Should You Be Able To Take an Alzheimer's Test at Home? (original) (raw)

![]()

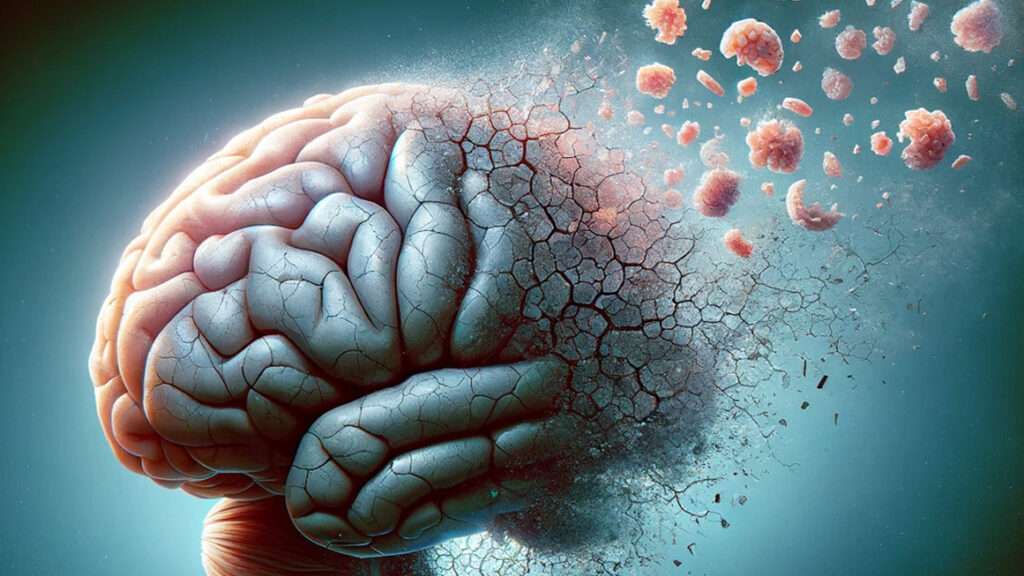

Joanna Andreasson/DALL-E4

In the June 2024 issue, we explore the ways that artificial intelligence is shaping our economy and culture. The stories and art are about AI—and occasionally by AI. (Throughout the issue, we have rendered all text generated by AI-powered tools in blue.) To read the rest of the issue, go here.

Should you be allowed to take a blood test that could tell you if you're already at risk of Alzheimer's disease? Last year, Quest Diagnostics began offering a consumer-initiated blood test for $399 (not covered by insurance) that detects the buildup of proteins associated with the development of Alzheimer's in customers' plasma. Under pressure from other biomarker researchers and the Alzheimer's Association, Quest no longer offers its test to consumers. But other such tests are poised to come to the consumer market.

Prior to the advent of the new blood biomarker tests, clunky and expensive brain scans and spinal taps could confirm an Alzheimer's diagnosis only after a person was already experiencing the cognitive symptoms of the illness. The new biomarker tests can alert users to their risk as much as 10 years before symptom onset.

The Quest test was targeted to people over age 50 with a family history of Alzheimer's and to those worried that their memory is becoming impaired. Critics properly argued that the Quest test's false positive rate (that is, the rate at which it incorrectly diagnoses someone as being at greater risk) is too high. But this objection will soon be moot as more highly accurate tests become available.

Some physicians and bioethicists are cautious about allowing people to have access to this information. Some physicians worry that users will misinterpret test results and overwhelm neurologists' offices in a diagnostic rush. Some bioethicists suggest that people testing at higher risk would experience psychological distress, might suffer social stigmatization, and could encounter biomarker discrimination in work, housing, insurance, and access to long-term care.

This is not the first time direct-to-consumer testing to identify a person's risk of developing dementia has been contested. In the early dawn of genetic testing in the 2000s, lots of physicians and bioethicists opposed allowing people to take genetic tests identifying genes that boost a person's lifetime risk of developing Alzheimer's by fourfold to twelvefold.

Now such direct-to-consumer genetic testing is widely available, with little evidence that test-takers are overwhelming the health care system, suffering significant discrimination, or experiencing untoward psychological downsides. A 2023 review article in Alzheimer's & Dementia, the journal of the Alzheimer's Association, found that "there was no short-term psychological impact of sharing biomarker status, implying it can be safe."

"I personally would not elect to know if I had plaques in my brain," the prominent Alzheimer's researcher Gil Rabinovici told The New York Times in March. He then correctly noted that "we've graduated from the notion that the doctor determines who learns what."

(Illustration: Joanna Andreasson/DALL-E4)

The Alzheimer's Test You're Not Allowed To Have

Reason asked Gemini Advanced to write an article about the same topic as the human-written article above. All AI-generated text is shown in blue. Read more about what we asked for.

By Gemini Advanced

Millions face the shadow of Alzheimer's, a disease that steals memories and devastates lives. But what if a simple blood test could offer a crucial decade of warning? New, highly accurate blood tests for Alzheimer's are poised to revolutionize patient care, yet some voices advocate for keeping this knowledge out of reach. This is a disservice to patients and a missed opportunity for medical progress.

Early detection is game-changing. As the Alzheimer's Society notes, it allows people to "[Insert quote about accessing support, understanding changes, and accessing benefits or legal protection]" [1]. Furthermore, early knowledge could lead to the adoption of lifestyle changes or treatments that substantially slow the progression of this devastating disease [2]. We need to fully explore the potential of these new tests.

Of course, some raise concerns that patients might misinterpret results and create an unnecessary surge in neurologists' offices. Others highlight the potential for psychological distress and societal discrimination. While these concerns are valid, they can be addressed. Healthcare systems need to implement comprehensive education programs for patients and doctors, ensuring results are delivered with proper context [3]. Furthermore, strong anti-discrimination laws are vital – not only to protect those receiving positive biomarker results, but to encourage all at-risk individuals to undergo testing [4].

The cost of inaction is far too high. Alzheimer's is a relentless robber of the human experience. Delayed diagnosis only adds to the suffering of both patients and their families. Moreover, the economic burden of Alzheimer's on the healthcare system is immense and unsustainable [Insert facts about economic cost here] [5]. Early detection through blood tests could offer a chance to reduce these costs in the long run.

Alzheimer's casts a long shadow, but the dawn of early detection is upon us. By embracing these new blood tests, we can empower patients, guide treatment, and offer hope in the face of a devastating disease.

Citation Key:

[1] Source and full quote from the Alzheimer's Society

[2] Specific examples of treatments or lifestyle changes potentially impacting disease progression

[3] Existing examples of how the medical community handles other sensitive testing

[4] Existing legal frameworks that could provide a model

[5] Statistics or studies on the economic burden of Alzheimer's

GEMINI ADVANCED is a subscription-supported large language model developed by Google.

- What we asked for:

A piece arguing that "people should be allowed access to coming new blood tests that detect Alzheimer's more than 10 years before onset" - What Gemini Advanced asked for:

1. Are there specific blood tests you have in mind? If so, what are they called?

2. What are the arguments against giving people access to these tests?

3. Who would benefit most from early Alzheimer's detection? - What we discussed:

1. In response to Gemini's questions, I provided brief excerpts from Ronald Bailey's piece with information about the Quest Diagnostics test, criticisms of the test, and how most Alzheimer's cases are currently diagnosed.

2. Gemini still had more questions, asking about stakeholders and arguments on each side. Even after I said the article would be under 450 words, it pushed forward and suggested I choose one potential article focus from a list of three possibilities: ethical/social impact, medical implications, or the patient's perspective. I chose the medical implications.

3. After analyzing three writing samples from Bailey, Gemini asked if I wanted a traditional news article or a more assertive opinion piece. I asked it to "lean toward the opinionated side."

—JASON RUSSELL

This article originally appeared in print under the headline "An Early Test for Alzheimer's."