“Dragon man” prompts rethinking of Middle Pleistocene hominin systematics in Asia (original) (raw)

Dear Editor,

Chibanian (Middle Pleistocene) hominin fossils that could not be easily assigned to Homo erectus, H. neanderthalensis, or H. sapiens have traditionally been assigned to an all-inclusive group: “archaic H. sapiens.” In an insightful observation of the Chibanian record almost four decades ago however, Tattersall railed against the use of the word “archaic” in this sense when referring to the human fossil record, as he justifiably noted that no other biological organism has the word “archaic” attached to it.1 For example, no one refers to an earlier version of Canis domesticus as “archaic” C. domesticus. The ancestor of the domestic dog is, and always has been, considered to be C. lupus. In Tattersall’s opinion, it would seem that these “archaic _H. sapiens_” fossils should be assigned to one or more formal taxonomic names. As such, terms such as “archaic H. sapiens,” “mid-Pleistocene Homo,” and “Middle Pleistocene _Homo_” have always been considered to be wastebasket taxa that include way too much morphological variability for one proposed taxonomic group. Continuing to use wastebasket taxa only hinders any attempts to understand true phylogenetic and evolutionary relationships.

In more recent decades, there has been a push, primarily by Western paleoanthropologists, to assign these archaic H. sapiens fossils to another all-inclusive taxon: H. heidelbergensis.2,3 This would include all of the fossils from Europe, Africa, and East Asia. However, some researchers have questioned the utility of H. heidelbergensis representing all Chibanian hominins not named erectus, neanderthalensis, or sapiens.4 At least part of the reason is due to the recent publication of new Chibanian taxa in places such as South Africa (H. naledi)5 and China (H. longi).6 Furthermore, questions have long been raised about trying to assign the Chinese fossils to the H. heidelbergensis hypodigm, given that the hominins from eastern Asia look quite different from similarly aged fossils from western Eurasia and Africa (Figure 1 inset).

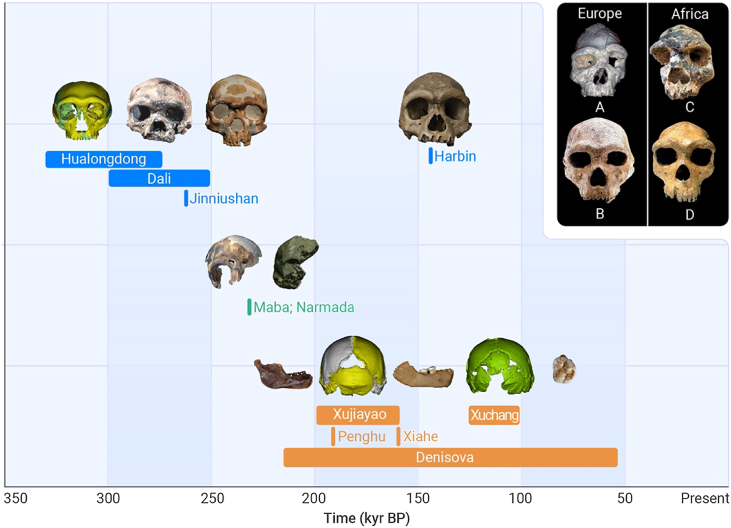

Figure 1.

Proposed groupings for the Chinese/Asian fossils

Group 1 includes Harbin, Dali, Jinniushan, and Hualongdong; group 2 includes Maba and Narmada (Hathnora); and group 3 includes Xujiayao, Xuchang, Xiahe, Penghu, and Denisova. Inset: for comparative purposes, these are representative Chibanian fossils from Europe (A, Arago; B, Petralona) and Africa (C, Bodo; D, Kabwe).

Available nomina

The Chinese Chibanian hominin fossil record is taking on an increasingly important role in this debate. An important observation from this time period is that there is a greater amount of hominin morphological variability present than originally hypothesized. How to organize all of this variation is the next logical step in this process. Unfortunately, because Chinese (and many westerners familiar with the Chinese record) paleoanthropologists have traditionally viewed the Chibanian hominin fossil record as transitional between H. erectus and H. sapiens these fossils have long been referred to simply as “archaic” or “early” H. sapiens. This may be part of the reason that almost a century passed between Davidson Black’s formal announcement of Sinanthropus pekinensis in 1928 and H. longi in 2021. But is it true that no Chinese Chibanian hominin taxonomic names have been formally published and available between S. pekinensis and H. longi? We delve more deeply into this question, particularly given how important the Chinese record is to these debates in paleoanthropology. In fact, with the recent announcement and description of the new H. longi type specimen (Harbin) by Ni et al.,6 other possible taxonomic names seem to have been raised as possibly available, and importantly, would have priority (e.g., H. daliensis, H. mapaensis).

A good example of this is that an argument has been made (on social media) that on the basis of morphological similarities, the type specimen of H. longi, the Harbin cranium, should be assigned to H. daliensis. The justification for this argument is that the Dali specimen was supposedly published as a new species and would have priority. We conducted an extensive review of this argument and conclude that Xinzhi Wu had proposed the Dali cranium as a possible subspecies of H. sapiens. In the original 1981 publication in English, Wu wrote that “it is suggested that Dali cranium probably represents a new subspecies, _Homo sapiens daliensis_” (p. 538).7 Even in the original Chinese version of the paper however, Wu used the term “probably” to describe Dali as a possible new subspecies.7 Furthermore, in all of Wu’s follow up publications, H. daliensis does not appear as a separate species. In other words, Wu did not discuss or consider Dali in formal taxonomic terms and certainly not as a new subspecies or species in his more recent publications. In fact, other than in his 1981 paper, Wu always referred to the Dali fossil as “archaic” H. sapiens. It is our experience, which includes many direct discussions with him, that Wu strongly believed that all Chinese Chibanian hominins are transitional forms between H. erectus and modern H. sapiens and that Dali is the closest to modern H. sapiens. This raises the question, then, of who started to use “_H. daliensis_” as a species name. To the best of our knowledge, Dennis Etler8 may be the first researcher to mention H. daliensis. However, even in Etler’s paper, the name is used only once in a figure, and is never mentioned in the main text. It is unclear whether he intended to raise Dali to the species level. Although we do not know exactly what Etler was thinking when he included H. daliensis in his figure, it would seem that he may have simply been replacing “archaic _H. sapiens_” with a taxonomic name, more like a placeholder of sorts, something that is frequently seen in European and African Chibanian research. It should be noted that the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) has clear instructions on nomina that have been proposed conditionally: “A new name or nomenclatural act proposed conditionally and published after 1960 _is not thereby made available_” (ICZN 1999, p. 19; emphasis added). H. daliensis was never formally presented as a new species, and given current ICZN guidelines, it would seem the name is currently unavailable.

Another possible hominin nomen that has appeared is H. erectus mapaensis,9 based on of the important Maba cranial fossil. From a review of Woo and Peng’s10 original Maba paper, however, it would appear that the original analysts did not attempt to assign a species or even a subspecies name to the Maba specimen. Indeed, the last two sentences of the original paper read as follows: “The Maba hominin is an early archaic Homo sapiens fossil that fills a gap in our understanding of human evolution from H. erectus to archaic H. sapiens. This specimen is therefore a key piece of evidence for understanding this important transition in human evolution” (our translation from the original Chinese text). Thus, it would appear that Kurth9 may be the first person to mention H. erectus mapaensis, as he wrote, “perhaps H. e. mapaensis should be added as a later (end middle Pleistocene?) layer from the south” (our translation from the original German text). However, given the tentative proposed subspecies, it would suggest that H. erectus mapaensis should also be considered unavailable following ICZN guidelines.

Given the unavailability of H. daliensis and H. mapaensis, this raises the question as to what name(s) we should assign to the Chinese, and broader Asian, Chibanian hominin fossil record.

Taxonomic groupings

How many Chibanian hominin taxonomic groups are present in China? At a broad level, the phylogenetic analyses of Ni et al.6 showed that most of the Asian Middle Pleistocene hominins belong to a monophyletic group, suggesting that these hominins may be assigned to a single taxonomic group. However, given the growing range of morphological variation in the Asian Chibanian hominin fossil record, it is important to start to organize the fossils into different morphotypes as it is clear several different types are present. The proposed groupings depicted in Figure 1 are based on our knowledge of the record today.

Broadly speaking, at this moment, it would be better to keep Dali and Harbin separate, as there are no detailed comparative studies to justify lumping them. However, following further analyses, it may be possible Dali and Harbin could be assigned to the same taxon. If this occurs, then Dali should be assigned to the H. longi hypodigm. On the basis of comparative morphometrics, Jinniushan and Hualongdong may eventually be included in the H. longi hypodigm as well. Xujiayao and Xuchang, and on the basis of dentognathic comparisons Xiahe, Penghu, and the Denisovans, should be assigned to something else forthcoming, though Ni et al.6 may argue that Xiahe belongs in H. longi. The Maba and Narmada (Hathnora) crania have long been considered to be similar enough to be assigned to their own group as well. More detailed evaluation of these groupings is certainly warranted, though such analyses fall outside the scope of the current study. Regardless, it is clear that there is a growing range of variation in the Asian hominin fossil record. What role this record plays in broader debates is only beginning to be more fully understood.

Moving forward

The growing Chibanian hominin fossil record across Eurasia and Africa is raising a number of interesting questions related to its variability and how these different types are related to each other. In this regard, the Chinese fossil record plays a critical role in developing a better understanding of this debate. As part of these contributions from China, it is important to evaluate which hominin nomina are valid or not. It would appear that besides H. longi, there are probably at least two other types (Xujiayao/Xuchang and Maba) represented by the Chinese hominin fossil record. H. sapiens daliensis, H. daliensis, H. erectus mapaensis, and H. mapaensis are not available and should be removed from consideration.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 42372001.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published Online: October 20, 2023

Contributor Information

Christopher J. Bae, Email: cjbae@hawaii.edu.

Xijun Ni, Email: nixijun@ivpp.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Tattersall I. Species recognition in human paleontology. J. Hum. Evol. 1986;15:165–175. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stringer C. The status of Homo heidelbergensis (Schoetensack 1908) Evol. Anthropol. 2012;21:101–107. doi: 10.1002/evan.21311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rightmire G.P. Homo in the Middle Pleistocene: Hypodigms, variation, and species recognition. Evol. Anthropol. 2008;17:8–21. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roksandic M., Radović P., Wu X.-J., et al. Resolving the “muddle in the middle”: The case for Homo bodoensis sp. nov. Evol. Anthropol. Issues News Rev. 2022;20-29 doi: 10.1002/evan.21929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger L.R., Hawks J., de Ruiter D.J., et al. Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa. Elife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.09560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ni X., Ji Q., Wu W., et al. Massive cranium from Harbin in northeastern China establishes a new Middle Pleistocene human lineage. Innovation. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu X.Z. A well-preserved cranium of an archaic type of early Homo sapiens from Dali, China. Sci. Sin. 1981;24:530–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etler D.A. Homo erectus in East Asia: human ancestor or evolutionary dead-end? Gene. 2004;1992:2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurth . In: Menschliche Abstammtungslehre. Heberer G., editor. Fischer; 1965. Die homininen: Ein jeweilsbild nach dem Kenntnisstand von 1964; pp. 357–425. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woo J.-K., Peng R.-C. Fossil human skull of early Paleoanthropic stage found at Mapa, Shaokuan, Kwangtung Province. Palaeovert Palaeoanthropol. 1959;1:159–164. [Google Scholar]