Unusual causes for meralgia paresthetica: systematic review of the literature and single center experience (original) (raw)

Abstract

Meralgia paresthetica is often idiopathic, but sometimes symptoms may be caused by traumatic injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) or compression of this nerve by a mass lesion. In this article the literature is reviewed on unusual causes for meralgia paresthetica, including different types of traumatic injury and compression of the LFCN by mass lesions. In addition, the experience from our center with the surgical treatment of unusual causes of meralgia paresthetica is presented. A PubMed search was performed on unusual causes for meralgia paresthetica. Specific attention was paid to factors that may have predisposed to LFCN injury and clues that may have pointed at a mass lesion. Moreover, our own database on all surgically treated cases of meralgia paresthetica between April 2014 and September 2022 was reviewed to identify unusual causes for meralgia paresthetica. A total of 66 articles was identified that reported results on unusual causes for meralgia paresthetica: 37 on traumatic injuries of the LFCN and 29 on compression of the LFCN by mass lesions. Most frequent cause of traumatic injury in the literature was iatrogenic, including different procedures around the anterior superior iliac spine, intra-abdominal procedures and positioning for surgery. In our own surgical database of 187 cases, there were 14 cases of traumatic LFCN injury and 4 cases in which symptoms were related to a mass lesion. It is important to consider traumatic causes or compression by a mass lesion in patients that present with meralgia paresthetica.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10143-023-02023-2.

Keywords: Trauma, Traumatic, Mass lesion, Schwannoma, Lipoma, Endometriosis

Introduction

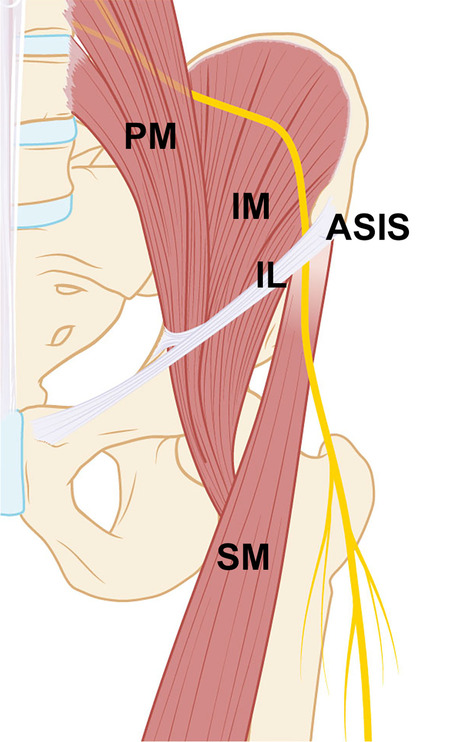

Meralgia paresthetica is a mononeuropathy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN). The LFCN is a pure sensory nerve that is formed by the roots L2 and L3 (Fig. 1). In the retroperitoneal space the nerve runs posterior to the psoas muscle in a caudolateral direction and more distally runs on top of the iliac muscle. It frequently exits the pelvis just medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) under the inguinal ligament, but anatomical variations have been described, where the nerve runs lateral to the ASIS or has a more medial course [1]. In thigh the LFCN runs on top of the sartorius muscle, and distally it pierces the fascia lata and splits into multiple branches that innervate the skin. The LFCN is a pure sensory nerve. Patients with meralgia paresthetica often experience a tingling or burning sensation in the anterolateral part of the thigh. Pressure on the skin may sometimes exacerbate symptoms (dysesthesia).

Fig. 1.

Anatomical drawing of the course of the LFCN: The nerve originates from the nerve roots L2 and L3 runs posterior to the psoas muscle (PM) in the retroperitoneal space on top of the iliac muscle (IM) and exits the pelvis through the inguinal ligament (IL), just medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), and in the upper leg runs on top of the sartorius muscles (SM). This anatomical drawing shows the type B variant, which is most frequently encountered in patients with idiopathic meralgia paresthetica [78]

The term meralgia paresthetica in the literature is often used for idiopathic cases, in which there is no clear cause for the symptoms. It is questionable however if the term ‘idiopathic’ can be applied in meralgia paresthetica, because intra-operatively often a clear site of entrapment is found at the site where the LFCN pierces the inguinal ligament. Moreover, meralgia paresthetica has been reported to be associated with overweight, and sometimes symptoms have been reported to occur after strenuous exercise [2], accidents (seat-belt injury due to a car accident) [3] or positioning for surgery such as prone positioning for spine surgery [4]. In addition, meralgia paresthetica may be the result of iatrogenic injury to the LFCN, caused by surgical procedures around the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), including the anterior approach for placement of hip prosthesis [5], the ilioinguinal approach for acetabular fractures [6], the harvest of iliac bone graft [7, 8] and inguinal hernia repair [9]. Moreover, several case reports have been published on unusual causes of traumatic injury and compression of the LFCN by mass lesions.

The goal of this study was to review the literature on unusual causes of meralgia paresthetica and investigate our own experience with the treatment of these cases from our surgical database.

Material and methods

Literature review

On September 7, 2022 a Pubmed search was performed using the search strategy provided in Appendix. Abstract was reviewed for unusual causes of meralgia paresthetica including traumatic injury and potential compression by a mass lesion. All selected articles were read by the first (GdR) and senior author (AK). Only articles in which the mechanism of injury or cause for compression for the cases was described were used for this review, and case series without description of the individual cases were excluded. In addition, case reports that were published in Journals that could not be accessed were excluded (a PRISMA Flow Diagram is provided in Appendix). The included cases were screened for factors that might have predisposed to the LFCN injury. Remarks were made on potential pathophysiologic mechanisms, onset of symptoms, additional work-up that was performed, intra-operative findings and anatomic variation in the course of the LFCN. For the latter we used the classification introduced by Aszmann et al. [1] that describes the course of the LFCN in relation to the ASIS in a coronal plane: type A: LFCN course lateral to the ASIS, type B and C: just medial to the ASIS (type C: between a split tendon of the sartorius muscle) type D: 1–3 cm medial to the ASIS and type E >3cm medial to the ASIS. For mass lesions, all potential clues that might have pointed to an unusual cause were noted.

Review of surgical series

Before start of the study, approval was obtained from the Medical Ethical Committee of our hospital to review the surgical database on meralgia paresthetica. A total of 187 cases were identified that had been operated in our Center between April 1, 2014 and September 1, 2022. All cases with potential traumatic injury to the LFCN or compression by a mass lesion were selected for review. Medical records were reviewed for cause of injury or compression by mass lesion. Results of surgical treatment were evaluated retrospectively. Remarks were made on the description of symptoms, interval between trauma and presentation, additional work-up and presence of anatomical variation in the course of the LFCN.

Results

Literature review

The PubMed search resulted in 757 hits. A total of 66 articles were selected, in which a clear mechanism of LFCN injury or cause of compression was described that caused the symptoms of meralgia paresthetica. An overview of these articles is provided separately in Table 1 for different traumatic causes and Table 2 for different mass lesions.

Table 1.

Literature review of traumatic causes of meralgia paresthetica: result from 37 articles

| First author | Year of publication | Direct cause | Remarks on pathophysiologic mechanisms, onset symptoms, additional work-up and intra-operative findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Massey | 1977 | Standing at attention for 2 h | Lumbar lordosis, increased pelvic inclination and extension of the hip |

| Cascells | 1978 | Rotating tourniquet on thigh | Malfunctioning tourniquet with inflation >20 min |

| Grace | 1987 | Gastroplasty for morbid obesity | 3 cases, likely caused by Gomez retractor |

| Auriacombe | 1991 | Needle injury thigh | Accidental, drug needle |

| Parsonnet | 1991 | Coronary bypass surgery | Frog-leg position of legs during vein harvesting |

| Buch | 1993 | Fracture of ASIS | Acute onset |

| Andrew | 1994 | Laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy | 3 cases |

| Swezczyk | 1994 | Bodybuilder | Occurrence after training on leg press machine |

| Yamout | 1994 | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | External compression by surgeons positioned around table, alternative compression in the inguinal ligament secondary to extension hip |

| Thanikachalam | 1995 | Fracture of ASIS | Sudden sharp pain, importance plain radiography |

| Broecke, van den | 1998 | Iliac bone crest harvest | 3 cases, coring technique, potential anatomic variation |

| Hutchins | 1998 | Laparoscopic myomectomy | Injury probably due to retroperitoneal dissection |

| Schnatz | 1999 | Thigh injection with pain medication | Post-cesarean, but intraoperative damage unlikely |

| Butler | 2002 | Femoral artery cannulation for cardiac catheterization | Medial course LFCN |

| Polidori | 2003 | Laparoscopic appendectomy | LFCN damaged by insertion of trocar |

| Rajabally | 2003 | Repeated laparotomies | Bilateral case, scar tissue or due to retractors |

| Ulkar | 2003 | Direct trauma to anterolateral part thigh during soccer | Slightly decreased cutaneous sensation, provocative point on pressure distal to ASIS |

| Blake | 2004 | Seat-belt injury | Abrasion across chest extending to anterolateral region hip |

| Kavanagh | 2005 | Open appendicectomy | Anatomical variation in course LFCN |

| Kho | 2005 | Strenuous exercise | 2 cases walking, 1 case cycling |

| Paul | 2006 | Cesarian section | Bilateral case, due to puling or manipulation |

| Peters | 2006 | One case after total abdominal hysterectomy and one case post-cesarian | Possible causes: lithotomy position and pressure from self-retaining retractors |

| Park | 2007 | Wear of hip-huggers for 2 years | Lateral course of the LFCN (Aszmann type A) |

| Otoshi | 2008 | Baseball | Occurrence during pitching practice, intra-operatively LFCN pushed upward by a hard rim of the iliac fascia |

| Stephenson | 2008 | Lateral positioning on a bean bag | No soft contact layer |

| Hayashi | 2011 | Avulsion fracture of ASIS | Sudden onset, positive Tinel’s on percussing avulsed bony fragment of the ASIS |

| Yi | 2012 | Traumatic iliacus hematoma | Simultaneous femoral nerve compression |

| Hsu | 2014 | Avulsion fracture of ASIS and hematoma in sprinter | Diagnosed with US, confirmed with CT, treated conservatively |

| Satin | 2014 | Beach chair position for shoulder surgery | 4 cases, compression by patient’s abdominal pannus |

| Lagueny | 2015 | Injection of glatiramer acetate for MS | Lipoatrophy in proximal thigh and hyposensitivity in territory LFCN |

| Omichi | 2015 | Prone positioning | Distal entrapment underneath the fascia lata |

| Arends | 2016 | Subcutaneous interferon alpha treatment | Possible neurotoxic effect |

| Oh | 2017 | Femoral artery cannulation for cardiac catheterization | Bilateral meralgia paresthetica |

| Lee | 2018 | Sartorius muscle tear after jumping | Hematoma surrounding the LFCN on US |

| Marinelli | 2020 | Prone position ventilation | For COVID-19 infection, bilateral |

| Kot | 2021 | Placement and removal of pelvic fixator | Conservatively treated with US-guided injection of local anesthetics |

| Kokubo | 2022 | Park-bench position | Compression by fixture device |

Table 2.

Literature review of mass lesions causing meralgia paresthetica: results from 29 articles

| First author | Year publication | Mass lesion | Clue(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flowers | 1968 | Retroperitoneal lipofibrosarcoma | Continuous pain in thigh and to a lesser degree in the lumbosacral region |

| Good | 1981 | Bone bar after iliac bone graft harvest | Bony bar formed 5 years after harvest with nerve passing through it |

| Suber | 1979 | Uterine fibroid tumor compressing superior lumbar plexus | Sensory disturbance extended outside distribution are LFCN |

| Rinkel | 1990 | Metastasis vertebral body L2 | Compression nerve root L2 |

| Rotenberg | 1990 | Pelvic inflammatory disease | Bilasterale case |

| Amoiridis | 1993 | Malignant tumor psoas | Walking impossible due to intolerable increase in pain |

| Brett | 1997 | Abdominal aortic aneurysm | Sudden onset, back pain |

| Tharion | 1997 | Metastasis in iliac crest | Hard mass |

| Trummer | 2000 | Lumbar disc herniation, extraforaminal L2–L3 | Low back pain, advise MRI in all patients with meralgia |

| Yamamoto | 2001 | Hemangiomatosis | Diffuse swelling around ASIS |

| Yamamoto | 2001 | Heterotopic ossification | 40 years after iliac bone graft harvesting |

| Gupta | 2003 | Hip-joint synovial cyst | Firm swelling in iliac fossa |

| Ahmed | 2010 | Femoral acetabular impingement | Discovered on MRI thigh |

| Rau | 2010 | Lipoma | Relief after excision lipoma |

| Yang | 2010 | L1 radiculopathy | probably root L2, because of suspect disc S1-S2 on MRI |

| Yi | 2012 | Iliacus hematoma | Both femoral neuropathy and meralgia paresthetica |

| Talwar | 2012 | Peritoneal dialysis | Increased intra-abdominal pressure |

| Lonkar | 2012 | Spinal hydatid | Swelling back |

| Ramirez Huaranga | 2013 | Renal tumor | Large abdomen, mass on CT |

| Noh | 2015 | Pancreatic pseudocyst | Abdominal pain, palpable mass |

| Nishimura | 2015 | Appendicitis | Prolonged fever, acute lymphoblastic leukemia |

| Arabi | 2015 | Schwannoma at level L2 | Improvement after tumor resection |

| Magalhaes | 2019 | Pelvic osteochondroma | Thickening of iliac bone at palpation |

| Triplett | 2019 | Sartorius muscle fibrosis | Treated with cortisone injection |

| Gencer Atalay | 2020 | Inguinal lymphadenopathy | US-guided block with betamethasone and bupivacaine relieved pain |

| Makris | 2020 | Schwannoma LFCN | Improvement after tumor resection |

| Ganhao | 2021 | Lipomatosis | Small mass medial to ASIS |

| Seror | 2021 | Extraforaminal disc herniation L2-L3 | L2 radiculopathy |

| Toscano | 2021 | Giant hemorrhagic trochanteric bursitis | Mobile mass lesion |

Traumatic causes

Iatrogenic injury is one the most frequently reported causes for traumatic injury of the LFCN. As already mentioned in the introduction complication rates have been described for the anterior approach for hip surgery, acetabular fractures, the harvest of iliac bone crest and inguinal hernia repair. In the literature search we found additional articles describing cases after iliac crest bone harvest with the coring technique [8], laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy [10], and after different intra-abdominal surgical procedures [11, 12]. Most frequently reported cause was pressure or traction on the nerve due to retractor placement [11, 13] or manipulation [14, 15]. Other potential reported mechanisms of intraoperative injury were direct nerve injury due to retroperitoneal dissection [16], placement of a trocar [17] and placement and removal of a pelvic fixator [18].

Positioning of the patient also is a frequently reported cause for non-iatrogenic meralgia paresthetica, either by direct compression on the nerve by a fixture device [19], rotating tourniquet around the upper leg [20], positioning of the surgeons around the patient [21], prone positioning of the patient [22, 23], flexion of the hips as in lithotomy positioning for gynecologic and obstetric procedures [15], frog-leg positioning for vein harvest during coronary bypass surgery [24] and compression by patient’s abdominal pannus in beach chair position for shoulder surgery [25].

In addition, we found several cases of needle injury [26–29] and cases after femoral artery cannulation for cardiac catheterization [30, 31]. Reported potential mechanisms were direct needle injury, neurotoxic effect or from prolonged manual compression after cannulation [31].

Besides iatrogenic injury, several other traumatic causes have been reported including LFCN injury after seat-belt injury [32], avulsion fractures of the ASIS [33–36], sartorius muscle tear [37], traumatic iliacus hematoma [38], and several sports activities (including soccer [39], cycling [2], baseball [40]), long duration wear of hip-huggers [41] and standing at attention [42].

Mass lesions

Mass lesions causing symptoms of meralgia paresthetica were found along the entire course of the LFCN. Starting proximal, Rinkel et al. reported a case of meralgia paresthetica caused by compression of the nerve root L2 by a metastatic tumor of vertebral body L2 [43]. Other causes of L2 root compression included (extraforaminal) disc herniation of L2–L3 [44–46] and a schwannoma of L2 [47]. More distal causes were a uterine fibroid tumor compressing the superior lumbar plexus [48], a malignant tumor in the psoas [49], a retroperitoneal lipofibrosarcoma [50], a renal tumor [51], a pancreatic pseudocyst [52], an abdominal aortic aneurysm [53], a metastasis of the iliac crest [54], a synovial cyst in the iliac fossa [55] and a hematoma of the iliac muscle [38]. In addition, multiple causes of LFCN compression have been reported around the SIAS, including hemangiomatosis [56], heterotopic ossification [57, 58] and a pelvic osteochondroma [59]. Finally, multiple distal sites of compression have been found to cause symptoms of meralgia paresthetica including lipoma/lipomatosis [60, 61], fibrosis of the sartorius muscle [62], inguinal lymphadenopathy [63], femoral acetabular impingement [64], giant hemorrhagic trochanteric bursitis [65] and a schwannoma inside the LFCN [66]. Besides cases with a cause of compression along the course of the LFCN, also cases have been reported on more diffuse compression by increased intra-abdominal pressure: one bilateral case due to pelvic inflammatory disease [67] and one case after peritoneal dialysis [68].

Signs that pointed at an unusual cause for meralgia paresthetica were sudden onset of symptoms, sensory disturbance outside distribution area of the LFCN, accompanying symptoms of back pain or fever or the presence of a swelling in the groin area. Other factors that raised suspicion were an oncologic history and continuous severe symptoms.

Single center experience with traumatic cases of the LFCN

Between April 1, 2014 and September 1, 2022 a total of 187 primary procedures were performed for meralgia paresthetica in our Center. Fourteen cases had a traumatic cause (Table 3).

Table 3.

14 traumatic causes of meralgia paresthetica

| Traumatic cause | Number of cases | Interval trauma-presentation | Remarks | Procedure | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip surgery | 3 THP, 1 intramedullary rod femur | 1.5–3 yrs | 2 cases complete transection, 1 neuroma, 1 anatomical variant type E | Neurectomy (4) | Complete pain relief in 2 cases; other 2 cases no effect |

| Fixation acetabular fracture | 1 | 5 yrs | Type D variant | Neurolysis | Temporary pain relief |

| Seat-belt injury | 2 | 1 yr | Neurectomy (2) | Almost complete pain relief in both cases: one case recurrence 7 years after neurectomy, complete relief following suprainguinal re-resection | |

| Bike accidents | 2 | 5 yrs | Neurexeresis (1), neurolysis (1) | Partial pain relief after neurexeresis, no relief after neurolysis | |

| Inguinal hernia repair | 2 | 6 mo | 1 open: 1 scopic, anatomical variant (type E) | Neurolysis (1), neurectomy (1) | 1 good results after neurolysis, 1 recurrence of symptoms after neurolysis |

| Vascular surgery for false aneurysm iliac artery | 1 | 1.5 yrs | Neurectomy | Almost complete pain relief | |

| Abdominal uterus extirpation | 1 | 1 yr | Neurolysis | Complete pain relief | |

| Heparin injection | 1 | 9 mo | Neurolysis followed by neurectomy | No pain relief after neurolysis, complete pain relief after neurectomy |

The most frequent cause for iatrogenic injury in our series was the anterior approach for hip surgery (4), followed by seat-belt injury (2), bike accidents (2) and inguinal hernia repair (2). In addition, we surgically treated several other cases of iatrogenic injury caused by procedures around the ASIS. Most remarkable finding was the long interval between trauma and referral. Further, there was a relatively high number of cases with an anatomical variation in the course of the LFCN, most frequently a relatively medial course (type D and E according to the classification by Aszmann et al [1]).

Overall, outcome after surgery was variable: neurectomy for traumatic LFCN injury after hip surgery resulted in pain relief in half of the cases (2 out of 4).

Single center experience with mass lesion compressing the LFCN

In addition to the traumatic cases, four cases of meralgia paresthetica were identified caused by compression of the LFCN by a mass lesion. The separate cases are described below using the CARE guidelines [69]:

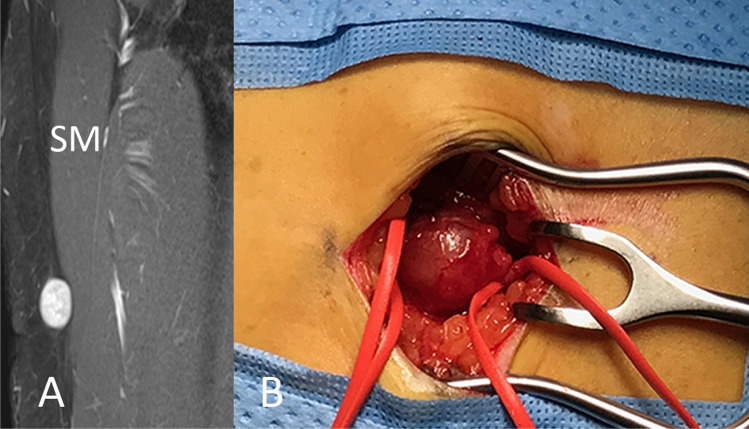

Case of a Schwannoma in the LFCN

A 41-year-old female was referred to our hospital, because of a tingling sensation in her right thigh to just below the knee that had lasted for half a year. In addition, she had noticed a swelling in the anterolateral part of her right upper leg for several months. She had no relevant medical history. During neurologic examination the swelling itself was not painful, but pressure given on top of the lesion exacerbated the symptoms of meralgia paresthetica. An MRI scan was made of her right upper leg, which showed an oval, well-circumscribed mass lesion of 10 mm inside the LFCN (Fig. 2A). She was operated in supine position. The lesion was localized with intraoperative ultrasound. A vertical incision was made over the localized lesion. The LFCN and the lesion inside the LFCN were exposed. After opening of the capsule, the tumor could be resected with sparing of the normal fascicles. Histopathologic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of a schwannoma. Three months after the surgery the patient had no more symptoms of meralgia paresthetica. She still had some numbness in the anterolateral part of her leg, but she was not bothered by this numbness. MRI showed no residual tumor.

Fig. 2.

Case of schwannoma inside the LFCN. A: Coronal T1-weighted MR image showing a well-circumscribed lesion inside the LFCN with homogenous gadolinium enhancement. The lesion was positioned on top of the sartorius muscle (SM). B: Intraoperative picture showing the schwannoma with bands placed around the LFCN proximal and distal to the lesion

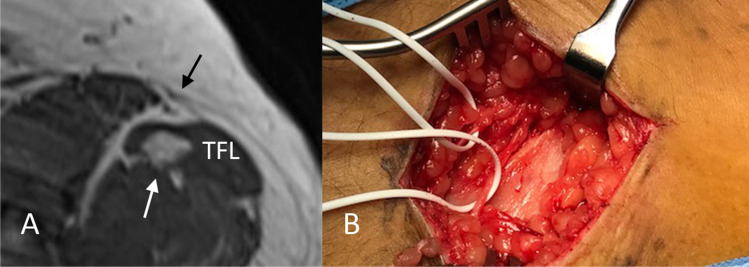

Case of a lipoma in the tensor fascia

A 48-year-old male with a history of multiple lipomas was referred to our hospital, because of a burning sensation in the anterolateral part of his thigh. He had no relevant medical history and specifically no history of lipomatosis. An MRI scan was made, which showed a lipoma of 1-cm diameter inside the tensor fascia latae muscle (Fig. 3A). Intraoperatively the lipoma was localized with ultrasound. A vertical incision was made in the skin on top of the lesion, and the distal branches of the LFCN were identified (Fig. 3B). Subsequently the fascia of the underlying tensor fascia latae muscle was opened, the lipoma was identified and resected. Histopathologic analysis confirmed the diagnosis of a lipoma. Three months after the surgery the patient had complete relief of his pain symptoms.

Fig. 3.

Case of lipoma inside the tensor fascia latae muscle. A: Transverse T1-weighted MR image showing a lesion of 1cm in diameter in the tensor fascia latae muscle (TFL) with high signal intensity comparable to that of subcutaneous fat (white arrow). The black arrow points at the branches of the LFCN. B: Intra-operative image with white bands placed around the separate branches of the LFCN after opening of the fascia lata

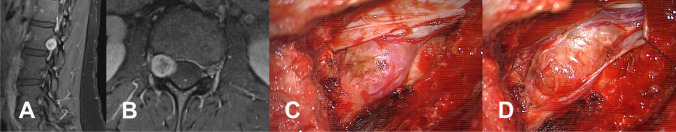

Case of a Schwannoma of the L2 nerve root

A 37-year-old woman with an 8-year history of meralgia paresthetica on the right side was referred with a lesion in her right L2 nerve root. She had been diagnosed with meralgia paresthetica 8 years ago. Her pain symptoms had substantially increased over the last 2-3 years, which was the reason why the referring neurologist had ordered the MRI scan. This showed a lesion in the right L2 nerve root (Fig. 4A). The patient had no relevant medical history. During neurologic examination no abnormalities were found. She was operated in prone position under general anesthesia. The lesion was exposed through a facetectomy L2–L3 on the right side (Fig. 4B). The sleeve of the nerve root and part of the dura was opened to expose the lesion and intradural filaments. The lesion could be resected totally by transecting the dorsal root filament with sparing of the ventral root filament. Pathologic analysis showed a Schwannoma. After the surgery she had no more pain symptoms in the anterolateral part of the thigh. She had decrease sensation in this area, but the numbness did not bother her. Postoperative MRI scans showed no residual or recurrent tumor up to 2 years after the surgery.

Fig. 4.

L2 Case of L2 nerve root schwannoma: A and B: sagittal and transverse T1-weighted MR images after gadolinium showing the schwannoma inside the L2 nerve root on the right side. C and D: intra-operative pictures showing the schwannoma before and after opening of the dura

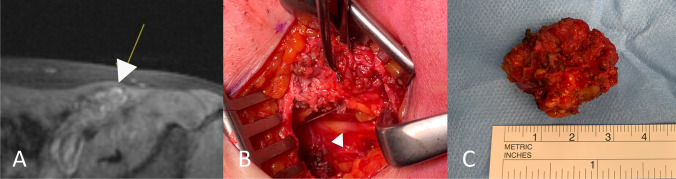

Case of endometriosis in the inguinal ligament

A 37-year-old woman with 5-year history of meralgia paresthetica on the left side was referred with a nodule on top of the left inguinal ligament suspect for endometriosis. She had continuous pain symptoms, but the severity substantially increased menstruation (numeric rating score increased during these periods from 5 to 8). She had a history of endometriosis. During neurologic examination, the lesion could be palpated in her left groin, and pressure on the lesion increased her pain symptoms. MRI scan (Fig. 5A) showed a nodule of 12-mm diameter. US showed a medial course of the LFCN with compression by the nodule. Patient was operated through a suprainguinal approach. The lesion was identified on top of the inguinal ligament. After mobilization of the lesion, the underlying LFCN could be identified (Fig. 5B). The nerve itself was not affected by the endometriosis. The lesion was totally removed (Fig. 5C). Patient experienced complete pain relief 3 months after surgical removal.

Fig. 5.

Case of endometriosis in the groin area: A: Transverse T1-weighted image with gadolinium showing the endometriosis lesion (white arrow) inside the inguinal ligament. B: Intra-operative image showing the LFCN (arrow) after mobilization of the endometriosis lesion. C: Picture of endometriosis lesion

Discussion

Although surgery is most frequently performed for idiopathic meralgia paresthetica [70], it is important to consider the possibility of a previous trauma or compression by a mass lesion in the evaluation of patients with meralgia paresthetica and check for potential signs that may point at a traumatic cause or compression by a mass lesion. In this article we reviewed the literature and presented our own experience with the surgical treatment of traumatic cases of meralgia and cases caused by compression due to mass lesions. For clarity reasons we will discuss these two categories separately below.

Traumatic injury of the LFCN

As we expected, iatrogenic injury was the most frequently reported traumatic cause for LFCN injury in the literature. Besides the procedures that are well known for the potential of causing LFCN injury, we found several cases of meralgia after intra-abdominal procedures performed both through an open and laparoscopic approach. Several pathophysiologic mechanisms for injury have been reported including direct injury to the LFNC, for example during retroperitoneal dissection [16] or due to insertion of the trocar [17], or indirect injury due to manipulation or retraction by surgical blades [11]. The latter explanation is also supported by the finding of bilateral meralgia in 2 cases after laparotomy [13 14]. Other mechanisms that were mentioned included increased abdominal pressure (due to induced pneumoperitoneum [21]) and positioning of the patient, such as extreme lithotomy position [15].

In this study we did not include all studies on the effect of surgical positioning, because most studies concern series without description of the individual cases. Potential causes mentioned in these articles include pannicular traction at the inguinal ligament, extreme flexion of the hips or direct compression by a fixture device [19]. Unfortunately, the LFCN is not mentioned in the ASA Practice Advisory for the Prevention of Perioperative Peripheral Neuropathies [71], probably because of the low incidence and the fact that is often self-limiting (53% of the symptoms recover within first week after spine surgery, and every patient within 2 months [72]). Nevertheless, we feel that more awareness should be raised for the potential complication of meralgia paresthetica after positioning for different surgical procedures both for patient education and adequate conservative treatment.

Furthermore, our literature review showed several iatrogenic cases after femoral artery cannulation and needle injury either caused by direct injury of the needle, neurotoxic effect of the injected drug and/or compression after removal of the needle or cannula for hemostasis.

Finally, several cases have been reported of traumatic meralgia paresthetica after different sports activities. Although these cases are more difficult to distinguish from idiopathic meralgia paresthetica and the trauma may be regarded as predisposing rather than as direct cause, sometimes there was clear relation between the occurrence of symptoms and a certain activity. Otoshi et al. for example reported a case of meralgia paresthetica in baseball player and hypothesized that injury to the nerve was caused by contraction of the iliac muscles during pitching motion [40]. Other cases have been reported after training on a leg press [73], extensive walking and cycling [2] and long duration of standing at attention [42]. Direct impact on the anterolateral part of the thigh may also lead to symptoms of meralgia paresthetica, as for example shown by the case of Ulkar et al., who found symptoms after direct trauma in a soccer patient [39]. A lateral course of the LFCN (type A, where the nerve runs lateral to the ASIS) probably makes the nerve more vulnerable to injury (as seen in the case by Park et al [41]). Specific attention should be paid to a potential distal injury at the site where the branch(es) pierce the fascia lata to innervate the skin [23].

In our own series of 14 traumatic cases, we also observed the types of injury that are most frequently reported in the literature, including the anterior approach for hip surgery (4 cases), inguinal hernia repair (2 cases) and seat-belt injury (2 cases). Interestingly, we also operated two cases of injury after bicycle accidents, which can be explained by the frequent use of bicycles for transportation in the Netherlands [74]. Overall, outcome after surgery in our small series was variable. Neurectomy of the LFCN after traumatic injury for anterior hip surgery resulted in pain relief in only half of the cases. This could be due to referral bias, because transection injury was most frequently observed in our cases, whereas Goulding et al. found that most injuries after the anterior approach for hip arthroplasty concern neurapraxia [75]. In the literature there are only a few articles in which surgical results for traumatic cases have been described and the series are heterogenous with often different traumatic causes [3, 76, 77]. More research is needed to investigate the role of surgery after traumatic LFCN injury. In any event, it is important to recognize the possibility of LFCN injury and preferably perform additional analysis with ultrasound pre-operatively, also to investigated potential hematoma, muscle tear and /or avulsion of a fragment of the ASIS. We suspect that traumatic injuries of the LFNC are frequently missed. In addition, we observed a substantial delay in the referral of these patients. After seat-belt injury for example (where the LFCN is vulnerable at the site where the seat belt runs just caudal to the ASIS and sudden deceleration of the car with tightening of the seatbelt might lead to compression injury of the nerve). As was shown in the case by Blake and Treble [32], abrasion across the chest extending to the anterolateral region of the hip may point at this, although these abrasions may not always be found and, as in our experience, patients are often referred years after the injury has occurred.

The most frequently reported finding from our series of traumatic cases was a relatively medial course of the LFCN. In the classification by Aszmann et al. this type is referred to as type D and E [1]. It could be that the more lateral course, where the nerve runs just medial to the ASIS (type B and C), protects the LFCN from injury or that surgeons are not aware of potential medial course of the nerve. More studies, as the one by Broin et al. [9], are needed to investigate safe margins for different procedures. Moreover, because medial variants may also be injured after femoral artery cannulation, it is important to realize that digital compression and the use compression devices [30] can lead to LFCN injury, and possibly, preventive measures such as the use of vascular closure device may prevent this complication [31].

Besides the more frequently reported traumatic causes of meralgia paresthetica, we also found several unusual causes, including nerve injury after heparin injection, vascular surgery for a false aneurysm of the iliac artery, abdominal uterus extirpation and fixation of an acetabular fracture. As expected for unusual cases, there was often a referral bias, and multiple scans had been performed before the patient was referred. In our experience it is helpful in these cases to perform analysis with ultrasound to investigate the possibility of a neuroma, hematoma or fibrosis. In addition, pressure with the probe of the US over the area of the injury may provoke symptoms (sonopalpation), which may also point at a traumatic mechanism of injury.

Compression by mass lesions

Our literature review shows that potential causes of compression can be found anywhere along the course of the LFCN. Proximally several lesions were found that presented with symptoms of meralgia paresthetica, often accompanied by back pain, which pointed at another potential cause than idiopathic meralgia paresthetica. Lumbar radiculopathy of L2 or L3 is probably the most important differential diagnosis of meralgia paresthetica. Yang et al. reported a case of L1 radiculopathy mimicking meralgia paresthetica caused by L1–L2 intervertebral disc herniation, but the MRI in their figure suggests a rudimentary disc S1–S2, and we question whether in that case the affected level was in fact L2–L3 [46]. Some authors recommend MRI to exclude a potential compression at the spinal level in all patients with meralgia paresthetica [44]. We would suggest to at least perform MRI in the presence of radicular pain symptoms (rather than dysesthesia which is often observed in meralgia), accompanying backpain, extension of the symptoms outside the distribution area of the LFCN and in case additional work-up for meralgia paresthetica is normal (no increased surface area of the LFCN on US or intraneural edema) and if there is no response to local nerve block.

Other clues that may point at another cause noted in the literature were an oncologic history, abnormal presentation (continuous severe symptoms or short duration), swelling around the ASIS or intra-abdominal swelling. Some articles have reported the occurrence of meralgia following pelvic inflammatory disease. The exact pathophysiologic mechanism in these cases remains unclear, but it may be explained by extension of the intra-abdominal contention and secondary compression of the LFCN. Another explanation could be inguinal lymphadenopathy [63]. In our experience ultrasound (US) is helpful to rule other mass lesions around the ASIS. Another advantage of US is that it can be used preoperatively to determine the anatomical variant in the course of the LFCN in relation to the ASIS [78].

In our surgical series we found 4 cases of compression of the LFCN, including two cases of schwannoma, one case of lipoma and one case of endometriosis. A few other cases of schwannoma involving the LFCN have been described in the literature: one case involving the LFCN [66] and one intradural case at the level L2 [47]. Also compression of the LFCN by a lipoma has been described previously [60 61]: one case was treated surgically [60] and one case by injection of triamcinolone and lidocaine [61]. To the best of our knowledge no other cases have been reported on cyclic symptoms of meralgia paresthetica related to menstruation due to endometriosis. In our case symptoms were caused by direct compression of the endometriosis lesion at the inguinal ligament. Although these causes are rare, in our opinion it is important to rule out a potential alternative cause, especially when there are accompanying signs such back pain, swelling in the groin or the anterolateral part of the thigh or a history of schwannomatosis, lipomatosis or endometriosis.

Conclusion

As our literature review shows there are multiple iatrogenic and other traumatic causes for meralgia paresthetica. Sometimes the trauma mechanism is clear, but sometimes (especially in closed injury) the trauma mechanism is not recognized and patients are referred with a substantial delay. More awareness should be raised for potential occurrence of meralgia paresthetica after positioning for surgery, including prone-positioning for spine surgery.

Our literature review also shows that meralgia paresthetica can be caused by mass lesions all along the course of the LFCN, starting from the nerve root L2/L3 up to the distal branches of the LFCN to the skin. Accompanying signs such as atypical presentation (sudden onset, severe pain), accompanying symptoms (back pain), local swelling in the groin area and an oncologic history may point at an alternative cause. Ultrasound can be performed to investigate structural abnormalities around the ASIS. Additional work-up (including MRI of the lumbar spine) should be performed in case of suspicion of L2 or L3 nerve root compression.

Supplementary information

Availability of data and materials

Details can be requested from the corresponding author, but restricted to the guidelines and only with permission from the Medical Ethical Committee South-West Netherlands.

Author contributions

GdR selected and read all articles, wrote the manuscript (including the case descriptions), reviewed the final version and revised the manuscript according to the comments by the reviewers. JO reviewed the first and the revised version of the manuscript. TV participated in the literature search and reviewed the first and revised version of the manuscript. AK read all articles in the review and reviewed the revised version of the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Medical Ethical Committee from the South-West Netherlands and from the board of the Haaglanden Medical Center.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Aszmann OC, Dellon ES, Dellon AL. Anatomical course of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and its susceptibility to compression and injury. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(3):600–604. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199709000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kho KH, Blijham PJ, Zwarts MJ. Meralgia paresthetica after strenuous exercise. Muscle Nerve. 2005;31(6):761–763. doi: 10.1002/mus.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahabedian MY, Dellon AL. Meralgia paresthetica: etiology, diagnosis, and outcome of surgical decompression. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35(6):590–594. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199512000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida S, Oya S, Matsui T. Risk factors of meralgia paresthetica after prone position surgery: possible influence of operating position, laminectomy level, and preoperative thoracic kyphosis. J Clin Neurosci. 2021;89:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2021.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahm F, Aichmair A, Dominkus M, Hofstaetter JG. Incidence of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve lesions after direct anterior approach primary total hip arthroplasty—a literature review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2021;107(8):102956. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2021.102956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lao A, Putman S, Soenen M, Migaud H. The ilio-inguinal approach for recent acetabular fractures: ultrasound evaluation of the ilio-psoas muscle and complications in 24 consecutive patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(4):375–378. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murata Y, Takahashi K, Yamagata M, Shimada Y, Moriya H. The anatomy of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, with special reference to the harvesting of iliac bone graft. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(5):746–747. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200005000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van den Broecke DG, Schuurman AH, Borg ED, Kon M. Neurotmesis of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve when coring for iliac crest bone grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(4):1163–1166. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199809040-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broin EO, Horner C, Mealy K, et al. Meralgia paraesthetica following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: An anatomical analysis. Surg Endosc. 1995;9(1):76–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00187893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrew DR, Gregory RP, Richardson DR. Meralgia paraesthetica following laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy. Br J Surg. 1994;81(5):715. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grace DM. Meralgia paresthetica after gastroplasty for morbid obesity. Can J Surg. 1987;30(1):64–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kavanagh D, Connolly S, Fleming F, Hill AD, McDermott EW, O’Higgens NJ. Meralgia paraesthetica following open appendicectomy. Ir Med J. 2005;98(6):183–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajabally YA, Farrell D. Bilateral meralgia paraesthetica following repeated laparotomies. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10(3):330–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul F, Zipp F. Bilateral meralgia paresthetica after cesarian section with epidural analgesia. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2006;11(1):98–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2006.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters G, Larner AJ. Meralgia paresthetica following gynecologic and obstetric surgery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95(1):42–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchins FL, Jr, Huggins J, Delaney ML. Laparoscopic myomectomy—an unusual cause of meralgia paresthetica. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1998;5(3):309–311. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(98)80039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polidori L, Magarelli M, Tramutoli R. Meralgia paresthetica as a complication of laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(5):832. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-4279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kot P, Rubio-Haro R, Bordes-Garcia C, Ferrer-Gomez C, De Andres J. Meralgia paresthetica after pelvic fixation in a polytrauma patient. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2021;74(6):555–556. doi: 10.4097/kja.21065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kokubo R, Kim K, Umeoka K, Isu T, Morita A. Meralgia paresthetica caused by surgery in the park-bench position. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022;89(3):355–357. doi: 10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2022_89-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cascells W, Resnick N, Thalinger K, Herzog A. Meralgia paresthetica due to unusual compression. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(5):285. doi: 10.1056/nejm197802022980527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamout B, Tayyim A, Farhat W. Meralgia paresthetica as a complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1994;96(2):143–144. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marinelli L, Mori L, Avanti C, et al. Meralgia paraesthetica after prone position ventilation in a patient with COVID-19. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7(12):002039. doi: 10.12890/2020_002039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omichi Y, Tonogai I, Kaji S, Sangawa T, Sairyo K. Meralgia paresthetica caused by entrapment of the lateral femoral subcutaneous nerve at the fascia lata of the thigh: a case report and literature review. J Med Invest. 2015;62(3-4):248–250. doi: 10.2152/jmi.62.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parsonnet V, Karasakalides A, Gielchinsky I, Hochberg M, Hussain SM. Meralgia paresthetica after coronary bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(2):219–221. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(19)36755-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satin AM, DePalma AA, Cuellar J, Gruson KI. Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy following shoulder surgery in the beach chair position: a report of 4 cases. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2014;43(9):E206–E209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auriacombe M, Dhopesh V, Yagnik P. Meralgia paresthetica syringectica. JAMA. 1991;265(21):2807–2808. doi: 10.1001/jama.1991.03460210053015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnatz P, Wax JR, Steinfeld JD, Ingardia CJ. Meralgia paresthetica: an unusual complication of post-cesarean analgesia. J Clin Anesth. 1999;11(5):416–418. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(99)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lagueny A, Ouallet JC. Meralgia paresthetica after subcutaneous injection of glatiramer acetate. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52(1):150–151. doi: 10.1002/mus.24614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arends S, Wirtz PW. Meralgia paresthetica in subcutaneous interferon alpha treatment. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2016;18(1):44. doi: 10.1097/CND.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butler R, Webster MW. Meralgia paresthetica: an unusual complication of cardiac catheterization via the femoral artery. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;56(1):69–71. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oh SI, Kim EG, Kim SJ. An unusual case of bilateral meralgia paresthetica following femoral cannulations. Neurointervention. 2017;12(2):122–124. doi: 10.5469/neuroint.2017.12.2.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blake SM, Treble NJ. Meralgia paraesthetica—an addition to ‘seatbelt syndrome’. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86(6):W6–W7. doi: 10.1308/14787080456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buch KA, Campbell J. Acute onset meralgia paraesthetica after fracture of the anterior superior iliac spine. Injury. 1993;24(8):569–570. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(93)90043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thanikachalam M, Petros JG, O’Donnell S. Avulsion fracture of the anterior superior iliac spine presenting as acute-onset meralgia paresthetica. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26(4):515–517. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi S, Nishiyama T, Fujishiro T, Kanzaki N, Kurosaka M. Avulsion-fracture of the anterior superior iliac spine with meralgia paresthetica: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2011;19(3):384–385. doi: 10.1177/230949901101900327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsu CY, Wu CM, Lin SW, Cheng KL. Anterior superior iliac spine avulsion fracture presenting as meralgia paraesthetica in an adolescent sprinter. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46(2):188–190. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee B, Stubbs E. Sartorius muscle tear presenting as acute meralgia paresthetica. Clin Imaging. 2018;51:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2018.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yi TI, Yoon TH, Kim JS, Lee GE, Kim BR. Femoral neuropathy and meralgia paresthetica secondary to an iliacus hematoma. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012;36(2):273–277. doi: 10.5535/arm.2012.36.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ulkar B, Yildiz Y, Kunduracioglu B. Meralgia paresthetica: a long-standing performance-limiting cause of anterior thigh pain in a soccer player. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(5):787–789. doi: 10.1177/03635465030310052601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otoshi K, Itoh Y, Tsujino A, Kikuchi S. Case report: meralgia paresthetica in a baseball pitcher. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(9):2268–2270. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0307-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park JW, Kim DH, Hwang M, Bun HR. Meralgia paresthetica caused by hip-huggers in a patient with aberrant course of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35(5):678–680. doi: 10.1002/mus.20721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Massey EW. Meralgia paraesthetica. An unusual case. JAMA. 1977;237(11):1125–1126. doi: 10.1001/jama.1977.03270380069026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rinkel GJ, Wokke JH. Meralgia paraesthetica as the first symptom of a metastatic tumor in the lumbar spine. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1990;92(4):365–367. doi: 10.1016/0303-8467(90)90067-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trummer M, Flaschka G, Unger F, Eustacchio S. Lumbar disc herniation mimicking meralgia paresthetica: case report. Surg Neurol. 2000;54(1):80–81. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(00)00264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seror P. Meralgia paresthetica related to L2 root entrapment. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(6):E55–E57. doi: 10.1002/mus.27228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang SN, Kim DH. L1 radiculopathy mimicking meralgia paresthetica: a case report. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41(4):566–568. doi: 10.1002/mus.21601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arabi H, Khalfaoui S, El Bouchti I, et al. Meralgia paresthetica with lumbar neurinoma: case report. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2015;58(6):359–361. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2015.07.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suber DA, Massey EW. Pelvic mass presenting as meralgia paresthetica. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53(2):257–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amoiridis G, Wohrle J, Grunwald I, Przuntek H. Malignant tumour of the psoas: another cause of meralgia paraesthetica. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;33(2):109–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flowers RS, Meralgia paresthetica. A clue to retroperitoneal malignant tumor. Am J Surg. 1968;116(1):89–92. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(68)90423-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramirez Huaranga MA, Ariza Hernandez A, Ramos Rodriguez CC, Gonzalez GJ. What meralgia paresthetica can hide: renal tumor as an infrequent cause. Reumatol Clin. 2013;9(5):319–321. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Noh KH, Kim DS, Shin JH. Meralgia paresthetica caused by a pancreatic pseudocyst. Muscle Nerve. 2015;52(4):684–685. doi: 10.1002/mus.24701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brett A, Hodgetts T. Abdominal aortic aneurysm presenting as meralgia paraesthetica. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997;14(1):49–51. doi: 10.1136/emj.14.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tharion G, Bhattacharji S. Malignant secondary deposit in the iliac crest masquerading as meralgia paresthetica. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;78(9):1010–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gupta R, Stafford S, Cox N. Unusual cause of meralgia paraesthetica. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42(8):1005. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamamoto T, Kurosaka M, Marui T, Mizuno K. Hemangiomatosis presenting as meralgia paresthetica. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(3):518–520. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.21624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamamoto T, Nagira K, Kurosaka M. Meralgia paresthetica occurring 40 years after iliac bone graft harvesting: case report. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(6):1455–1457. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200112000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Good CJ. Meralgia paraesthetica as a complication of bone grafting. Injury. 1981;13(3):260. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(81)90253-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.BM LV, Massardi FR, SA CP Pelvic osteochondroma causing meralgia paresthetica. Neurol India. 2019;67(3):928–929. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.263206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rau CS, Hsieh CH, Liu YW, Wang LY, Cheng MH. Meralgia paresthetica secondary to lipoma. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12(1):103–105. doi: 10.3171/2009.7.SPINE08622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ganhao S, Uson J. Meralgia paresthetica secondary to underlying lipomatosis: an unusual case. J Clin Rheumatol. 2021;27(7):S836–SS37. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Triplett JD, Robertson A, Yiannikas C. Compressive lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy secondary to sartorius muscle fibrosis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(1):109–110. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gencer Atalay K, Giray E, Yolcu G, Yagci I. Meralgia paresthetica caused by inguinal lymphadenopathy related to tinea pedis infection: a case report. Turk J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;66(4):473–475. doi: 10.5606/tftrd.2020.4459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahmed A. Meralgia paresthetica and femoral acetabular impingement: a possible association. J Clin Med Res. 2010;2(6):274–276. doi: 10.4021/jocmr468w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toscano A, Costa GG, Rocchi M, Saracco A, Pignatti G. Giant hemorrhagic trochanteric bursitis mimicking a high-grade soft tissue sarcoma: report of two cases. Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S1):e2021043. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92iS1.9151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Makris AP, Makris D. Schwannoma of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, an unusual cause of meralgia paresthetica: a case report. J Orthop Case Rep. 2020;10(8):80–83. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2020.v10.i08.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rotenberg AS. Bilateral meralgia paresthetica associated with pelvic inflammatory disease. CMAJ. 1990;142(1):42–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Talwar A, Baharani J (2012) Meralgia paraesthetica: an unusual complication in peritoneal dialysis. BMJ Case Rep 2012:1–2. 10.1136/bcr.01.2012.5590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG et al (2013) The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep 2013:1–4. 10.1136/bcr-2013-201554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Lu VM, Burks SS, Heath RN, Wolde T, Spinner RJ, Levi AD (2021) Meralgia paresthetica treated by injection, decompression, and neurectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of pain and operative outcomes. J Neurosurg:1–11. 10.3171/2020.7.JNS202191 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Apfelbaum JL, Agarkar M, Connis RT, et al. an updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Prevention of Perioperative Peripheral Neuropathies. Anesthesiology. 2018;128(1):11–26. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang SH, Wu CC, Chen PQ. Postoperative meralgia paresthetica after posterior spine surgery: incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(18):E547–E550. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000178821.14102.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Szewczyk J, Hoffmann M, Kabelis J. Meralgia paraesthetica in a body-builder. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 1994;8(1):43–45. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Guerre L, Sadiqi S, Leenen LPH, Oner CF, van Gaalen SM. Injuries related to bicycle accidents: an epidemiological study in The Netherlands. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020;46(2):413–418. doi: 10.1007/s00068-018-1033-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goulding K, Beaule PE, Kim PR, Fazekas A. Incidence of lateral femoral cutaneous nerve neuropraxia after anterior approach hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(9):2397–2404. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ataizi ZS, Ertilav K, Ercan S. Surgical options for meralgia paresthetica: long-term outcomes in 13 cases. Br J Neurosurg. 2019;33(2):188–191. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2018.1538480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ducic I, Dellon AL, Taylor NS. Decompression of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve in the treatment of meralgia paresthetica. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2006;22(2):113–118. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-932505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.de Ruiter GCW, Wesstein M, Vlak MHM. Preoperative ultrasound in patients with meralgia paresthetica to detect anatomical variations in the course of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. World Neurosurg. 2021;149:e29–e35. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.02.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.