Joe Hoerner – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Joe Hoerner lived to play baseball and nearly died to play the game. He endured nine years in the minor leagues, which included heart-related blackouts on the mound, before becoming one of the game’s early relief specialists.

Joe Hoerner lived to play baseball and nearly died to play the game. He endured nine years in the minor leagues, which included heart-related blackouts on the mound, before becoming one of the game’s early relief specialists.

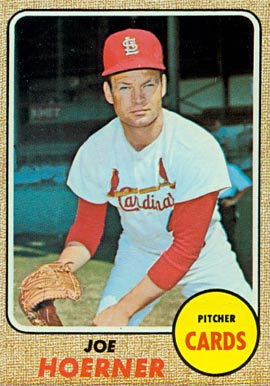

The left-handed sidearmer’s best seasons came with St. Louis (1966-69), during which the Cardinals won two National League pennants and the 1967 World Series. He was named a National League All-Star in 1970, after being traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. He possessed a competitive fire and a sense of humor that ranked him as one of the game’s leading pranksters. He also had a friendly and compassionate demeanor, frequently paying hospital visits to children and Vietnam War veterans. In a career that touched 14 major league seasons, Hoerner (6-foot-1, 200 pounds) appeared in 493 regular-season games — none as a starter.

Just as he lived the nomadic life while battling to secure regular duty in the majors, Hoerner did the same to hold it. He pitched for six teams his last six seasons. His first career hit was a home run, and his final pitch sparked a fistfight — and his ejection.

Joseph Walter Hoerner was born November 12, 1936, in Dubuque, Iowa, and grew up in adjacent Key West, a farming community. His father, Walter, was a farmer who became a deputy sheriff, and his mother, Gladys Marie (Woodrich), was a homemaker.

Sport was in the Hoerner bloodline. Joe’s older brother, Bob, played in the Chicago Cubs farm system and younger brother Jim received a tryout with the Chicago White Sox but decided against a baseball career. Two cousins were football stars: Dick Hoerner was an All-Pro running back in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and Mike Reilly appeared in the 1970 Super Bowl with the Minnesota Vikings.

His childhood baseball venues limited to sandlots and pastures, Joe Hoerner joined the Dubuque Senior High team as an outfielder, but coach James Nora soon had him taking regular turns on the mound. During his final high-school season, the summer campaign of 1954, Hoerner won a state tournament quarterfinal in relief and the semifinal on a one-hitter. His catcher was his younger brother Jim. (The future major leaguer was part of a formidable pitching duo. The other star was Jack Nora, the coach’s son, who struck out 14 and threw a one-hitter to win the state championship. A couple of months earlier, Dubuque Senior’s bid for the state title of the spring season was ended in an early-round game — even though Nora threw a no-hitter. After four years at the University of Iowa, Nora rose to Class AA ranks in the Kansas City Athletics organization.)

Hoerner nearly did not live to enjoy that championship season. After attending a rodeo, he dropped off his date, Darlene Naumann, and drove toward home. He apparently fell asleep, smashed his car into a tree and suffered serious injuries. When the emergency call reached authorities, his father Walter was on duty with the Dubuque County Sheriff’s Department. Joe Hoerner suffered a separated shoulder and broken ribs. Subsequent events suggested that other injuries escaped detection.

Hoerner decided not to attend college. Instead, he played semi-pro baseball and worked in the auto accessories department at the Sears Roebuck in Dubuque, where his older brother Bob managed the Appliance Department.

In 1956, Chicago White Sox officials, wanting a closer look at Hoerner, asked the Dyersville semi-pro team to start the lefty against their Waterloo affiliate, then managed by Ira Hutchinson. After watching him in that game and a follow-up workout, the White Sox offered Hoerner a minor league contract for 1957.

Hoerner did not disappoint in his first professional season. Assigned to Duluth-Superior, he went 16-5 and earned Northern League Rookie of the Year honors. He threw an 8-0 no-hitter against Aberdeen on May 12. (In an oddity, neither team recorded a strikeout.) Less than a month later, Duluth-Superior starter Al McKinney retired the first three Winnipeg batters but left the game with a sore arm. Hoerner came on in the second inning and held Winnipeg hitless the rest of the way. At the time, Hoerner said he did not realize he had handled eight-ninths of a combined no-hitter. The next month, he started in the Northern League All-Star Game, which pitted his league-leading team against the best players from the rest of the circuit.

After going together several years, Joe Hoerner and Darlene Naumann set their wedding for mid-February 1958. They figured that they would have several weeks together before he reported for minor league training camp. However, the White Sox had other plans. They pegged Hoerner as one of their Top Ten prospects and summoned him to major league spring training as a non-roster player. Camp began just one week after the wedding. Married only days, the groom shipped out for eight weeks in Florida. Spending the winter in Iowa — wives were discouraged from coming to spring training — Darlene Hoerner thus began her devoted role as a ballplayer’s wife.

The White Sox in 1958 assigned Hoerner to its Class B team in Davenport, Iowa (Three-I League). Pitching a home game one night, with his bride in the stands, he delivered a pitch and suddenly felt his heart racing. He gasped for breath and collapsed on the mound. An ambulance rushed him to a hospital. Hoerner remained unconscious for two to three hours, during which he received the Last Rites of the Catholic Church. “I think I was given up for gone,” he told an interviewer years later. In Dubuque, 75 miles away, his parents learned of the incident on that evening’s television newscast. Hoerner regained consciousness, the symptoms disappeared and, within days, he was back on the mound.

However, Hoerner continued to experience blackout “spells” — but only while pitching. The situation baffled his doctors, who conducted test after test but could find nothing wrong. Assigned to Class A Charleston (Sally League) for 1959, Hoerner spent virtually as much time in medical facilities as ballparks. He pitched only 28 innings all season. Eventually, physicians surmised that muscles near his heart were weak — perhaps a previously undetected injury from his auto accident as a teen. “It smashed everything else on my left side,” Hoerner said, “it just might as well have put a crimp in my heart.” Some doctors urged him to quit baseball — advice the 22-year-old, who during the off-season became a first-time father, was not inclined to follow. Other doctors speculated that Hoerner’s overhand pitching delivery was somehow constricting an artery. Some accounts credit doctors and others cite Ira Hutchinson, the former Waterloo manager who became Hoerner’s skipper in Davenport, but someone suggested that Hoerner alter his pitching motion and see if that made a difference. The lefty “dropped down” and became a sidearmer.

The White Sox stuck with Hoerner through the 1961 campaign, including two winters in the Florida Instructional League. However, in November 1961, the expansion Houston Colt .45s selected him in the minor league draft. Thus began four frustrating years during which he felt he never received a fair shot at the major leagues.

With the Houston organization, Hoerner bounced around in minor-league assignments, including Class A Savannah (on loan to the White Sox affiliate), Class AA San Antonio and Class AAA Oklahoma City. He pitched well for three seasons in the Puerto Rico winter league (1963-65), playing on the league champions in 1963 and setting a league record for ERA (1.21) in 1964. However, during the regular season, Houston used him just a total of 14 major-league innings in 1963 and 1964 and not at all in 1965.

Hoerner’s major league debut came September 27, 1963, when the Colt .45s staged a late-season publicity stunt — fielding an all-rookie lineup against another expansion club, the New York Mets. (Houston’s starting pitcher was 17-year-old Jay Dahl, who gave up seven runs in 2 2/3 innings. It was the only major league appearance for Dahl, who died in an auto accident less than two years later.) Hoerner retired his first batter, rookie Ron Hunt, on a pop-up and gave up no runs on two hits over three innings. The debut game was his only big-league appearance of 1963.

In 1964, he opened the season with the Colt .45s. Still unproven at the major-league level, Hoerner earned some ink for demonstrating his mischievous side against Dodgers veteran Don Drysdale. Los Angeles was coasting to a win when Drysdale came to bat in the seventh inning. The Sporting News reported it this way: “Hoerner threw him [Drysdale] a pitch that dipped and darted very suddenly just as it came up to home plate. Drysdale, who doubtless had thrown a few himself, recognized it as a spitball and started laughing. He looked out at the mound and caught Hoerner’s eye and Hoerner started laughing. Drysdale stepped out of the box and looked around at umpire Vinnie Smith, and the ump was laughing, too. ‘I’d say,’ Smith chuckled to Drysdale, ‘that he threw you a pretty good one.’” Not everyone was laughing afterward, however. In the following week’s edition, a Sporting News editorial critically cited the Hoerner-Drysdale-Smith incident (among others), saying that if baseball won’t enforce the ban on the spitball, it might as well legalize the pitch. Unrelated to that tempest, the Colt .45s sent Hoerner back to the minors after seven relief appearances, 11 innings, no decisions and a 4.91 earned-run average.

The relocations and uncertainty were tough enough for the ballplayer — but perhaps tougher on his young family. Darlene gave birth to the couple’s third child — their only son, Ronald — just days before Christmas in the unfamiliar surroundings of a San Juan hospital. In just two years, their daughter Sharon attended 11 schools (some of them return visits). By Darlene’s calculation, the Hoerner family had 35 residences before Joe became a major league regular. Some of the reassignments were particularly wrenching. In 1961, after spending just a month at AAA San Diego, the White Sox sent Hoerner to Single-A Charleston, necessitating an immediate cross-country drive — without air conditioning and with a 2-year-old daughter in tow.

Darlene recalled one move, just before opening day in AAA Oklahoma City. The day they moved the Hoerners’ belongings from the rental trailer into an apartment, Darlene and her parents returned from the grocery store when Joe came in from practice to reveal that he had been demoted to AA San Antonio. Darlene and Joe gave away the groceries, repacked the trailer and drove overnight, through a raging thunderstorm, to Texas. With them were their two daughters, 3-month-old Jolene and 4-year-old Sharon. “I never complained. I accepted it,” Darlene said. “It was part of the game and part of his life. Joe had a dream and it was to play in the major leagues. I would do nothing to jeopardize this dream.”

For a while, it appeared that the dream would not be realized. Hoerner blamed Houston General Manager Paul Richards. “Joe felt that Paul Richards didn’t have faith in him,” his wife said. “Richards didn’t think he could get right-handers out in the major leagues,” though he was succeeding against righties in the minors. “He (Richards) felt he needed another pitch.” The southpaw contemplated retirement. Darlene noted that their family received no relocation reimbursement when reassigned. He had no pension, and the team provided health insurance only for the player — and then only during the season. “Darlene would call and say Joey was thinking of giving it up,” his brother Jim recalled. “My brother Bob would get right on the phone and talk to him and tell him he needed to stick with it.”

Meanwhile, Hoerner’s manager in Oklahoma City, Grady Hatton, felt that Hoerner’s best bet for making the big leagues was as a reliever, and he started using him in that role. In 1965, though he pitched outstanding ball (8-3, 1.94 ERA) for Pacific Coast League champion Oklahoma City, Hoerner did not receive a September call-up to Houston.

Discouraged, Hoerner nonetheless agreed to play one more winter in Puerto Rico. There, Roberto Clemente was a teammate. “Roberto asked Joe why he wasn’t in the majors,” Darlene recalled. A St. Louis Cardinals scout asked Hoerner the same question. “Joe just told him about Paul Richards,” his wife said. “Joe told the scout he just knew he could be effective in the majors.” The Cardinals apparently agreed, because in November 1965 they grabbed Hoerner in the Rule 5 draft. Hoerner’s fortunes were about to take a significant turn for the better.

Hoerner, who relied on a fastball and slider, did not impress Manager Red Schoendienst in spring training 1966. “We gave him a good shot, but he didn’t pitch well,” Schoendienst recalled. “His control was off quite a bit.” However, coaches and scouts assured the manager that Hoerner was a notorious slow starter. “They told me, ‘Just hang with him. He’ll come around.’” The manager never questioned the lefty’s desire. “He was competitive. I saw that the first time he was on the ball field.” Hoerner made the team, and Schoendienst’s patience was rewarded.

Hoerner recorded his first major league save May 19, 1966, at Philadelphia. His first victory came 10 days later, when he gave up one hit over three innings as the Cardinals prevailed over Cincinnati in 10 innings. The 29-year-old rookie kept it up, finishing with a 5-1 record, 13 saves and a team-best ERA of 1.54. Hoerner proved that he belonged in the big leagues.

Hoerner, who batted from the right side, was never an offensive threat. As a reliever, he had only 59 at-bats in his entire career, and struck out in more than half of them (32). However, he made the first of his six career hits memorable, launching a three-run homer entirely out of Chicago’s Wrigley Field on July 22, 1966. Back in Iowa, his cousin Mike Reilly heard the home-run call on his car radio. “I nearly drove off the road,” he laughed.

Though generally considered all business on the field, Hoerner was a prankster outside the lines. In an airport one day, he surprised his teammates waiting in the baggage claim area by sliding out the luggage chute. He hit only .102, but a couple of stunts involved a bat. His favorite trick was to startle a teammate by sneaking behind him and slamming a bat against a folding chair. He made history of sorts by doing what designers claimed was impossible — hitting the Astrodome roof with a batted ball. He did it several times. During pre-game warm-ups he would toss up a ball and slug it with a fungo bat. “Most of his pregame shots have hit the sloping area between home plate and the pitcher’s mound, about 175 feet up,” Sports Illustrated noted, “but some of them have attained the dome’s 208-foot zenith.” Before a game in Los Angeles, Hoerner and some teammates had a little competition to startle some patrons in a Dodgers Stadium skybox. The contest involved tossing a baseball against the supposedly “unbreakable” skybox window. Hoerner’s toss smashed a pane.

Perhaps Hoerner’s boldest prank occurred when he commandeered the Cardinals’ bus. After a game in Atlanta, players and other team personnel waited on their charter bus to ride to their hotel. The bus driver could not be located. “All of a sudden, Joe says, ‘I know how to drive a bus,’” Schoendienst recalled. The manager disembarked, ostensibly to look around for the driver. Nervous about the developments, broadcaster Harry Caray got off, too. “All of a sudden, the bus took off,” Schoendienst said. Teammate and future business partner Dal Maxvill said, “The problem was, Joe couldn’t shift gears very well, so there was a lot of shaking.” Hoerner managed to get the bus to the hotel, 10 minutes from the ballpark. However, he cut a turn too closely and damaged the hotel’s sign. “When you do things like that and you are a winning team, it is considered ‘colorful,’” Maxvill observed. “If you’re a losing team, you’re called a troublemaker and you’re traded.”

Fortunately for Hoerner, he was part of a fun-loving team — and a winning team. The Cardinals won the National League the last two seasons before the major leagues introduced the League Championship Series. In 1967, after going 4-4 with a 2.59 ERA and 15 saves, Hoerner made his first World Series appearance in Game 2, when he was summoned to face Boston’s Carl Yastrzemski with two men on base. Yaz launched a three-run homer. Hoerner also struggled in his other Series game (amassing a 40.50 ERA in his two appearances). However, the Cardinals defeated Boston in seven games, with Bob Gibson claiming his third victory of the series in the finale. Within minutes, Hoerner’s career nearly came to a freakish end. Celebrating the World Series title in the visitors’ clubhouse, Hoerner suffered a severed tendon in the middle finger of his pitching hand when the champagne bottle he was holding exploded. “I was very, very worried that my baseball career was over,” he told an interviewer.

Hoerner underwent treatment and physical therapy throughout the winter of 1967-68, all the while uncertain whether his hand would heal properly. Not only did he recover fully, Hoerner in 1968 posted career-bests for record (8-2), ERA (1.47) and saves (17). He tied the National League record for consecutive strikeouts in relief (six Mets in the ninth and 10th innings June 1). And he helped St. Louis return to the World Series.

In Game 3 of the Fall Classic, in Detroit, Hoerner pitched what he considered his most memorable game. With one out in the bottom of the sixth inning and the Cardinals leading 4-3, St. Louis starter Ray Washburn walked two straight batters. Schoendienst called for Hoerner. With his wife and parents in attendance, the southpaw proceeded to limit the Tigers to one hit and one walk the final 3 2/3 innings. It would be the only World Series save of his career. (And, for good measure, Hoerner stroked a rare single in the eighth inning.) Hoerner went from highlight to lowlight: In Game 5, he took the loss after he failed to retire any of the four Tigers he faced. Detroit dethroned the Cardinals when World Series MVP Mickey Lolich outpitched Bob Gibson in Game 7 in St. Louis.

After the 1968 World Series, the Cardinals spent five weeks in Japan on an 18-game exhibition tour. On the trip, Hoerner and Maxvill made the acquaintance of an American travel executive representing Japan Airlines. Shortly afterward, the ballplayers and two or three other investors established Cardinal Travel, Inc. Eventually, Hoerner and Maxvill bought out the other investors of the St. Louis-based travel agency.

About this time, Joe and Darlene Hoerner also decided, in consideration of their school-age children, to put down roots in St. Louis. In light of the nomadic lifestyle and tiny apartments they had endured the previous dozen years, it was a significant development. During the off-season, Hoerner represented the Cardinals, promoting the club in speeches around the Midwest.

In 1969, the first season under divisional play, the Cardinals dropped to fourth in the National League East. Hoerner remained steady; he posted a 2-3 record, ERA of 2.87 and 15 saves.

However, that October, the Cardinals and Philadelphia Phillies made a seven-player deal. St. Louis traded Hoerner, Tim McCarver, Byron Browne and Curt Flood for Jerry Johnson, Dick Allen and Cookie Rojas. Flood refused to join Philadelphia and sued baseball to attempt to gain his free agency. After commissioner Bowie Kuhn ruled against him, Flood retired rather than report to the Phillies. While the Flood case played out in court, the rest of the players involved in the deal — including a shocked and disappointed Joe Hoerner — reported to their new teams. (The Cardinals eventually sent Philadelphia two more players to compensate for Flood.)

In the nightcap of a late June 1970 doubleheader, Hoerner, facing his former teammates in St. Louis, suffered another heart spasm. He was carted off to a hospital. As was the case with his previous episodes, a cardiogram revealed no abnormalities, and he returned to the team the next day. A week later, New York Mets manager Gil Hodges selected Hoerner to the 1970 National League All-Star squad. Hoerner was one of the few players to NOT play in what turned out to be a memorable 12-inning marathon in Cincinnati. Hometown favorite Pete Rose scored the winning run from second on a two-out single by dislodging the ball from the grasp of catcher Ray Fosse in a violent collision. At that moment, according to his brother Jim, Hoerner was taking his final warm-up tosses in anticipation of the 13th inning. Thus ended Hoerner’s only All-Star experience. He completed his first season in Philadelphia (9-5 record, 2.65 ERA and nine saves) and returned to his home in St. Louis. During the off-season, he hunted, fished and presented programs before schoolchildren and community groups.

After going 4-5 with a 1.97 ERA and nine saves in 1971, Hoerner was pitching capably for the last-place Phillies through the initial third of the 1972 campaign. The Hoerners had come to like Philadelphia, though they preferred St. Louis. In mid-June 1972, however, the Phillies shocked Hoerner by trading him (with Andre Thornton) to Atlanta for pitchers Jim Nash and Gary Neibauer, both of whom were at the tail end of their careers.

When he joined the Braves, Hoerner was 35 years old and losing his effectiveness. In mid-1973, the Braves sold him to the Kansas City Royals, who kept him through 1974. “He persevered and dealt with the trades,” his wife said. “As long as he could stay in the major leagues, he wanted to remain in the game.” The Phillies brought him back for 1975, but used him just 21 innings, and cut him loose in the off-season. The Texas Rangers signed the 39-year-old reliever for 1976, when he recorded eight saves (to offset an 0-4 record and 5.14 ERA) in 35 innings. When the Rangers released him at season’s end, Joe Hoerner’s major league career appeared over.

However, Hoerner would not give up. He signed a minor league contract for 1977, agreeing to be a player-coach, and reported to Indianapolis. Nearly three months into the season, the Cincinnati Reds were desperate for pitching. They brought the 40-year-old reliever back to the majors.

In his first big-league appearance of the year, June 22 in Philadelphia, Hoerner was summoned with the bases loaded. He unleashed a run-scoring wild pitch, intentionally walked the bases loaded and then served a grand-slam offering to the light-hitting Larry Bowa. Five days later, Hoerner hit two consecutive batters and gave up another grand slam — this time to slugger Willie McCovey. (It was McCovey’s second homer of the inning.) It did not get any better after that. Hoerner appeared in only eight games in 1977, pitched only 5 2/3 innings and posted an ERA of 12.71.

His playing career came to a dubious conclusion. On August 5, 1977, with more than 50,000 fans packed into Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium for a twi-night doubleheader against Pittsburgh, Hoerner received a mop-up assignment in the opener — the ninth inning of a 12-1 Pirate romp. Hoerner retired his first two batters, then hit Frank Taveras with a pitch. The Pirate shortstop took exception, flung his bat at Hoerner and rushed the mound. When Taveras arrived, Hoerner greeted him with a punch to the face. Umpires ejected Taveras and Hoerner. Taveras returned for the nightcap — and hit an inside-the-park grand slam. Hoerner never returned; the pitch that struck Taveras was the last of his career.

Looking back on his departure from the big leagues, Hoerner said, “It was fairly easy to accept, really, and after traveling all those years — in planes, cars and even … buses — I really didn’t miss that part of the game… It was time to walk away.” Retirement from baseball also allowed him more time for his family, charity events, Kiwanis Club and outdoor interests — hunting, fishing, camping and golfing. Hoerner was instrumental in lining up players for benefit golf tournaments and “Field of Dreams” celebrity baseball exhibitions on the Iowa field where the 1980s movie was filmed.

Hoerner turned his professional attention to Cardinal Travel, of which he was vice president. His ex-teammate Maxvill was president. He often accompanied tour groups to various locations — including St. Louis spring training camps, the “Cardinal Cruise” and the National League cities the Cardinals visited. In that role, and his support of the St. Louis Pinch Hitters, a not-for-profit women’s charitable organization in which his wife was active, Hoerner remained close to the Cardinals organization.

Hoerner was involved in a fatal boating accident the last night of June 1984 while returning from a family outing on the Lake of the Ozarks, a popular resort area in Missouri. About 10:30 p.m., the boat that Hoerner was operating collided with a small runabout that, according to Darlene, was motionless on the lake and without lights on a dark night. Two 25-year-old men on the runabout were killed, and three other men were injured. There were injuries aboard the Hoerner vessel as well. A family friend was hospitalized and Darlene, momentarily knocked unconscious, suffered head and back injuries. Another fatality was narrowly averted even though the collision propelled the retired ballplayer into the lake. Hoerner, who could not swim, nearly drowned. In that frantic and dark setting, his son Ron, son-in-law Wayne McDaniel and daughters Sharon and Jolene took part in his rescue. Soon afterward, authorities cited Hoerner on misdemeanor charges of reckless and negligent operation of a motorboat. He fought the charges. “They wanted Joe to plead guilty,” Darlene said, “but he wouldn’t plead guilty to something he didn’t do.” Recalling the incident more than two decades later, Darlene said that authorities tampered with evidence and pushed the case to generate publicity about boating safety by using a local sports celebrity’s name. After three hours of deliberation, a jury acquitted Hoerner. “The trial proved that the evidence was falsified,” Darlene said. Though cleared of all charges, the accident and legal process left her husband shaken.

Eventually, Hoerner returned to his leisure pursuits and charitable endeavors. Among the beneficiaries was Maryville University in St. Louis, where for 19 years Hoerner volunteered as a fund-raiser and athletics adviser. Though he never attended college, Hoerner often spoke to young people about the value of an education. Maryville later established a scholarship in his name.

Tragedy struck again — and finally — on October 4, 1996, when Hoerner died in a farm accident in Hermann, Missouri. Working alone while tilling a friend’s field, the 59-year-old somehow was pinned between the tractor fender and a tree trunk. (Most media accounts erroneously reported that he was run over by the tractor, his widow noted.)

His funeral was held in Christ Prince of Peace Catholic Church in suburban St. Louis, where another retired relief specialist, Al Hrabosky, then a Cardinals broadcaster, delivered a eulogy. Hoerner was laid to rest in Resurrection Cemetery, St. Louis. At the time, his survivors included his wife, Darlene; daughters Sharon (Wayne) McDaniel and Jolene (Ray) Vollmer; son Ronald; grandchildren Heather, Lindsey and Jeremy McDaniel; his father, Walter; and brothers Robert, John and James; and sister Ann Lambe.

In the days and weeks after Joe Hoerner’s death, tributes flowed to St. Louis. Many mentioned his achievements as a player, and even his pranks, but many more emphasized his accomplishments and contributions off the field — as a man who showed heart.

Sources

Chicago Tribune

Craft, David and Owens, Tom. Redbirds Revisited. Chicago: Bonus Books, 1990

Los Angeles Times

Telegraph Herald, Dubuque, Iowa

Hoerner, Darlene

Hoerner, James

Hoerner, Robert

Maryville University, St. Louis

Maxvill, Dal

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Schoendienst, Albert “Red”

The Sporting News