Using Surveillance With Near–Real-Time Alerts During a Cluster of Overdoses From Fentanyl-Contaminated Crack Cocaine, Connecticut, June 2019 (original) (raw)

Abstract

In 2019, Connecticut launched an opioid overdose–monitoring program to provide rapid intervention and limit opioid overdose–related harms. The Connecticut Statewide Opioid Response Directive (SWORD)—a collaboration among the Connecticut State Department of Public Health, Connecticut Poison Control Center (CPCC), emergency medical services (EMS), New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA), and local harm reduction groups—required EMS providers to call in all suspected opioid overdoses to the CPCC. A centralized data collection system and the HIDTA overdose mapping tool were used to identify outbreaks and direct interventions. We describe the successful identification of a cluster of fentanyl-contaminated crack cocaine overdoses leading to a rapid public health response. On June 1, 2019, paramedics called in to the CPCC 2 people with suspected opioid overdose who reported exclusive use of crack cocaine after being resuscitated with naloxone. When CPCC specialists in poison information followed up on the patients’ status with the emergency department, they learned of 2 similar cases, raising suspicion that a batch of crack cocaine was mixed with an opioid, possibly fentanyl. The overdose mapping tool pinpointed the overdose nexus to a neighborhood in Hartford, Connecticut; the CPCC supervisor alerted the Connecticut State Department of Public Health, which in turn notified local health departments, public safety officials, and harm reduction groups. Harm reduction groups distributed fentanyl test strips and naloxone to crack cocaine users and warned them of the dangers of using alone. The outbreak lasted 5 days and tallied at least 22 overdoses, including 6 deaths. SWORD’s near–real-time EMS reporting combined with the overdose mapping tool enabled rapid recognition of this overdose cluster, and the public health response likely prevented additional overdoses and loss of life.

Keywords: opioid overdose, public health surveillance

With a 2019 estimated population of 3 565 300, Connecticut is the third smallest state by land mass but the fourth most densely populated state. 1,2 It is served by 398 emergency medical services (EMS) agencies (including volunteer and first responders) and 27 acute care hospitals. In 2018, state EMS responded to 688 937 calls (written communication, Raffaella Coler, MEd, RN, Office of Emergency Medical Services, Connecticut State Department of Public Health [CT DPH], October 2020). Connecticut is one of the top 10 states in age-adjusted heroin and fentanyl overdose death rates. 3

In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention gave the state funds to enhance the data collection of fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses as part of the Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance (ESOOS) program. 4 In 2018, Connecticut enacted a law mandating the reporting of all opioid overdoses to CT DPH, which went into effect in 2019. 5 Based on the successful implementation of a pilot program in Hartford, Connecticut, 6 CT DPH launched the Statewide Opioid Response Directive (SWORD) program to fulfill the reporting mandate. SWORD was a collaboration among CT DPH, the Connecticut Poison Control Center (CPCC), EMS, the New England High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (HIDTA), and community-based harm reduction groups that mandated EMS providers call in each suspected opioid overdose to CPCC specialists in poison information (hereinafter, CPCC specialists). The HIDTA program provides federal drug prevention and law enforcement aid to state and local agencies in major drug-trafficking areas. CPCC is protected by a waiver under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), enabling health professionals to confidentially share patient information. 7 Once the overdose data collection was completed in the CPCC electronic record, CPCC specialists entered relevant data into the HIDTA overdose mapping tool (Overdose Mapping Application Program [ODMAP]), a web-based interactive map that uses global positioning system software to plot each overdose as a colored dot on a map (http://www.odmap.org). ODMAP also provides analytics to identify overdose clusters over time. ODMAP can be accessed after obtaining user permissions from HIDTA.

Although the Maryland Poison Center had previously collected layperson reports of naloxone administration, the Connecticut SWORD program was the first statewide mandated reporting of opioid overdoses by EMS to a poison center. 8 We describe the successful identification of a cluster of overdoses by SWORD and ODMAP leading to a rapid public health response.

Methods

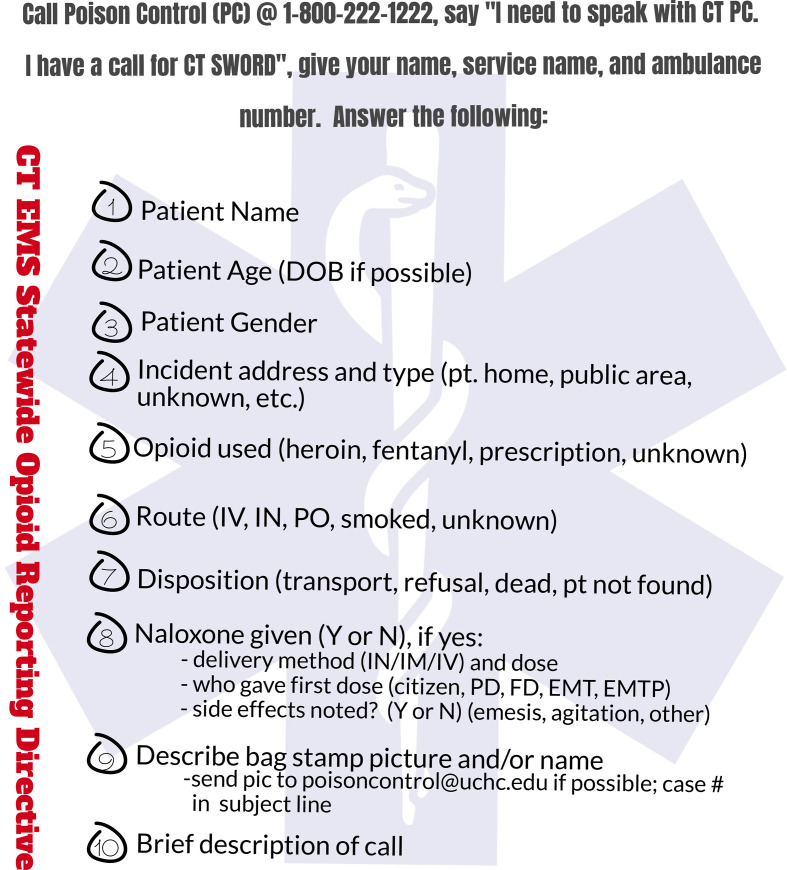

In June 2019, CT DPH launched the SWORD program statewide. The SWORD program mandated all EMS responders in Connecticut to (1) call CPCC for every suspected opioid overdose, (2) call as close to the time of dispatch as possible, (3) answer 10 questions about the basic details of the incident (Figure 1), and (4) give a brief report on the circumstances surrounding the incident (ie, a narrative). After receiving the EMS call, CPCC specialists created a record in the poison center electronic database. CPCC specialists entered the following information from each case into ODMAP: address (converted to global positioning satellite coordinates), age, sex, transportation to hospital (yes/no), number of naloxone doses (1, ≥2), who administered the naloxone (bystander, police officer, firefighter, or EMS personnel), and outcome (fatal or nonfatal). The average call duration from an EMS responder was 3 minutes.

Figure 1.

Question card for the Connecticut Statewide Opioid Response Directive (SWORD) emergency medical services (EMS). EMS responders use the card when reporting overdoses to the Connecticut Poison Control Center. Abbreviations: CT, Connecticut; DOB, date of birth; EMT, emergency medical technician; EMTP, emergency medical technician–paramedic; FD, fire department; IM, intramuscular; IN, intranasal; IV, intravenous; PD, police department; PO, by mouth; PT, patient.

EMS responders watched training videos describing the project and received pocket cards that included the CPCC telephone number and 10 questions to be asked (Figure 1). CPCC specialists participated in training sessions conducted by the CPCC manager, who also supervised initial case entries into ODMAP. CT DPH published quarterly reports and monthly newsletters to reinforce the importance of SWORD and the need for full and timely reporting.

State epidemiologists conducted surveillance through regular review of the database using ODMAP analytic tools, including maps and spreadsheets. In ODMAP, each overdose is represented as a color- and shape-coded dot on the ODMAP. Hovering over a dot reveals details about the overdose. ODMAP shows the general area where an overdose has occurred without specifying the street address. Three state attorneys general have ruled ODMAP does not violate HIPAA privacy rules. 9

ODMAP can be queried on demand or can be set to run at regular intervals. ODMAP queries can include data on time parameters, county, and zip code. Public health and law enforcement officials can query ODMAP to identify areas where they can best deploy resources to address crises and conduct outreach.

By specifying volume thresholds for different areas, ODMAP can send email alerts to authorized organizations. If the number of overdoses in a county meets or exceeds the predetermined threshold for a 24-hour period, emails (also called “spike alerts”) are immediately sent to a programmable list of recipients, such as local health departments and districts, ambulance companies, law enforcement officials, fire departments, and harm reduction groups.

After being notified of a spike alert, state epidemiologists and analysts review the data input into ODMAP and the case narratives in the CPCC database. Then they can contact the Connecticut Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for detailed information on new fatal overdose cases and review the state’s EpiCenter syndromic surveillance system, which provides near–real-time estimates of emergency department (ED) use for nonfatal and fatal suspected drug and opioid overdoses. Analyses and interpretation of all databases are shared with local health department and public safety officials when a public health threat is determined.

CPCC, using its staff knowledge of illicit drug markets, pharmacology, and pharmacokinetics, also monitors calls for unusual cases or small clusters of cases that do not meet the ODMAP volume thresholds and immediately notifies state epidemiologists on discovery.

Outcomes

On June 1, 2019, 2 people at a residence in Hartford smoked crack cocaine. Both people became immediately unresponsive, and a third person called 911. EMS responders recognized the opioid toxidrome of miosis (pinpoint pupils), lethargy, and depressed respirations. They provided rescue breathing and administered naloxone. Both patients responded to the naloxone, reported smoking crack cocaine only, and denied the use of opioids. Neither developed opioid withdrawal. The paramedics transported them to the ED and reported the double overdose to CPCC by telephone.

This report was the third overdose CPCC specialists had received from the same Hartford area that morning. When CPCC specialists contacted the ED to conduct routine follow-up on the double overdose patients, the ED nurse mentioned the arrival of 2 additional patients with similar presentations not yet reported to CPCC. ODMAP revealed that 5 overdoses were largely confined to a small Hartford neighborhood. CPCC specialists alerted their supervisor, who then alerted the on-call state epidemiologist that a possible outbreak of fentanyl-contaminated crack cocaine had been identified in Hartford.

On the first day of the cluster, CPCC received 13 reports of overdose from EMS responders. Although 6 patients denied using drugs, all presented with opioid toxidrome and all responded to naloxone. Six reported using crack cocaine only, and 1 patient who denied drug use tested positive for both cocaine and fentanyl via a urine sample. Several patients left the hospital before being tested. ODMAP showed that most of the overdoses were located in or linked to a small section of Hartford. CT DPH and CPCC staff members notified the Hartford Police Department, Hartford Department of Health and Human Services, local harm reduction groups, and the state’s HIDTA health analyst of the events.

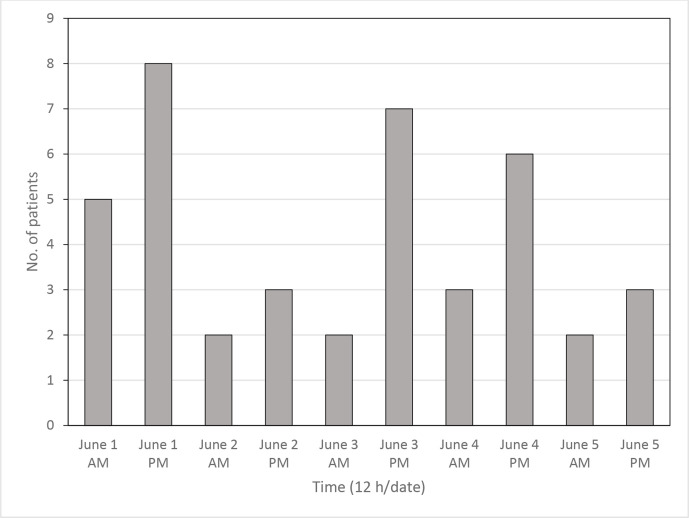

During the next few days, CPCC received 8 reports from EMS responders of similar overdoses inside and outside Hartford city limits. On June 5, 2 decedents were discovered near the original implicated area, including 1 decedent who had likely been dead for several days and was, according to the EMS case narrative recorded by CPCC, “laying on his back, crack pipe in hands.” During the 5-day outbreak, CPCC received reports of 41 opioid overdoses from EMS responders (Figure 2). State epidemiologists reviewed data from SWORD, EpiCenter, and the chief medical examiner’s office and concluded that the fentanyl/cocaine cluster included at least 22 overdoses, with 6 fatalities. A drug sample seized from one of the double overdose scenes tested positive for both fentanyl and cocaine at the Connecticut State Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection Division of Scientific Services laboratory using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. The median age of the cluster of patients was 50, and 18 patients were men. All 6 fatalities tested positive for fentanyl and cocaine in postmortem blood testing conducted at the National Medical Services Labs.

Figure 2.

Number of emergency medical services–suspected opioid overdoses called into the Connecticut Poison Control Center, by time of call, Hartford, Connecticut, June 1-5, 2019.

CT DPH provided extra state-funded fentanyl test strips to the Greater Hartford Harm Reduction Coalition (GHHRC). GHHRC providers distributed more than 300 fentanyl test strips and 125 naloxone kits during 5 days and provided education to 64 opioid-naïve crack cocaine users within or close to the hotspot. Harm reduction workers identified a possible source of contaminated drugs and warned users to be cautious. Police made drug arrests in the area but were unable to catch a dealer with contaminated product. Once the cluster ended on the fifth day, no additional reports of similar overdoses occurred in Hartford until several weeks later, when a single case was reported.

Lessons Learned

Outbreaks of opioid-contaminated crack cocaine have become more frequent. In 2016 in Vancouver, British Columbia, a 4-day outbreak of crack cocaine/furanyl fentanyl exposures was identified that resulted in 43 overdoses and 1 death. 10 In 2018, another 4-day cluster of crack cocaine/fentanyl exposures in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, resulted in 16 overdoses and 3 deaths. 11 These outbreaks were identified by observer reports of single unexpected presentations. Alternatively, the SWORD program is designed to rapidly identify outbreaks 24/7 using technology and analytical tools.

SWORD identified this outbreak in just 4 hours. In most states that use ODMAP, data entry is performed by thousands of EMS providers or by computer-to-computer information exchange. The SWORD program’s centralized data input using CPCC specialists with expertise in poisoning assessment, toxicology, and data collection, as well as the EMS narratives providing key details of the overdose, enabled rapid identification of these cases.

The SWORD program is unique for several reasons. First, statewide reporting of opioid overdoses by EMS to CPCC had not previously been mandated. This mandate proved to be essential to the rapid identification of the first few cases. Second, the SWORD program, through ODMAP, pinpointed the problem at the street level. Many geocoding programs rely on ZIP code for geographic distribution. ZIP codes, on average, cover 90 square miles—areas that are too large to effectively monitor for outbreaks of 20-40 overdoses. Third, the SWORD program disseminated information quickly, because its interactive maps are displayed on the internet and, therefore, are immediately available to state and local public health and safety groups. It also disseminated information quickly and systematically via email distribution lists. The SWORD program’s precise geocoding and visual display quickly identified the nexus of the cluster, enabling a public health response in a specific neighborhood.

To track the opioid epidemic, some states use medical examiner data, which are delayed, or track naloxone administration, which is not a reliable surrogate for overdose because some EMS responders administer naloxone for coma of unknown etiology and some opioid overdoses do not require naloxone. 12 The SWORD program’s strength is EMS identification of patients with suspected opioid overdoses whether or not naloxone was administered. The EMS narratives provide verification of paraphernalia, patient and bystander statements of drug use, and response to naloxone administration.

Three hundred thirty-one spike alerts were issued in the program’s first year. In this outbreak of fentanyl-contaminated crack cocaine, because identification of the first 4 cases was made by CPCC specialists, CPCC telephoned the on-call epidemiologist and sent a separate email to state and local partners, including harm reduction groups, with details outlining the threat posed, enabling a rapid, community-focused response to the threat.

GHHRC played a critical role in the response to this outbreak. GHHRC providers, armed with information from SWORD/ODMAP, immediately reached out to traditionally hard-to-reach populations at risk of overdose (ie, crack cocaine users) on the street, alerting them to possible opioid contamination of crack cocaine being sold in the neighborhood. They provided fentanyl test strips, distributed naloxone, and educated crack cocaine users on the need to use with a partner and call 911 should an overdose occur. We believe these efforts limited the number of deaths because many of the people who used crack cocaine were unaware of the dangerous opioid/crack combination leading to an increase in the number of overdoses. As an added benefit, people using crack cocaine sought increased services from GHHRC after this outreach.

Our novel model is broadly applicable to other states and territories because all states and territories are covered by a poison control center. A SWORD model can be implemented at the city level, as it was in our original pilot project, or at the county or state level depending on an area’s resources. Implementation of a similar program may require additional staffing and training. Previously, EMS providers did not call CPCC for overdoses; as such, the SWORD project imposed on them a different work flow. From the beginning of the program, EMS responders and CPCC specialists strived to minimize delays in reporting. In a survey of 48 EMS responders who participated in the pilot program, 44 (92%) were clear on what they needed to report, and 40 (84%) found the amount of information to report was reasonable. 13 The median time from EMS dispatch to reporting to CPCC was 61 minutes (range, 17-298 minutes). CPCC increased staffing and modified shifts to accommodate the increase in telephone traffic. The average time CPCC specialists spent entering a new case into ODMAP was 2 minutes.

Despite the challenge, EMS compliance was 70%-80% and continued to improve. 14 During the first year of the program, CPCC received 4545 SWORD overdose reports from EMS responders, a 15% annual increase in call volume to the poison center compared with the previous 12-month period (written communication, Katherine Hart, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, CPCC, UConn Health, October 2020). Implementation also requires ODMAP training, quality assurance systems, and a good working relationship with the public health department and other partners.

One limitation of the SWORD program is that it undercounts fatal overdoses. Only 3 of the 6 fatalities from this cluster were reported by EMS providers; the other 3 were identified by the medical examiner’s office. People who were found dead with no visible paraphernalia and no witnesses may not meet the criteria for suspected opioid overdose and may not be reported to CPCC. Another limitation of the SWORD program is that data depend on adherence to the program from EMS providers and CPCC specialists. Sustained engagement from these groups is essential. In the future, we hope to further improve EMS compliance through additional training and feedback, develop opioid death alerts, further develop spike alert response plans with localities, use an applied programming interface to populate ODMAP automatically, have ODMAPs displayed in EMS base stations and EDs, and expand overdose reporting to drug categories beyond opioids.

States hoping to enhance tracking of the opioid overdose epidemic and speed up the identification of threats should consider adapting Connecticut’s surveillance system. In particular, they should consider near–real-time EMS reporting through their poison control centers as in our SWORD model. This model shows that robust public health surveillance of ongoing systematic data collection, analysis, and interpretation can be used to identify opioid overdose clusters and inform public health responses, ultimately saving lives.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the hard work and dedication of the state’s EMS responders and CPCC call specialists, who were vital to the SWORD program’s success, and the frontline harm reduction workers who are often underrecognized for their crucial role in battling the overdose death epidemic.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Peter Canning, Mr.RN https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5929-9997

References

- 1.US Census Bureau . QuickFacts: Connecticut. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/CT

- 2.US Census Bureau . United States Summary: 2010—Population and Housing Unit Counts: 2010 Census of Population and Housing. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration; 2012. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/cph-2-1.pdf

- 3.US Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration . 2018 National Drug Threat Assessment. DEA-DCT-DIR-032-18. US Department of Justice; October 2018. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-11/DIR-032-18 2018 NDTA %5Bfinal%5D low resolution11-20.pdf

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Opioid overdose: Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance (ESOOS). Accessed May 27, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/foa/state-opioid-mm.html

- 5.Conn Gen Stat Volume 6, Title 19a, Ch 368a, § 19a-127q.

- 6.Canning P., McKay C., Doyon S., Laska E., Hart K., Kamin R. Coordinated surveillance of opioid overdoses in Hartford, Connecticut: a pilot project. Connecticut Med. 2019;83(6):293-299. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information . Fed Reg. 2001;65(250):16. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/133026/PvcFR04_1.pdf [PubMed]

- 8.Doyon S., Benton C., Anderson BA. et al. Incorporation of poison center services in a state-wide overdose education and naloxone distribution program. Am J Addict. 2016;25(4):301-306. 10.1111/ajad.12384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association . ODMAP and protected health information under HIPAA: guidance document. 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020. http://www.odmap.org/Content/docs/training/featured/ODMAP-Data-Privacy-Guidance-Document.pdf

- 10.Klar SA., Brodkin E., Gibson E. et al. Notes from the field: furanyl-fentanyl overdose events caused by smoking contaminated crack cocaine—British Columbia, Canada, July 15-18, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(37):1015-1016. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6537a6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khatri UG., Viner K., Perrone J. Lethal fentanyl and cocaine intoxication. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(18):1782. 10.1056/NEJMc1809521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grover JM., Alabdrabalnabi T., Patel MD. et al. Measuring a crisis: questioning the use of naloxone administrations as a marker for opioid overdoses in a large U.S. EMS system. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(3):281-289. 10.1080/10903127.2017.1387628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanoian A. Hartford Opioid Project Marketing Analysis Report. Connecticut Poison Control Center; January 2019.

- 14.Connecticut Department of Public Health. Office of Emergency Medical Services . Statewide Opioid Reporting Directive (SWORD) 2020 Annual Report. Connecticut Department of Public Health; 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020. https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/Departments-and-Agencies/DPH/dph/ems/pdf/SWORD/SWORD-newsletters/2020/20200812-SWORD-Annual-ReportFINAL.pdf