Tropical Sprue: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology (original) (raw)

Overview

Background

Tropical sprue (TS) is a syndrome characterized by acute or chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and malabsorption of nutrients. It occurs in residents of or visitors to the tropics and subtropics, and it may be caused by environmental factors. [1] The first description of tropical sprue is attributed to William Hillary's 1759 account of his observations of chronic diarrhea while in Barbados. Subsequently, tropical sprue was described in tropical climates throughout the world. The definition has been expanded to include malabsorption of at least two different substances when other causes are excluded.

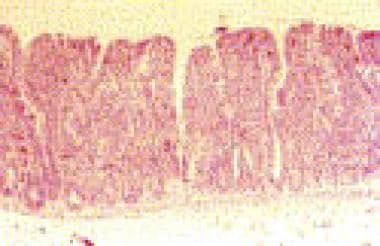

Tropical Sprue. Tropical sprue (hematoxylin-eosin [H&E], original magnification ×10).

Tropical Sprue. Endoscopic views of unsuspected celiac disease. A: Absent duodenal folds. B: Mucosal fissures and scalloped folds. C: Scalloped fold.

The exact causative factor of tropical sprue is unknown, but an intestinal microbial infection is believed to be the initiating insult. The infection results in enterocyte injury, intestinal stasis, and possible bacteria overgrowth. Villous destruction and demonstrable nutrient malabsorption occur in varying degrees. Folate, vitamin B-12, and iron deficiencies are the most common nutrient deficiencies.

Patient education

Travelers to the tropics should be aware of this syndrome and take steps to limit exposure to enteric pathogens. If protracted diarrhea occurs, early presentation to medical personnel is helpful.

For patient education resources, see the Digestive Disorders Center, as well as Diarrhea, Traveler's (Traveler's Diarrhea).

Pathophysiology

The exact role of microbial agents in the initiation and propagation of the disease is poorly understood. [1] One theory is that an acute intestinal infection leads to jejunal and ileal mucosa injury; then intestinal bacterial overgrowth and increased plasma enteroglucagon results in retardation of small-intestinal transit. Central to this process is folate deficiency, which probably contributes to further mucosal injury.

Hormone enteroglucagon and motilin levels are elevated in patients with tropical sprue. Enterocyte injury can cause these elevations. Enteroglucagon causes intestinal stasis, but the role of motilin is not clear.

The upper small intestine is predominantly affected; however, because it is a progressive and contiguous disease, the distal small intestine up to the terminal ileum may be involved. Pathological changes are rarely demonstrated in the stomach and colon. Coliform bacteria, such as Klebsiella, E coli and Enterobacter species are isolated and are the usual organisms associated with tropical sprue. [2, 3, 4, 5]

Epidemiology

Tropical sprue appears to be declining globally. [6]

United States data

Tropical sprue occurs in geographically limited areas. The syndrome is not reported in US patients unless they have lived in or traveled to any of the areas described below.

International data

Tropical sprue occurs in both epidemic and endemic forms, primarily in Southeast Asia and the Caribbean. The actual prevalence of the endemic form is difficult to estimate, but rates as high as 8% are reported in Puerto Rico. One unusual feature is that tropical sprue appears to be limited to certain geographic areas, even within the tropics. For example, although tropical sprue is commonly reported in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, it is not reported in Jamaica. Only a few cases are reported in emigrants from southern Africa.

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

Tropical sprue is confined to geographic regions, but it is observed in individuals of all races who live in or visit those regions.

The male-to-female ratio is equal.

Tropical sprue is primarily an adult disease, but it has been described in children.

Prognosis

Prognosis is generally good for patients with tropical sprue.

Morbidity/mortality

Acute illness complicated by fluid and electrolyte deficits is rarely fatal. The frequency of this complication is not known but appears to be decreasing. Chronic illness with severe malabsorption and anemia can lead to death, but this usually occurs in patients with comorbid conditions.

Complications

Complications of tropical sprue include anemia, malnutrition, and vitamin deficiency.

- Louis-Auguste J, Kelly P. Tropical enteropathies. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017 Jul. 19 (7):29. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Gray, GM. Tropical Sprue. Blaser,MJ, Smith, PD, Ravdin, JI. Infections of the Gastrointestinal Tract. New York: Raven Press; 1995. 333.

- Klipstein, FA. Tropical Sprue. Gastroenterology. 1968. 54:275.

- Gorbach, SL, Banwell, JG, Jacobs, B, et al. Tropical Sprue and Malnutrition in West Bengal. I. Intestinal microflora and absorption. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1970. 23:1545.

- Klipstein, FA, Holdeman, LV, Corcino, JJ, et al. Enterotoxigenic intestinal bacteria in tropical sprue. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1973. 79:632.

- Sharma P, Baloda V, Gahlot GP, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histological differentiation between celiac disease and tropical sprue: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jan. 34 (1):74-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Brown IS, Bettington A, Bettington M, et al. Tropical sprue: revisiting an underrecognized disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014 May. 38(5):666-72. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ghoshal UC, Mehrotra M, Kumar S, et al. Spectrum of malabsorption syndrome among adults & factors differentiating celiac disease & tropical malabsorption. Indian J Med Res. 2012 Sep. 136(3):451-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Ritchie BK, Brewster DR, Davidson GP, Tran CD, et al. 13C-sucrose breath test: novel use of a noninvasive biomarker of environmental gut health. Pediatrics. 2009 Aug. 124(2):620-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Green PH, Shane E, Rotterdam H, Forde KA, Grossbard L. Significance of unsuspected celiac disease detected at endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000 Jan. 51(1):60-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lo A, Guelrud M, Essenfeld H, Bonis P. Classification of villous atrophy with enhanced magnification endoscopy in patients with celiac disease and tropical sprue. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007 Aug. 66(2):377-82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Cook GC. Aetiology and pathogenesis of postinfective tropical malabsorption (tropical sprue). Lancet. 1984 Mar 31. 1(8379):721-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dutta AK, Chacko A, Avinash B. Suboptimal performance of IgG anti-tissue transglutaminase in the diagnosis of celiac disease in a tropical country. Dig Dis Sci. 2009 Mar 31. epub ahead of print. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Evans KE, Leeds JS, Sanders DS. Be vigilant for patients with coeliac disease. Practitioner. 2009 Oct. 253(1722):19-22, 2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Farthing MJ. Tropical malabsorption and tropical diarrhea. Feldman M, ed. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1998. 1574-84.

- Floch MH, Ozick L. Tropical sprue. In: Hurst JW, ed. Medicine for the Practicing Physician. 3rd ed. Boston, Mass: Butterworth. 1992:1547-1549.

- French AB. Tropical sprue--specific disease or extreme of a spectrum?. Ann Intern Med. 1968 Jun. 68(6):1362-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gilman AG, ed. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 8th ed. New York, NY:. Pergamon Press Inc. 1990.

- Greeberger NJ, Isselbacher KJ. Disorders of absorption. Fauci AS, ed. Harrison's Principle of Internal Medicine. 14th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1998. 1626.

- Klipstein FA. Tropical sprue in travelers and expatriates living abroad. Gastroenterology. 1981 Mar. 80(3):590-600. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Klipstein FA. Tropical sprue--an iceberg disease?. Ann Intern Med. 1967 Mar. 66(3):622-3. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Klipstein FA, Baker SJ. Regarding the definition of tropical sprue. Gastroenterology. 1970 May. 58(5):717-21. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kuhlmann FM, Weil GJ. Infectious risks for travelers to the tropics. Mo Med. 2009 Jul-Aug. 106(4):263-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nath SK. Tropical sprue. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005 Oct. 7(5):343-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Thielman NM, Guerrant RL. Persistent diarrhea in the returned traveler. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1998 Jun. 12(2):489-501. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Toskes P. Malabsorption. Bennet JC, Plum F, eds. Cecil's Textbook of Medicine. 20th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1996. 705-6.

- Ghoshal UC, Gwee KA. Post-infectious IBS, tropical sprue and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: the missing link. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jul. 14 (7):435-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tropical Sprue. Subtotal villous atrophy (hematoxylin-eosin [H&E], original magnification ×10).

- Tropical Sprue. Tropical sprue (hematoxylin-eosin [H&E], original magnification ×10).

- Tropical Sprue. Endoscopic views of unsuspected celiac disease. A: Absent duodenal folds. B: Mucosal fissures and scalloped folds. C: Scalloped fold.

Author

Coauthor(s)

Sabo B Tanimu, MD Fellow, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Harlem Hospital Center

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Oluyinka S Adediji, MD, MBBS Consulting Staff, Department of Adult and General Medicine, Health Services Incorporated, Montgomery, Alabama

Oluyinka S Adediji, MD, MBBS is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Physicians, American Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Specialty Editor Board

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Received salary from Medscape for employment. for: Medscape.

Chief Editor

Burt Cagir, MD, FACS Associate Regional Dean and Professor of Surgery, Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine; Director, General Surgery Residency Program, Executive Director, Donald Guthrie Foundation for Research and Education, Guthrie Robert Packer Hospital; Medical Director, Guthrie/RPH Skills and Simulation Lab; Associate in Surgery, Guthrie Robert Packer Hospital and Corning Hospital

Burt Cagir, MD, FACS is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Surgeons, Association of Program Directors in Surgery, Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Additional Contributors

Manoop S Bhutani, MD Professor, Co-Director, Center for Endoscopic Research, Training and Innovation (CERTAIN), Director, Center for Endoscopic Ultrasound, Department of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, University of Texas Medical Branch; Director, Endoscopic Research and Development, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

Manoop S Bhutani, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Association for the Advancement of Science, American College of Gastroenterology, American College of Physicians, American Gastroenterological Association, American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.