Eddie Yost – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

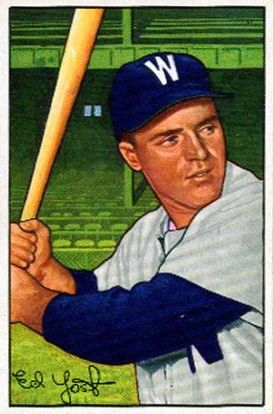

Eddie Yost was a slick-fielding, high-on-base-percentage third baseman, an athlete who continued to make his name at the hot corner after his playing days were over, as the third base coach for the Washington Senators, New York Mets, and Boston Red Sox. Known as “The Walking Man” for his propensity at getting bases on balls, he played in more games than any third baseman before him, though he was often overlooked because he spent most of his career in cavernous Griffith Stadium playing for the dreadful Senators.

Eddie Yost was a slick-fielding, high-on-base-percentage third baseman, an athlete who continued to make his name at the hot corner after his playing days were over, as the third base coach for the Washington Senators, New York Mets, and Boston Red Sox. Known as “The Walking Man” for his propensity at getting bases on balls, he played in more games than any third baseman before him, though he was often overlooked because he spent most of his career in cavernous Griffith Stadium playing for the dreadful Senators.

Edward Frederick Joseph Yost was born in Brooklyn, New York, on October 13, 1926. Yost attended John Adams High School in Queens, where he played baseball and basketball. Because of World War II, the rules allowed the freshman Yost to play both sports at New York University—shortstop in baseball, guard for the accomplished basketball team. “We used to fill Madison Square Garden every time,” Yost reminisced of the NYU basketball team. “I remember how most of us—Sid Tannenbaum, John Derderian, Frank Mangiapane, Ralph Branca—used to study down at Washington Square, then take the long subway ride up to University Heights just to practice every afternoon. We spent half our lives on the subway.”1 Mangiapane and Tannenbaum wound up playing basketball for the New York Knicks while Branca pitched for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Sam Mele, who preceded Yost on the NYU court and diamond, later played with Yost in Washington.

After his freshman year, Yost, still 17, had a weeklong trial with the Red Sox, staying at a hotel and working out at Fenway Park for the Boston brass. Though manager Joe Cronin reportedly liked what he saw, general manager Eddie Collins did not sign the young infielder. Washington scout Joe Cambria offered Yost a contract for $500—the Phillies offered double that amount but were a day too late. Signing with the Senators, Yost immediately reported to the major-league club, making his debut on August 16, 1944. He played in only seven games and batted .143, drawing one walk, the first of his 1,614 bases on balls. After the season, Yost turned 18, and joined the U.S. Navy.

He was placed on the National Defense Service List on January 23, 1945. In a letter to Senators owner Clark Griffith to inform the club of his draft status, Yost wrote, “I didn’t expect to leave quite so soon but as you said, they seem to be taking every available man. Thank you for the fine opportunity you gave me in the baseball world.…I hope I can fulfill that contract before long.”2

During his 18 months in the service, Yost spent the summer months playing baseball at the Naval Training Station in Sampson, New York, on Seneca Lake. That was the closest Yost ever got to the minor leagues. He was still 19 when he was discharged in 1946 and he finished out the year in Washington. The Senators wanted to send him to their farm club in Chattanooga so he could develop his skills and Yost even petitioned the commissioner’s office, willing to accept a waiver of the mandate in the GI Bill of Rights that guaranteed returning veterans their jobs—for baseball players their roster position—for two years. Commissioner Happy Chandler refused the request, not willing to set a precedent. Most veterans had the opposite problem that Yost had. Cecil Travis, a star shortstop for the Senators before the war, endured severe frostbite in the Battle of the Bulge and was never the same player. Travis was moved to third base so he wouldn’t have to range as far. By 1947, though, the youngster took over regular duty at third and Travis spent time at shortstop and on the bench.

“I didn’t think I was ready for the majors, but Chandler wouldn’t let me do it,” Yost said. “Then, a month after the season started I got into the lineup and played 115 games.”3 He wound up hitting .238 and remained Washington’s third baseman for a dozen seasons.

The 5-foot-10 right-handed hitter had a lifetime batting average of only .254, but because of his penchant for drawing walks, his career on-base percentage was .394. Yost’s best season with the Senators was 1950, when he hit .295 with 141 walks, and an on-base percentage of .440. One season, which best demonstrated the split between his batting average and his on-base percentage was 1956, when Yost hit only.231 but walked a career-high 151 times. His on-base percentage was a robust .412. Standing close to the plate, he was also hit by pitches 99 times in his career.

During that 1956 season, with Mickey Mantle receiving plenty of publicity for challenging Babe Ruth’s home run record of 60—the Mick wound up with 52 en route to the Triple Crown—the Senators issued a release about Yost’s challenge to the Babe’s 1923 record for walks. In late August, Yost averaged 1.1 walks per game and was on pace to break Ruth’s mark of 170. Though he fell short of the mark, Yost broke his own club record for walks and led the league by 39 over Mantle.

Had Yost played several decades later, in the free-agency era, his skills would have been much more valued. As it was, he made the All-Star team only once while playing on a Washington team that never finished better than .500 and ended up in last place five times during his career there. Moreover, Washington’s ballpark was cavernous—Griffith Stadium was 405 feet down the line in left field until it was reduced to 350 in 1957. Of the 101 home runs he hit as a Senator, 78 were hit on the road. He homered in every park in 1953—a year that he hit nine all told—and only one of those was hit at home. In his first seven full seasons as a Senator, only three of his 55 home runs were hit at Griffith Stadium.

Yost’s power was most prolific at the start of a game. His 28 career home runs leading off a game stood as the record until Bobby Bonds broke it in the 1970s. That mark was later shattered by Rickey Henderson, who also passed Yost, Ruth, and everyone else for most career walks. “Henderson’s the best leadoff hitter to ever play the game,” Yost said.4

Free agency might also have allowed Yost to wind up in a better situation than Washington, where the standing joke went, oft-repeated by Yost: “First in war, first in peace, and last in the American League.”

Yost may have languished playing for a perennial loser, but he was indeed appreciated.

Washington owner Clark Griffith, who sent his own son-in-law, Joe Cronin, to the Red Sox in a 225,000dealin1934,turneddowna225,000 deal in 1934, turned down a 225,000dealin1934,turneddowna200,000 offer from Boston two decades later for Yost. Griffith called him “the most sought-after .233 hitter in the American League” in 1953. “They look at his batting average and think they can swing a deal for him. I wouldn’t swap him for Mickey Mantle straight up, and to prove it, I’m paying him almost twice as much as the Yankees are paying Mantle.”5 Yost asked for, and received, a 5,000raisethatbroughthissalaryto5,000 raise that brought his salary to 5,000raisethatbroughthissalaryto21,000.

Griffith got his money’s worth out of Yost, who played 838 consecutive games from July 6, 1949, until tonsillitis finally knocked him out of the lineup on May 12, 1955. It was the longest such streak since the mark set by Lou Gehrig; like Yost, Gehrig was of German descent and the Iron Horse was his favorite player growing up. Yost had the fourth longest consecutive game streak in history at the time, and it still ranks ninth all-time.

Yost was certainly reliable and durable, but what about that batting eye? Yost retired with more walks than all but Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, and Mel Ott. Even today, with the walk more highly prized than it was in his day—and with more games on the schedule—Yost still ranks high among the all-time leaders in walks (1,614) and in walks percentage (17.59 percent of his plate appearances). Hall of Fame manager Bucky Harris, Washington’s skipper during Yost’s walking prime, once said, “What I’d like to have is a pair of Yosts: one to lead off and another to drive in some of those runs with the hits he makes.”6

As manager of the Yankees, Casey Stengel coveted Yost for his New York dynasty, but with no success. Stengel picked Yost for his only All-Star berth when the third baseman was batting .196 in 1952. Stengel defended his choice simply, “Every time I look up, that feller is on base.”7 Umpire Bill McGowan said of Yost, “The kid looks ’em over better than anyone else.”8

“It’s something you can’t teach. Just something I was lucky enough to be born with,” Yost told Sports Collector’s Digest four decades after his last game as a player. “First, I had a good eye at the plate and knew the strike zone. Also, I took the time to know the pitchers and how they worked. And I had enough bat control to be able to foul off a lot of pitches.”9 Illustrating that point, Yost fouled off 13 consecutive pitches in one at-bat in 1953; he fouled off seven his next time up.

“I also hit from a slight crouch and during my swing I was able to make my strike zone even smaller by dropping my right shoulder, “Yost explained. “Back then a lot of pitchers threw rising fastballs and I found that if I could lay off them and didn’t swing, they’d be called balls. And after a while I got a reputation for walking a lot and it seemed like the umpires began to give me the calls on the close ones.”10

Yost also kept an eye out for his fellow players. At a time when owners held all the cards in negotiations with players and took a dim view of anyone looking to change that, Yost served as the American League player representative. Yost, Robin Roberts, and Jerry Coleman even testified before the House antitrust subcommittee regarding the legal status of sports in June 1957. Though he attended college full-time for only one year before signing with the Senators, he did complete his education at NYU. Yost spent eight offseasons during his playing career accruing credits, eventually earning a master’s degree in physical education in 1955. He taught school in New York City, but his main occupation was baseball.

Yost was a bachelor for most of his playing career, sharing his home with his mother in South Ozone Park, Queens. He was ever popular in Washington. His fan club in Chevy Chase, Maryland, even put out a publication about the eligible bachelor’s doings. During the 1953 season, when teammate Bob Porterfield was zooming to 22 wins and perennial All-Star Mickey Vernon was winning a batting title, the fans held a night in support of Yost, hitting just .246 at the time. Among the gifts he was showered with was a new car.

Popular though he was, time keeps moving and younger players take the place of their elders. Yost was traded to the Detroit Tigers in December 1958 to make room for up-and-coming third baseman Harmon Killebrew. Calvin Griffith, president of the Senators since the death of his adoptive father Clark Griffith in 1955, traded the third baseman his adopted father wouldn’t have swapped for Mickey Mantle to the Tigers along with for two utility infielders, Reno Bertoia and Ron Samford, plus spare outfielder Jim Delsing (the Senators also sent infielder Rocky Bridges and outfielder Neil Chrisley to Detroit in the deal).

The short porch in Detroit was immediately to Yost’s liking. Eddie, who had dropped 10 pounds in the offseason, clubbed a career-best 21 home runs in 1959 and led the league in runs with 115. And after two years without drawing 100 walks—the first time since 1950 he had back-to-back years without reaching triple figures—Yost drew 135 bases on balls, his fifth time leading the American League. And that wasn’t an easy title to take with Ted Williams still in Boston. Yost led the league in walks for the sixth and final time in 1960. He also led the league in on-base percentage in both his seasons as a Tiger and was on base more than anyone else in the AL both years as well. As he was in Washington, Yost also served as team captain of the Tigers. Many things appealed to him in his new home. He even met his future wife, the former Patricia Healy, through the team. She worked in public relations for the Tigers.

After the 1960 season, the American League expanded by two teams and Detroit did not protect the 34-year-old Yost in the expansion draft. He was taken by the Los Angeles Angels. Yost became the first batter in Angels history when he popped up as the Angels’ leadoff man in the first inning in Baltimore on April 11, 1961. His second time up…he walked. It was not a great season for Yost, however, as he batted only .202, his lowest average as an everyday player. His on-base percentage was still .358, the 14th straight year it was .349 or better. He hit his 139th—and what turned out to be his last—home run in his last official at-bat in 1961—against the Senators, no less. His last time up that season…he walked.

In that final season, Yost was a part-time player and batted .240 with a .412 on-base percentage, the best of any Angel who played more than 10 games. Yost hoped he might play longer, but when George Thomas was discharged from the military, the Angels released the 35-year-old Yost to make room for Thomas.

While most people thought of Yost simply as The Walking Man, he was pretty good with the glove at third base. He set American League career records with 2,356 putouts, 3,659 assists, and 6,285 chances. He led the AL in fielding percentage twice, in assists three times, in double plays seven times, and in putouts eight times. Though Brooks Robinson later erased his fielding marks, Yost was the first third baseman in history to appear in more than 2,000 games.

Yost did not stay out of baseball long. The Senators he’d spent so many years with relocated to Minnesota and were rechristened the Twins, yet Yost was hired as a coach for the expansion Senators in 1963 as part of old friend and teammate Mickey Vernon’s staff. Yost was to be the first base coach, but he was moved to third base two days into the season. When Vernon was fired early in the season and Gil Hodges came over in a trade from the Mets to be Washington’s manager, some of the coaches were fired but Yost stayed on and forged a long friendship with Hodges.

By then married with two daughters and a son, Yost still lived in South Ozone Park when Hodges was dealt to the Mets after the 1967 season. The coaches were not part of the trade, but Hodges brought Rube Walker and Joe Pignatano from Washington along with Yost, who now worked five miles from his home. He was a fixture in the third base coach’s box in New York, trying to squeeze as many runs out of the paltry offense as possible through the judicious waving home of runners. Though Yost never came close to the World Series as a player, he earned a World Series ring with the Miracle Mets in 1969 and nearly got another in 1973.

Yost, Walker, and Pignatano were on hand when Hodges died of a heart attack after a round of golf in West Palm Beach just before the start of the 1972 season. Yogi Berra, also a coach under Hodges, was named manager. Yost remained with the Mets through 1976, when manager Joe Frazier changed coaches. The Red Sox hired Yost to take over the third base box for manager Don Zimmer. Yost remained there through the end of the Ralph Houk regime in 1984. In the wake of the 1969 victory, there were rumors of his becoming a manager—especially in Minnesota, still owned by Calvin Griffith—but it never happened. Yost spent 22 seasons waving runners home from third base and 39 consecutive years drawing a paycheck while in a major league uniform.

After years of living near his New York birthplace, the Yost family moved to Wellesley, Massachusetts. Among his newfound hobbies after retirement was working on antique clocks, which started from a class he took while coaching the Mets. He also restored antique carousel horses. Yost’s name inadvertently came up in political circles when it was revealed that 2004 Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry had said on a Boston radio program that “my favorite Red Sox player of all time is The Walking Man, Eddie Yost.”11 Yost, you’ll note, never played for the Red Sox, though he did serve as coach for eight seasons. A minor gaffe in some cities maybe, but in Sox-centric Boston, even Eddie Yost himself wouldn’t be able to put up the stop sign fast enough.

Yost died at age 86 in Weston, Massachusetts. Bruce Weber’s New York Times obituary aptly summed up Yost’s playing style: “He was the sort of pesky player who gave more powerful teams fits.”12

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “The Miracle Has Landed: The Amazin’ Story of how the 1969 Mets Shocked The World” (Maple Street Press, 2009), edited by Matthew Silverman and Ken Samelson.

Sources

Bedingfield, Gary, “Baseball During Wartime,” Eddie Yost. http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/yost_eddie.htm.

Bailey, Arnold, “Player Profile: The Walking Man.” Sports Collector’s Digest, January 18, 2002.

Kaus, Mickey, “Is Kerry Toast? No, He’s Yost!” http://www.slate.com/id/2104072/

McConnell, Bob, and David Vincent, eds., The Home Run Encyclopedia: The Who, What, and Where of Every Home Run Hit Since 1876. New York: Macmillan, 1996.

McGovern, Hugh, “The Walking Man,” 1977 Boston Red Sox yearbook (second edition).

Povich, Shirley, “Yost Too Good to Bat Leadoff.” The Sporting News, January 18, 1952.

Povich, Shirley, “Young Ironman Yost Keeps Strolling Along.” The Sporting News, October 6, 1954.

Rosenthal, Harold, “Yost Ready for First Move in 15 Years.” The Sporting News, January 15, 1959.

Washington Baseball Club Release, “Eddie Yost’s Threat to Babe Ruth’s Record Increases.” August 24, 1956.

Correspondence from Player File at National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

Notes

1 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Eddie Yost’s Hall of Fame player file.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Bruce Weber, “Eddie Yost, Baseball’s Walking Man, Dies at 86,” New York Times, October 17, 2012.

8 Unidentified newspaper clipping in Eddie Yost’s Hall of Fame player file.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Weber, New York Times, 2012.