Python's asyncio: A Hands-On Walkthrough (original) (raw)

by Leodanis Pozo Ramos Publication date Jul 30, 2025Reading time estimate 38m advanced python

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Hands-On Python 3 Concurrency With the asyncio Module

Python’s asyncio library enables you to write concurrent code using the async and await keywords. The core building blocks of async I/O in Python are awaitable objects—most often coroutines—that an event loop schedules and executes asynchronously. This programming model lets you efficiently manage multiple I/O-bound tasks within a single thread of execution.

In this tutorial, you’ll learn how Python asyncio works, how to define and run coroutines, and when to use asynchronous programming for better performance in applications that perform I/O-bound tasks.

By the end of this tutorial, you’ll understand that:

- Python’s

asyncioprovides a framework for writing single-threaded concurrent code using coroutines, event loops, and non-blocking I/O operations. - For I/O-bound tasks, async I/O can often outperform multithreading—especially when managing a large number of concurrent tasks—because it avoids the overhead of thread management.

- You should use

asynciowhen your application spends significant time waiting on I/O operations, such as network requests or file access, and you want to run many of these tasks concurrently without creating extra threads or processes.

Through hands-on examples, you’ll gain the practical skills to write efficient Python code using asyncio that scales gracefully with increasing I/O demands.

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “Python's asyncio: A Hands-On Walkthrough” quiz. You’ll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

A First Look at Async I/O

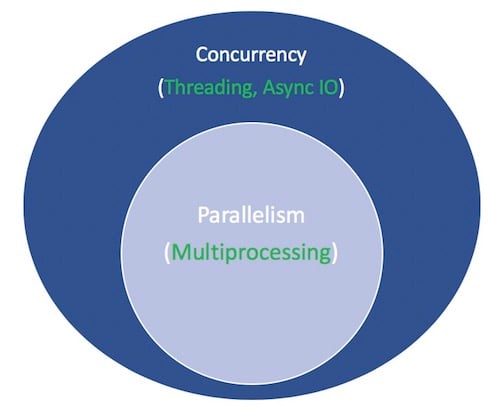

Before exploring asyncio, it’s worth taking a moment to compare async I/O with other concurrency models to see how it fits into Python’s broader, sometimes dizzying, landscape. Here are some essential concepts to start with:

- Parallelism consists of executing multiple operations at the same time.

- Multiprocessing is a means of achieving parallelism that entails spreading tasks over a computer’s central processing unit (CPU) cores. Multiprocessing is well-suited for CPU-bound tasks, such as tightly bound for loops and mathematical computations.

- Concurrency is a slightly broader term than parallelism, suggesting that multiple tasks have the ability to run in an overlapping manner. Concurrency doesn’t necessarily imply parallelism.

- Threading is a concurrent execution model in which multiple threads take turns executing tasks. A single process can contain multiple threads. Python’s relationship with threading is complicated due to the global interpreter lock (GIL), but that’s beyond the scope of this tutorial.

Threading is good for I/O-bound tasks. An I/O-bound job is dominated by a lot of waiting on input/output (I/O) to complete, while a CPU-bound task is characterized by the computer’s cores continually working hard from start to finish.

The Python standard library has offered longstanding support for these models through its multiprocessing, concurrent.futures, and threading packages.

Now it’s time to add a new member to the mix. In recent years, a separate model has been more comprehensively built into CPython: asynchronous I/O, commonly called async I/O. This model is enabled through the standard library’s asyncio package and the async and await keywords.

The asyncio package is billed by the Python documentation as a library to write concurrent code. However, async I/O isn’t threading or multiprocessing. It’s not built on top of either of these.

Async I/O is a single-threaded, single-process technique that uses cooperative multitasking. Async I/O gives a feeling of concurrency despite using a single thread in a single process. Coroutines—or coro for short—are a central feature of async I/O and can be scheduled concurrently, but they’re not inherently concurrent.

To reiterate, async I/O is a model of concurrent programming, but it’s not parallelism. It’s more closely aligned with threading than with multiprocessing, but it’s different from both and is a standalone member of the concurrency ecosystem.

That leaves one more term. What does it mean for something to be asynchronous? This isn’t a rigorous definition, but for the purposes of this tutorial, you can think of two key properties:

- Asynchronous routines can pause their execution while waiting for a result and allow other routines to run in the meantime.

- Asynchronous code facilitates the concurrent execution of tasks by coordinating asynchronous routines.

Here’s a diagram that puts it all together. The white terms represent concepts, and the green terms represent the ways they’re implemented:

Diagram Comparing Concurrency and Parallelism in Python (Threading, Async I/O, Multiprocessing)

For a thorough exploration of threading versus multiprocessing versus async I/O, pause here and check out the Speed Up Your Python Program With Concurrency tutorial. For now, you’ll focus on async I/O.

Async I/O Explained

Async I/O may seem counterintuitive and paradoxical at first. How does something that facilitates concurrent code use a single thread in a single CPU core? Miguel Grinberg’s PyCon talk explains everything quite beautifully:

Chess master Judit Polgár hosts a chess exhibition in which she plays multiple amateur players. She has two ways of conducting the exhibition: synchronously and asynchronously.

Assumptions:

- 24 opponents

- Judit makes each chess move in 5 seconds

- Opponents each take 55 seconds to make a move

- Games average 30 pair-moves (60 moves total)

Synchronous version: Judit plays one game at a time, never two at the same time, until the game is complete. Each game takes (55 + 5) * 30 == 1800 seconds, or 30 minutes. The entire exhibition takes 24 * 30 == 720 minutes, or 12 hours.

Asynchronous version: Judit moves from table to table, making one move at each table. She leaves the table and lets the opponent make their next move during the wait time. One move on all 24 games takes Judit 24 * 5 == 120 seconds, or 2 minutes. The entire exhibition is now cut down to 120 * 30 == 3600 seconds, or just 1 hour. (Source)

There’s only one Judit Polgár, who makes only one move at a time. Playing asynchronously cuts the exhibition time down from 12 hours to 1 hour. Async I/O applies this principle to programming. In async I/O, a program’s event loop—more on that later—runs multiple tasks, allowing each to take turns running at the optimal time.

Async I/O takes long-running functions—like a complete chess game in the example above—that would block a program’s execution (Judit Polgár’s time). It manages them in a way so other functions can run during that downtime. In the chess example, Judit Polgár plays with another participant while the previous ones make their moves.

Async I/O Isn’t Simple

Building durable multithreaded code can be challenging and prone to errors. Async I/O avoids some of the potential speed bumps you might encounter with a multithreaded design. However, that’s not to say that asynchronous programming is a simple task in Python.

Be aware that async programming can get tricky when you venture a bit below the surface level. Python’s async model is built around concepts such as callbacks, coroutines, events, transports, protocols, and futures—even just the terminology can be intimidating.

That said, the ecosystem around async programming in Python has improved significantly. The asyncio package has matured and now provides a stable API. Additionally, its documentation has received a considerable overhaul, and some high-quality resources on the subject have also emerged.

Async I/O in Python With asyncio

Now that you have some background on async I/O as a concurrency model, it’s time to explore Python’s implementation. Python’s asyncio package and its two related keywords, async and await, serve different purposes but come together to help you declare, build, execute, and manage asynchronous code.

Coroutines and Coroutine Functions

At the heart of async I/O is the concept of a coroutine, which is an object that can suspend its execution and resume it later. In the meantime, it can pass the control to an event loop, which can execute another coroutine. Coroutine objects result from calling a coroutine function, also known as an asynchronous function. You define one with the async def construct.

Before writing your first piece of asynchronous code, consider the following example that runs synchronously:

The count() function prints One and waits for a second, then prints Two and waits for another second. The loop in the main() function executes count() three times. Below, in the if __name__ == "__main__" condition, you take a snapshot of the current time at the beginning of the execution, call main(), compute the total time, and display it on the screen.

When you run this script, you’ll get the following output:

The script prints One and Two alternatively, taking a second between each printing operation. In total, it takes a bit more than six seconds to run.

If you update this script to use Python’s async I/O model, then it would look something like the following:

Now, you use the async keyword to turn count() into a coroutine function that prints One, waits for one second, then prints Two, and waits another second. You use the await keyword to await the execution of asyncio.sleep(). This gives the control back to the program’s event loop, saying: I will sleep for one second. Go ahead and run something else in the meantime.

The main() function is another coroutine function that uses asyncio.gather() to run three instances of count() concurrently. You use the asyncio.run() function to launch the event loop and execute main().

Compare the performance of this version to that of the synchronous version:

Thanks to the async I/O approach, the total execution time is just over two seconds instead of six, demonstrating the efficiency of asyncio for I/O-bound tasks.

While using time.sleep() and asyncio.sleep() may seem banal, they serve as stand-ins for time-intensive processes that involve wait time. A call to time.sleep() can represent a time-consuming blocking function call, while asyncio.sleep() is used to stand in for a non-blocking call that also takes some time to complete.

As you’ll see in the next section, the benefit of awaiting something, including asyncio.sleep(), is that the surrounding function can temporarily cede control to another function that’s more readily able to do something immediately. In contrast, time.sleep() or any other blocking call is incompatible with asynchronous Python code because it stops everything in its tracks for the duration of the sleep time.

The async and await Keywords

At this point, a more formal definition of async, await, and the coroutine functions they help you create is in order:

- The

async defsyntax construct introduces either a coroutine function or an asynchronous generator. - The

async withandasync forsyntax constructs introduce asynchronouswithstatements andforloops, respectively. - The

awaitkeyword suspends the execution of the surrounding coroutine and passes control back to the event loop.

To clarify the last point a bit, when Python encounters an await f() expression in the scope of a g() coroutine, await tells the event loop: suspend the execution of g() until the result of f() is returned. In the meantime, let something else run.

In code, that last bullet point looks roughly like the following:

There’s also a strict set of rules around when and how you can use async and await. These rules are helpful whether you’re still picking up the syntax or already have exposure to using async and await:

- Using the

async defconstruct, you can define a coroutine function. It may useawait,return, oryield, but all of these are optional:await,return, or both can be used in regular coroutine functions. To call a coroutine function, you must eitherawaitit to get its result or run it directly in an event loop.yieldused in anasync deffunction creates an asynchronous generator. To iterate over this generator, you can use an async for loop or a comprehension.async defmay not useyield from, which will raise a SyntaxError.

- Using

awaitoutside of anasync deffunction also raises aSyntaxError. You can only useawaitin the body of coroutines.

Here are some terse examples that summarize these rules:

Finally, when you use await f(), it’s required that f() be an object that’s awaitable, which is either another coroutine or an object defining an .__await__() special method that returns an iterator. For most purposes, you should only need to worry about coroutines.

Here’s a more elaborate example of how async I/O cuts down on wait time. Suppose you have a coroutine function called make_random() that keeps producing random integers in the range [0, 10] and returns when one of them exceeds a threshold. In the following example, you run this function asynchronously three times. To differentiate each call, you use colors:

The colorized output speaks louder than a thousand words. Here’s how this script is carried out:

This program defines the makerandom() coroutine and runs it concurrently with three different inputs. Most programs will consist of small, modular coroutines and a wrapper function that serves to chain each smaller coroutine. In main(), you gather the three tasks. The three calls to makerandom() are your pool of tasks.

While the random number generation in this example is a CPU-bound task, its impact is negligible. The asyncio.sleep() simulates an I/O-bound task and makes the point that only I/O-bound or non-blocking tasks benefit from the async I/O model.

The Async I/O Event Loop

In asynchronous programming, an event loop is like an infinite loop that monitors coroutines, takes feedback on what’s idle, and looks around for things that can be executed in the meantime. It’s able to wake up an idle coroutine when whatever that coroutine is waiting for becomes available.

The recommended way to start an event loop in modern Python is to use asyncio.run(). This function is responsible for getting the event loop, running tasks until they complete, and closing the loop. You can’t call this function when another async event loop is running in the same code.

You can also get an instance of the running loop with the get_running_loop() function:

If you need to interact with the event loop within a Python program, the above pattern is a good way to do it. The loop object supports introspection with .is_running() and .is_closed(). It can be useful when you want to schedule a callback by passing the loop as an argument, for example. Note that get_running_loop() raises a RuntimeError exception if there’s no running event loop.

What’s more important is understanding what goes on beneath the surface of the event loop. Here are a few points worth stressing:

- Coroutines don’t do much on their own until they’re tied to the event loop.

- By default, an async event loop runs in a single thread and on a single CPU core. In most

asyncioapplications, there will be only one event loop, typically in the main thread. Running multiple event loops in different threads is technically possible, but not commonly needed or recommended. - Event loops are pluggable. You can write your own implementation and have it run tasks just like the event loops provided in

asyncio.

Regarding the first point, if you have a coroutine that awaits others, then calling it in isolation has little effect:

In this example, calling main() directly returns a coroutine object that you can’t use in isolation. You need to use asyncio.run() to schedule the main() coroutine for execution on the event loop:

You typically wrap your main() coroutine in an asyncio.run() call. You can execute lower-level coroutines with await.

Finally, the fact that the event loop is pluggable means that you can use any working implementation of an event loop, and that’s unrelated to your structure of coroutines. The asyncio package ships with two different event loop implementations.

The default event loop implementation depends on your platform and Python version. For example, on Unix, the default is typically SelectorEventLoop, while Windows uses ProactorEventLoop for better subprocess and I/O support.

Third-party event loops are also available. For example, the uvloop package provides an alternative implementation that promises to be faster than the asyncio loops.

The asyncio REPL

Starting with Python 3.8, the asyncio module includes a specialized interactive shell known as the asyncio REPL. This environment allows you to use await directly at the top level, without wrapping your code in a call to asyncio.run(). This tool facilitates experimenting, debugging, and learning about asyncio in Python.

To start the REPL, you can run the following command:

Once you get the >>> prompt, you can start running asynchronous code there. Consider the example below, where you reuse the code from the previous section:

This example works the same as the one in the previous section. However, instead of running main() using asyncio.run(), you use await directly.

Common Async I/O Programming Patterns

Async I/O has its own set of possible programming patterns that allow you to write better asynchronous code. In practice, you can chain coroutines or use a queue of coroutines. You’ll learn how to use these two patterns in the following sections.

Coroutine Chaining

A key feature of coroutines is that you can chain them together. Remember, a coroutine is awaitable, so another coroutine can await it using the await keyword. This makes it easier to break your program into smaller, manageable, and reusable coroutines.

The example below simulates a two-step process that fetches information about a user. The first step fetches the user information, and the second step fetches their published posts:

In this example, you define two major coroutines: fetch_user() and fetch_posts(). Both simulate a network call with a random delay using asyncio.sleep().

In the fetch_user() coroutine, you return a mock user dictionary. In fetch_posts(), you use that dictionary to return a list of mock posts attributed to the user at hand. Random delays simulate real-world asynchronous behavior like network latency.

The coroutine chaining happens in the get_user_with_posts(). This coroutine awaits fetch_user() and stores the result in the user variable. Once the user information is available, it’s passed to fetch_posts() to retrieve the posts asynchronously.

In main(), you use asyncio.gather() to run the chained coroutines by executing get_user_with_posts() as many times as the number of user IDs you have.

Here’s the result of executing the script:

If you sum up the time of all the operations, then this example would take around 7.6 seconds with a synchronous implementation. However, with the asynchronous implementation, it only takes 2.68 seconds.

The pattern, consisting of awaiting one coroutine and passing its result into the next, creates a coroutine chain, where each step depends on the previous one. This example mimics a common async workflow where you get one piece of information and use it to get related data.

Coroutine and Queue Integration

The asyncio package provides a few queue-like classes that are designed to be similar to classes in the queue module. In the examples so far, you haven’t needed a queue structure. In chained.py, each task is performed by a coroutine, which you chain with others to pass data from one to the next.

An alternative approach is to use producers that add items to a queue. Each producer may add multiple items to the queue at staggered, random, and unannounced times. Then, a group of consumers pulls items from the queue as they show up, greedily and without waiting for any other signal.

In this design, there’s no chaining between producers and consumers. Consumers don’t know the number of producers, and vice versa.

It takes an individual producer or consumer a variable amount of time to add and remove items from the queue. The queue serves as a throughput that can communicate with the producers and consumers without them talking to each other directly.

A queue-based version of chained.py is shown below:

In this example, the producer() function asynchronously fetches mock user data. Each fetched user dictionary is placed into an asyncio.Queue object, which shares the data with consumers. After producing all user objects, the producer inserts a sentinel value—also known as a poison pill in this context—for each consumer to signal that no more data will be sent, allowing the consumers to shut down cleanly.

The consumer() function continuously reads from the queue. If it receives a user dictionary, it simulates fetching that user’s posts, waits a random delay, and prints the results. If it gets the sentinel value, then it breaks the loop and exits.

This decoupling allows multiple consumers to process users concurrently, even while the producer is still generating users, and the queue ensures safe and ordered communication between producers and consumers.

The queue is the communication point between the producers and consumers, enabling a scalable and responsive system.

Here’s how the code works in practice:

Again, the code runs in only 2.68 seconds, which is more efficient than a synchronous solution. The result is pretty much the same as when you used chained coroutines in the previous section.

Other Async I/O Features in Python

Python’s async I/O features extend beyond the async def and await constructs. They include other advanced tools that make asynchronous programming more expressive and consistent with regular Python constructs.

In the following sections, you’ll explore powerful async features, including async loops and comprehensions, the async with statement, and exception groups. These features will help you write cleaner, more readable asynchronous code.

Async Iterators, Loops, and Comprehensions

Apart from using async and await to create coroutines, Python also provides the async for construct to iterate over an asynchronous iterator. An asynchronous iterator allows you to iterate over asynchronously generated data. While the loop runs, it gives control back to the event loop so that other async tasks can run.

A natural extension of this concept is an asynchronous generator. Here’s an example that generates powers of two and uses them in a loop and comprehension:

There’s a crucial distinction between synchronous and asynchronous generators, loops, and comprehensions. Their asynchronous counterparts don’t inherently make iteration concurrent. Instead, they allow the event loop to run other tasks between iterations when you explicitly yield control by using await. The iteration itself is still sequential unless you introduce concurrency by using asyncio.gather().

Using async for and async with is only required when working with asynchronous iterators or context managers, where a regular for or with would raise errors.

Async with Statements

The with statement also has an asynchronous version, async with. This construct is quite common in async code, as many I/O-bound tasks involve setup and teardown phases.

For example, say you need to write a coroutine to check whether some websites are online. To do that, you can use aiohttp, which is a third-party library that you need to install by running python -m pip install aiohttp on your command line.

Here’s a quick example that implements the required functionality:

In this example, you use aiohttp and asyncio to perform concurrent HTTP GET requests to a list of websites. The check() coroutine fetches and prints the website’s status. The async with statement ensures that both ClientSession and the individual HTTP response are properly and asynchronously managed by opening and closing them without blocking the event loop.

In this example, using async with guarantees that the underlying network resources, including connections and sockets, are correctly released, even if an error occurs.

Finally, main() runs the check() coroutines concurrently, allowing you to fetch the URLs in parallel without waiting for one to finish before starting the next.

Other asyncio Tools

In addition to asyncio.run(), you’ve used a few other package-level functions, such as asyncio.gather() and asyncio.get_event_loop(). You can use asyncio.create_task() to schedule the execution of a coroutine object, followed by the usual call to the asyncio.run() function:

This pattern includes a subtle detail you need to be aware of: if you create tasks with create_task() but don’t await them or wrap them in gather(), and your main() coroutine finishes, then those manually created tasks will be canceled when the event loop ends. You must await all tasks you want to complete.

The create_task() function wraps an awaitable object into a higher-level Task object that’s scheduled to run concurrently on the event loop in the background. In contrast, awaiting a coroutine runs it immediately, pausing the execution of the caller until the awaited coroutine finishes.

The gather() function is meant to neatly put a collection of coroutines into a single future object. This object represents a placeholder for a result that’s initially unknown but will be available at some point, typically as the result of asynchronous computations.

If you await gather() and specify multiple tasks or coroutines, then the loop will wait for all the tasks to complete. The result of gather() will be a list of the results across the inputs:

You probably noticed that gather() waits for the entire result of the whole set of coroutines that you pass it. The order of results from gather() is deterministic and corresponds to the order of awaitables originally passed to it.

Alternatively, you can loop over asyncio.as_completed() to get tasks as they complete. The function returns a synchronous iterator that yields tasks as they finish. Below, the result of coro([3, 2, 1]) will be available before coro([10, 5, 2]) is complete, which wasn’t the case with the gather() function:

In this example, the main() function uses asyncio.as_completed(), which yields tasks in the order they complete, not in the order they were started. As the program loops through the tasks, it awaits them, allowing the results to be available immediately upon completion.

As a result, the faster task (task1) finishes first and its result is printed earlier, while the longer task (task2) completes and prints afterward. The as_completed() function is useful when you need to handle tasks dynamically as they finish, which improves responsiveness in concurrent workflows.

Async Exception Handling

Starting with Python 3.11, you can use the ExceptionGroup class to handle multiple unrelated exceptions that may occur concurrently. This is especially useful when running multiple coroutines that can raise different exceptions. Additionally, the new except* syntax helps you gracefully deal with several errors at once.

Here’s a quick demo of how to use this class in asynchronous code:

In this example, you have three coroutines that raise three different types of exceptions. In the main() function, you call gather() with the coroutines as arguments. You also set the return_exceptions argument to True so that you can grab the exceptions if they occur.

Next, you use a list comprehension to store the exceptions in a new list. If the list contains at least one exception, then you create an ExceptionGroup for them.

To handle this exception group, you can use the following code:

In this code, you wrap the call to asyncio.run() in a try block. Then, you use the except* syntax to catch the expected exception separately. In each case, you print an error message to the screen.

Async I/O in Context

Now that you’ve seen a healthy dose of asynchronous code, take a moment to step back and consider when async I/O is the ideal choice—and how to evaluate whether it’s the right fit or if another concurrency model might be better.

When to Use Async I/O

Using async def for functions that perform blocking operations—such as standard file I/O or synchronous network requests—will block the entire event loop, negate the benefits of async I/O, and potentially reduce your program’s efficiency. Only use async def functions for non-blocking operations.

The battle between async I/O and multiprocessing isn’t a real battle. You can use both models in concert if you want. In practice, multiprocessing should be the right choice if you have multiple CPU-bound tasks.

The contest between async I/O and threading is more direct. Threading isn’t simple, and even in cases where threading seems easy to implement, it can still lead to hard-to-trace bugs due to race conditions and memory usage, among other things.

Threading also tends to scale less elegantly than async I/O because threads are a system resource with a finite availability. Creating thousands of threads will fail on many machines or can slow down your code. In contrast, creating thousands of async I/O tasks is completely feasible.

Async I/O shines when you have multiple I/O-bound tasks that would otherwise be dominated by blocking wait time, such as:

- Network I/O, whether your program is acting as the server or the client

- Serverless designs, such as a peer-to-peer, multi-user network like a group chat

- Read/write operations where you want to mimic a fire-and-forget style approach without worrying about holding a lock on the resource

The biggest reason not to use async I/O is that await only supports a specific set of objects that define a particular set of methods. For example, if you want to do async read operations on a certain database management system (DBMS), then you’ll need to find a Python wrapper for that DBMS that supports the async and await syntax.

Libraries Supporting Async I/O

You’ll find several high-quality third-party libraries and frameworks that support or are built on top of asyncio in Python, including tools for web servers, databases, networking, testing, and more. Here are some of the most notable:

- Web frameworks:

- FastAPI: Modern async web framework for building web APIs.

- Starlette: Lightweight asynchronous server gateway interface (ASGI) framework for building high-performance async web apps.

- Sanic: Async web framework built for speed using

asyncio. - Quart: Async web microframework with the same API as Flask.

- Tornado: Performant web framework and asynchronous networking library.

- ASGI servers:

- Networking tools:

- aiohttp: HTTP client and server implementation using

asyncio. - HTTPX: Fully featured async and sync HTTP client.

- websockets: Library for building WebSocket servers and clients with

asyncio. - aiosmtplib: Async SMTP client for sending emails.

- aiohttp: HTTP client and server implementation using

- Database tools:

- Databases: Async database access layer compatible with SQLAlchemy core.

- Tortoise ORM: Lightweight async object-relational mapper (ORM).

- Gino: Async ORM built on SQLAlchemy core for PostgreSQL.

- Motor: Async MongoDB driver built on

asyncio.

- Utility libraries:

- aiofiles: Wraps Python’s file API for use with

asyncandawait. - aiocache: Async caching library supporting Redis and Memcached.

- APScheduler: A task scheduler with support for async jobs.

- pytest-asyncio: Adds support for testing async functions using pytest.

- aiofiles: Wraps Python’s file API for use with

These libraries and frameworks help you write performant async Python applications. Whether you’re building a web server, fetching data over the network, or accessing a database, asyncio tools like these give you the power to handle many tasks concurrently with minimal overhead.

Conclusion

You’ve gained a solid understanding of Python’s asyncio library and the async and await syntax, learning how asynchronous programming enables efficient management of multiple I/O-bound tasks within a single thread.

Along the way, you explored the differences between concurrency, parallelism, threading, multiprocessing, and asynchronous I/O. You also worked through practical examples using coroutines, event loops, chaining, and queue-based concurrency. On top of that, you learned about advanced asyncio features, including async context managers, async iterators, comprehensions, and how to leverage third-party async libraries.

Mastering asyncio is essential when building scalable network servers, web APIs, or applications that perform many simultaneous I/O-bound operations.

In this tutorial, you’ve learned how to:

- Distinguish between concurrency models and identify when to use

asynciofor I/O-bound tasks - Write, run, and chain coroutines using

async defandawait - Manage the event loop and schedule multiple tasks with

asyncio.run(),gather(), andcreate_task() - Implement async patterns like coroutine chaining and async queues for producer–consumer workflows

- Use advanced async features such as

async forandasync with, and integrate with third-party async libraries

With these skills, you’re ready to build high-performance, modern Python applications that can handle many operations asynchronously.

Frequently Asked Questions

Now that you have some experience with asyncio in Python, you can use the questions and answers below to check your understanding and recap what you’ve learned.

These FAQs are related to the most important concepts you’ve covered in this tutorial. Click the Show/Hide toggle beside each question to reveal the answer.

You use asyncio to write concurrent code with the async and await keywords, allowing you to efficiently manage multiple I/O-bound tasks in a single thread without blocking your program.

You typically get better performance from asyncio for I/O-bound work because it avoids the overhead and complexity of threads. This allows thousands of tasks to run concurrently without the limitations of Python’s GIL.

Use asyncio when your program spends a significant amount of time waiting on I/O-bound operations—such as network requests or file access—and you want to run many of these tasks concurrently and efficiently.

You define a coroutine using the async def syntax. To run it, either pass it to asyncio.run() or schedule it as a task with asyncio.create_task().

You rely on the event loop to manage the scheduling and execution of your coroutines, giving each one a chance to run whenever it awaits or completes an I/O-bound operation.

Take the Quiz: Test your knowledge with our interactive “Python's asyncio: A Hands-On Walkthrough” quiz. You’ll receive a score upon completion to help you track your learning progress:

Watch Now This tutorial has a related video course created by the Real Python team. Watch it together with the written tutorial to deepen your understanding: Hands-On Python 3 Concurrency With the asyncio Module