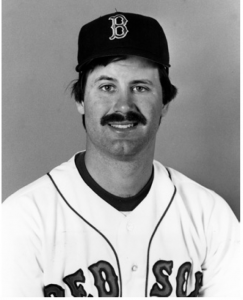

Mike Stenhouse – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

The son of an All-Star, a two-time All-American at Harvard University, and a first-round draft pick, Mike Stenhouse seemed destined to thrive in the majors. But in a five-year career with three teams that never saw him play in more than half the schedule, Stenhouse never hit. While he did not make the postseason roster for the 1986 Boston Red Sox, the best and last major-league squad he played for, Stenhouse did have one important plate appearance that season that sparked the Red Sox to an extra-inning win over a division rival.

The son of an All-Star, a two-time All-American at Harvard University, and a first-round draft pick, Mike Stenhouse seemed destined to thrive in the majors. But in a five-year career with three teams that never saw him play in more than half the schedule, Stenhouse never hit. While he did not make the postseason roster for the 1986 Boston Red Sox, the best and last major-league squad he played for, Stenhouse did have one important plate appearance that season that sparked the Red Sox to an extra-inning win over a division rival.

Mike’s father, Dave, began his minor-league career in 1955. In 1958 he began the season with the Pueblo (Colorado) Bruins, an affiliate of the Chicago Cubs. In Pueblo, Dave’s wife, Phyllis (DeBiasio) Stenhouse, gave birth to Mike on May 29, 1958. As of August 2015, Dave and Phyllis had been married for more than 58 years.

Dave went just 16-28 as a Washington Senators pitcher for three years, but improbably started the second 1962 All-Star Game as a 28-year-old rookie. After baseball, Dave worked in the insurance business and co-founded the Insurance Center, a financial planning company. In 1968 he was named baseball coach at Rhode Island College, winning more than 200 games in 12 years. In 1980 he was named baseball coach at Brown University and held that post for 10 years.1

Mike’s mother, Phyllis, a fellow student of Dave’s at the University of Rhode Island, earned a master’s in teaching and worked as a librarian at a junior high school in Cranston, Rhode Island.

Mike grew up in Cranston although he first played on a team in Honolulu when Dave pitched for the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League. Mike’s “ascent toward professional baseball began early. Mike was 9 … when Dave Stenhouse left professional baseball and built a batting cage in the backyard of the family home. … [Dave was always willing to throw — at full speed, he said — from the distance at which they would face their peers.”2

Mike wanted to be like Dave. “My father told me just about all there is about baseball,” he said.3 “He loved it when he was up there, so it’s always been one of my dreams to play in the majors.”4

After carefully considering Brown University and Harvard University, Mike entered Harvard, an incubator of more Cabinet members than cleanup hitters.5 He put up staggering offensive numbers that would help him realize his dream. As a freshman facing Northeastern University, Stenhouse “a) went five for six at the plate, b) hit for the cycle and added an extra single and sacrifice fly to boot, c) scored four runs and drove in six, and d) popped up in the ninth. That last one was simply to show that nobody’s perfect.”6

Stenhouse “hit .475 and knocked in 40 runs … as a freshman. Both are Harvard records, but believe it or not, underscore the fact that [he is unconquerable by anything short of a frontal lobotomy once he stands in at the plate. Another couple of seasons like the one past for the big guy and he can forget about graduate school.”7

At Harvard, Stenhouse set school records that still stood long after the conclusion of his Crimson career, for homers in a season (10 in 1978), batting average in a season (.475 in 1977), career triples (12), and lifetime batting average (.422). As of 2015 he ranked second in homers with 19, behind someone who played four years for Harvard as opposed to Stenhouse’s three.8

Not only did Stenhouse make All-American twice, but he also, like his dad, played college basketball. Mike played key roles in two close games that went down to the final seconds. Against the University of Connecticut, Harvard trailed by one with seven seconds left but had a one-and-one situation at the foul line. The player who drew the foul got hurt, so Stenhouse had to shoot instead. He missed, and Harvard lost by one.9

Stenhouse redeemed himself against an Ivy rival as Harvard edged Dartmouth College thanks to “supersub Mike Stenhouse’s 17-foot jumper with two seconds left. Stenhouse capped a hustling Crimson rally by snaring a loose ball … taking two quick dribbles and sticking a jump shot over two falling Dartmouth defenders … to give Harvard its first lead of the game.”10

Stenhouse averaged 4.1 points per game for the 1977-78 Crimson. His teammate Charlie Baker averaged only 1.7 points before going onto political prominence as the governor of Massachusetts.11

Stenhouse, after again earning All-American honors as a sophomore, started to receive attention from “several scouts, [who] say that [he] is such a good hitter [that] he could go in the top five picks in the country next June.”12 The rest of Stenhouse’s game proved more problematic. “There is, however, much doubt about Stenhouse’s foot speed and also about whether he can be a major league fielder. ‘Terrible’ was one scout’s assessment of Stenhouse’s running ability. ‘He’s strictly an American League prospect, because that’s where the DH is.’”13

After breaking his hand in a Cape Cod League game between his sophomore and junior seasons, Stenhouse chose not to play basketball before his junior year, a decision he later saw as “a mistake,” adding, “I lost some rhythm, and the Seattle Mariners had considered drafting me with the first overall pick before taking some guy named [Al] Chambers instead. The only teams I did not want to draft me were Cleveland and Oakland, and Oakland picked me with the last pick of the first round, just before Seattle would have taken me with the first pick of the second round.”14 Said Stenhouse after the selection, “My father and I have to do some talking with the A’s to see if we can reach a reasonable agreement.”15

Oakland Athletics owner Charlie Finley did not always act in a conventionally reasonable fashion. Baseball writer Peter Gammons, who liked to tout New England baseball players generally and spent years hyping Stenhouse specifically, wrote, “The kid I feel sorry for is … Mike Stenhouse. … His father gets one call within the necessary 15 days from … Finley, and … [eventually] they come to terms for $12,000 and a guarantee to be brought up in September, but when it comes to signing, Finley reneged and wouldn’t put his September offer in writing.”16

Stenhouse characterized the discussions as “really ridiculous.” He said, “I knew what I was looking for was not that unreasonable, moneywise and everything-wise. I wasn’t looking for six figures. What they were offering was barely two figures.”17

A little more than seven months after the A’s picked and failed to sign Stenhouse, the Montreal Expos drafted him fourth overall in a secondary draft for previously picked players.18 Jim Fanning, Montreal’s vice president and director of player development, was enthusiastic about Stenhouse’s prospects, saying, “We’ll develop his skills, and hopefully we’ll make a major-league player out of him.”19

Although the Expos signed him for more than the A’s had offered him, Stenhouse saw his decision to reject Oakland as a second mistake since “the A’s had been unloading talent, and Montreal had Hall of Famers or All-Stars at every position I played.”

Stenhouse began his pro career in 1980 with the Single-A West Palm Beach Expos. Early in the season Stenhouse went all Babe Herman and singled into a triple play: “Wayne Simmons singled to open the top of the fifth and Wally Johnson drew a walk. … Stenhouse ripped a hit to right field, scoring Simmons. Johnson was tagged out between third and home, and Stenhouse was caught and run down between first and second.”20 An appeal resulted in the umpire calling out Simmons for missing third base.

Montreal promoted Stenhouse to the Memphis Chicks of the Double-A Southern League, where he played in one game in 1980. He spent the entire 1981 season in Memphis after getting hit on the forearm with the Expos during spring training.21

In 1982 Stenhouse made the jump to the Triple-A Wichita Aeros, where he debuted with a hit, two walks, a stolen base, and two runs scored.22 After a banner season in which he smashed 25 homers and drew more than 100 walks, Stenhouse got the call to the majors and played in the final game of the 1982 season, the last one in Willie Stargell’s Hall of Fame career. “After not swinging a bat for weeks,” Stenhouse struck out as a pinch-hitter against Pittsburgh’s Don Robinson. Stenhouse had good company in becoming the second of four batters in a row fanned by Robinson, as he followed Andre Dawson and preceded Gary Carter and Tim Wallach.

Back at Wichita, Stenhouse got off to a sizzling start in 1983, batting a league-leading .393 through May 27 and finishing with a .355 average, 25 homers for the second straight year, and a 1.172 OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging average). Numbers like these caused the Expos to recall Stenhouse in July, but Montreal had no real spot for him even though manager Bill Virdon had said he would play regularly if called up.”23 First baseman Al Oliver would hit .300, and the Expos had a regular outfield of Tim Raines, Dawson, and Warren Cromartie, none of whom had yet turned 30.

On July 28, 1983, Stenhouse made his season debut batting for the light-hitting Doug Flynn in game one of a doubleheader against the Cardinals. With one out and runners on first and second in a tie game, he pinch-hit against closer Bruce Sutter. “I had never really seen a forkball,” recalled Stenhouse, “but I knew I should swing if it was up. Sutter’s first pitch was a mistake right down the middle of the plate but slower in velocity than I imagined it would be. I was early on it and cued it off of the rounded end of the bat, something that happens only every few years. I fouled it off and knew I would never get another pitch like that. Then he threw another high forkball, and I did the exact same thing, except this time the ball stayed fair, but I barely got out of the batter’s box because I did not know where the ball was.” St. Louis turned a 5-4-3 double play on what Stenhouse eventually characterized as “the most embarrassing play of my career.”

In the nightcap, Stenhouse had his first major-league hit, a double off Bob Forsch.

On August 4 Stenhouse got his first major-league RBI with a single off Ed Lynch of the Mets. But overall he struggled, batting .160 in his first 11 games with the Expos, and went back to Wichita, where he was voted the American Association’s Most Valuable Player.24

Peter Gammons continued to promote Stenhouse, listing him 24th among the top nonpitching rookies of 1984. Gammons enthused about Stenhouse that “the former Harvard star can swing the bat … he works hard … and he hustles. No matter what the reports say, this guy is probably going to hit and end up the left fielder.”25

Stenhouse had a monster spring training that seemed to justify Gammons’s glorifications. Making Gammons look reserved, a Florida sportswriter wrote, “If Mike Stenhouse continues to hit the way he has this spring, he’ll set records that Babe Ruth, Roger Maris and Hank Aaron never dreamed about.”26

Stenhouse had his opening in 1984 with the free agent Cromartie having gone to Japan and Oliver playing in San Francisco after a trade. Montreal had signed Pete Rose as a free agent, star-struck by his historic career rather than his dismal 1983 season when at the age of 42 he had slugged a sickening .286 with a dismal OPS of .602. Gammons thought the lineup had room for both players, reporting that “the Expos are beginning to change their thinking and are pondering having Pete Rose move to first to make room for Harvardian Mike Stenhouse, who is hitting nearly .450 [in spring training] and fills their vital need for a lefthanded bat.”27

With his hot spring start, Stenhouse certainly had self-confidence: “I have nothing left to prove in Triple A. I can play in the major leagues. I can help this team.”28

Indeed, a young left-handed 1B/OF who had a sparkling college career with a father who starred in the American League would help the 1984 Expos. Unfortunately for Stenhouse, Terry Francona filled that role and batted .346 in 58 games. Montreal unwisely still gave Rose more than 300 plate appearances. At the age of 43, he improved his numbers slightly but insufficiently, slugging .295 with a .629 OPS.

Stenhouse did not even make the team at first following “an 0-for-22 drought”29 and “temporarily quit … when the Expos optioned him to Indianapolis,”30 which had replaced Wichita as the top minor-league affiliate of Montreal.

Stenhouse would play just 27 games for Indianapolis and continued to destroy Triple-A pitching, highlighted by a May 10 game in which he homered three times and drove in eight runs.31

Back with the Expos, Stenhouse hit his first major-league homers in 1984. His first came on May 23 on a “fastball from Andy Hawkins. Pete Rose was the first guy to congratulate me. He was a really good friend back then.”

His second home run represented his fondest baseball memory because it reminded him of the camaraderie of his teammates. On July 14 Montreal faced Cincinnati’s Mario Soto, who came into the game with a 9-2 record. Stenhouse recalled, “Soto had the nastiest changeup. You couldn’t tell the difference between that and his fastball. But Rose said Soto had a tell when pitching from the stretch. If he brings his glove down facing you, he’ll throw a fastball. If the back of the glove is facing you, then he’ll throw a changeup.” With two runners on in the bottom of the first, Stenhouse forgot about the tell but managed to single and drive in a run. Expecting congratulations back in the dugout after the inning, Stenhouse instead got a hard time for missing the tell. In the third inning with a runner on and two out, Stenhouse remembered to look, got a fastball from Soto, and homered, sparking the Expos to a 6-2 win.

The homers notwithstanding, in 80 games at Montreal, Stenhouse put up Rose-like numbers, slugging .297 with a .586 OPS. The Expos in 1984 had a losing record for the first time since 1978. Virdon was fired on August 30. After the season, Montreal fan Stan Michne contributed a commentary to The Bill James Baseball Abstract 1985 alleging “Virdon deserved to get fired on the basis of his handling of Stenhouse alone.”32

To replace Virdon, Montreal reportedly considered Tim McCarver, Chuck Tanner, and Earl Weaver. Pittsburgh still had Tanner under contract so could require compensation to allow him to go to a division rival, and the Pittsburgh Press reported that Stenhouse might go to the Pirates.33 Stenhouse’s future in Montreal seemed short. He decided to play winter ball in the Dominican Republic “so someone could see me, and I could get traded.”34

On January 9, 1985, the Expos granted Stenhouse his wish, trading him to the Twins for pitcher Jack O’Connor. According to the hyperbolic Gammons, “Few players have ever been happier about being traded than Harvardian Stenhouse, of Rhode Island’s first family of baseball. ‘I’d been hoping for a deal just to get some chance to play. … I’d really gotten to the point where I had to move on.’”35

On promise alone, Stenhouse should have played more than Rose did in 1984, but Stenhouse failed to produce for a struggling team. He made excuses: “The way I was used in Montreal — very much part-time — you find yourself going to the plate and trying to hit a six-run home run so they will keep you in the lineup. It was impossible for me to play that way. … Admittedly, the Montreal park was a little big for me. I left a lot of long fly balls on the warning track.”36

The record shows, however, that the Expos gave Stenhouse more than 200 plate appearances at positions than demanded offense that season, and he hit just .183. Olympic Stadium may have hurt his extra-base power, but he hit all four of his National League homers there and twice as many as he ever hit in any other park. In three Montreal seasons, Stenhouse had an ugly .273/.269/.542 slash line that neither argued for more at-bats nor augured well for his future.

Minnesota offered a fresh start thanks to “Manager Billy Gardner … who pushed for the acquisition of the lefthanded-hitting Stenhouse. … Gardner thinks Stenhouse can provide lefthanded power to a Twins’ lineup that — beyond Kent Hrbek — is severely lacking in lefties.”37

In 1985 Stenhouse struggled but still had his best offensive season with career highs in every major offensive category except for doubles and OBP. The Twins had lost 10 straight coming into a June 2 game against the Milwaukee Brewers and trailed 4-3 with one on and two out in the bottom of the eighth. Milwaukee pitcher Bob Gibson threw Stenhouse “a slider, probably down out of the strike zone, but I was a lowball hitter.” Stenhouse’s two-run homer gave Minnesota a streak-busting 5-4 win.

On July 9 against Baltimore, Stenhouse smashed one through the box against rookie Nate Snell, breaking his rib, sending him to the hospital for an overnight stay, and putting him on the disabled list.38 In the first game of a doubleheader on August 31 against future Red Sox teammate Steve Crawford in the ninth inning with two on, two out, and Minnesota trailing Boston 5-4, “Crawford was only one strike away from sealing the victory with … a 2-2 count on Mike Stenhouse, who hadn’t driven in a run since Aug. 8.”39 Stenhouse went the other way with a single to tie the game, which the Twins won two batters later on a Ron Washington single.

Stenhouse said he had fond memories of his year in Minneapolis, where he met his first wife, but regretted that he did not play more with Minnesota unexpectedly using Greg Gagne at shortstop and Roy Smalley at designated hitter more than originally anticipated. “For all intents and purposes, that was the end of my career right there,” Stenhouse concluded 30 years later. “I was feeling good and then my chance to play again went away. I never felt comfortable at the plate again.”

On December 12, 1985, Minnesota traded Stenhouse to his hometown Red Sox. “General manager Lou Gorman, a Rhode Island guy who knew my dad well, got me to replace the retired Rick Miller as a left-handed-hitting outfielder/designated hitter,” Stenhouse said. In exchange, the Twins received pitcher Charlie Mitchell, who never returned to the majors. “Every kid who grows up in New England dreams of playing in Fenway,” Stenhouse said. “I’m happy to get that opportunity.”40

By this point, however, even Gammons, Stenhouse’s biggest media fan for more than seven years, seemed underwhelmed, concluding that the deal, “if nothing else, makes [Boston] better read.”41

Somewhat more optimistically, Bill James wrote that Boston “picked up Mike Stenhouse cheap, and you know I like Stenhouse, while of course his chance of making it in the big leagues now isn’t half of what it was a couple of years ago.”42

Stenhouse started the 1986 season as he had in 1984. Again, he had a superb spring (“Ted Williams worked with me in spring training, which did not make [Red Sox hitting coach] Walt Hriniak happy”), failed to make the team, and balked at reporting to the minors. After initially refusing to speak to the media following his demotion, Stenhouse unloaded the following day: “I certainly earned a position and I didn’t get it. When you don’t get something you earned, you think maybe it wasn’t there to get in the first place. … I’m not criticizing anything. I’m just wondering why they got me in the first place. … The thing that bothers me is thinking whether the whole thing was a sham or not.”43

As injudicious as his words seem on paper, Stenhouse probably did not feel better after the player Boston kept over Stenhouse — catcher Dave Sax — spent more than one month with the team without appearing in a single game. Ominously, the Sox recalled Stenhouse because “Bill Buckner says his sore elbow isn’t improving.”44

Stenhouse had the biggest moment of his Boston career on June 10, 1986. Facing Toronto’s Mark Eichhorn (Stenhouse remembered that “he threw side-arm slop, changeups and sliders”) in the top of the 10th inning with two outs and the bases loaded in a 3-3 tie, Stenhouse drew a pinch-hit walk to drive in the winning run in a 4-3 final. “To go in for [Marty] Barrett … is amazing,” Stenhouse said. “But to tell you the truth, it relaxed me.”45

Stenhouse claimed that Barrett “walked halfway to the plate, turned around, and said to [manager John] McNamara, ‘I can’t hit Eichorn, Mac, hit Stenny for me.’ It was a close 3-and-2 pitch, but I knew it was down and away.”

The plate discipline of Stenhouse earned him an odd nickname in the Red Sox clubhouse when “his teammates … started calling him ‘Sony.’ That’s Sony as in Walkman. Stenhouse has walked six times in 12 pinch-hit appearances.”46

The major-league career of Mike Stenhouse ended a little more than six weeks later on July 23, 1986. Facing Jay Howell, Stenhouse grounded out to end a 9-2 loss against Oakland, Boston’s fourth straight defeat. The Red Sox decided to replace him with Mike Greenwell. Dan Shaughnessy wrote, “Stenhouse, another lefty hitter, had a disappointing stint in Boston.”47

Boston tried to re-sign Stenhouse, but he chose to ink a minor-league contract with Detroit on February 4, 1987. Lou Gorman conceded that “he didn’t get a lot of chances,” but added, “with players like him, you’ve got to produce when you get the chance, and he didn’t. We think he had major-league ability and offered him another contract, but he chose to go elsewhere.”48

Nate Snell, whose career Stenhouse had inadvertently derailed, had signed a similar deal with the Tigers two days earlier. Snell did play for Detroit in 1987, but Stenhouse did not after suffering “the worst injury of my career in spring training. On a cool morning BP session I strained a side muscle and then ripped it taking a swing in a game later that day.”

At the end of his pro career, Stenhouse had a more realistic self-assessment as a classic Four-A player: one who could excel in the minors but could not stay in the majors. “You can play well in Triple-A ball over and over. That doesn’t necessarily prove anything.”49

Stenhouse played exceptionally well in Triple A from 1982 through 1984 with his low OPS a robust .949. With Pawtucket in 1986 and Toledo in 1987, however, Stenhouse posted consecutive OPS marks of .820. Having turned 29 in May 1987, Stenhouse turned down minor-league offers and ended his professional career after the 1987 season, returning to Rhode Island with his pregnant wife.

At first, he became an executive search consultant. “I went from the dugout to the corporate board room,” quipped Stenhouse. Still, at first he dabbled in the game, “developing a fascinating statistical service called Stenstats, which show graphically a player or pitcher’s performance over a season, several years and in comparison with other players.”50 Stenhouse also served as a commentator on radio and television for the Expos, and on cable television for Pawtucket.51 He greatly enjoyed his broadcasting career: “It was really great — I did it for 12 years. Hardly anything I did I enjoyed more.”

Stenhouse has had an unusually intellectual post-baseball career. According to his LinkedIn profile as of 2015, where he deemed himself “Defender of the free-enterprise-system!”52 Stenhouse has since 2010 led two public-policy organizations in Rhode Island, the Ocean State Policy Research Institute and the Rhode Island Center for Freedom & Prosperity. He advocates for traditionally conservative economic approaches that would relax public-sector involvement with private businesses.

Stenhouse’s two sons, Garrett and Kevin, played baseball at Bentley University and the University of Rhode Island, respectively, before getting jobs in accounting and capital budgeting. Stenhouse has married twice, first to Sue, the mother of his two children, who has worked in Rhode Island city government, and to Wendy in 2003. On the staff of the library at Bryant University, Wendy first impressed Mike with virulent pro-Red Sox and anti-Yankee views that she expressed even after the September 11 attacks in New York when many New Englanders briefly stopped loathing their archrivals. Mike is stepfather to Wendy’s son, Neil.

While disappointed with his performance in the majors, Stenhouse still had a remarkable career overall considering his considerable collegiate and minor-league records. Nearly a generation after his playing days ended, Stenhouse expressed gratitude for the support of his family (“you cannot tell my story without their story”) and seemed contentedly engaged in his advocacy of free-market policies in his home state.

Notes

1 riheritagehalloffame.org/inductees_detail.cfm?iid=588 (accessed July 31, 2015).

2 Howard Sinker, “Stenhouse, Twins Turned Their Mutual Interest Into Reality,” Minneapolis Star and Tribune, March 14, 1985: D4.

3 Bob Monahan, “Stenhouse Picked in 1st Round by A’s,” Boston Globe, June 6, 1979: 67.

4 Robert Sidorsky, “A Couple of Classy Guys,” Harvard Crimson, April 22, 1978.

5 The 1986 Red Sox family would have at least one other Harvard connection. Rich Gedman’s daughter Marissa captained the Harvard women’s hockey team in 2013-2014 and played a prominent role on the Crimson’s national runner-up squad in 2014-2015. See uscho.com/stats/player/wid,8117/marissa-gedman/ (accessed June 30, 2015). After Rich’s father died in 1986, Stenhouse prepared to catch in case Boston needed an emergency backup. “‘I caught two innings in a simulated game in the Instructional League,’ said Stenhouse. ‘And I caught some bullpen in Montreal. … Hey, my brother’s a catcher [Dave Stenhouse was in the Blue Jays’ minor-league system]. It’s in the genes.’” Dan Shaughnessy, “There’s Just One Catch,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1986: 29. Stenhouse never caught in professional baseball.

6 Michael K. Savit, “Batsmen Edge Northeastern; Stenhouse Gets Five Hits in 19-2 Thriller,” Harvard Crimson, April 20, 1977.

7 Bill Scheft, “Harvard Baseball ’78: This May Be ‘Next Year,’” Harvard Crimson, March 22, 1978.

8 See gocrimson.com/sports/bsb/Record_Book/Records.pdf (accessed June 30, 2015).

9 Lesley Visser, “Harvard Stumbles, UConn Steals, 73-72,” Boston Globe, January 15, 1978: 86.

10 John Donley, “Cagers Can Dartmouth, 71-69; Stenhouse Sticks Jumper at :02 to Win It,” Harvard Crimson, March 1, 1978.

11 Statistics from sports-reference.com/cbb/schools/harvard/1978.html (accessed August 1, 2015).

12 Peter Gammons, “Why Sox Can Afford to Stall Rice signing,” Boston Globe, August 6, 1978: 81.

13 Ray Fitzgerald, “Stenhouse Is Still Waiting,” Boston Globe, July 31, 1979: 29.

14 Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations attributed to Stenhouse come from a telephone interview conducted August 1, 2015.

15 Nancy F. Bauer, “Oakland A’s Draft Fielder Mike Stenhouse,” Harvard Crimson, June 7, 1979.

16 Peter Gammons, “NL East Takes Turn for Better,” Boston Globe, July 22, 1979: 39.

17 Jeffrey R. Toobin, “Mike Stenhouse Meets Charles O. Finley,” Harvard Crimson, November 6, 1979. Toobin later gained renown for his legal commentaries for the New Yorker and various TV stations.

18 The Cubs picked Tom Henke 24th in this draft. Fans of the late, lamented Montreal Expos like the author of this profile wonder how history might have changed had the Expos picked (and signed) Henke instead of Stenhouse in 1980. If only Montreal could have rushed him to the majors the next year to face Rick Monday in Game Five of the 1981 National League Championship Series!

19 Mark H. Doctoroff, “Expos Pick Stenhouse Fourth in Draft,” Harvard Crimson, January 9, 1980.

20 “Class A Leagues,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1980: 45.

21 “Stenhouse Out Six Weeks; Felske Set to Go,” Harvard Crimson, April 4, 1981.

22 Jaki Schllsinger, “Majoring In The Minors,” Harvard Crimson, April 17, 1982.

23 Brian Kappler, “Will Stenhouse Find Lineup Spot?” The Gazette (Montreal), July 29, 1983: D-2.

24 “Class AAA Notes,” The Sporting News, September 12, 1983: 27.

25 Peter Gammons, “The Rookies of ’84,” Boston Globe, January 15, 1984.

26 Chuck Otterson, “Expos’ Stenhouse Slugging It Out in Fight for Job,” Palm Beach Post, March 14, 1984.

27 Peter Gammons, “Jury Still Out on Yankee Doodlings,” Boston Globe, March 18, 1984.

28 Ian MacDonald, “Stenhouse Making Noise With His Bat,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1984: 26.

29 Peter Gammons, “Sox Cut Clemens; No Big Surprises in Houk’s Moves,” Boston Globe, March 27, 1984.

30 Peter Gammons, “Time for Birds to Molt?” Boston Globe, April 22, 1984.

31 “Class AAA Notes,” The Sporting News, May 28, 1984: 39.

32 Bill James, The Bill James Baseball Abstract 1985 (New York: Ballantine Books, 1985), 211.

33 Thomas Rogers, “Expos May Seek McCarver,” New York Times, October 6, 1984. “Tanner has been traded once before during his managing career. The Pirates obtained him from the Oakland A’s in November 1976 in exchange for Manny Sanguillen, the catcher.”

34 Peter Gammons, “The Winter Game: The Dominican Republic Has Made Baseball a Game for All Seasons,” Boston Globe, January 25, 1985.

35 Peter Gammons, “The Winter’s Green for Dodger Blues,” Boston Globe, January 13, 1985.

36 Patrick Reusse, “Metrodome May Suit Stenhouse,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1985: 29.

37 Patrick Reusse, “Stenhouse Expected to Add Punch,” The Sporting News, January 21, 1985: 40.

38 Jim Henneman, “Thundering Drive Hospitalizes Snell,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1985: 14.

39 Larry Whiteside, “Red Sox Drop Pair to Twins,” Boston Globe, September 1, 1985: 53.

40 Joel Rippel, “Twins Trade Stenhouse to Red Sox,” Minneapolis Star and Tribune, December 13, 1985: D3.

41 Peter Gammons, “Stenhouse Joins Red Sox Bench,” Boston Globe, December 13, 1985: 39.

42 Bill James, The Bill James Baseball Abstract 1986 (New York: Ballantine Books, 1985), 143.

43 Dan Shaughnessy, “Baylor Feels at Home After Homer,” Boston Globe, April 4, 1986: 65.

44 Ian Thomsen, “Sax Sent down; Stenhouse Up,” Boston Globe, May 17, 1986: 26.

45 Larry Whiteside, “Red Sox Pinch Blue Jays in 10th,” Boston Globe, June 11, 1986: 53.

46 Dan Shaughnessy, “Time to Reach for the Stars,” Boston Globe, July 6, 1986: 54. In the 2015 interview, Stenhouse said Gammons gave him the nickname. Actually, he walked seven times in 16 plate appearances.

47 Dan Shaughnessy, “Burden on Clemens to Stop Downslide,” Boston Globe, July 25, 1986: 45.

48 Sam Smith, “Now a Mud Hen, He Has to Know if Rocky Path Leads Nowhere,” Chicago Tribune, August 3, 1987: B3.

49 Tom Loomis, “Stenhouse Still Has Big-League Hopes,” The Blade (Toledo, Ohio), March 25, 1987: 25.

50 Nick Cafardo, “Hobson: No Room for Error,” Boston Globe, December 20, 1992: 92.

51 Jim Greenidge, “A New Station in Life,” Boston Globe, June 14, 1996: 100; Jim Greenidge, “Ch. 68 Taking Its Best Shots,” Boston Globe, March 28, 1997: D10.

52 See linkedin.com/pub/mike-stenhouse/8/b73/813 (accessed June 18, 2015).