Arcade: A Primer on the Python Game Framework (original) (raw)

Computer games are a great way to introduce people to coding and computer science. Since I was a player in my youth, the lure of writing video games was the reason I learned to code. Of course, when I learned Python, my first instinct was to write a Python game.

While Python makes learning to code more accessible for everyone, the choices for video game writing can be limited, especially if you want to write arcade games with great graphics and catchy sound effects. For many years, Python game programmers were limited to the pygame framework. Now, there’s another choice.

The arcade library is a modern Python framework for crafting games with compelling graphics and sound. Object-oriented and built for Python 3.6 and up, arcade provides the programmer with a modern set of tools for crafting great Python game experiences.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to:

- Install the

arcadelibrary - Draw items on the screen

- Work with the

arcadePython game loop - Manage on-screen graphic elements

- Handle user input

- Play sound effects and music

- Describe how Python game programming with

arcadediffers frompygame

This tutorial assumes you have an understanding of writing Python programs. Since arcade is an object-oriented library, you should also be familiar with object-oriented programming as well. All of the code, images, and sounds for this tutorial are available for download at the link below:

Background and Setup

The arcade library was written by Paul Vincent Craven, a computer science professor at Simpson College in Iowa, USA. As it’s built on top of the pyglet windowing and multimedia library, arcade features various improvements, modernizations, and enhancements over pygame:

- Boasts modern OpenGL graphics

- Supports Python 3 type hinting

- Has better support for animated sprites

- Incorporates consistent command, function, and parameter names

- Encourages separation of game logic from display code

- Requires less boilerplate code

- Maintains more documentation, including complete Python game examples

- Has a built-in physics engine for platform games

To install arcade and its dependencies, use the appropriate pip command:

On the Mac, you also need to install PyObjC:

Complete installation instructions based on your platform are available for Windows, Mac, Linux, and even Raspberry Pi. You can even install arcade directly from source if you’d prefer.

This tutorial assumes you’re using arcade 2.1 and Python 3.7 throughout.

Basic arcade Program

Before you dig in, let’s take a look at an arcade program that will open a window, fill it with white, and draw a blue circle in the middle:

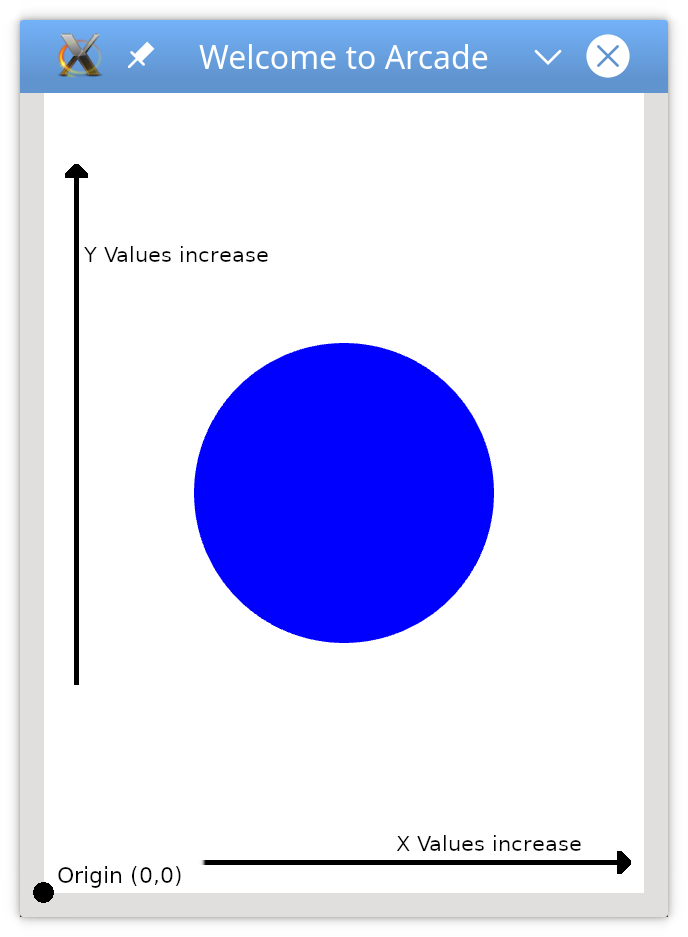

When you run this program, you’ll see a window that looks like this:

Let’s break this down line by line:

- Line 5 imports the

arcadelibrary. Without this, nothing else works. - Lines 8 to 11 define some constants you’ll use a little later, for clarity.

- Line 14 opens the main window. You provide the width, height, and title bar text, and

arcadedoes the rest. - Line 17 sets the background color using a constant from the

arcade.colorpackage. You can also specify an RGB color using a list or tuple. - Line 20 sets

arcadeinto drawing mode. Anything you draw after this line will be shown on the screen. - Lines 23 to 25 draw the circle by providing the center X and Y coordinates, the radius, and the color to use.

- Line 28 ends drawing mode.

- Line 31 displays your window for you to see.

If you’re familiar with pygame, then you’ll notice a few things are different:

- There is no

pygame.init(). All initialization is handled when you runimport arcade. - There is no explicitly-defined display loop. It’s handled in

arcade.run(). - There is no event loop here, either. Again,

arcade.run()handles events and provides some default behaviors, such as the ability to close the window. - You can use pre-defined colors for drawing rather than defining them all yourself.

- You have to start and finish drawing in arcade using

start_render()andfinish_render().

Let’s take a close look at the fundamental arcade concepts behind this program.

arcade Concepts

Like pygame, arcade code runs on almost every platform that supports Python. This requires arcade to deal with abstractions for various hardware differences on those platforms. Understanding these concepts and abstractions will help you design and develop your own games while understanding how arcade differs from pygame will help you adapt to its unique point of view.

Initialization

Since it deals with a variety of platforms, arcade must perform an initialization step before you can use it. This step is automatic and occurs whenever you import arcade, so there’s no additional code you need to write. When you import it, arcade does the following:

- Verify that you’re running on Python 3.6 or higher.

- Import the

pyglet_ffmeg2library for sound handling, if it’s available. - Import the

pygletlibrary for window and multimedia handling. - Set up constants for colors and key mappings.

- Import the remaining

arcadelibrary.

Contrast this with pygame, which requires a separate initialization step for each module.

Windows and Coordinates

Everything in arcade happens in a window, with you create using open_window(). Currently, arcade only supports a single display window. You can make the window resizable when you open it.

arcade uses the same Cartesian coordinate system you may have learned in algebra class. The window lives in quadrant I, with the origin point (0, 0) located in the lower-left corner of the screen. The x coordinate increases as you move right, and the y coordinate increases as you move up:

It’s important to note that this behavior is the opposite of pygame and many other Python game frameworks. It may take some time for you to adjust to this difference.

Drawing

Out of the box, arcade has functions for drawing various geometric shapes, including:

- Arcs

- Circles

- Ellipses

- Lines

- Parabolas

- Points

- Polygons

- Rectangles

- Triangles

All of the drawing functions begin with draw_ and follow a consistent naming and parameter pattern. There are different functions for drawing filled and outlined shapes:

Because rectangles are common, there are three separate functions for drawing them in different ways:

draw_rectangle()expects the x and y coordinates of the center of the rectangle, the width, and the height.draw_lrtb_rectangle()expects the left and right x coordinates, followed by the top and bottom y coordinates.draw_xywh_rectangle()uses the x and y coordinates of the bottom-left corner, followed by the width and the height.

Note that each function requires four parameters. You can also draw every shape using buffered drawing functions, which utilize vertex buffers to push everything directly to the graphics card for incredible performance improvements. All of the buffered drawing functions begin with create_ and follow consistent naming and parameter patterns.

Object-Oriented Design

At its core, arcade is an object-oriented library. Like pygame, you can write arcade code procedurally, as you did in the example above. However, the real power of arcade shows when you create completely object-oriented programs.

When you called arcade.open_window() in the example above, the code creates an arcade.Window object behind the scenes to manage that window. Later, you’ll create your own class based on arcade.Window to write a complete Python game.

First, take a look at the original example code, which now uses object-oriented concepts, to highlight the major differences:

Let’s take a look at this code line by line:

- Lines 1 to 11 are the same as the earlier procedural example.

- Line 15 is where the differences start. You define a class called

Welcomebased on the parent classarcade.Window. This allows you to override methods in the parent class as necessary. - Lines 18 to 26 define the .__init__() method. After calling the parent

.__init__()method using super() to set up the window, you set its background color, as you did before. - Lines 28 to 38 define

.on_draw(). This is one of severalWindowmethods you can override to customize the behavior of yourarcadeprogram. This method is called every timearcadewants to draw on the window. It starts with a call toarcade.start_render(), followed by all your drawing code. You don’t need to callarcade.finish_render(), however, asarcadewill call that implicitly when.on_draw()ends. - Lines 41 to 43 are your code’s main entry point. After you first create a new

Welcomeobject calledapp, you callarcade.run()to display the window.

This object-oriented example is the key to getting the most from arcade. One thing that you may have noticed was the description of .on_draw(). arcade will call this every time it wants to draw on the window. So, how does arcade know when to draw anything? Let’s take a look at the implications of this.

Game Loop

All of the action in pretty much every game occurs in a central game loop. You can even see examples of game loops in physical games like checkers, Old Maid, or baseball. The game loop begins after the game is set up and initialized, and it ends when the game does. Several things happen sequentially inside this loop. At a minimum, a game loop takes the following four actions:

- The program determines if the game is over. If so, then the loop ends.

- The user input is processed.

- The states of game objects are updated based on factors such as user input or time.

- The game displays visuals and plays sound effects based on the new state.

In pygame, you must set up and control this loop explicitly. In arcade, the Python game loop is provided for you, encapsulated in the arcade.run() call.

During the built-in game loop, arcade calls a set of Window methods to implement all of the functionality listed above. The names of these methods all begin with on_ and can be thought of as task or event handlers. When the arcade game loop needs to update the state of all Python game objects, it calls .on_update(). When it needs to check for mouse movement, it calls .on_mouse_motion().

By default, none of these methods do anything useful. When you create your own class based on arcade.Window, you override them as necessary to provide your own game functionality. Some of the methods provided include the following:

- Keyboard Input:

.on_key_press(),.on_key_release() - Mouse Input:

.on_mouse_press(),.on_mouse_release(),.on_mouse_motion() - Updating Game Object:

.on_update() - Drawing:

.on_draw()

You don’t need to override all of these methods, just the ones for which you want to provide different behavior. You also don’t need to worry about when they’re called, just what to do when they’re called. Next, you’ll explore how you can put all these concepts together to create a game.

Fundamentals of Python Game Design

Before you start writing any code, it’s always a good idea to have a design in place. Since you’ll be creating a Python game in this tutorial, you’ll design some gameplay for it as well:

- The game is a horizontally-scrolling enemy avoidance game.

- The player starts on the left side of the screen.

- The enemies enter at regular intervals and at random locations on the right.

- The enemies move left in a straight line until they are off the screen.

- The player can move left, right, up, or down to avoid the enemies.

- The player can’t move off the screen.

- The game ends when the player is hit by an enemy, or the user closes the window.

When he was describing software projects, a former colleague of mine once said, “You don’t know what you do until you know what you don’t do.” With that in mind, here are some things that you won’t cover in this tutorial:

- No multiple lives

- No scorekeeping

- No player attack capabilities

- No advancing levels

- No “Boss” characters

You’re free to try your hand at adding these and other features to your own program.

Imports and Constants

As with any arcade program, you’ll start by importing the library:

In addition to arcade, you also import random, as you’ll use random numbers later. The constants set up the window size and title, but what is SCALING? This constant is used to make the window, and the game objects in it, larger to compensate for high DPI screens. You’ll see it used in two places as the tutorial continues. You can change this value to suit the size of your screen.

Window Class

To take full advantage of the arcade Python game loop and event handlers, create a new class based on arcade.Window:

Your new class starts just like the object-oriented example above. On line 43, you define your constructor, which takes the width, height, and title of the game window, and use super() to pass those to the parent. Then you initialize some empty sprite lists on lines 49 through 51. In the next section, you’ll learn more about sprites and sprite lists.

Sprites and Sprite Lists

Your Python game design calls for a single player who starts on the left and can move freely around the window. It also calls for enemies (in other words, more than one) who appear randomly on the right and move to the left. While you could use the draw_ commands to draw the player and every enemy, it would quickly become difficult to keep it all straight.

Instead, most modern games use sprites to represent objects on the screen. Essentially, a sprite is a two-dimensional picture of a game object with a defined size that’s drawn at a specific position on the screen. In arcade, sprites are objects of class arcade.Sprite, and you’ll use them to represent your player as well as the enemies. You’ll even throw in some clouds to make the background more interesting.

Managing all these sprites can be a challenge. You’ll create a single-player sprite, but you’ll also be creating numerous enemies and cloud sprites. Keeping track of them all is a job for a sprite list. If you understand how Python lists work, then you’ve got the tools to use arcade’s sprite lists. Sprite lists do more than just hold onto all the sprites. They enable three important behaviors:

- You can update all the sprites in the list with a single call to

SpriteList.update(). - You can draw all the sprites in the list with a single call to

SpriteList.draw(). - You can check if a single sprite has collided with any sprite in the list.

You may wonder why you need three different sprite lists if you only need to manage multiple enemies and clouds. The reason is that each of the three different sprite lists exists because you use them for three different purposes:

- You use

.enemies_listto update the enemy positions and to check for collisions. - You use

.clouds_listto update the cloud positions. - Lastly, you use

.all_spritesto draw everything.

Now, a list is only as useful as the data it contains. Here’s how you populate your sprite lists:

You define .setup() to initialize the game to a known starting point. While you could do this in .__init__(), having a separate .setup() method is useful.

Imagine you want your Python game to have multiple levels, or your player to have multiple lives. Rather than restart the entire game by calling .__init__(), you call .setup() instead to reinitialize the game to a known starting point or set up a new level. Even though this Python game won’t have those features, setting up the structure makes it quicker to add them later.

After you set the background color on line 58, you then define the player sprite:

- Line 61 creates a new

arcade.Spriteobject by specifying the image to display and the scaling factor. It’s a good idea to organize your images into a single sub-folder, especially on larger projects. - Line 62 sets the y position of the sprite to half the height of the window.

- Line 63 sets the x position of the sprite by placing the left edge a few pixels away from the window’s left edge.

- Line 64 finally uses .append() to add the sprite to the

.all_spriteslist you’ll use for drawing.

Lines 62 and 63 show two different ways to position your sprite. Let’s take a closer look at all the sprite positioning options available.

Sprite Positioning

All sprites in arcade have a specific size and position in the window:

- The size, specified by

Sprite.widthandSprite.height, is determined by the graphic used when the sprite is created. - The position is initially set to have the center of the sprite, specified by

Sprite.center_xandSprite.center_y, at (0,0) in the window.

Once the .center_x and .center_y coordinates are known, arcade can use the size to calculate the Sprite.left, Sprite.right, Sprite.top, and Sprite.bottom edges as well.

This also works in reverse. For example, if you set Sprite.left to a given value, then arcade will recalculate the remaining position attributes as well. You can use any of them to locate the sprite or move it in the window. This is an extremely useful and powerful characteristic of arcade sprites. If you use them, then your Python game will require less code than pygame:

Now that you’ve defined the player sprite, you can work on the enemy sprites. The design calls for you to make enemy sprites appear at regular intervals. How can you do that?

Scheduling Functions

arcade.schedule() is designed exactly for this purpose. It takes two arguments:

- The name of the function to call

- The time interval to wait between each call, in seconds

Since you want both enemies and clouds to appear throughout the game, you set up one scheduled function to create new enemies, and a second to create new clouds. That code goes into .setup(). Here’s what that code looks like:

Now all you have to do is define self.add_enemy() and self.add_cloud().

Adding Enemies

From your Python game design, enemies have three key properties:

- They appear at random locations on the right side of the window.

- They move left in a straight line.

- They disappear when they go off the screen.

The code to create an enemy sprite is very similar to the code to create the player sprite:

.add_enemy() takes a single parameter, delta_time, which represents how much time has passed since the last time it was called. This is required by arcade.schedule(), and while you won’t use it here, it can be useful for applications that require advanced timing.

As with the player sprite, you first create a new arcade.Sprite with a picture and a scaling factor. You set the position using .left and .top to a random position somewhere off the screen to the right:

This allows the enemy to move onto the screen smoothly, rather than just appearing on the screen. Now, how do you make it move?

Moving Sprites

Moving a sprite requires you to change its position during the update phase of the game loop. While you can do this on your own, arcade has some built-in functionality to reduce your workload. Every arcade.Sprite not only has a set of position attributes, but it also has a set of motion attributes. Every time the sprite is updated, arcade will use the motion attributes to update the position, imparting relative motion to the sprite.

The Sprite.velocity attribute is a tuple consisting of the change in x and y positions. You can also access Sprite.change_x and Sprite.change_y directly. As mentioned above, every time the sprite is updated, its .position is changed based on the .velocity. All you need to do in .add_enemy() is set the velocity:

After you set the velocity to a random speed moving left on line 108, you add the new enemy to the appropriate lists. When you later call sprite.update(), arcade will handle the rest:

In your Python game design, enemies move in a straight line from right to left. Since your enemies are always moving left, once they’re off the screen, they’re not coming back. It would be good if you could get rid of an off-screen enemy sprite to free up memory and speed updates. Luckily, arcade has you covered.

Removing Sprites

Because your enemies are always moving left, their x positions are always getting smaller, and their y positions are always constant. Therefore, you can determine an enemy is off-screen when enemy.right is smaller than zero, which is the left edge of the window. Once you determine the enemy is off-screen, you call enemy.remove_from_sprite_lists() to remove it from all the lists to which it belongs and release that object from memory:

But when do you perform this check? Normally, this would happen right after the sprite moved. However, remember what was said earlier about the .all_enemies sprite list:

You use

.enemies_listto update the enemy positions and to check for collisions.

This means that in SpaceShooter.on_update(), you’ll call enemies_list.update() to handle the enemy movement automatically, which essentially does the following:

It would be nice if you could add the off-screen check directly to the enemy.update() call, and you can! Remember, arcade is an object-oriented library. This means you can create your own classes based on arcade classes, and override the methods you want to modify. In this case, you create a new class based on arcade.Sprite and override .update() only:

You define FlyingSprite as anything that will be flying in your game, like enemies and clouds. You then override .update(), first calling super().update() to process the motion properly. Then, you perform the off-screen check.

Since you have a new class, you’ll also need to make a small change to .add_enemy():

Rather than creating a new Sprite, you create a new FlyingSprite to take advantage of the new .update().

Adding Clouds

To make your Python game more appealing visually, you can add clouds to the sky. Clouds fly through the sky, just like your enemies, so you can create and move them in a similar fashion.

.add_cloud() follows the same pattern as .add_enemy(), although the random speed is slower:

Clouds move slower than enemies, so you calculate a lower random velocity on line 129.

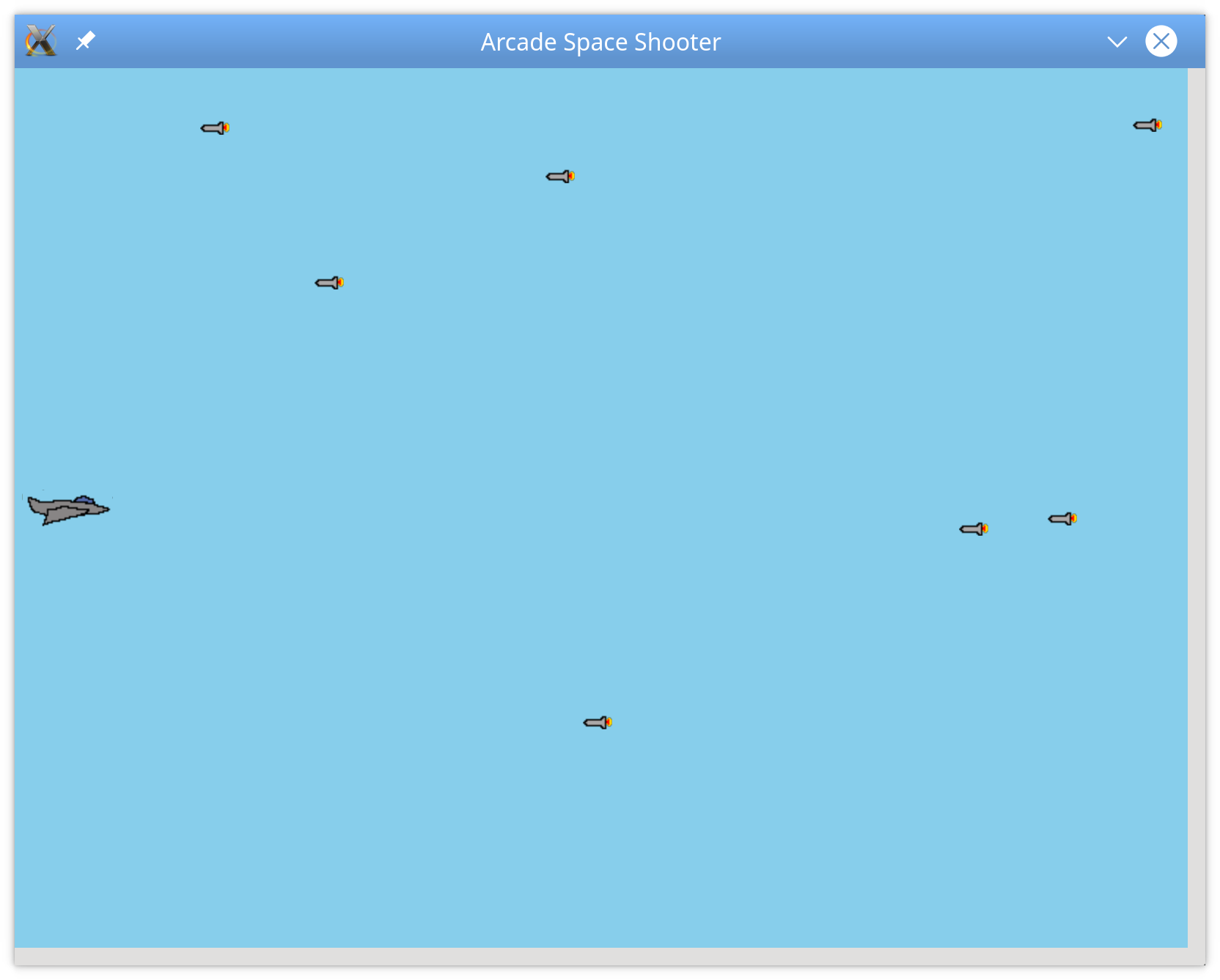

Now your Python game looks a bit more complete:

Your enemies and clouds are created and move on their own now. Time to make the player move as well using the keyboard.

Keyboard Input

The arcade.Window class has two functions for processing keyboard input. Your Python game will call .on_key_press() whenever a key is pressed and .on_key_release() whenever a key is released. Both functions accept two integer parameters:

symbolrepresents the actual key that was pressed or released.modifiersdenotes which modifiers were down. These include the Shift, Ctrl, and Alt keys.

Luckily, you don’t need to know which integers represent which keys. The arcade.key module contains all of the keyboard constants you might want to use. Traditionally, moving a player with the keyboard uses one or more of three different sets of keys:

- The four arrow keys for Up, Down, Left, and Right

- The keys I, J, K, and L, which map to Up, Left, Down, and Right

- For left-hand control, the keys W, A, S, and D, which also map to Up, Left, Down, and Right

For this game, you’ll use the arrows and I/J/K/L. Whenever the user presses a movement key, the player sprite moves in that direction. When the user releases a movement key, the sprite stops moving in that direction. You also provide a way to quit the game using Q, and a way to pause the game using P. To accomplish this, you need to respond to keypresses and releases:

- When a key is pressed, call

.on_key_press(). In that method, you check which key was pressed:- If it’s Q, then you simply quit the game.

- If it’s P, then you set a flag to indicate the game is paused.

- If it’s a movement key, then you set the player’s

.change_xor.change_yaccordingly. - If it’s any other key, then you ignore it.

- When a key is released, call

.on_key_release(). Again, you check which key was released:- If it’s a movement key, then you set the player’s

.change_xor.change_yto 0 accordingly. - If it’s any other key, then you ignore it.

- If it’s a movement key, then you set the player’s

Here’s what the code looks like:

In .on_key_release(), you only check for keys that will impact your player sprite movement. There’s no need to check if the Pause or Quit keys were released.

Now you can move around the screen and quit the game immediately:

You may be wondering how the pause functionality works. To see that in action, you first need to learn to update all your Python game objects.

Updating the Game Objects

Just because you’ve set a velocity on all your sprites doesn’t mean they will move. To make them move, you have to update them over and over again in the game loop.

Since arcade controls the Python game loop, it also controls when updates are needed by calling .on_update(). You can override this method to provide the proper behavior for your game, including game movement and other behavior. For this game, you need to do a few things to update everything properly:

- You check if the game is paused. If so, then you can just exit, so no further updates happen.

- You update all your sprites to make them move.

- You check if the player sprite has moved off-screen. If so, then simply move them back on screen.

That’s it for now. Here’s what this code looks like:

Line 198 is where you check if the game is paused, and simply return if so. That skips all the remaining code, so there will be no movement. All sprite movement is handled by line 202. This single line works for three reasons:

- Every sprite is a member of the

self.all_spriteslist. - The call to

self.all_sprites.update()results in calling.update()on every sprite in the list. - Every sprite in the list has

.velocity(consisting of the.change_xand.change_yattributes) and will process its own movement when its.update()is called.

Finally, you check if the player sprite is off-screen in lines 205 to 212 by comparing the edges of the sprites with the edges of the window. For example, on lines 205 and 206, if self.player.top is beyond the top of the screen, then you reset self.player.top to the top of the screen. Now that everything is updated, you can draw everything.

Drawing on the Window

Since updates to game objects happen in .on_update(), it seems appropriate that drawing the game objects would take place in a method called .on_draw(). Because you’ve organized everything into sprite lists, your code for this method is very short:

All drawing starts with the call to arcade.start_render() on line 234. Just like updating, you can draw all your sprites at once by simply calling self.all_sprites.draw() on line 235. Now there’s just one final part of your Python game to work on, and it’s the very last part of the initial design:

When the player is hit by an obstacle, or the user closes the window, the game ends.

This is the actual game part! Right now, enemies will fly through your player sprite doing nothing. Let’s see how you can add this functionality.

Collision Detection

Games are all about collisions of one form or another, even in non-computer games. Without real or virtual collisions, there would be no slap-shot hockey goals, no double-sixes in backgammon, and no way in chess to capture your opponent’s queen on the end of a knight fork.

Collision detection in computer games requires the programmer to detect if two game objects are partially occupying the same space on the screen. You use collision detection to shoot enemies, limit player movement with walls and floors, and provide obstacles to avoid. Depending on the game objects involved and the desired behavior, collision detection logic can require potentially complicated math.

However, you don’t have to write your own collision detection code with arcade. You can use one of three different Sprite methods to detect collisions quickly:

Sprite.collides_with_point((x,y))returnsTrueif the given point(x,y)is within the boundary of the current sprite, andFalseotherwise.Sprite.collides_with_sprite(Sprite)returnsTrueif the given sprite overlaps with the current sprite, andFalseotherwise.Sprite.collides_with_list(SpriteList)returns a list containing all the sprites in theSpriteListthat overlap with the current sprite. If there are no overlapping sprites, then the list will be empty, meaning it will have a length of zero.

Since you’re interested in whether or not the single-player sprite has collided with any of the enemy sprites, the last method is exactly what you need. You call self.player.collides_with_list(self.enemies_list) and check if the list it returns contains any sprites. If so, then you end the game.

So, where do you make this call? The best place is in .on_update(), just before you update the positions of everything:

Lines 202 and 203 check for a collision between the player and any sprite in .enemies_list. If the returned list contains any sprites, then that indicates a collision, and you can end the game. Now, why would you check before updating the positions of everything? Remember the sequence of action in the Python game loop:

- You update the states of the game objects. You do this in

.on_update(). - You draw all the game objects in their new positions. You do this in

.on_draw().

If you check for collisions after you update everything in .on_update(), then any new positions won’t be drawn if a collision is detected. You’re actually checking for a collision based on sprite positions that haven’t been shown to the user yet. It may appear to the player as though the game ended before there was an actual collision! When you check first, you ensure that what’s visible to the player is the same as the game state you’re checking.

Now you have a Python game that looks good and provides a challenge! Now you can add some extra features to help make your Python game stand out.

There are many more features you can add to your Python game to make it stand out. In addition to the features the game design called out that you didn’t implement, you may have others in mind as well. This section will cover two features that will give your Python game some added impact by adding sound effects and controlling the game speed.

Sound

Sound is an important part of any computer game. From explosions to enemy taunts to background music, your Python game is a little flat without sound. Out of the box, arcade provides support for WAV files. If the ffmpeg library is installed and available, then arcade also supports Ogg and MP3 format files. You’ll add three different sound effects and some background music:

- The first sound effect plays as the player moves up.

- The second sound effect plays when the player moves down.

- The third sound effect plays when there is a collision.

- The background music is the last thing you’ll add.

You’ll start with the sound effects.

Sound Effects

Before you can play any of these sounds, you have to load them. You do so in .setup():

Like your sprite images, it’s good practice to place all your sounds in a single sub-folder.

With the sounds loaded, you can play them at the appropriate time. For .move_up_sound and .move_down_sound, this happens during the .on_key_press() handler:

Now, whenever the player moves up or down, your Python game will play a sound.

The collision sound will play whenever .on_update() detects a collision:

Just before the window closes, a collision sound will play.

Background Music

Adding background music follows the same pattern as adding sound effects. The only difference is when it starts to play. For background music, you normally start it when the level starts, so load and start the sound in .setup():

Now, you not only have sound effects, but also some nifty background music as well!

Sound Limitations

There are some limitations on what arcade can currently do with sound:

- There is no volume control on any sounds.

- There is no way to repeat a sound, such as looping background music.

- There is no way to tell if a sound is currently playing before you try to stop it.

- Without

ffmpeg, you are limited to WAV sounds, which can be large.

Despite these limitations, it’s well worth the effort to add sound to your arcade Python game.

Python Game Speed

The speed of any game is dictated by its frame rate, which is the frequency at which the graphics on the screen are updated. Higher frame rates normally result in smoother gameplay, while lower frame rates give you more time to perform complex calculations.

The frame rate of an arcade Python game is managed by the game loop in arcade.run(). The Python game loop calls .on_update() and .on_draw() roughly 60 times per second. Therefore, the game has a frame rate of 60 frames per second or 60 FPS.

Notice the description above says that the frame rate is roughly 60 FPS. This frame rate is not guaranteed to be exact. It may fluctuate up or down based on many factors, such as load on the machine or longer-than-normal update times. As a Python game programmer, you want to ensure your Python game acts the same, whether it’s running at 60 FPS, 30 FPS, or any other rate. So how do you do this?

Time-Based Movement

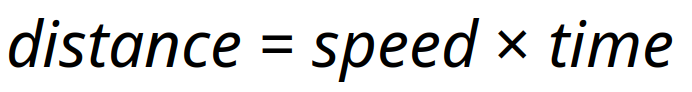

Imagine an object moving in space at 60 kilometers per minute. You can calculate how far the object will travel in any length of time by multiplying that time by the object’s speed:

The object moves 120 kilometers in 2 minutes and 30 kilometers in half a minute.

You can use this same calculation to move your sprites at a constant speed no matter what the frame rate. If you specify the sprite’s speed in terms of pixels per second, then you can calculate how many pixels it moves every frame if you know how much time has passed since the last frame appeared. How do you know that?

Recall that .on_update() takes a single parameter, delta_time. This is the amount of time in seconds that have passed since the last time .on_update() was called. For a game running at 60 FPS, delta_time will be 1/60 of a second or roughly 0.0167 seconds. If you multiply the time that’s passed by the amount a sprite will move, then you’ll ensure sprite movement is based on the time elapsed and not the frame rate.

Updating Sprite Movement

There’s just one problem—neither Sprite.on_update() nor SpriteList.on_update() accept the delta_time parameter. This means there’s no way to pass this on to your sprites to handle automatically. Therefore, to implement this feature, you need to update your sprite positions manually. Replace the call to self.all_sprites.update() in .on_update() with the following code:

In this new code, you modify the position of each sprite manually, multiplying .change_x and .change_y by delta_time. This ensures that the sprite moves a constant distance every second, rather than a constant distance every frame, which can smooth out gameplay.

Updating Sprite Parameters

Of course, this also means you should re-evaluate and adjust the initial position and speed of all your sprites as well. Recall the position and .velocity your enemy sprites are given when they’re created:

With the new movement calculations based on time, your enemies will now move at a maximum speed of 20 pixels every second. This means that on an 800-pixel-wide window, the fastest enemy will take forty seconds to fly across the screen. Further, if the enemy starts eighty pixels to the right of the window, then the fastest will take four full seconds just to appear!

Adjusting the position and velocity is part of making your Python game interesting and playable. Start by adjusting each by a factor of ten, and readjust from there. The same reevaluation and adjustments should be done with the clouds, as well as the movement velocity of the player.

Tweaks and Enhancements

During your Python game design, there were several features that you didn’t add. To add to that list, here are some additional enhancements and tweaks that you may have noticed during Python gameplay and testing:

- When the game is paused, enemies and clouds are still generated by the scheduled functions. This means that, when the game is unpaused, a huge wave of them are waiting for you. How do you prevent that from happening?

- As mentioned above, due to some limitations of the

arcadesound engine, the background music does not repeat itself. How do you work around that issue? - When the player collides with an enemy, the game ends abruptly without playing the collision sound. How do you keep the game open for a second or two before it closes the window?

There may be other tweaks you could add. Try to implement some of them as an exercise, and share your results down in the comments!

A Note on Sources

You may have noticed a comment when the background music was loaded, listing the source of the music and a link to the Creative Commons license. This was done because the creator of that sound requires it. The license requirements state that, in order to use the sound, both proper attribution and a link to the license must be provided.

Here are some sources for music, sound, and art that you can search for useful content:

- OpenGameArt.org: sounds, sound effects, sprites, and other artwork

- Kenney.nl: sounds, sound effects, sprites, and other artwork

- Gamer Art 2D: sprites and other artwork

- CC Mixter: sounds and sound effects

- Freesound: sounds and sound effects

As you make your games and use downloaded content such as art, music, or code from other sources, please be sure that you’re complying with the licensing terms of those sources.

Conclusion

Computer games are a great introduction to coding, and the arcade library is a great first step. Designed as a modern Python framework for crafting games, you can create compelling Python game experiences with great graphics and sound.

Throughout this tutorial, you learned how to:

- Install the

arcadelibrary - Draw items on the screen

- Work with the

arcadePython game loop - Manage on-screen graphic elements

- Handle user input

- Play sound effects and music

- Describe how Python game programming in

arcadediffers frompygame

I hope you give arcade a try. If you do, then please leave a comment below, and Happy Pythoning! You can download all the materials used in this tutorial at the link below: