Branch Rickey – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Branch Rickey was “a man of strange complexities, not to mention downright contradictions,” wrote the New York Times’ John Drebinger. The great decision to break baseball’s policy of excluding blacks, for which he is justly praised, has, in recent decades, tended to overwhelm the highly negative image he had earned before that decision. He went from “El Cheapo” to moral beacon in just a few years, and richly deserved each characterization.

Branch Rickey was “a man of strange complexities, not to mention downright contradictions,” wrote the New York Times’ John Drebinger. The great decision to break baseball’s policy of excluding blacks, for which he is justly praised, has, in recent decades, tended to overwhelm the highly negative image he had earned before that decision. He went from “El Cheapo” to moral beacon in just a few years, and richly deserved each characterization.

He was deeply religious, sowing Biblical quotations and religious axioms like Johnny Appleseed sowed apple seeds.

He was a tightwad. “Rickey believes in economy in everything except his own salary,” wrote the New York Daily Mirror’s Dan Parker. Daily News columnist Jimmy Powers tagged him El Cheapo after Rickey dumped a number of the Dodgers’ older, and better-known, players soon after taking over.

He was politically and socially conservative. He preached on the temperance circuit as a young man and, as an older man, would regularly attack Communism, Communists, and liberal politicians.

He preached courage and honesty, yet he was devious. Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch dubbed him Branch Richelieu. When a decision by Commissioner Kenesaw M. Landis deprived Rickey of a promising player, he could actively work to subvert the decision through fake transfers. Rickey could “think up many a little scheme that, while not dishonest, still will not leave Rickey & Co. holding the sack on the snipe hunt,” wrote Bill Corum in the New York Journal-American.

He could bring Jackie Robinson to the majors, and tell stories of being deeply moved when an African-American player he coached in college sought to rub off his skin color to escape the prejudices of white America, but he could also relate dialect jokes. He made anti-Catholic remarks at the dinner table and characterize a potential Dodgers purchaser as “of Jewish extraction and characteristics.”

He was articulate, if inclined to overdo the rhetoric and the vocabulary. “Rickey’s natural element is the pulpit,” wrote Red Smith. “He talks with such pontifical oratory that he could and would make a reading of batting averages sound as impressive and as stirring as Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address,” said the New York Times’ Arthur Daley. Players who stumbled out of salary-negotiating sessions were amazed at the verbal rings that had been run around them, and at the salaries they had accepted.

He was absent-minded, often tossing lighted matches into trash cans filled with paper and acknowledging defeat when his five daughters all wound up with fingers next to their noses, the family code that somebody was talking too much. Jane Moulton Rickey, whom he met when she was twelve, proposed to a hundred times, and married at twenty-four, could note, “Mr. Rickey is not, and never has been, one of the ten best-groomed men in America.”

He was fearsomely intelligent, well read, and thoughtful.

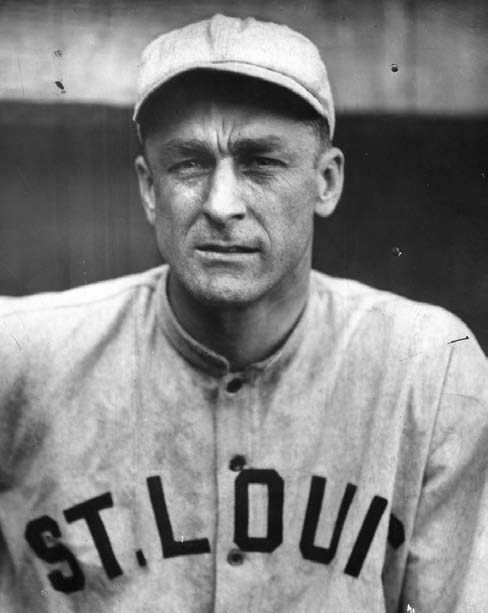

Wesley Branch Rickey was born on December 20, 1881, in Scioto County, on the Ohio River in south central Ohio, to the modest farming family of Jacob Franklin “Frank” Rickey and Emily Brown Rickey. Branch had an older brother, Orla, born in 1875, and a younger brother, Frank, born in 1888. As Branch’s first name would indicate—John Wesley was the founder of Methodism—it was a pious, Methodist household. Rickey finished grade school in Lucasville, Ohio, but then farm labor called. With help from a sympathetic retired educator, he read as widely as the resources of Scioto County allowed in the 1890s. He educated himself enough to become the teacher at the local grade school, saving money for college. Eventually, he went off to Ohio Wesleyan University. For the next decade, Rickey’s life was a welter of sporadic academics, sports, and, eventually, coaching.

He played baseball and football at Ohio Wesleyan and, realizing he could make money to pay for his studies, entered baseball’s semipro summer circuit in 1902 and began to coach the university team the next spring. That summer, he moved to the minor leagues, playing in Terre Haute, Indiana; LeMars, Iowa; and Dallas, Texas. In 1904, after graduation, Rickey returned to Dallas, and was purchased by the Cincinnati Reds near the end of the season.

He spent parts of the next three seasons in the majors, earning a reputation as a marginal catcher, a poor hitter, and an odd duck for refusing to play baseball on Sundays. In Cincinnati, his refusal to play on Sundays infuriated manager Joe Kelley, who released him back to Dallas before he appeared in a league game. For the winter, Rickey moved to Allegheny College, in Meadville, Pennsylvania, where he served as football and baseball coach.

That winter, the White Sox purchased Rickey’s contract, but sent him to the St. Louis Browns after deciding they could not afford a catcher who took Sundays off and would not report until his college coaching duties were done. He made his major-league debut on June 16, 1905. That one appearance was it for the year, as his mother became ill and Rickey went back to Lucasville. By the time she recovered, he went back to Dallas before heading to Allegheny for another year of coaching. There, he became disillusioned with the semiprofessional character of college football and left before the baseball season began.

When the 1906 season did begin, Rickey was back with the Browns. He had his best year that summer, playing in 65 games and hitting .284. The left-handed hitting Rickey had his first major-league safety, a single, on April 23 off Detroit southpaw Ed Killian at Sportsman’s Park. The offensive highlight of his career came on August 6 against the New York Yankees. Rickey hit a two-run homer in the bottom of the second inning to chase Jack Chesbro and extend the Browns’ lead to 5–0. He then hit a “fluke” inside-the-park home run off reliever Walter Clarkson in the sixth, to make the score 6–2. But by the end of the summer his arm was hurting. He returned to Ohio Wesleyan to coach and complete the courses he needed to enter law school. In late winter the shoulder pain returned.

During the offseason Rickey had been sold to the Yankees. Despite a spring training visit to Hot Springs, Arkansas, his arm did not improve. Rickey played sporadically and the league noticed his inability to throw. On June 28, 1907 the Washington Senators stole 13 consecutive bases against him, and Rickey had stopped bothering to throw by the end of the game. It’s a record that stands a century later. Offensively, his average fell to .182 in 52 games. He would make a cameo two-game appearance for the Browns in 1914, but otherwise his playing career was finished. In all, he played in 120 games over four seasons and had a .239 lifetime batting average.

After marrying Jane in Lucasville in June 1906, he had turned to a laundry list of jobs. He was Ohio Wesleyan’s athletic director, while also coaching football, basketball, and baseball. He was secretary of the Delaware, Ohio, YMCA, and he taught beginning law classes even while taking other law classes as a student. As 1908 rolled in Rickey threw himself into William Howard Taft’s campaign for the presidency and the work of the Anti-Saloon League. By the end of 1908, perhaps run down from his schedule, Rickey was diagnosed with tuberculosis, the biggest medical killer of the time.

He spent much of 1909 in a sanatorium in upstate New York, leaving only to begin his first semester at the University of Michigan law school in the fall. By early 1910 his health had improved enough for him to supplement his savings by coaching the university’s baseball team.

In 1911, nearing age thirty, Branch Rickey graduated from law school and chose Boise, Idaho, as the site of his law office. He was, by his own accounts, a miserable failure, gaining one client, who did not even want a lawyer. The impressions he had made as a baseball player and coach came to his rescue. Even while in Boise, he had spent his summer scouting for Robert Hedges, owner of the St. Louis Browns, who had been impressed with Rickey’s intelligence and articulate presentations when he was a player. After his second unsuccessful winter in Boise, Rickey was only too happy to respond to Hedges’ request for a meeting in Salt Lake City to discuss a full-time job with the Browns. He borrowed the train fare from Hedges and began a half-century of life in professional baseball.

Rickey’s initial role was somewhere between scout and general manager. With the help of full-time scout Charley Barrett, Rickey evaluated and tracked players from the Midwest and South. In the winter of 1912 he produced a list of players the Browns could draft from minor-league teams, and thirty of the 105 players chosen that winter were taken by the Browns. By mid-1913 Rickey was the field manager of the Browns. He began teaching his players with a blend of lectures, heart-to-heart talks, and drills. He also began his lifelong fascination with statistical analysis, hiring a young man to sit behind home plate and keep track of how many bases each player made for himself and advanced his teammates. The team improved in 1914, but slid back in 1915 amid accusations that Rickey was too intellectual in dealing with his players.

That winter Hedges sold the Browns to Phil Ball, after granting Rickey a long-term contract. Ball, however, was contemptuous of Rickey’s religious views and his approach to the game. He brought in Fielder Jones as field manager while Rickey chafed in his former role of finding players for the Browns. By the spring of 1917 a new ownership group for the National League’s St. Louis team persuaded Ball to let Rickey out of his contract to become the Cardinals’ president.

While he was still in St. Louis with his growing family, running the Cardinals was not a dream job. The new ownership was undercapitalized. The team had finished in the top half of the league once in the previous quarter-century. Rickey and Cardinals manager Miller Huggins clashed over Rickey’s “theoretical” approach to the game. The 1917 Cardinals struggled to their best record since 1891, but it was good only for third place. After the season, Huggins was lured away by the New York Yankees, and Rickey hired Jack Hendricks to take his place.

In August 1918 Rickey joined the Army Chemical Corps, then a new field with cachet. He was commissioned a major and joined a unit with Captains Ty Cobb and Christy Mathewson. In the weeks leading to the November 11 armistice, Rickey’s unit supported a number of American attacks on the Germans. He was back in the United States on December 23 and in Lucasville with the family for Christmas.

The Cardinals team he returned to was in serious financial trouble. Rickey borrowed Jane’s family heirloom rugs to make his barren office look respectable, and made himself manager to save a salary. But he was building the foundation that would make the Cardinals a dominant team for the next three decades.

The Cardinals team he returned to was in serious financial trouble. Rickey borrowed Jane’s family heirloom rugs to make his barren office look respectable, and made himself manager to save a salary. But he was building the foundation that would make the Cardinals a dominant team for the next three decades.

Rickey’s record as manager of the Cardinals was mediocre. For his first three years, he increased the win totals each year, and the Cardinals reached third place by 1921. But in 1922, the team slipped to fourth, then fifth, then sixth, before he was replaced early in 1925. Angry and humiliated, he contemplated quitting, but eventually decided to remain as general manager. For those who questioned Rickey’s ability to lead and motivate players, they had their prejudices confirmed when Rogers Hornsby took the Cardinals to the 1926 pennant.

While the critics savaged Rickey as a manager, no one doubted his abilities in the front office. It was only when Rickey was kicked upstairs from the Cardinals’ dugout that he found his true role. “Rickey practically created the office of business manager as it is understood today,” wrote the New York Times’ John Drebinger in 1943.

Rickey’s first great innovation was the farm system. “When the Cardinals were fighting for their life in the National League, I found that we were at a disadvantage in obtaining players of merit from the minors,” Rickey said. “Other clubs could outbid. They had money. They had superior scouting machinery. In short, we had to take what was left or nothing at all . . . .Thus it was that we took over the Houston Club for a Class A proving ground in 1924 . . . Still, I do not feel that the farming system we have established is the result of any inventive genius – it is the result of stark necessity. We did it to meet a question of supply and demand of young ballplayers,” he told The Sporting News’ Dick Farrington.

The Cardinals eventually created a chain of minor-league teams so they could sign players cheaply, winnow the good from the great, win pennants, and make money. Rickey would sell the good to others and keep the great for the Cardinals.

Rickey proved a cold-blooded judge of talent, and a man with the knack for nurturing what talent he had. He was not the sentimentalist to hang on to an aging player who had contributed greatly to the team’s past success. It is better to trade a man a year too early than a year too late, he preached. He created the concept of the “anesthetic ballplayer,” the one who is good enough to be a major leaguer, but not good enough to help win a pennant or a World Series. Trading the anesthetics and the fading stars filled holes the farm system could not. And in the minors, Rickey was an innovator not just in creating, but in teaching.

He came up with sandpits to teach players to slide; a set of strings to define the strike zone and help pitchers with their control; the batting tee to help hitters hone their swings, and chalk talks. After World War II, when Rickey was with the Dodgers, he expanded on the statistical analysis he had first tried with the Browns. He hired Allan Roth, who charted where Dodgers batters’ hits fell.

Rickey was observant in a way that amazed even other baseball men. There was the story of one pitch—a foul ball—while Rickey was sitting behind the plate one day. After the pitch he turned to an aide and dictated the following notes: The center fielder had failed to get a jump on the ball, the pitcher had an unbalanced motion and would not be able to field his position, and the catcher had blinked as the batter swung, causing him to miss the foul tip.

Rickey’s player-evaluation skills built the Cardinals’ machine that dominated the National League, winning nine pennants and six World Series between 1926 and 1946. This machine, built on the ownership of minor-league clubs, did not run smoothly. Baseball commissioner Kenesaw Landis did not like to see minor leagues or teams run simply as talent suppliers for the major leagues. He wanted them to act as independent businesses. He wanted players to have the fullest freedom to exploit their talent, and not get stuck in the minor-league systems of talent-rich organizations. Rickey, whose plan had been followed by the other major-league teams, argued that major-league ownership had allowed the minor leagues to survive the Depression of the 1930s.

In 1938, in what became known as the Cedar Rapids decision, Landis freed at least seventy-four Cardinals farmhands. Landis found that the Cardinals had relationships with more than one team in some leagues, meaning it could affect pennant races by moving players between these teams. He offered no evidence that they had done so. The one released player of unusual talent was Pete Reiser, and Rickey set out to subvert Landis’s decision by making sure his protégé, Larry MacPhail of the Brooklyn Dodgers, picked up Reiser with a promise to return him to the Cardinals once the hullaballoo calmed down. Reiser, however, performed so well in spring training that press and public pressure to keep the young outfielder led MacPhail to renege on his promise.

In public, Rickey’s reputation as a shrewd executive and motivational speaker grew. He was asked to speak often, and was never afraid to tie his conservative religious and political beliefs with his baseball success. He befriended political figures, usually conservative Republicans. He was approached to run for governor of Missouri. He was described as one of Republican presidential candidate Thomas Dewey’s closest friends and supporters and touted as his successor as New York governor if Dewey was elected president.

By late 1942 Rickey’s relations with Cardinals owner Sam Breadon had become strained. The two were fighting over Rickey’s bonus payments and Breadon’s dismissal of Rickey protégés in the farm system. Rickey reportedly was upset at Breadon’s refusal to back him over the Cedar Rapids decision and with Breadon’s paying a large bonus to himself while cutting Rickey’s budget for salaries. Rickey was considering a top executive post with a large insurance company.

In 1937, when Brooklyn Dodgers board member James Mulvey had first approached him, Rickey had not been prepared to leave a comfortable life in St. Louis. By late 1942 he was. The wooing was relatively quick. The New York Times first reported Brooklyn-Rickey talks on October 4, 1942. The move was announced on October 29, a day when Rickey was introduced as the new general manager at a lunch at the Brooklyn Club. At that lunch Rickey also was introduced to Walter O’Malley, a thirty-nine-year-old lawyer who shared the Brooklyn Trust table with him.

In Brooklyn Rickey saw a different team than the press and the fans. The fans and the reporters saw the 1941 pennant winner and a 1942 team that had finished second. Rickey saw a team that was old, with a roster about to be ravaged by the needs of military service. It was the disposal of aging stars that earned him the nickname El Cheapo. It was his response to World War II that would build the foundation of the Boys of Summer.

With the draft in place most teams cut back on signing players, bowing to the uncertainties of wartime. In response the number of minor leagues shrank to ten in 1944 from the forty-one of 1941. Rickey simply figured the war would end some day and he signed talent in buckets, seeking to repeat his success in building the Cardinals’ minor-league system. Players like Gil Hodges would make token appearances in the Major Leagues before disappearing into boot camp, then emerge after the war to stock baseball’s richest farm system. Rickey earned another nickname, “The Mahatma,” after sportswriter Tom Meany read a portrait of Indian political leader Mohandas “Mahatma” Gandhi that described Gandhi as a combination of “your father and Tammany Hall.”

In the years immediately after the war, Rickey blended prewar players like Dixie Walker, Hugh Casey, and Pee Wee Reese with the results of his player-development program. That program had led to another Rickey innovation—the spring training complex. With more than 700 players under contract, the Dodgers needed a large facility if they wanted to insure uniform training and easy analysis of their prospects. In 1947, Rickey struck a deal with the town of Vero Beach, Florida, for the use of the former U.S. Navy pilot-training base on the west edge of town. Using a complex system of colors and numbers, the minor leaguers were sorted, trained, analyzed, graded, and eventually assigned to their minor-league teams, all according to the Rickey methods.

Except for the Vero Beach facility, which would become a model for other teams, the methods were those Rickey had developed with the Cardinals. But in Brooklyn, he took another step, one that would raise him from talented baseball executive to sainted agent of progress.

Rickey’s decision to seek black baseball talent came fairly soon after he joined the Dodgers. His pursuit of black players was a typical combination of motives and methods. It was a product of his religious beliefs; of his desire to win and draw fans; and of his ability to see baseball in the context of American society. It was conducted not by looking for just the best baseball talent, but for the best combination of on-field talent, maturity, and intelligence. For his African American torchbearer, he chose a college-educated man who would be twenty-seven before he played even one game in the white minor leagues. He chose Jackie Robinson in part because he was from California, in whose milder racial climate he had played most of his life on integrated athletic teams. Rickey encouraged him to marry his fiancée, a move he felt always helped a ballplayer’s career. Robinson went on to justify Rickey’s gamble in every way and cement a lifelong relationship between the two men.

But his relationships with his partners were not so strong. By 1950, Rickey knew his lucrative contract would not be renewed and he began the steps that would put Walter O’Malley in control of the Dodgers and himself at the general manager’s desk in Pittsburgh.

In Pittsburgh Rickey set out to build the kind of dominant organization he had constructed in St. Louis and Brooklyn. Rickey’s one original move in Pittsburgh came too late to save him. In 1955, he sent Howie Haak, his best scout, to begin scouring the Caribbean for talent. This move would bear immense fruit for the Pirates in the 1960s, but by then Rickey was gone

After the 1955 season Rickey stepped down as general manager, saying he would spend the rest of his ten-year contract as a senior consultant to the team. But it was clear that consulting was a cover for being at loose ends, a situation that did not change until late in 1958, when Rickey began talking with a New York lawyer named William Shea. In the wake of the Dodgers’ and Giants’ departures for the West Coast, New York City Mayor Robert Wagner, Jr. had asked Shea to head an effort to bring National League baseball back to New York. Shea turned for advice to George V. McLaughlin, a New York banker and civic luminary who had brought O’Malley to the Dodgers in 1940. McLaughlin suggested that Shea talk to Rickey. Rickey, who had apparently been mulling the idea for a while, suggested a third league.

For the next two years, Rickey headed the Continental League. He wooed ownership groups, promised his league would find players even while honoring major-league baseball’s reserve clause, and worked through Congress to bring pressure to limit the Major Leagues’ control of their players. The league collapsed in late 1960, when both the National and American leagues committed to expansion.

For two years he puttered, but then jumped at a chance to return to the Cardinals as a “senior consultant.” It was an awkward relationship. General manager Bing Devine felt threatened by owner Gussie Busch’s hiring of Rickey. Rickey’s opposition to a trade that brought shortstop Dick Groat to the Cardinals worsened the situation. And when a strongly worded memo urging Stan Musial’s forced retirement leaked to the press, Rickey’s status became fragile. He was not helped when Busch decided to fire Devine in mid-1964, a move that was interpreted as interference by Rickey. The move embarrassed Busch as the Cardinals rallied to win the pennant with a team Devine had assembled. After the World Series, won by the Cardinals, Busch fired Rickey as well.

In 1965, Rickey finished his work on The American Diamond: A Documentary of the Game of Baseball, the closest thing to an autobiography Rickey would do. It contained portraits of a group Rickey called the sports immortals, as well as reflections from his years in the game.

He died on December 9, 1965, and was buried in Rushtown, Ohio, just across the Scioto River from Lucasville. Jane Rickey died on October 16, 1971, and is buried next to him.

This essay was originally published in “The Team That Changed Baseball and America Forever: The 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers” (University of Nebraska Press, 2012), edited by Lyle Spatz. It also appears in “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles F. Faber.

Sources

Current Biography 1945, p. 497.

Polner, Murray. Branch Rickey: A Biography. New York: Atheneum, 1982.

Chamberlain, John, “Brains, Baseball, and Branch Rickey,” Harper’s, April, 1948.

Dexter, Charles, “Brooklyn’s Sturdy Branch,” Collier’s, September 15, 1945.

Fitzgerald, Ed, “Sport’s Hall of Fame: Branch Rickey, Baseball Innovator,” Sport, May 1962.

Holland, Gerald, “Mr. Rickey and the Game,” Sports Illustrated, March 7, 1955, p. 38.

Rice, Robert, “Profiles: Thoughts on Baseball. Two parts, The New Yorker, May 27 and June 30, 1950.

Farrington, Dick, “Branch Rickey, Defending Farms, Says Stark Necessity Forced System,” The Sporting News, December 1, 1932, p. 3.

The Branch Rickey Papers at the Library of Congress.

This essay was originally published in Lyle Spatz, ed. The Team That Changed Baseball and America Forever (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012).