and worse prognosis in glioma patients (179). Interestingly, in a recent in vitro analysis in glioma cell lines, CD133 expression could be downregulated by vincristine, a common chemotherapeutic drug (180). In a study by Wu and colleagues, CD133 promotor methylation was a significant prognostic factor for adverse PFS and overall survival, while there was no correlation between CD133 protein expression and survival (181). Additionally, there are other publications that showed no association of CD133 protein expression with survival (182, 183).

Novel Treatment Approaches

Increased understanding of CSC has led to new ideas for improving cancer therapy. It certainly seems feasible to combine conventional anti-neoplastic therapy (e.g., RT or CHT) to target the tumor bulk with CSC specific treatment in order to improve outcome as compared to monotherapies (184, 185). Inactivation of even only limited numbers of CSC might significantly improve local tumor control probability (70). However, the assumed plasticity of the CSC and non-CSC compartments, especially the possible shift of stem cell traits, increases the complexity of treatment responses of tumors. In an ideal situation where the CSC population is strictly static, drugs that specifically target CSC would lead to a massively improved treatment outcome, possibly even without the need of additional treatment modalities (e.g., RT or CHT). However, CSC plasticity render a CSC-targeting monotherapy virtually impossible, since after treatment, non-CSC may gain CSC traits and repopulate the tumor. Additionally, regarding the current CSC marker and their uncertainty in robustly identifying CSC, and to sufficiently distinguish them from healthy SC, a strictly CSC-based therapy seems to be still a long way off.

One conceivable possibility to eliminate CSC with RT more efficiently is to increase the applied dose. This is usually not feasible for the whole tumor due to dose constraints of the surrounding healthy tissue. Therefore, visualization of CSC could allow for larger doses of radiation in CSC rich regions while still respecting the dose constraints. Indeed, there are first studies in mice, where CD133+ glioblastoma cells could be detected non-invasively by PET and near-infrared fluorescence molecular tomography using antibody-labeled tracer (186). Subsequently, the same group showed that near-infrared photoimmunotherapy using phototoxic antibody conjugates was efficient not only in rendering CD133+ glioblastoma cells visible but also in inducing cell death (187).

Another means by which RT can be utilized to eliminate CSC more efficiently is the use of types of irradiation other than commonly used photon beams (188, 189). Particle beams of protons and carbon ions are being increasingly used due to their advantageous depth-dose curve and their higher cell-killing efficiency compared with photons (190). Preclinical studies deliver promising results when using proton irradiation. For instance, in CSC-like cells from two human NSCLC cell lines, irradiation with protons was more efficient than photon treatment in reducing cell viability. clonogenic survival, cell migration, and invasiveness, while increasing apoptosis and ROS levels (191). Furthermore, proton irradiation has been shown to be more cytotoxic, induce higher and longer cell cycle arrest, reduce cell adhesion and migration ability, and reduce the overall population of CSC in NSCLC cell lines compared to photon irradiation (192). Finally, in glioma stem cells from glioblastoma patients, similar results have been achieved (193). In this study, particle irradiation with protons and carbon ions has been shown to be more effective in cell killing compared to photons, likely because of the different quality of the induced DNA damage. Indeed, compared to photons, proton beam irradiation has been shown to increase ROS levels, induce more single and double strand DNA breaks, less DNA damage repair (as measured by H2AX phosphorylation), and decreased cell cycle recovery which led to increased apoptosis (194). Interestingly, primary human glioma stem cells that were resistant to photon treatment could be rendered sensitive with carbon ion irradiation via impaired capacity to repair carbon ion induced DNA double strand breaks (195). Importantly, this study also showed an individual heterogeneity in the amount and radiosensitivity of glioma stem cells from different patients, further complicating a one size fits all treatment. In the recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors have greatly improved treatment outcomes for many cancers. In this regard, it has been shown that proton irradiation increased sensitivity of CSC from different cell lines, such as breast or prostate cancer, to cytotoxic T-cell killing (196). These findings offer a rationale for the combined use of proton irradiation with immunotherapy. Another important aspect of particle irradiation is the reduced dependence from tissue oxygenation. While photon irradiation is always strongly affected by the presence of oxygen in the induction and maintenance of DNA damage, high LET particle beams can be much less hindered by hypoxic conditions, which are often found in solid tumors. For example, Tinganelli et al. (197) showed the survival of mammalian cells exposed to different types of particle radiation in various oxygen concentrations, leading to a hypoxia-adapted irradiation plan. Hence, it seems feasible and promising to use particle irradiation in order to counteract tumor hypoxia. Taken together, these results suggest a potential advantage of particle beam irradiations in CSC eradication, eventually in combination with conventional photon irradiation: photon beam irradiation to the whole tumor and a boost of particle beams to hypoxic areas within the tumor. Alternatively, one can ideally use a properly optimized plan of carbon or oxygen beam, or, considering the potential of the most advanced particle centers, a multiple-ion irradiation (198). Another new strategy in combating glioblastoma is the interference with metabolic pathways. It has been shown that dichloroacetate (DCA), an orphan drug, has been shown to switch the metabolism in freshly isolated glioma stem cells from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to cytoplasmic glycolysis, which in turn increased mitochondrial ROS and induced apoptosis (199). In the same study, glioblastoma patients treated with the standard of care (i.e., radiation therapy and temozolomide) received oral DCA for up to 15 months. The drug was well-tolerated, and some patients showed prolonged radiologic stabilization and decelerated tumor progression. Additionally, DCA, in combination with PENAO [4-(N-(S-penicillaminylacetyl)amino) phenylarsonous acid] has been shown to increase radiosensitivity of glioma cells by inducing a cell cycle arrest, elevating ROS production, depolarizing mitochondrial membrane potential, increasing DNA damage, and inducing apoptosis (200).

Early experiments with CSC-directed antibodies have shown promising results. Gurtner et al. (201) used antibodies directed against CD44 that were loaded with highly cytotoxic drugs. In this experimental setting, these antibodies, combined with irradiation, led to an improved local tumor control. Considering the high expression of ROS scavengers in CSC, it may be reasonable to target these ROS scavengers. Pharmacological depletion of ROS scavengers (e.g., by treatment with buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), has been shown to reduce radiation resistance as well as clonogenic properties of CSC in breast cancer and HNSCC (202, 203). Additionally, the use of antioxidants during RT, which reduce ROS levels, might prove nonsensical, as high ROS levels are needed, especially in CSC, in order to facilitate RT-induced cell death.

Checkpoint pathways can be inhibited pharmacologically to prevent delayed cell cycle progression and hamper DNA damage repair in CSC as has been shown in glioma and prostate cancer (98, 204). Additionally, direct inhibition of DNA damage repair signaling has been shown to reduce radiation resistance in breast cancer CSC (92). Chemical inhibition of Notch signaling, a developmental pathway that is known to be essential for tissue homeostasis (205) has been shown to increase radiosensitivity in glioma CSC (206). However, most clinical studies regarding these signaling pathways focus on chemotherapy (207). There is preclinical data in mice with glioblastoma multiforme that were treated with RT and temozolomide combined with a Notch inhibitor. In this study, Notch inhibition had an anti-glioma stem cell effect which provided a survival benefit (208). Regarding clinical data, there is an ongoing trial testing a Notch inhibitor combined with whole-brain RT or stereotactic cranial RT [NCT01217411], but so far there are no results of this study available.

Overcoming tumor hypoxia is another method to improve cancer therapy. Nitroimidazole derivates can mimic the effect of oxygen and can produce reactive species in hypoxic cells. There have already been clinical trials with a clinically relevant sensitization and low toxicity (209, 210). Nitric oxide (NO) is also able to mimic oxygen and thereby to increase radiosensitivity in hypoxic tissue. In a first clinical trial, the NO donor glyceryl-trinitrate (GTN) has been shown to reduce hypoxia-induced progression of prostate cancer (211). Taken together, targeting the hypoxic niche of CSC might eventually improve treatment outcome following RT. An important task in this regard will be the correct identification of CSC for a given tumor, since CSC can differ between tumors both functionally/metabolically as well as phenotypically. Additionally, CSC share many properties and surface molecules with normal stem cells, making a clear distinction difficult and increasing the risk of unwanted side effects. Finally, it seems conceivable that drugs that interfere with spontaneous as well as RT-induced reprogramming of non-CSC into CSC could also be of value for cancer treatment. However, it needs to be investigated if these mechanisms are the same in normal steam cells and CSC before such drugs can be developed.

Another interesting approach to amplify the effect of radiation therapy, particularly on CSC, is the use of nanostructures that, after being endocytosed by cancer cells and following irradiation, release secondary electrons and large amounts of ROS (212). This could be especially effective in CSC, where ROS levels are generally lower. In this study, a significant tumor growth suppression and overall improvement in survival rate has been demonstrated in an in vitro and in vivo model of triple negative breast cancer.

Conclusion

There is growing evidence of a radiation resistance tumor subpopulation with increased DNA damage repair, increased survival signaling, and decreased ROS, that is furthermore protected by its environment. With refined understanding of these cells and their role in development and progression of cancer come new possibilities to improve cancer therapy. Targeting CSC, based on phenotype or function, seems promising. Nonetheless, we are just at the beginning and clinical data is still scarce. Major issues concern their correct identification and reliable distinction from healthy cells and the plasticity of the CSC department. It will be exciting to see which position CSC-specific therapies will occupy within the row of current anti-neoplastic therapies.

Author Contributions

CA and JM performed the literature research. CA wrote the manuscript. I-IS and UG supervised the project.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Delaney G, Jacob S, Featherstone C, Barton M. The role of radiotherapy in cancer treatment: estimating optimal utilization from a review of evidence-based clinical guidelines. Cancer. (2005) 104:1129–37. 10.1002/cncr.21324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tyldesley S, Delaney G, Foroudi F, Barbera L, Kerba M, Mackillop W. Estimating the need for radiotherapy for patients with prostate, breast, and lung cancers: verification of model estimates of need with radiotherapy utilization data from British Columbia. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2011) 79:1507–15. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang-Salomons J, Mackillop WJ. Estimating the lifetime utilization rate of radiotherapy in cancer patients: the multicohort current utilization table (MCUT) method. Comp Methods Programs Biomed. (2008) 92:99–108. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez A, Borras JM, Lopez-Torrecilla J, Algara M, Palacios-Eito A, Gomez-Caamano A, et al. Demand for radiotherapy in Spain. Clin Transl Oncol. (2017) 19:204–10. 10.1007/s12094-016-1525-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chierchini S, Ingrosso G, Saldi S, Stracci F, Aristei C. Physician And patient barriers to radiotherapy service access: treatment referral implications. Cancer Manag Res. (2019) 11:8829–33. 10.2147/CMAR.S168941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borras JM, Lievens Y, Barton M, Corral J, Ferlay J, Bray F, et al. How many new cancer patients in Europe will require radiotherapy by 2025? An ESTRO-HERO analysis. Radiother Oncol. (2016) 119:5–11. 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holley AK, Miao L, Clair DK, Clair WH. Redox-modulated phenomena and radiation therapy: the central role of superoxide dismutases. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2014) 20:1567–89. 10.1089/ars.2012.5000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mladenov E, Magin S, Soni A, Iliakis G. DNA double-strand break repair as determinant of cellular radiosensitivity to killing and target in radiation therapy. Front Oncol. (2013) 3:113. 10.3389/fonc.2013.00113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srinivas US, Tan BWQ, Vellayappan BA, Jeyasekharan AD. ROS and the DNA damage response in cancer. Redox Biol. (2019) 25:101084. 10.1016/j.redox.2018.101084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan MA, Lawrence TS. Molecular pathways: overcoming radiation resistance by targeting DNA damage response pathways. Clin Cancer Res. (2015) 21:2898–904. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikitaki Z, Michalopoulos I, Georgakilas AG. Molecular inhibitors of DNA repair: searching for the ultimate tumor killing weapon. Future Med Chem. (2015) 7:1543–58. 10.4155/fmc.15.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turgeon MO, Perry NJS, Poulogiannis G. DNA damage, repair, and cancer metabolism. Front Oncol. (2018) 8:15. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatterjee N, Walker GC. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environ Mol Mutagen. (2017) 58:235–63. 10.1002/em.22087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roos WP, Thomas AD, Kaina B. DNA damage and the balance between survival and death in cancer biology. Nat Rev Cancer. (2016) 16:20–33. 10.1038/nrc.2015.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Han S, Zhu J, Wang X, Li Y, Wang Z, et al. Proton versus photon radiation-induced cell death in head and neck cancer cells. Head Neck. (2019) 41:46–55. 10.1002/hed.25357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philchenkov A. Radiation-Induced cell death: signaling and pharmacological modulation. Crit Rev Oncog. (2018) 23:13–37. 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2018026148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanna GG, Murray L, Patel R, Jain S, Aitken KL, Franks KN, et al. UK consensus on normal tissue dose constraints for stereotactic radiotherapy. Clin Oncol. (2018) 30:5–14. 10.1016/j.clon.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begg AC, Stewart FA, Vens C. Strategies to improve radiotherapy with targeted drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. (2011) 11:239–53. 10.1038/nrc3007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa K, Yoshioka Y, Isohashi F, Seo Y, Yoshida K, Yamazaki H. Radiotherapy targeting cancer stem cells: current views and future perspectives. Anticancer Res. (2013) 33:747–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Math M, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. (2012) 366:883–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sottoriva A, Spiteri I, Piccirillo SG, Touloumis A, Collins VP, Marioni JC, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity in human glioblastoma reflects cancer evolutionary dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2013) 110:4009–14. 10.1073/pnas.1219747110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andor N, Graham TA, Jansen M, Xia LC, Aktipis CA, Petritsch C, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of the extent and consequences of intratumor heterogeneity. Nat Med. (2016) 22:105–13. 10.1038/nm.3984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prasetyanti PR, Medema JP. Intra-tumor heterogeneity from a cancer stem cell perspective. Mol Cancer. (2017) 16:41. 10.1186/s12943-017-0600-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meacham CE, Morrison SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature. (2013) 501:328–37. 10.1038/nature12624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rycaj K, Tang DG. Cancer stem cells and radioresistance. Int J Radiat Biol. (2014) 90:615–21. 10.3109/09553002.2014.892227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adorno-Cruz V, Kibria G, Liu X, Doherty M, Junk DJ, Guan D, et al. Cancer stem cells: targeting the roots of cancer, seeds of metastasis, and sources of therapy resistance. Cancer Res. (2015) 75:924–9. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peitzsch C, Kurth I, Kunz-Schughart L, Baumann M, Dubrovska A. Discovery of the cancer stem cell related determinants of radioresistance. Radiother Oncol. (2013) 108:378–87. 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang JC. Cancer stem cells: role in tumor growth, recurrence, metastasis, and treatment resistance. Medicine. (2016) 95(1 Suppl. 1):S20–5. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinbichler TB, Dudas J, Skvortsov S, Ganswindt U, Riechelmann H, Skvortsova II. Therapy resistance mediated by cancer stem cells. Semin Cancer Biol. (2018) 53:156–67. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phi LTH, Sari IN, Yang YG, Lee SH, Jun N, Kim KS, et al. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) in drug resistance and their therapeutic implications in cancer treatment. Stem Cells Int. (2018) 2018:5416923. 10.1155/2018/5416923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lytle NK, Barber AG, Reya T. Stem cell fate in cancer growth, progression and therapy resistance. Nat Rev Cancer. (2018) 18:669–80. 10.1038/s41568-018-0056-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prieto-Vila M, Takahashi RU, Usuba W, Kohama I, Ochiya T. Drug resistance driven by cancer stem cells and their niche. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:2574. 10.3390/ijms18122574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doherty MR, Smigiel JM, Junk DJ, Jackson MW. Cancer stem cell plasticity drives therapeutic resistance. Cancers. (2016) 8:8. 10.3390/cancers8010008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Batlle E, Clevers H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med. (2017) 23:1124–34. 10.1038/nm.4409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradshaw A, Wickremsekera A, Tan ST, Peng L, Davis PF, Itinteang T. Cancer stem cell hierarchy in glioblastoma multiforme. Front Surg. (2016) 3:21. 10.3389/fsurg.2016.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bai X, Ni J, Beretov J, Graham P, Li Y. Cancer stem cell in breast cancer therapeutic resistance. Cancer Treat Rev. (2018) 69:152–63. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rich JN. Cancer stem cells: understanding tumor hierarchy and heterogeneity. Medicine. (2016) 95(1 Suppl 1):S2–7. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atashzar MR, Baharlou R, Karami J, Abdollahi H, Rezaei R, Pourramezan F, et al. Cancer stem cells: a review from origin to therapeutic implications. J Cell Physiol. (2020) 235:790–803. 10.1002/jcp.29044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B. Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science. (2015) 347:78–81. 10.1126/science.1260825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White AC, Lowry WE. Refining the role for adult stem cells as cancer cells of origin. Trends Cell Biol. (2015) 25:11–20. 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beck B, Blanpain C. Unravelling cancer stem cell potential. Nat Rev Cancer. (2013) 13:727–38. 10.1038/nrc3597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bjerkvig R, Tysnes BB, Aboody KS, Najbauer J, Terzis AJ. Opinion: the origin of the cancer stem cell: current controversies and new insights. Nat Rev Cancer. (2005) 5:899–904. 10.1038/nrc1740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lau EY, Ho NP, Lee TK. Cancer stem cells and their microenvironment: biology and therapeutic implications. Stem Cells Int. (2017) 2017:3714190. 10.1155/2017/3714190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joshua B, Kaplan MJ, Doweck I, Pai R, Weissman IL, Prince ME, et al. Frequency of cells expressing CD44, a head and neck cancer stem cell marker: correlation with tumor aggressiveness. Head Neck. (2012) 34:42–9. 10.1002/hed.21699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, Dick JE. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature. (2007) 445:106–10. 10.1038/nature05372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. (2004) 432:396–401. 10.1038/nature03128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quintana E, Shackleton M, Sabel MS, Fullen DR, Johnson TM, Morrison SJ. Efficient tumour formation by single human melanoma cells. Nature. (2008) 456:593–8. 10.1038/nature07567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2003) 100:3983–8. 10.1073/pnas.0530291100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. (1994) 367:645–8. 10.1038/367645a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kong Y, Yoshida S, Saito Y, Doi T, Nagatoshi Y, Fukata M, et al. CD34+CD38+CD19+ as well as CD34+CD38-CD19+ cells are leukemia-initiating cells with self-renewal capacity in human B-precursor ALL. Leukemia. (2008) 22:1207–13. 10.1038/leu.2008.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mondal S, Bhattacharya K, Mandal C. Nutritional stress reprograms dedifferention in glioblastoma multiforme driven by PTEN/Wnt/Hedgehog axis: a stochastic model of cancer stem cells. Cell Death Discov. (2018) 4:110. 10.1038/s41420-018-0126-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen J, Li Y, Yu TS, McKay RM, Burns DK, Kernie SG, et al. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. (2012) 488:522–6. 10.1038/nature11287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Driessens G, Beck B, Caauwe A, Simons BD, Blanpain C. Defining the mode of tumour growth by clonal analysis. Nature. (2012) 488:527–30. 10.1038/nature11344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schepers AG, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, van den Born M, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, et al. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science. (2012) 337:730–5. 10.1126/science.1224676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell. (2014) 14:275–91. 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vlashi E, Lagadec C, Vergnes L, Matsutani T, Masui K, Poulou M, et al. Metabolic state of glioma stem cells and nontumorigenic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:16062–7. 10.1073/pnas.1106704108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ginestier C, Hur MH, Charafe-Jauffret E, Monville F, Dutcher J, Brown M, et al. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell. (2007) 1:555–67. 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baumann M, Dorr W, Petersen C, Krause M. Repopulation during fractionated radiotherapy: much has been learned, even more is open. Int J Radiat Biol. (2003) 79:465–7. 10.1080/0955300031000160259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hessel F, Krause M, Petersen C, Horcsoki M, Klinger T, Zips D, et al. Repopulation of moderately well-differentiated and keratinizing GL human squamous cell carcinomas growing in nude mice. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2004) 58:510–8. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.09.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Butof R, Dubrovska A, Baumann M. Clinical perspectives of cancer stem cell research in radiation oncology. Radiother Oncol. (2013) 108:388–96. 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abbaszadegan MR, Bagheri V, Razavi MS, Momtazi AA, Sahebkar A, Gholamin M. Isolation, identification, and characterization of cancer stem cells: a review. J Cell Physiol. (2017) 232:2008–18. 10.1002/jcp.25759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kreso A, O'Brien CA, van Galen P, Gan OI, Notta F, Brown AM, et al. Variable clonal repopulation dynamics influence chemotherapy response in colorectal cancer. Science. (2013) 339:543–8. 10.1126/science.1227670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Diehn M, Cho RW, Clarke MF. Therapeutic implications of the cancer stem cell hypothesis. Semin Radiat Oncol. (2009) 19:78–86. 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martins-Neves SR, Cleton-Jansen AM, Gomes CMF. Therapy-induced enrichment of cancer stem-like cells in solid human tumors: where do we stand? Pharmacol Res. (2018) 137:193–204. 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lagadec C, Vlashi E, Della Donna L, Dekmezian C, Pajonk F. Radiation-induced reprogramming of breast cancer cells. Stem Cells. (2012) 30:833–44. 10.1002/stem.1058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao X, Sishc BJ, Nelson CB, Hahnfeldt P, Bailey SM, Hlatky L. Radiation-Induced reprogramming of pre-senescent mammary epithelial cells enriches putative CD44(+)/CD24(-/low) stem cell phenotype. Front Oncol. (2016) 6:138. 10.3389/fonc.2016.00138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vlashi E, Kim K, Lagadec C, Donna LD, McDonald JT, Eghbali M, et al. In vivo imaging, tracking, and targeting of cancer stem cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2009) 101:350–9. 10.1093/jnci/djn509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lagadec C, Vlashi E, Della Donna L, Meng Y, Dekmezian C, Kim K, et al. Survival and self-renewing capacity of breast cancer initiating cells during fractionated radiation treatment. Breast Cancer Res. (2010) 12:R13. 10.1186/bcr2479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baumann M, Krause M, Thames H, Trott K, Zips D. Cancer stem cells and radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Biol. (2009) 85:391–402. 10.1080/09553000902836404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baumann M, Krause M, Hill R. Exploring the role of cancer stem cells in radioresistance. Nat Rev Cancer. (2008) 8:545–54. 10.1038/nrc2419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yaromina A, Krause M, Thames H, Rosner A, Krause M, Hessel F, et al. Pre-treatment number of clonogenic cells and their radiosensitivity are major determinants of local tumour control after fractionated irradiation. Radiother Oncol. (2007) 83:304–10. 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dubben HH, Thames HD, Beck-Bornholdt HP. Tumor volume: a basic and specific response predictor in radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. (1998) 47:167–74. 10.1016/S0167-8140(97)00215-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gerweck LE, Zaidi ST, Zietman A. Multivariate determinants of radiocurability. I: prediction of single fraction tumor control doses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (1994) 29:57–66. 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90226-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baumann M, Dubois W, Suit HD. Response of human squamous cell carcinoma xenografts of different sizes to irradiation: relationship of clonogenic cells, cellular radiation sensitivity In vivo, and tumor rescuing units. Radiat Res. (1990) 123:325–30. 10.2307/3577740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Di Meo S, Reed TT, Venditti P, Victor VM. Role of ROS and RNS sources in physiological and pathological conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2016) 2016:1245049. 10.1155/2016/1245049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang J, Wang X, Vikash V, Ye Q, Wu D, Liu Y, et al. ROS and ROS-mediated cellular signaling. Oxid Med Cell Longev. (2016) 2016:4350965. 10.1155/2016/4350965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Skvortsova I, Debbage P, Kumar V, Skvortsov S. Radiation resistance: cancer stem cells (CSCs) and their enigmatic pro-survival signaling. Semin Cancer Biol. (2015) 35:39–44. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Skvortsov S, Jimenez CR, Knol JC, Eichberger P, Schiestl B, Debbage P, et al. Radioresistant head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells: intracellular signaling, putative biomarkers for tumor recurrences and possible therapeutic targets. Radiother Oncol. (2011) 101:177–82. 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Skvortsov S, Debbage P, Skvortsova I. Proteomics of cancer stem cells. Int J Radiat Biol. (2014) 90:653–8. 10.3109/09553002.2013.873559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang Y, Martin SG. Redox proteins and radiotherapy. Clin Oncol. (2014) 26:289–300. 10.1016/j.clon.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chang CW, Chen YS, Chou SH, Han CL, Chen YJ, Yang CC, et al. Distinct subpopulations of head and neck cancer cells with different levels of intracellular reactive oxygen species exhibit diverse stemness, proliferation, and chemosensitivity. Cancer Res. (2014) 74:6291–305. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Diehn M, Cho RW, Lobo NA, Kalisky T, Dorie MJ, Kulp AN, et al. Association of reactive oxygen species levels and radioresistance in cancer stem cells. Nature. (2009) 458:780–3. 10.1038/nature07733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang M, Liu P, Huang P. Cancer stem cells, metabolism, and therapeutic significance. Tumour Biol. (2016) 37:5735–42. 10.1007/s13277-016-4945-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Szumiel I. Ionizing radiation-induced oxidative stress, epigenetic changes and genomic instability: the pivotal role of mitochondria. Int J Radiat Biol. (2015) 91:1–12. 10.3109/09553002.2014.934929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lagadec C, Dekmezian C, Bauche L, Pajonk F. Oxygen levels do not determine radiation survival of breast cancer stem cells. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e34545 10.1371/journal.pone.0034545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Phillips TM, McBride WH, Pajonk F. The response of CD24(-/low)/CD44+ breast cancer-initiating cells to radiation. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2006) 98:1777–85. 10.1093/jnci/djj495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Al-Assar O, Mantoni T, Lunardi S, Kingham G, Helleday T, Brunner TB. Breast cancer stem-like cells show dominant homologous recombination due to a larger S-G2 fraction. Cancer Biol Ther. (2011) 11:1028–35. 10.4161/cbt.11.12.15699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Abdullah LN, Chow EK. Mechanisms of chemoresistance in cancer stem cells. Clin Transl Med. (2013) 2:3. 10.1186/2001-1326-2-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang ZX, Sun YH, He JG, Cao H, Jiang GQ. Increased activity of CHK enhances the radioresistance of MCF-7 breast cancer stem cells. Oncol Lett. (2015) 10:3443–9. 10.3892/ol.2015.3777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang P, Wei Y, Wang L, Debeb BG, Yuan Y, Zhang J, et al. ATM-mediated stabilization of ZEB1 promotes DNA damage response and radioresistance through CHK1. Nat Cell Biol. (2014) 16:864–75. 10.1038/ncb3013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Desai A, Webb B, Gerson SL. CD133+ cells contribute to radioresistance via altered regulation of DNA repair genes in human lung cancer cells. Radiother Oncol. (2014) 110:538–45. 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.10.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yin H, Glass J. The phenotypic radiation resistance of CD44+/CD24(-or low) breast cancer cells is mediated through the enhanced activation of ATM signaling. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e24080 10.1371/journal.pone.0024080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang WJ, Wu SP, Liu JB, Shi YS, Huang X, Zhang QB, et al. MYC regulation of CHK1 and CHK2 promotes radioresistance in a stem cell-like population of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. (2013) 73:1219–31. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ropolo M, Daga A, Griffero F, Foresta M, Casartelli G, Zunino A, et al. Comparative analysis of DNA repair in stem and nonstem glioma cell cultures. Mol Cancer Res. (2009) 7:383–92. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ahmed SU, Carruthers R, Gilmour L, Yildirim S, Watts C, Chalmers AJ. Selective inhibition of parallel DNA damage response pathways optimizes radiosensitization of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cancer Res. (2015) 75:4416–28. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Carruthers R, Ahmed SU, Strathdee K, Gomez-Roman N, Amoah-Buahin E, Watts C, et al. Abrogation of radioresistance in glioblastoma stem-like cells by inhibition of ATM kinase. Mol Oncol. (2015) 9:192–203. 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cojoc M, Peitzsch C, Kurth I, Trautmann F, Kunz-Schughart LA, Telegeev GD, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase is regulated by β-Catenin/TCF and promotes radioresistance in prostate cancer progenitor cells. Cancer Res. (2015) 75:1482–94. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang X, Ma Z, Xiao Z, Liu H, Dou Z, Feng X, et al. Chk1 knockdown confers radiosensitization in prostate cancer stem cells. Oncol Rep. (2012) 28:2247–54. 10.3892/or.2012.2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mladenov E, Magin S, Soni A, Iliakis G. DNA double-strand-break repair in higher eukaryotes and its role in genomic instability and cancer: cell cycle and proliferation-dependent regulation. Semin Cancer Biol. (2016) 37–38:51–64. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Her J, Bunting SF. How cells ensure correct repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J Biol Chem. (2018) 293:10502–11. 10.1074/jbc.TM118.000371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mao Z, Bozzella M, Seluanov A, Gorbunova V. Comparison of nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination in human cells. DNA Repair. (2008) 7:1765–71. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Skvortsov S, Debbage P, Lukas P, Skvortsova I. Crosstalk between DNA repair and cancer stem cell (CSC) associated intracellular pathways. Semin Cancer Biol. (2015) 31:36–42. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Moore N, Lyle S. Quiescent, slow-cycling stem cell populations in cancer: a review of the evidence and discussion of significance. J Oncol. (2011) 2011:396076. 10.1155/2011/396076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Skvortsova I, Skvortsov S, Stasyk T, Raju U, Popper BA, Schiestl B, et al. Intracellular signaling pathways regulating radioresistance of human prostate carcinoma cells. Proteomics. (2008) 8:4521–33. 10.1002/pmic.200800113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pece S, Tosoni D, Confalonieri S, Mazzarol G, Vecchi M, Ronzoni S, et al. Biological and molecular heterogeneity of breast cancers correlates with their cancer stem cell content. Cell. (2010) 140:62–73. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Touil Y, Igoudjil W, Corvaisier M, Dessein AF, Vandomme J, Monte D, et al. Colon cancer cells escape 5FU chemotherapy-induced cell death by entering stemness and quiescence associated with the c-Yes/YAP axis. Clin Cancer Res. (2014) 20:837–46. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kleffel S, Schatton T. Tumor dormancy and cancer stem cells: two sides of the same coin? Adv Exp Med Biol. (2013) 734:145–79. 10.1007/978-1-4614-1445-2_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li J, Jiang E, Wang X, Shangguan AJ, Zhang L, Yu Z. Dormant cells: the original cause of tumor recurrence and metastasis. Cell Biochem Biophys. (2015) 72:317–20. 10.1007/s12013-014-0477-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lyssiotis CA, Kimmelman AC. Metabolic Interactions in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Cell Biol. (2017) 27:863–75. 10.1016/j.tcb.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Roper J, Yilmaz OH. Metabolic teamwork in the stem cell niche. Cell Metab. (2017) 25:993–4. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Borovski T, De Sousa EMF, Vermeulen L, Medema JP. Cancer stem cell niche: the place to be. Cancer Res. (2011) 71:634–9. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chapellier M, Maguer-Satta V. BMP2, a key to uncover luminal breast cancer origin linked to pollutant effects on epithelial stem cells niche. Mol Cell Oncol. (2016) 3:e1026527. 10.1080/23723556.2015.1026527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Aderetti DA, Hira VVV, Molenaar RJ, van Noorden CJF. The hypoxic peri-arteriolar glioma stem cell niche, an integrated concept of five types of niches in human glioblastoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. (2018) 1869:346–54. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ishii G. Crosstalk between cancer associated fibroblasts and cancer cells in the tumor microenvironment after radiotherapy. EBioMedicine. (2017) 17:7–8. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Tommelein J, De Vlieghere E, Verset L, Melsens E, Leenders J, Descamps B, et al. Radiotherapy-activated cancer-associated fibroblasts promote tumor progression through paracrine IGF1R activation. Cancer Res. (2018) 78:659–70. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Papadopoulou A, Kletsas D. Human lung fibroblasts prematurely senescent after exposure to ionizing radiation enhance the growth of malignant lung epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Int J Oncol. (2011) 39:989–99. 10.3892/ijo.2011.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hawsawi NM, Ghebeh H, Hendrayani SF, Tulbah A, Al-Eid M, Al-Tweigeri T, et al. Breast carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and their counterparts display neoplastic-specific changes. Cancer Res. (2008) 68:2717–25. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang Y, Gan G, Wang B, Wu J, Cao Y, Zhu D, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote irradiated cancer cell recovery through autophagy. EBioMedicine. (2017) 17:45–56. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jarosz-Biej M, Smolarczyk R, Cichon T, Kulach N. Tumor microenvironment as a “game changer” in cancer radiotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20(13). 10.3390/ijms20133212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jiang W, Chan CK, Weissman IL, Kim BYS, Hahn SM. Immune priming of the tumor microenvironment by radiation. Trends Cancer. (2016) 2:638–45. 10.1016/j.trecan.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Matsui WH. Cancer stem cell signaling pathways. Medicine. (2016) 95(1 Suppl. 1):S8–19. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kuonen F, Secondini C, Ruegg C. Molecular pathways: emerging pathways mediating growth, invasion, and metastasis of tumors progressing in an irradiated microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. (2012) 18:5196–202. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sofia Vala I, Martins LR, Imaizumi N, Nunes RJ, Rino J, Kuonen F, et al. Low doses of ionizing radiation promote tumor growth and metastasis by enhancing angiogenesis. PLoS ONE. (2010) 5:e11222. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Elming PB, Sorensen BS, Oei AL, Franken NAP, Crezee J, Overgaard J, et al. Hyperthermia: the optimal treatment to overcome radiation resistant hypoxia. Cancers. (2019) 11:60. 10.3390/cancers11010060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Baumann R, Depping R, Delaperriere M, Dunst J. Targeting hypoxia to overcome radiation resistance in head & neck cancers: real challenge or clinical fairytale? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. (2016) 16:751–8. 10.1080/14737140.2016.1192467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Epel B, Maggio MC, Barth ED, Miller RC, Pelizzari CA, Krzykawska-Serda M, et al. Oxygen-Guided radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2019) 103:977–84. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.10.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gallez B, Neveu MA, Danhier P, Jordan BF. Manipulation of tumor oxygenation and radiosensitivity through modification of cell respiration. A critical review of approaches and imaging biomarkers for therapeutic guidance. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. (2017) 1858:700–11. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Horsman MR, Overgaard J. The impact of hypoxia and its modification of the outcome of radiotherapy. J Radiat Res. (2016) 57(Suppl. 1):i90-i8. 10.1093/jrr/rrw007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Eisenbrey JR, Shraim R, Liu JB, Li J, Stanczak M, Oeffinger B, et al. Sensitization of hypoxic tumors to radiation therapy using ultrasound-sensitive oxygen microbubbles. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2018) 101:88–96. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.01.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Schulz A, Meyer F, Dubrovska A, Borgmann K. Cancer stem cells and radioresistance: DNA repair and beyond. Cancers. (2019) 11:862. 10.3390/cancers11060862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Krause M, Dubrovska A, Linge A, Baumann M. Cancer stem cells: radioresistance, prediction of radiotherapy outcome and specific targets for combined treatments. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. (2017) 109:63–73. 10.1016/j.addr.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Schoning JP, Monteiro M, Gu W. Drug resistance and cancer stem cells: the shared but distinct roles of hypoxia-inducible factors HIF1α and HIF2α. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. (2017) 44:153–61. 10.1111/1440-1681.12693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Balamurugan K. HIF-1 at the crossroads of hypoxia, inflammation, and cancer. Int J Cancer. (2016) 138:1058–66. 10.1002/ijc.29519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Peitzsch C, Perrin R, Hill RP, Dubrovska A, Kurth I. Hypoxia as a biomarker for radioresistant cancer stem cells. Int J Radiat Biol. (2014) 90:636–52. 10.3109/09553002.2014.916841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kim W, Kim MS, Kim HJ, Lee E, Jeong JH, Park I, et al. Role of HIF-1α in response of tumors to a combination of hyperthermia and radiation in vivo. Int J Hyperthermia. (2018) 34:276–83. 10.1080/02656736.2017.1335440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Nwabo Kamdje AH, Takam Kamga P, Tagne Simo R, Vecchio L, Seke Etet PF, Muller JM, et al. Developmental pathways associated with cancer metastasis: Notch, Wnt, and Hedgehog. Cancer Biol Med. (2017) 14:109–20. 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2016.0032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chatterjee S, Sil PC. Targeting the crosstalks of Wnt pathway with Hedgehog and Notch for cancer therapy. Pharmacol Res. (2019) 142:251–61. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Qiang L, Wu T, Zhang HW, Lu N, Hu R, Wang YJ, et al. HIF-1α is critical for hypoxia-mediated maintenance of glioblastoma stem cells by activating Notch signaling pathway. Cell Death Differ. (2012) 19:284–94. 10.1038/cdd.2011.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wang J, Wakeman TP, Lathia JD, Hjelmeland AB, Wang XF, White RR, et al. Notch promotes radioresistance of glioma stem cells. Stem Cells. (2010) 28:17–28. 10.1002/stem.261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Duru N, Fan M, Candas D, Menaa C, Liu HC, Nantajit D, et al. HER2-associated radioresistance of breast cancer stem cells isolated from HER2-negative breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. (2012) 18:6634–47. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Woodward WA, Chen MS, Behbod F, Alfaro MP, Buchholz TA, Rosen JM. WNT/β-catenin mediates radiation resistance of mouse mammary progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2007) 104:618–23. 10.1073/pnas.0606599104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Oren O, Smith BD. Eliminating cancer stem cells by targeting embryonic signaling pathways. Stem Cell Rev Rep. (2017) 13:17–23. 10.1007/s12015-016-9691-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Wu CT, Lin WY, Chang YH, Chen WC, Chen MF. Impact of CD44 expression on radiation response for bladder cancer. J Cancer. (2017) 8:1137–44. 10.7150/jca.18297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Hagiwara M, Kikuchi E, Kosaka T, Mikami S, Saya H, Oya M. Variant isoforms of CD44 expression in upper tract urothelial cancer as a predictive marker for recurrence and mortality. Urol Oncol. (2016) 34:337.e19–26. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Yikilmaz TN, Dirim A, Ayva ES, Ozdemir H, Ozkardes H. Clinical use of tumor markers for the detection and prognosis of bladder carcinoma: a comparison of CD44, Cytokeratin 20 and Survivin. Urol J. (2016) 13:2677–83. 10.22037/uj.v13i3.3294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Szczepanik A, Sierzega M, Drabik G, Pituch-Noworolska A, Kolodziejczyk P, Zembala M. CD44(+) cytokeratin-positive tumor cells in blood and bone marrow are associated with poor prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. (2019) 22:264–72. 10.1007/s10120-018-0858-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Watanabe T, Okumura T, Hirano K, Yamaguchi T, Sekine S, Nagata T, et al. Circulating tumor cells expressing cancer stem cell marker CD44 as a diagnostic biomarker in patients with gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. (2017) 13:281–8. 10.3892/ol.2016.5432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Kodama H, Murata S, Ishida M, Yamamoto H, Yamaguchi T, Kaida S, et al. Prognostic impact of CD44-positive cancer stem-like cells at the invasive front of gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. (2017) 116:186–94. 10.1038/bjc.2016.401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Fang M, Wu J, Lai X, Ai H, Tao Y, Zhu B, et al. CD44 and CD44v6 are correlated with gastric cancer progression and poor patient prognosis: evidence from 42 Studies. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2016) 40:567–78. 10.1159/000452570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bitaraf SM, Mahmoudian RA, Abbaszadegan M, Mohseni Meybodi A, Taghehchian N, Mansouri A, et al. Association of Two CD44 Polymorphisms with clinical outcomes of gastric cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2018) 19:1313–8. 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.5.1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Hsu CP, Lee LY, Hsu JT, Hsu YP, Wu YT, Wang SY, et al. CD44 Predicts early recurrence in pancreatic cancer patients undergoing radical surgery. In vivo. (2018) 32:1533–40. 10.21873/invivo.11411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Poruk KE, Blackford AL, Weiss MJ, Cameron JL, He J, Goggins M, et al. Circulating tumor cells expressing markers of tumor-initiating cells predict poor survival and cancer recurrence in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. (2017) 23:2681–90. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Ludwig N, Szczepanski MJ, Gluszko A, Szafarowski T, Azambuja JH, Dolg L, et al. CD44(+) tumor cells promote early angiogenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. (2019) 467:85–95. 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Rodrigues M, Xavier FCA, Andrade NP, Lopes C, Miguita Luiz L, Sedassari BT, et al. Prognostic implications of CD44, NANOG, OCT4, and BMI1 expression in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. (2018) 40:1759–73. 10.1002/hed.25158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Lee JR, Roh JL, Lee SM, Park Y, Cho KJ, Choi SH, et al. Overexpression of cysteine-glutamate transporter and CD44 for prediction of recurrence and survival in patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. (2018) 40:2340–6. 10.1002/hed.25331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Hou C, Ishi Y, Motegi H, Okamoto M, Ou Y, Chen J, et al. Overexpression of CD44 is associated with a poor prognosis in grade II/III gliomas. J Neurooncol. (2019) 145:201–10. 10.1007/s11060-019-03288-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Nishikawa M, Inoue A, Ohnishi T, Kohno S, Ohue S, Matsumoto S, et al. Significance of glioma stem-like cells in the tumor periphery that express high levels of CD44 in tumor invasion, early progression, and poor prognosis in glioblastoma. Stem Cells Int. (2018) 2018:5387041. 10.1155/2018/5387041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Liu WH, Lin JC, Chou YC, Li MH, Tsai JT. CD44-associated radioresistance of glioblastoma in irradiated brain areas with optimal tumor coverage. Cancer Med. (2020) 9:350–60. 10.1002/cam4.2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Mooney KL, Choy W, Sidhu S, Pelargos P, Bui TT, Voth B, et al. The role of CD44 in glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Neurosci. (2016) 34:1–5. 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Bi Y, Meng Y, Wu H, Cui Q, Luo Y, Xue X. Expression of the potential cancer stem cell markers CD133 and CD44 in medullary thyroid carcinoma: a ten-year follow-up and prognostic analysis. J Surg Oncol. (2016) 113:144–51. 10.1002/jso.24124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Han SA, Jang JH, Won KY, Lim SJ, Song JY. Prognostic value of putative cancer stem cell markers (CD24, CD44, CD133, and ALDH1) in human papillary thyroid carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. (2017) 213:956–63. 10.1016/j.prp.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Luo Y, Tan Y. Prognostic value of CD44 expression in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. (2016) 16:47. 10.1186/s12935-016-0325-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Zhao Q, Zhou H, Liu Q, Cao Y, Wang G, Hu A, et al. Prognostic value of the expression of cancer stem cell-related markers CD133 and CD44 in hepatocellular carcinoma: from patients to patient-derived tumor xenograft models. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:47431–43. 10.18632/oncotarget.10164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Xu H, Tian Y, Yuan X, Liu Y, Wu H, Liu Q, et al. Enrichment of CD44 in basal-type breast cancer correlates with EMT, cancer stem cell gene profile, and prognosis. Onco Targets Ther. (2016) 9:431–44. 10.2147/OTT.S97192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Hu B, Ma Y, Yang Y, Zhang L, Han H, Chen J. CD44 promotes cell proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. (2018) 15:5627–33. 10.3892/ol.2018.8051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Sosulski A, Horn H, Zhang L, Coletti C, Vathipadiekal V, Castro CM, et al. CD44 Splice Variant v8–10 as a marker of serous ovarian cancer prognosis. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0156595. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Lin J, Ding D. The prognostic role of the cancer stem cell marker CD44 in ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. (2017) 17:8. 10.1186/s12935-016-0376-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Matuura H, Miyamoto M, Takano M, Soyama H, Aoyama T, Yoshikawa T, et al. Low Expression of CD44 is an independent factor of poor prognosis in ovarian mucinous carcinoma. Anticancer Res. (2018) 38:717–22. 10.21873/anticanres.12277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Horimoto Y, Arakawa A, Sasahara N, Tanabe M, Sai S, Himuro T, et al. Combination of cancer stem cell markers CD44 and CD24 is superior to ALDH1 as a prognostic indicator in breast cancer patients with distant metastases. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0165253. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Han S, Huang T, Li W, Wang X, Wu X, Liu S, et al. Prognostic value of CD44 and its isoforms in advanced cancer: a systematic meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Front Oncol. (2019) 9:39. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Linge A, Lohaus F, Lock S, Nowak A, Gudziol V, Valentini C, et al. HPV status, cancer stem cell marker expression, hypoxia gene signatures and tumour volume identify good prognosis subgroups in patients with HNSCC after primary radiochemotherapy: a multicentre retrospective study of the German Cancer Consortium Radiation Oncology Group (DKTK-ROG). Radiother Oncol. (2016) 121:364–73. 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Linge A, Lock S, Gudziol V, Nowak A, Lohaus F, von Neubeck C, et al. Low cancer stem cell marker expression and low hypoxia identify good prognosis subgroups in HPV(-) HNSCC after postoperative radiochemotherapy: a multicenter study of the DKTK-ROG. Clin Cancer Res. (2016) 22:2639–49. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Linge A, Schmidt S, Lohaus F, Krenn C, Bandurska-Luque A, Platzek I, et al. Independent validation of tumour volume, cancer stem cell markers and hypoxia-associated gene expressions for HNSCC after primary radiochemotherapy. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. (2019) 16:40–7. 10.1016/j.ctro.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Dong BW, Qin GM, Luo Y, Mao JS. Metabolic enzymes: key modulators of functionality in cancer stem-like cells. Oncotarget. (2017) 8:14251–67. 10.18632/oncotarget.14041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Voutsadakis IA. Proteasome expression and activity in cancer and cancer stem cells. Tumour Biol. (2017) 39:1010428317692248. 10.1177/1010428317692248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Banno A, Garcia DA, van Baarsel ED, Metz PJ, Fisch K, Widjaja CE, et al. Downregulation of 26S proteasome catalytic activity promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:21527–41. 10.18632/oncotarget.7596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177.Lenos KJ, Vermeulen L. Cancer stem cells don't waste their time cleaning-low proteasome activity, a marker for cancer stem cell function. Ann Transl Med. (2016) 4:519. 10.21037/atm.2016.11.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178.Lagadec C, Vlashi E, Bhuta S, Lai C, Mischel P, Werner M, et al. Tumor cells with low proteasome subunit expression predict overall survival in head and neck cancer patients. BMC Cancer. (2014) 14:152. 10.1186/1471-2407-14-152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 179.Han M, Guo L, Zhang Y, Huang B, Chen A, Chen W, et al. Clinicopathological and Prognostic Significance of CD133 in glioma patients: a meta-analysis. Mol Neurobiol. (2016) 53:720–7. 10.1007/s12035-014-9018-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 180.Li B, McCrudden CM, Yuen HF, Xi X, Lyu P, Chan KW, et al. CD133 in brain tumor: the prognostic factor. Oncotarget. (2017) 8:11144–59. 10.18632/oncotarget.14406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 181.Wu X, Wu F, Xu D, Zhang T. Prognostic significance of stem cell marker CD133 determined by promoter methylation but not by immunohistochemical expression in malignant gliomas. J Neurooncol. (2016) 127:221–32. 10.1007/s11060-015-2039-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 182.Kim KJ, Lee KH, Kim HS, Moon KS, Jung TY, Jung S, et al. The presence of stem cell marker-expressing cells is not prognostically significant in glioblastomas. Neuropathology. (2011) 31:494–502. 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2010.01194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]