Every Pakistani bank wants to dethrone Meezan Bank in Islamic banking. Who can succeed? - Profit by Pakistan Today (original) (raw)

When a financial institution in Pakistan thinks about its growth strategy, there is one play that every CEO ultimately reaches for: launching an Islamic finance business. And when it comes to Islamic finance in Pakistan, there is clearly one king: Meezan Bank, the undisputed market leader in the country and one that took the lead in 2003 – just one year after its launch in 2002 – and has never relinquished it since.

To move into the Islamic banking arena, therefore, means going head to head with Meezan Bank. No matter how strong or well-capitalised your balance sheet, or how well-regarded your name in the conventional market, the Islamic finance market is another beast entirely, and in this corner of Pakistan’s financial system, Meezan is a tough act to beat.

Yet over the last few years, we suspect that Irfan Siddiqui, the founding CEO of Meezan Bank, has been resting a little less than easy. Siddiqui is one of the savviest operators in the Pakistani banking market and he knows that – while most banks have struggled to compete with the franchise he has built – there are a few key competitors who are closing in. And if Meezan is not careful, it could lose its coveted slot as the leading Islamic bank in the country.

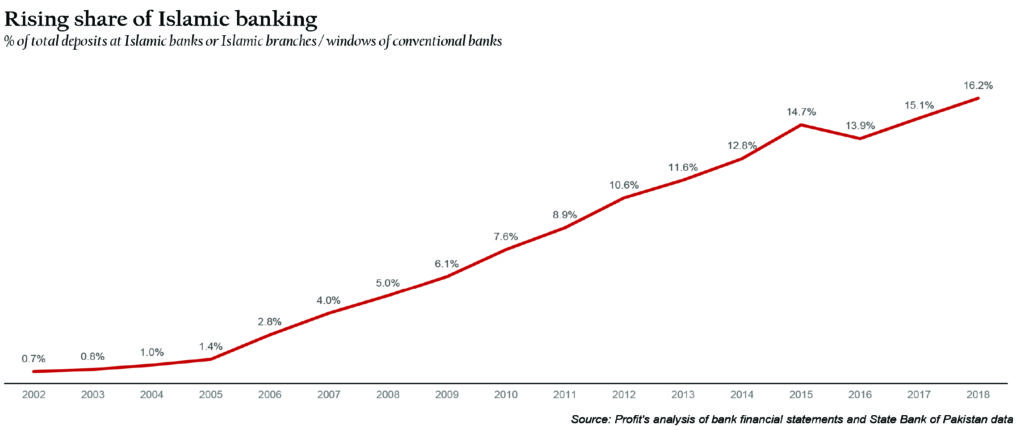

That is because Islamic finance is, quite simply, the hottest corner of the Pakistani financial markets. In 2002, the first full year of Meezan’s operations, there was only one other institution offering Islamic banking. In the 17 years since then, 20 more have joined the fray. At this point, there is only one bank left in Pakistan – JS Bank – that does not have an Islamic banking division and that is because it is a minority shareholder in BankIslami Pakistan.

The state of play in Islamic finance

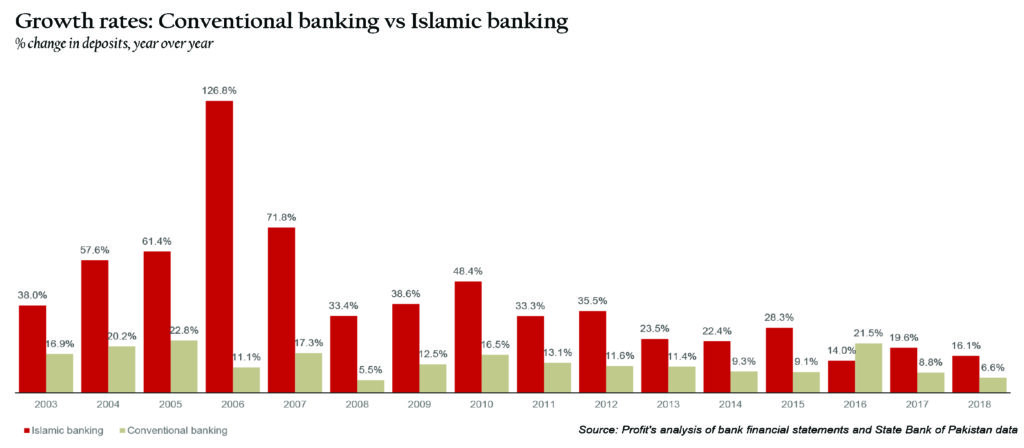

The reason why every bank CEO wants to jump into Islamic finance is simple enough: it is the fastest growing part of the Pakistani financial system. In the 15 years between 2003 and 2018, deposits in the conventional Pakistani banking system have grown at average rate of 20.2% per year, according to data from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), from Rs1,8 trillion to Rs13.4 trillion.

That number is impressive, until you take a look at the growth rate of the Islamic banking sector: during that same period, deposits at Islamic banks and Islamic banking windows of conventional banks grew at an average of 65.1% per year, from Rs14.4 billion to Rs2.2 trillion, according to _Profit_’s analysis of bank financial statements and State Bank data. Inflation during this period averaged 8.8% per year.

To understand the magnitude of just how much of a difference that divergence in growth rates can make, consider this fact: deposits in the conventional banking system are 6.3 times higher than they were 15 years ago. Islamic banking deposits in Pakistan are nearly 151 times higher over that same period.

In 2003, Islamic banking constituted just 0.8% of all banking deposits. At the end of 2018, that number stood at 16.2% of total deposits.

What makes this rise particularly attractive for the banks, however, is that it does not come at the expense of their conventional businesses.

“A significant portion of Islamic banking customers come from populations that were previously unbanked, thus creating a new revenue source for banks,” wrote Savina Joseph and Constantinos Kypreos, two analysts at Moody’s Investor Services, the global ratings agency, in a note issued to clients on Thursday, September 19, 2019.

In short, no bank can afford to not be in the Islamic finance business in Pakistan. The World Bank’s Findex database estimates that, as of 2017, 79% of Pakistani adults did not have a bank account. And given the fact that Pakistan’s population is 97% Muslim, a substantial proportion of people prefer to use Islamic banking systems for their financial needs.

While it is not possible to say with certainty what proportion of Pakistanis would prefer an Islamic bank over a conventional banking option, there are some revealed preferences of consumers visible in the data: for every new rupee that came into the banking system in Pakistan in 2018, about 30.3% went into the Islamic banking system and 69.7% went to the conventional system, according to _Profit_’s analysis of SBP and bank financial data.

How Meezan came to dominate the market

So how did Meezan comes to become the single biggest player in this market? Meezan’s single biggest advantage is being the first mover in the Islamic banking industry. In the late 1990s, there were two Islamic investment banks, both backed by Gulf Arab investors, operating in Pakistan: Meezan Investment Bank and Faysal Islamic Investment Bank. In 2002, both banks moved from being primarily corporate banks towards having a bigger retail presence, but only Meezan retained its Islamic identity. That decision appears to have been the difference that resulted in its significant outperformance.

Meezan Bank started its existence in 1997 as Al-Meezan Investment Bank, an institution with a limited licence to build up a corporate and investment banking franchise. At the time it started out, Al-Meezan Investment Bank was so small, and considered so insignificant, that it did not even have a full-time CEO.

Irfan Siddiqui, the man who was given the job (and still has it) was serving as general manager (effectively COO) of Pak-Kuwait Investment Company (PKIC), a joint venture between the governments of Pakistan and Kuwait.

Siddiqui continued in both capacities until at least 2001, working with a 30-person team to build out what appears to have been at the time a vehicle for PKIC’s fixed income business. However, it appears that Siddiqui saw the potential in Al-Meezan when nobody else appears to have spotted at the time.

Siddiqui started off his career as a chartered accountant in 1979, but worked for a significant portion of his career either in the Middle East or for Middle Eastern entities. The list of his previous employers includes the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, Abu Dhabi Investment Company, and the Kuwait Investment Authority. That exposure to the Persian Gulf Arab states appears to have given him both an appreciation for Islamic banking (Islamic finance originated in the GCC region) as well as a network of contacts that would later help him build up the business.

Soon after it was launched, Siddiqui used his old contacts to bring in several other investors into the bank including the Islamic Development Bank, the Saudi-Pak Industrial and Agricultural Investment Company (a joint venture between the governments of Pakistan and Saudi Arabia), Shamil Bank, a Bahraini bank owned by Dar al-Maal al-Islami (DMI) Trust (the sponsors of Faysal Bank), and the Kuwait Awqaf, a Kuwaiti state-owned endowment.

Meezan Bank’s current shareholding is now dominated by Noor Financial Investments Company, a publicly listed company in Kuwait that manages the wealth of several of that country’s richest families. Noor Financial owns 49% of the bank.

The challenge in those early years was that Pakistan at the time had no regulatory infrastructure in place for Islamic banking. Siddiqui and his team worked with the SBP to try to develop that set of rules, and was finally able to become the first Islamic bank licensed by the State Bank on January 31, 2001. That same day, Meezan Bank announced that would be acquiring the Pakistani branch network of French banking giant Société Générale, lending the bank the credibility of having bought the operations of a Western financial institution.

In the first full year of operation (2003), Meezan Bank had a hard time getting corporate clients to take it seriously as a bank. While it was able to get some of the larger, more reputable local corporates and a few of the multinationals to sign on to individual loans, it was not able to build a relationship with them in the way that conventional banks, with longer histories and easier to understand products, were able to get.

For its initial years, the bank relied on relationships with smaller and medium sized companies that had owners who were more religiously inclined. Many had never used a bank before because they believed that bank interest is prohibited under Islamic law, and so they did not mind not having the full suite of products available to them from the very beginning.

But even at the outset, Meezan Bank showed a desire to grow beyond just its core of Shariah-minded clients. To do that, it knew that it had to grow not just its own market share, but that of Islamic finance relative to conventional finance.

Its first mover advantage has meant that Meezan was always the largest player in the Islamic finance business, and so it – more than any other bank – could afford to invest in a full-time Islamic finance product development team that worked with religious scholars (including some who were on staff and others who were not) to build out the full set of products that would allow Islamic banks to compete for conventional business. To promote the industry as a whole, Meezan Bank has offered consulting services to other Islamic banks on how to create Shariah-compliant products.

The key, it turned out, was in the way the contracts were written. Meezan Bank, like every other Islamic financial institution, starts off with a conventional product and then looks for creative ways to rename, or in some cases, reconfigure, interest payments to make them smell Islamic. One of the favourite techniques used by such institutions is to give their products an Arabic name. So a car lease becomes Ijarah, a working capital loan for a manufacturing business becomes Murabaha, etc.

The Meezan juggernaut

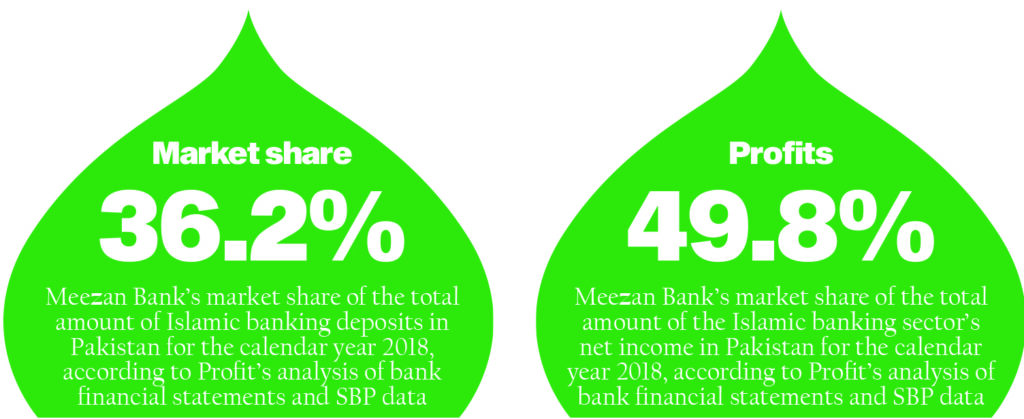

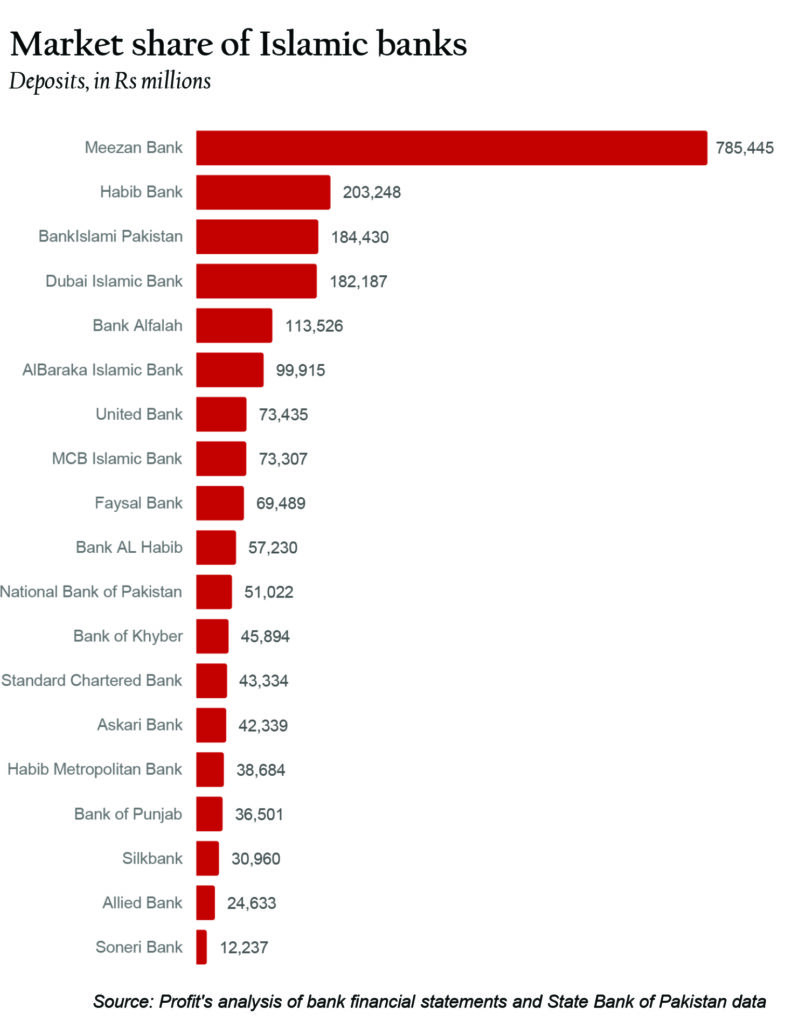

Over time, Meezan has been able to dominate the Islamic banking market in Pakistan and has never really let go of its status as the country’s leading Islamic bank, with a market share of just over 36.2% in 2018, a number that has remained largely steady over the past decade.

Over the past 10 years, Meezan’s deposits have grown at almost exactly the same rate as the Islamic banking market as a whole: an average growth rate of 27.3% per year for the past 10 years for Meezan versus an average of 27.6% for the Islamic banking market as a whole.

What is even more remarkable is the extent to which Meezan dominates profitability for the sector. According to _Profit_’s analysis of bank financial statements and SBP data, Meezan accounts for just under 50% of all profits made by any Islamic banking institution – whether it be a standalone Islamic bank or the Islamic banking branches and windows of conventional banks.

That dominance of the profits generated by the industry are then reflected in other measures of the financial health of the Islamic banking industry. Meezan Bank, for instance, had a return on equity of 23.8% in 2018, a year when the overall banking sector in Pakistan was only able to generate a meagre 10.5% return on equity. The rest of the Islamic banking industry – excluding Meezan – did even worse, with a 9.9% return on equity.

In fact, excluding Meezan, the Islamic banking industry’s return on equity has exceeded 10% only once over the past decade. This then begs the question: if you are not Meezan Bank, why even bother competing for the Islamic banking market? After all, what good is growth if it comes with a decade of meager returns?

The answer to that is somewhat more complicated than a simple yes or no. For instance, the Islamic banking industry’s net interest margin (the difference between the interest rate at which a banks lends out money and the interest rate it pays out on deposits) is somewhat higher than the banking industry as a whole.

For the year 2018, the net interest margin for the entire banking industry was 2.8% while the Islamic banking industry had a net interest margin of 3.2%. However, while it is true that Islamic banking institutions have a lower cost of deposits – their average cost comes to approximately 3.1% compared to 3.7% for the banking industry as a whole – they also lend at cheaper rates. In 2018, the average lending rate at Islamic banking institutions was 6.3% compared to 6.5% for all banks.

It is also often claimed that banks are chasing by diving head-first into the Islamic banking sector is the rapidly growing, cheap deposit base. They seem to be putting little thought into their ability to profitably lend out those deposits. Yet the reality is that Islamic banking institutions lend out 56.4% of their total assets as loans whereas Pakistan’s banks as a whole only lend out 43.4% of their assets as loans.

Part of this, of course, has to do with the fact that the government of Pakistan simply does not issue enough Islamic bonds, which limits the opportunities for Islamic banks to simply park their money in government bonds like the conventional banking industry is wont to do.

Nonetheless, being forced to lend out more of one’s balance sheet is not necessarily good for the banks, as reflected in their lower average lending rate.

The rising competitors in Islamic banking

Measured by return on equity – considered one of the most important measures of a bank’s profitability and broader financial health – the vast majority of Islamic banks and Islamic banking branches and windows of conventional banks pose very little threat to Meezan Bank.

_Profit_’s analysis of Pakistani banks’ financial statements reveals the following fact: over the past decade, only four banks – besides Meezan – have averaged returns on equity greater than 10%, and all four are the Islamic banking branches of conventional banks. The four banks are, in order of profitability: Habib Bank, Standard Chartered Bank, Bank AL Habib, and Bank Alfalah.

These four, however, pose a potentially formidable threat to Meezan Bank’s lead in this lucrative sector. Profit examines the strengths and weaknesses of each of these in turn.

Bank Alfalah: The weakest of the competitors is Bank Alfalah, whose Islamic banking division averages a return on equity of 12.6% per year for the past decade. By deposits, Alfalah is the fifth largest Islamic banking institution in the country. However, it grown relatively slowly compared to the industry average. Deposits have grown at an average of 14.1% per year for the past 10 years, compared to the industry’s 27.6% per year.

On the business front, while Bank Alfalah has among the cheapest costs of deposits, it has struggled to lend those deposits profitably and as a result has relatively middling net interest margin. Bank Alfalah’s Islamic banking branches have a net interest margin of 3.8%, according to _Profit_’s analysis of its financial statements.

After years of having invested in its Islamic banking franchise, it appears Bank Alfalah is willing to let its Shariah-compliant division flounder while it struggles to find the right strategy for growth for the bank as a whole.

Bank AL Habib: One of Pakistan’s “Three Banks Named Habib”, Bank AL Habib has one of the strongest balance sheets in the country’s entire banking sector. A key characteristic is the fact that Bank AL Habib tends to lend to clients with whom it has very old established relationships. As a result, the bank has the lowest non-performing loan ratio in the country.

Bank AL Habib’s deposits have been growing at an impressive average of 39.7% over the past 10 years. That might be chalked up to a low-base effect, except for the fact that both the bank’s three-year growth rate (averaging 57.2% per year) and five-year growth rate (averaging 46.0% per year) exceed its 10-year growth rate, suggesting that – far from slowing down – the bank is actually accelerating its pace of growth in this sector.

The bank’s net interest margin – at 2.9% – is lower than the Islamic banking industry average of 3.2%, but as stated earlier, Bank AL Habib more than makes up for it by having lower provisioning requirements for bad loans. As a result, the bank has been able to maintain an average return on equity of 15.9% for the past 10 years.

Standard Chartered Bank Pakistan: The very first bank in Pakistan to set up its Islamic banking branches and Islamic banking windows without converting fully to becoming an Islamic bank was Standard Chartered Bank Pakistan, when it first started its Shariah-compliant operations in 2004. The bank’s Islamic deposits have grown at a respectable average of 25.2% per year over the past 10 years, although recent growth has stalled, with 4-5% growth being more common.

Yet despite the recent spate of sluggish growth, Standard Chartered Saadiq, as its Islamic banking division is know, has considerable advantages. For instance, it has the highest net interest margin in the industry at 5.3%, driven largely by the fact that it has the lowest cost of deposits in the industry at 1.5%. How does Standard Chartered achieve this? Largely by offering some of the best financial technology among banks operating in Pakistan, which means that most of its clients use their StanChart accounts as their primary transaction accounts and hence maintain large balances in their zero-interest-paying current accounts.

That, combined with the fees StanChart is able to charge on ancillary services results in a much healthier revenue for the bank than any other bank might be able to achieve off a similar asset base. As a result, Standard Chartered Sadiq achieves returns on equity averaging 29.6% per year for the past 10 years.

Habib Bank: The largest bank in Pakistan is also the second-largest Islamic bank in the country and unquestionably the most formidable competitor for Meezan Bank. All of Meezan’s competitors are much smaller than it, and Habib Bank’s Islamic banking division is certainly no exception. But Habib is deploying the lethal combination of fast growth, low capital intensity of its expansion, and massive reach.

As stated earlier, many of the new clients who open accounts at an Islamic bank are the previously unbanked. Habib Bank’s advantage is the fact that it has the biggest physical branch network in the entire country, meaning it is closest to the majority of unbanked people in the country. Habib Bank’s Islamic banking net interest margin is not very high at just 2.4%, but is generating solid returns with very little equity deployed since it can simply open Islamic banking windows at its otherwise conventional branches.

Deposits have grown at an astronomically high 153% per year for the past 10 years though admittedly that is off a very low base. Over the past five years, deposits have grown at an average of 30.9% per year.

The also-rans of Islamic banking

It is a somewhat unusual fact that the four other dedicated Islamic banks in the country – BankIslami Pakistan, Dubai Islamic Bank, Albaraka Islamic Bank, and MCB Islamic Bank – barely merit a mention in an analysis of the country’s Islamic banking sector. That is because all four banks, while continuing to grow their deposit bases, have yet to manage their operations well.

All four have low net interest margins, high bad loan ratios, and as a result have low levels of profitability. And they continue to grow slower than both Meezan Bank as well as the Islamic banking branches of conventional banks, meaning they are actually losing market share.

The only want any of them would constitute a threat to Meezan is if all four merged to become one large Islamic bank. Perhaps then, the Meezan management will have to think of the other Islamic banks as their competitors.