Deacon McGuire – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

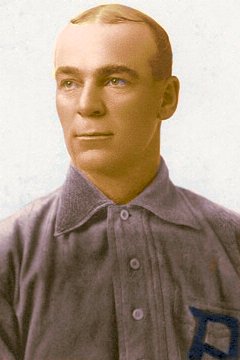

James Thomas McGuire, who would be known as “Deacon Jim” based on his gentlemanly, fair-play approach to the game, was the most durable catcher of his era. It was widely reported that he was never put out of a game or fined. He was steady in performance and temperament with some of his greatest baseball years taking place for terrible teams. He was not flamboyant but hardworking, and though he was appreciated as a baseball great in his home of Albion, Michigan, his place in baseball history is all too often overlooked. He endured aches, pains, and injury — including breaking every finger of both hands — to create a legacy of resilience and fortitude that encompassed a then-unheard-of 26 big-league seasons at arguably the sport’s most demanding position.

James Thomas McGuire, who would be known as “Deacon Jim” based on his gentlemanly, fair-play approach to the game, was the most durable catcher of his era. It was widely reported that he was never put out of a game or fined. He was steady in performance and temperament with some of his greatest baseball years taking place for terrible teams. He was not flamboyant but hardworking, and though he was appreciated as a baseball great in his home of Albion, Michigan, his place in baseball history is all too often overlooked. He endured aches, pains, and injury — including breaking every finger of both hands — to create a legacy of resilience and fortitude that encompassed a then-unheard-of 26 big-league seasons at arguably the sport’s most demanding position.

McGuire’s major-league journey began in 1884 with the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association, where he split time behind the plate with Fleet Walker, the first African American regular player in major-league history. He did not play his final major-league game until 28 years later in 1912 filling in during the famed “strike game” when the Detroit Tigers (for whom he was a coach) walked out in support of an indefinitely suspended Ty Cobb. In between, McGuire played in a record number of seasons for a record number of teams and set career catching marks for defensive games, putouts, assists, caught stealing, and stolen bases against. The last three of these marks still stand.

Born in Youngstown, Ohio, on November 18, 1863, during the Civil War, McGuire grew up in Cleveland and later moved to Albion, Michigan. Though his baseball career was nomadic, Albion remained an anchor and McGuire would an integral part of the city’s fabric during his life. He grew up with a love of baseball and hard work. While still young, McGuire worked during the week as an apprentice iron molder, which strengthened his already powerful frame.1 His large hands made him well-suited to play catcher in these pre-mitt days. McGuire’s work kept him from playing baseball during the week but he was able to play on weekends. He evolved into a “rawboned young catcher with powerful hands and frame that was tougher than pine knots.”2 McGuire first gained some measure of baseball fame when he was touted as the only backstop who could handle the throws of Charles “Lady” Baldwin, the up-and-coming pitching star from Hastings, Michigan, 50 miles from Albion, who was known for his “snake ball.” In the context of the times, the ability to catch difficult or different pitches was key to evaluating the abilities of a catcher.3 This pairing of Baldwin and McGuire proved fortuitous, as both of these young men went on to significant major-league success.

McGuire began his professional career for the Terre Haute Awkwards in 1883. The quality of the ball and facilities belied its independent team status as the best ballplayers from the area were recruited and the team had a new enclosed state-of-the-art stadium called the Amphitheater.4 Terre Haute merged with another top team, the Indianapolis Blues, during the season. Tryouts were conducted to trim down the squad, and McGuire made the cut along with future major leaguers Charles Krehmeyer, “Cod” Myers, and Ed Halbriter.5

In 1884 Terre Haute joined the Northwestern League but McGuire signed with the Cleveland Blues of the National League, only to be released shortly thereafter without making a regular-season appearance with the team. His big-league ambitions would be realized when he joined the Toledo Blue Stockings (1883 Northwestern League champions) which had joined the major-league American Association in 1884. McGuire shared catching duties with Fleet Walker. Sadly, this was Fleet Walker’s only big-league season due to racism, and a color barrier that was raised and maintained until Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers 63 years later. McGuire hit only .185 in 45 games for the eighth-place (46-58) club. It is alleged – and often attributed to wife May (Huxford) McGuire — that he would put beefsteak into his fingerless glove to help protect his already-gnarled hands from the incredible velocity of pitcher Hank O’Day’s shoots.6

The Blue Stockings returned to the minors the following year and McGuire signed with the minor-league Indianapolis Hoosiers of the Western League. McGuire had played 16 games (.246) for the team when the Detroit Wolverines of the National League purchased him and eight teammates. McGuire was reunited with Lady Baldwin in Detroit and caught 31 games, splitting time with primary catcher Charlie Bennett (62 games). McGuire hit .190 in 34 games for the sixth-place (of eight) Wolverines.

In 1886, McGuire joined his third team in three major-league seasons. He played for the Philadelphia Quakers, sharing catching time with Jack Clements. Once again, McGuire proved a solid backstop who was weak at the plate, batting .198. He showed enough to be brought back in 1887 and both he and the team improved. The ’87 team finished in second place with a 75-48 mark behind McGuire’s former team, the Detroit Wolverines. McGuire batted .307 (measuring his average by current standards; in 1887 bases on balls counted as hits). This personal success was short-lived as 1888 saw him bounce from Philadelphia (12 games, .333) back to Detroit (three games, .000) and finally to Cleveland of the American Association (26 games, .255). He was back in the minors in 1889 playing for the Toronto Canucks of the International League. McGuire batted a solid .282 in 93 games for the Canucks.

McGuire returned to the bigs in 1890 and batted .299 for Rochester of the American Association. His solid season was the beginning of his evolution from good-field, no-hit journeyman to a star at the position. Unfortunately, his greatest individual seasons would be for a team that languished in the league’s cellar. In 1891, he joined the Washington Statesmen of the American Association and led all starters in batting at .303. Additionally, he led the team in doubles, triples, home runs, and RBIs. In the field, McGuire led the league in assists and runners caught stealing, but also in errors by a catcher.

The Washington team, renamed the Senators, survived the consolidation of the National League and the American Association but McGuire’s productivity regressed in 1892. McGuire batted just .232 while driving in 43 runs and leading catchers in stolen bases allowed. The Senators had started the season strong but soon dropped back to tenth place in the 12-team league. The 1893 season saw McGuire splitting time at catcher with Duke Farrell, playing 50 games behind the plate to 81 by Farrell. The careers of these two stellar catchers became inextricably linked for years to come. McGuire hit .257 and Farrell .282 for the last-place club. Farrell was traded to the New York Giants in 1894, leaving McGuire to carry the catching load. He rebounded at the plate, hitting .306 with 78 RBIs for an 11th-place Senators team. His success in 1894 only vaguely foreshadowed his historic 1895 season.

In 1895, McGuire set the record for most games caught in a season (133) in the history of the major leagues to that point. As pointed out by David Nemec in his Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball, “Deacon McGuire of Washington became the first catcher in the post-1893 era to lead his team in hitting as well as the last catcher until 1944 to lead his team in at-bats.”7 In addition to leading the club in batting (.336) and at-bats, he tied for the team lead in RBIs (97) and was second in home runs with 10 (fifth in the league). Behind the plate, he led all catchers in putouts, assists, errors, passed balls, stolen bases allowed, and caught-stealings. His record of 189 players caught stealing still stands. Unfortunately, the team was still terrible with a record of 43-85 plus five ties, good only for tenth place in the twelve-team loop.

The 1896 season proved another solid one for McGuire. He again led the majors in games caught at 98 and led the NL in putouts, errors, and stolen bases allowed. His highly productive hitting continued as he batted .321 with 70 RBIs. He was once again splitting time with Duke Farrell (.300), who had been traded back to Washington to serve as McGuire’s backup. Despite his productivity, the Senators continued to be dismal, finishing in ninth place at 58-73. In 1897, the two catchers again shared duties with McGuire catching 73 games and Farrell 63. The veteran catchers were a highly productive tandem with McGuire batting .343 and Farrell .322. The team improved to 61-71 for a sixth-place finish, though never threatening to be successful.

In 1898, McGuire hit .268 (catching in 93 games) and Farrell hit .314 (catching 61 games). The team was simply dreadful, finishing with over 100 losses at 51-101. The season, however, did provide McGuire his first shot at managing the team — with usual Washington results (21-47). On the home front in 1898, Deacon Jim purchased an ice business with his brother to serve Albion.8 According to local Albion historian Frank Passic, “This was during the days when ice was cut in the winter from the Kalamazoo River and at Duck Lake and stored for use in ice boxes throughout the year.”9

In 1899, McGuire was back to being the primary catcher without the responsibility of managerial duties. Platoon mate Farrell had been traded to Brooklyn early in the season. McGuire was batting .277 for another awful Washington team (catching 56 games) before being traded to the Brooklyn Superbas (joining Farrell) where he immediately made an impact, hitting .318 in 46 contests. This was a fortunate trade for McGuire, as he was joining an immensely powerful and star-studded Brooklyn club. The roster had been a beneficiary of the final season of legal syndicate ownership. The ownership of the Baltimore and Brooklyn were in partnership and the Superbas team now included quite a number of former Orioles.

The team was led by future Hall of Fame manager Ned Hanlon, who had been with Baltimore the year before and had managed the Orioles to three pennants and two second-place finishes in the prior five years. The already solid pitching of Brooklyn heroes Jack Dunn (23 wins) and Brickyard Kennedy (22 wins) was bolstered by former Orioles Jim Hughes (league-leading 28 wins) and Doc McJames (19 wins). Brooklyn regulars Tom Daly (2B, .313) and Fielder Jones (OF, .285) were joined by Baltimore’s future Hall of Famers Wee Willie Keeler (OF, .379), Joe Kelly (OF, .325), and Hughie Jennings (1B, .296) as well as Bad Bill Dahlen (SS, .283). Starting catcher Duke Ferrell and starting third baseman Doc Casey had come from Washington in a trade involving two former Orioles. The team sailed to the championship with a 101-47 record, eight games in front of the Boston Beaneaters.

While syndicate ownership was gone in 1900, the league was reduced from 12 to eight teams and the already powerful championship Brooklyn team was aided in 1900 by the arrival of Iron Man Joe McGinnity (league-leading 28 wins) from the former Baltimore franchise along with pitchers Frank Kitson, Harry Howell, Jerry Nops, and 3B Lave Cross. The team again finished on top of the NL. Farrell (catching 74 games) and McGuire (69 games) split duties at the backstop and hit .275 and .286, respectively. After his many years behind the plate toiling for bad teams, McGuire had now been an important part of two championship teams. As for personal accomplishment, by 1900 no player had caught more games in the history of baseball. McGuire had surpassed the mark of Hall of Fame catcher-manager Wilbert Robinson.

Brooklyn dropped to third place in 1901 with McGuire hitting .296 (catching 81 games) with Farrell also at .296 (catching 59 games). The durability marks continued to fall to McGuire as he became the all-time catching leader in putouts, assists, and stolen bases allowed. While Farrell was back with Brooklyn in 1902, McGuire was traded to Detroit in the American League. McGuire was the oldest member of the club at 38 and he caught 70 games while sharing time with 26-year-old Fritz Buelow (.223). McGuire hit .227 for the lowly Tigers, who finished seventh place. Back with the Tigers in 1903, McGuire again served as the primary backstop, again splitting duties with Buelow. McGuire raised his average to .250. The team improved to 65-71, finishing in fifth place.

In 1904, the New York Highlanders were in need of a catcher and purchased McGuire and put him behind the plate as their primary backstop. At 40 years old, he was by now the oldest player in the league but played more games (101) and caught more games (97, third in majors) this season than he had in any of the new century. This was a remarkable feat of durability considering the leader in games at catcher that year was the 29-year-old Billy Sullivan of the White Sox at 107 followed by a 28-year-old Johnny Kling with 104. With player-manager Clark Griffith at the helm and led by the pitching of Jack Chesbro (41 wins), Jack Powell (23 wins), and the hitting of Wee Willie Keeler (.343), the Highlanders finished just a game and a half behind Boston for second place in the AL. While providing solid work behind the plate, experience, and leadership McGuire would bat just .208.

McGuire was back again in 1905, catching 71 games and hitting .219, but was now splitting time with 27-year-old Red Kleinow. The team finished at 71-78, in sixth place. In 1906, McGuire played 51 games. His batting average improved greatly in this smaller sample; he just missed batting .300, finishing at .299. The team returned to second place behind the White Sox at 90-61 seeing the emergence of first baseman Hal Chase (.323). Al Orth (27 wins) and Jack Chesbro (23 wins) led the pitchers.

Having been measured with money as with seemingly all aspects of his life, and perhaps sensing his baseball odyssey was coming to an end, he opened a saloon with his brother George (“McGuire Brothers”) at 204 S. Superior St. in Albion before moving (after seven years) to West Porter St.10Hanging over the bar was a “large life-size framed photograph of ‘Deacon Jim’ the baseball hero in his Detroit Tigers uniform.”11 The change in location of the enterprise included turning the establishment into a café-restaurant with prohibition coming to Albion.12 There were also reports that he purchased a mill four miles from Albion around this time.

Claimed off waivers in 1907 by Boston Red Sox, McGuire served mostly as manager, taking over a 14-29 team. McGuire did not fare much better at the helm, going 45-61. The club was led by Cy Young (21-15, 1.99 ERA) but finished a disappointing seventh place. McGuire played the role of pinch-hitter in six games finishing with four at-bats and three hits. In 1908 McGuire continued as manager of the Red Sox with a record of 53-62 before being replaced. He batted in one game, going 0-for-1. Released by the Red Sox, McGuire was signed the following month by Cleveland, played in one game and went 1-for-4.

In 1909, McGuire had another opportunity to manage. He replaced Nap Lajoie, inheriting a .500 Cleveland club and then crawling to a 14-25 record the rest of the way. McGuire did not play in the field in 1909. In 1910 McGuire managed his only full season taking the Cleveland club to a 71-81 fifth-place finish. He caught one game, going 1-for-3. In 1911 McGuire resigned after the club started with a 6-11 record. His reason given to the newspapers was his “desire to give the management an opportunity to secure a manager who may be able to get better results.”13 McGuire did not manage in the big leagues again.

In 1912, apparently having seen his last action as a player, McGuire was signed as a battery coach and scout for the Detroit Tigers under Detroit manager Hughie Jennings, his former teammate from the Brooklyn championship teams. But McGuire played one last game as part of one of the most bizarre games in baseball history.

On a road trip to New York, Ty Cobb was being razzed very harshly by a fan named Claude Lucker (or Luecker). Lucker was disabled in that he was missing all his fingers on one hand and three fingers on the other from an industrial accident. According to Cobb, he had asked both the Highlanders manager and president to have the fan removed.14 Ultimately, Cobb jumped into the stands and viciously beat Lucker. It was widely reported that fans were shouting that the man had no hands. Witnesses claimed that Cobb replied, “I don’t care if he has no legs!”15

AL President Ban Johnson suspended Cobb indefinitely. To the surprise of many, as Cobb was almost universally disliked by his teammates, his team showed unanimous support for their star. They threatened to go on strike in support of more protection for players. Issues came to a head in Philadelphia. Johnson threatened to fine the team $5,000 if the team forfeited its May 18 game against the Athletics. Believing the players were serious and not wanting to go head-to-head with Johnson, Tigers owner Frank Navin told manager Jennings to field a team. The team that got rounded up included college and semipro players — and even a boxer — as well as the coaches and manager. The 48-year-old coach McGuire and 41-year-old coach and former major leaguer Joe Sugden were on the field as players and even manager Jennings pinch-hit. The team was trounced by the defending world champion Athletics, 24-2. The walkout was settled as Cobb encouraged the players to return. Cobb received a fine and ten-day suspension, and the striking players were fined (Navin paid). McGuire went 1-for-2 in his final major-league appearance.

McGuire served as a coach with the Tigers until 1915 (some reports say 1917). His association with the club continued as he served as a scout until he voluntarily retired in 1926. Returning to life in Albion, he coached the Albion College team in 1926. Finally, he retired from baseball altogether.

He retired to a farm on Duck Lake near Albion with his wife. He was reported to have spent his time tending to his chickens and fishing. He never got baseball out of his blood, however, and he continued to follow the game in the sports pages and on radio. In 1936, he was given the 19th gold lifetime pass from Major League Baseball for playing in the majors for more than 20 years. Consistent with the lack of awareness of his accomplishments, he was not given his recognition when the first 17 passes were distributed, as he was not identified as having played 20-plus years. After writing to the National League, his service was verified and he was awarded his pass.

Deacon Jim passed away on October 31, 1936, following several years of illness, a stroke, and finally pneumonia. He was survived by his wife May and brother George. No children were mentioned in his obituaries. Often noticed years later by writers and historians as a statistical marvel of durability including the 26 major-league seasons (tied by Tommy John, surpassed by Nolan Ryan) and playing for 11 teams (since surpassed by Matt Stairs), the consistent and even-tempered Deacon was a leading catcher of his era and its most durable.

Sources

Anderson, Bruce. “A Former Foundry Worker Forged a Record By Playing for 26 Seasons.” Sports Illustrated, August 13, 1984. http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1122416/1/index.htm

baseballreference.com

“Deacon McGuire Resigns” Lewiston Daily Sun. May 4, 1911. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=v7wgAAAAIBAJ&sjid=c2kFAAAAIBAJ&pg=5081,177195&dq=deacon+mcguire&hl=en

McCormick, Mike. “Historical Perspective: Early Terre Haute Baseball, 1867-1889, Part I: Spectators Have a Field Day at the Ballpark.” Terre Haute Tribune Star. August 6, 2000. http://visions.indstate.edu:8888/cdm/singleitem/collection/vcpl/id/10148/rec/2

McCormick, Mike. “Historical Perspective: Organizing a Professional Baseball Team in 1884 (Part I).” News from Terre Haute. July 11, 2009. http://tribstar.com/history/x1048538168/Historical-Perspective-Organizing-a-professional-baseball-team-in-1884-Part-I/print

McNeil, William. Backstop: A History of the Catcher and Sabermetric Ranking of the 50 All-Time Greats. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland and Co., 2006.

Morris, Peter. Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010.

Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Baseball. New York: Penguin, 1997.

Overfield, Joseph M.. “James Thomas McGuire” in Nineteenth Century Stars, edited by Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker, 87. Kansas City: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

Passic, Frank. “Two and a Half Cents Worth.” Morning Star. December 18, 1994, 2. http://www.albionmich.com/history/histor_notebook/941218.shtml

Passic, Frank. “McGuire Brothers Part I. Horsehead Token.” Morning Star. July 9, 1995. http://www.albionmich.com/history/histor_notebook/950709.shtml

Passic, Frank. “McGuire Brothers Part 2.” Morning Star. July 16, 1995. http://www.albionmich.com/history/histor_notebook/950716.shtml

Passic, Frank. “McGuire Brothers Part 3.” Morning Star. July 30, 1995. http://www.albionmich.com/history/histor_notebook/950730.shtml

Passic, Frank. “McGuire Brothers Saloon Was Prominent in Early 20th Century.” Albion Recorder. June 16, 1997, 4.

Passic, Frank. “McGuire Baseball Card.” Morning Star. March 23, 2003, 2. http://www.albionmich.com/history/histor_notebook/030323.shtml

Reisler, Jim. “A Beating in the Stands, Followed by One on the Field”. New York Times (New York, NY), April 28, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/29/sports/baseball/ty-cobbs-outburst-led-to-notorious-game-in-1912.html?_r=0

Smith, Robert. “Of Kings and Commoners,” in The Complete Armchair Book of Baseball: An All-Star Lineup Celebrates America’s National Pastime, edited by John Thorn, Edison, N.J.: Galahad, 2004.

Stump, Al. Cobb. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Algonquin Books 1994.

Notes

1 Bruce Anderson. “A Former Foundry Worker Forged a Record By Playing for 26 Seasons.” Sports Illustrated, August 13, 1984.

2 Joseph M. Overfield. “James Thomas McGuire,” in Nineteenth Century Stars, ed. Robert L. Tiemann and Mark Rucker. Kansas City: Society for American Baseball Research, 1989. 87.

3 Peter Morris. Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero. (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010). 82.

4 Mike McCormick. “Historical Perspective: Early Terre Haute Baseball, 1867-1889, Part I: Spectators Have a Field Day at the Ballpark.” Terre Haute Tribune Star. August 6, 2000.

5 Ibid.

6 Frank Passic. “McGuire Baseball Card.” Morning Star. March 23, 2003. 2.

7 David Nemec. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Baseball. New York: Penguin, 1997. 562.

8 Frank Passic. “McGuire Brothers Saloon was Prominent in Early 20th Century.” Albion Recorder. June 16, 1997. 4.

9 Passic, “McGuire Brothers Saloon was Prominent in Early 20th Century.”

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 “Deacon McGuire Resigns.” Lewiston Daily Sun. May 4, 1911. 4.

13 Al Stump. Cobb (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 1994). 206.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.