Pepper Martin – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

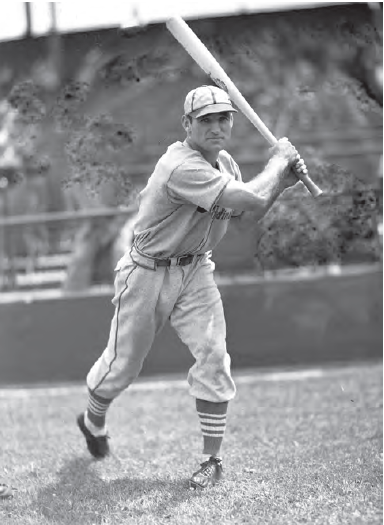

The only thing a team with players named Dizzy, Ducky, and Daffy needed to become truly legendary was a dash of Pepper. And that’s exactly what the famed Gas House Gang St. Louis Cardinals got in their sparkplug extraordinaire, Pepper Martin.

Johnny Leonard Roosevelt Martin was a leap-year baby, born February 29, 1904, in Temple, Oklahoma, 120 miles south of Oklahoma City. He was the youngest of seven children born to Celia Spears Martin and George Washington Martin. The Martins struggled to make ends meet as cotton farmers, forcing Johnny to learn very early on that everything he got in life would come only through hard work. Even as a boy he worked with his brothers and sisters tending the family livestock. Despite the presence of animals on the farm, meals often didn’t offer much variety.

“In lean times the family ate cornmeal mush and fried mush, too,” wrote Martin biographer Thomas Bartel. “Beans and cabbage, bought by the hundred-pound sack, supplied much of the family diet.”1

The family moved to Oklahoma City in 1910 after the farm was ruined by a drought. Their financial circumstances didn’t improve very much, and in those days this meant that Martin often had to leave school and work to contribute to the family income. He delivered newspapers, getting up at 3:30 in the morning to deliver the Daily Oklahoman, but before beginning his appointed rounds, he caught up on major-league box scores during the summer, and read about offseason goings on in the winter. In the afternoon he delivered another paper, The News. Eventually, he saved up to buy what became one of his prized possessions, his first baseball glove.

“Not so many kids in my neighborhood had gloves and owning that mitten gave me almost as much happiness as would a couple of home runs in a World’s Series game,” Martin said.2

Pride in ownership aside, Martin’s frequent absences from elementary school delayed his graduation until he was 15 years old, in 1919. He went to high school in the next year, but quit again to make deliveries for the Mistletoe Shoe Company at $12 per week. After a brief return in 1921, he quit school for good, “to earn money instead of fiddling around and getting an education.”3

Most of Martin’s early experience as a ballplayer was in the Oklahoma City sandlots with various club and company teams. He first played organized ball for the Second Presbyterian Church (Martin was a Baptist) in 1921as a pitcher. Over the next few years he also played for the Brooks Hardware Company, Kelley Jewelry, the Oklahoma Gas and Electric Company, and even the Oklahoma National Guard (the latter arrangement ended when Martin didn’t join the outfit).

Martin’s athletic endeavors weren’t restricted to the baseball diamond. In the early 1920s (accounts differ as to which years), he played halfback for the Hominy Indians, a popular and often powerful team during the Jazz Age that was backed by members of the Osage Native American tribe that had gotten wealthy due to the Oklahoma oil boom.4

But baseball was Martin’s first love and he finally got into the professional ranks in 1924, when a friend named Cliff Campbell put in a word for him with the Guthrie team in the Oklahoma State League, a circuit that was teetering on the edge of extinction. The Guthrie franchise moved twice before the league finally disbanded in July of that year. The league’s demise was a blessing in disguise for Martin, because he went to a Cardinals tryout camp in Greenville, Texas, where St. Louis had a team in the Class D East Texas League. The Cardinals signed him on July 10, 1924, and paid Guthrie $300 for him. Martin appeared in 27 games as a pitcher and center fielder for the Greenville Hunters. He hit a respectable .274 and had a 1-1 record.

Martin started the 1925 season in Greenville and while he continued to pitch and play the outfield, his primary position was second base. He pasted the ball at a .340 clip in 98 games, with 18 home runs and 38 stolen bases, and the Cardinals promoted him to Fort Smith (Arkansas), their team in the Class C Western Association. There he showed he could handle higher-level pitching, batting .344 the rest of the season. Fielding was another issue. Playing shortstop, Martin committed 21 errors in 203 chances for an .897 fielding percentage.

It was in Fort Smith that John Martin became “Pepper” Martin, although the exact origin is not clear. He is quoted as saying that team owner Blake Harper began calling him Pepper after watching him run the bases and “listening to my line of chatter.”5 In another version, Martin arrived in Fort Smith and saw the headline “Pepper Martin to Join Twins.” Angry at the headline, Martin stormed down to the newspaper office to complain, only to see Harper there and be told that Harper had picked out the name.6 Harper may have borrowed the nickname from Vincent “Pepper” Martin, a prominent featherweight and junior lightweight boxer of the time. Whatever the origin, the moniker stuck.

Despite his adventures in fielding, Martin’s hitting earned him a spot with the Syracuse Stars of the Double-A International League (there was no Triple-A designation at that time). When it came time to go to from Oklahoma to spring training in Greenwood, South Carolina, he cashed the check that was supposed to pay for his train ticket and rode the rails like a hobo to his destination.

After not bathing for several days while en route, Martin was rather stinky when he arrived in camp. That was somehow appropriate because the Syracuse club’s play that season could be described much the same way, as its 70-91 record will attest. Martin duplicated his good-hit, no-field results from the previous season; he batted .300, but he committed 35 errors in 88 games at second base. Cardinals management evidently felt the leap from Class C to Double-A was too much for Martin and demoted him to the Houston Buffaloes of the Class A Texas League in 1927 for more seasoning and to learn how to play the outfield.

Offensively, Martin continued peppering the ball to the tune of a .306 average and eight home runs, and had a .963 fielding percentage as an outfielder. His numbers impressed Cardinals brass enough to win him a spot on their major league roster for the 1928 season.

Once Martin got to the big leagues, however, it seemed the Cardinals didn’t know what to do with him. He appeared in only 39 games all season, including just 16 plate appearances, with all but one being pinch-hit appearances. He played only four games in the field, and was used as a pinch-runner 21 times. He did get his first taste of World Series action that year as a pinch-runner in Game Four against the New York Yankees. He scored a ninth-inning run, but it was of little use; it was in the game in which Babe Ruth hit three home runs in leading the Yankees juggernaut to a 7-3 victory and a sweep of the Redbirds.

Since Martin wasn’t getting playing time in the major leagues, he was better off returning to the minors, and that’s exactly what he did, being sent to Houston in 1929. He played a full season there, batted .298, and captured the fans’ fancy.

“The fans of Houston voted Johnny the most popular player on the team,” said his wife, Ruby. “He was given a Chevrolet coupe for a prize.”7

As popular as Martin may have been with the Houston fans, the Cardinals still didn’t think he was ready to rejoin the big club. They did, however, promote him to Rochester for the 1930 season. Unlike his previous sojourn in Double-A, he left no doubt this time about his abilities by hitting .363, with 20 home runs and 304 total bases. The major-league career, and the legend, of Pepper Martin were about to begin in 1931.

Martin was essentially a 27-year-old rookie when he donned a Cardinals uniform during the spring of 1931. The Cardinals won the National League pennant going away that year; they won 101 games and were 13 games ahead of the second-place New York Giants by season’s end. Martin made a substantial contribution with a .300 batting average, 75 RBIs, 68 runs scored, and 16 stolen bases, but it was in that year’s World Series that he really shone.

The Cardinals’ opponent in the fall classic was the two-time defending champion Philadelphia Athletics, the last great team Connie Mack ever had. The Cardinals knew how formidable the A’s were, having lost to them in the previous year’s Series in six games. The 1931 Series was a back-and-forth affair, as neither team held more than a one-game advantage at any time. Martin proved the difference between winning and losing for the Cardinals when he tied a Series record (since broken) with 12 hits, and batted .500 with one home run, five RBIs, and five stolen bases. If they had a World Series MVP in those days, Martin would have won it hands down.

Martin’s outstanding World Series performance made him a household name and after the Series was over he embarked on a vaudeville tour at $1,500 per week, an outstanding salary in Depression-era America. The great salary notwithstanding, he quit the gig after just four weeks, saying, “I ain’t no actor, I’m a ballplayer.”8

Before the 1932 season, Martin had this to say about baseball fans’ expectations: “One day they holler for you to take off your cap; the next say they yell at you to take off your uniform.”9 All the Cardinals probably heard a lot of yelling that season season as an injury-plagued Martin appeared in only 85 games and batted .238 with only 34 RBIs, both career lows, and the team plummeted to sixth place with a 72-82 record.

Still, the season was significant for Martin in two respects. First, manager Gabby Street decided to experiment by moving Martin from center field to third base in early September once it became apparent that the Cardinals weren’t going to win the pennant. It ended up being his primary position for the next three seasons. Second, a young pitcher named Jay Hanna Dean, or Jerome Herman Dean (depending on which day of the week you asked him), known to all as Dizzy, joined the team. Dean’s arrival gave Martin a partner in crime for stunts considered humorous among players of that era.Their teammate Leo Durocher related a story about how Dean and Martin pulled a gag involving a society women’s luncheon at Philadelphia’s elegant Bellevue-Stratford hotel, where the team was staying:

What Pepper did first was to go to a trick store for a handful of smoke bombs. What he did next was to go down to Wanamaker’s (department store) with a couple of the others to buy firemen’s uniforms. The lunch hour ended, the dowagers filed out into their cars and from there it was nothing except explosions and smoke and jumping hoods. The women went running back into the dining room in panic to mix with the women who were trying to leave and a whole new group that was trying to get in. In the middle of all this pandemonium, Pepper and his crew arrived in their firemen’s uniforms to enforce the fire regulations. Well, they had women moving from one table to the other, they had three women standing up here and five others sitting down there. They had the manager and the captains running all over the place.10

Durocher gives us other insights into Martin that may fall into the “too much information” category, such as that he never wore underwear or a “protective cup” when playing.

“God apparently watches over drunks and third basemen who play without any protective gear,” wrote Durocher. “Pepper must have been hit in every other portion of his body at one time or another except the crucial one.”11

When Martin wasn’t causing chaos in fancy hotels, he was having a string of some pretty productive years at his new position, beginning in 1933. He hit .316 and led the league in runs scored (122) and stolen bases (26), which he pilfered using a head-first slide that Durocher claimed he invented.12 Martin was also the very first batter in the very first All-Star Game, at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Gabby Street’s experiment of having Martin play third base was unsuccessful from a defensive standpoint, as Martin was second in the league in errors by a third baseman with 25. But overall, his improved productivity helped the Cardinals rebound from their bad 1932 season, and although they finished fifth, their 82-71 record set the table for the famous 1934 season.

The Gas House Gang, as the Cardinals were nicknamed in 1934, were seven games behind the New York Giants on September 6, but roared back to win the pennant by two games. They went on to defeat the Detroit Tigers in seven games in the World Series. Injuries limited Martin to 110 games that season, but he nonetheless repeated as stolen-base champion (23) and as an All-Star, even though his average dipped to .289. His performance in the fall classic didn’t quite measure up to the standard he had set three years earlier, but it was still impressive: 11 hits, a .355 batting average, 4 RBIs, and 8 runs scored.

Martin made his third consecutive trip to the All-Star game in 1935, and his average improved to .299, although he lost his stolen-base crown to Augie Galan of the Chicago Cubs (Galan had 22, Martin had 20). He was second on the team in runs scored with 121, 11 behind team leader Joe “Ducky” Medwick.

Martin regained the stolen-base title in 1936 in what turned out to be has last complete season in the major leagues. He pilfered 23 bags, drove in a career-high 76 runs, batted .309 and scored 121 runs for the second year in a row, yet he was not chosen for the All-Star team. It is possible that his switch to right field from third base may have been the reason because the right fielders on the National League All-Star team were Frank Demaree of the Cubs and Mel Ott of the Giants. Both those players had superior power numbers: Demaree hit 16 home runs and drove in 96 runs, while Ott led the league with 33 homers and 135 RBIs.

The 1937 season got off to a good start for Martin. He was hitting .317 around the time of the All-Star Game, and regained a berth on the National League team.13 Then he suffered a serious knee injury in August and ended up playing in only 98 games for the season.14

Martin, in fact, never appeared in that many games again. Between 1937 and 1940, he averaged 91 games per season and never did appear again in the World Series.

While injury reduced his playing time, Martin found other ways to stay productive. One of them was the formation of his Mississippi Mudcats band, with teammates Lon Warneke (guitar), Bill McGee (violin), Lefty Weiland (jug), outfielder Frenchy Bordagaray (washboard, auto horns). The band played real ol’ down-home country music, and was even good enough to appear on radio.15 Their repertoire included such classics as “They Buried My Sweetie Under an Old Pine Tree.”

Martin retired after the 1940 season to become manager of the Sacramento Solons, the Cardinals’ affiliate in the Pacific Coast League. He managed in the minors for 13 seasons with several teams from as low as Class B all the way up to Triple-A. He interrupted his managerial career in 1944 to play 40 games in the outfield for the Cardinals in the manpower-depleted World War II season. After that he returned to managing in the minor leagues, except for a stint as a coach with the Cubs in 1956.

Martin’s managerial career reached a low point in 1949 when he choked an umpire while piloting the Miami Sun Sox of the Class B Florida International League, and was suspended for the remainder of the season. The Sun Sox were playing the Havana Cubans in Havana on August 26 when a rhubarb erupted after a decision by base umpire W.E. Williams on a close play. In the ensuing argument, Williams ejected Sun Sox second baseman Knobby Rosa and when Rosa refused to leave, chief umpire Clem Camia declared the game forfeited. Martin became a manager gone wild, went after Camia and started choking him until police pulled Martin off.

The suspension was handed down on September 1, with less than a week to go in the season, causing Martin to miss only five games. He was back in the manager’s chair in 1950.16

Martin’s high point came in 1953 when he led the Fort Lauderdale Lions to a first-place finish, with a 92-46 record, 14 games ahead of the St. Petersburg Saints. The Lions went on to win the league championship in six games over St. Petersburg.

Martin was a Renaissance Man of sorts, and not just for his ability playing what he called the “gittar.” He was in the fight game as co-manager of a boxer, played basketball for the House of David basketball team, served briefly as a placekicker for the National Football League’s Brooklyn Dodgers, and was an avid outdoorsman.

In 1961, after he had left Organized Baseball, Martin worked as the athletic director for the Oklahoma State Penitentiary, where he coached the prison’s baseball team, and, presumably, taught his players how to steal.

Martin died on March 5, 1965, at the age of 61 in McAlester, Oklahoma, from a heart attack he had suffered the night before at his ranch in Blocker. His wife, Ruby, and three daughters, Alyne, Jennie and Alice, survived him.

Sources

Barthel, Thomas, Pepper Martin: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2003).

Durocher, Leo, with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975).

Pittsburgh Press, March 3, 1932

Milwaukee Journal, October 22, 1938

The Independent, (St. Petersburg, Florida), September 2, 1949

The Sporting News, March 20, 1965

baseball-reference.com

baseball-almanac.com

Notes

1 Thomas Barthel, Pepper Martin: A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2003) 5-6.

2 Barthel, 7.

3 Barthel, 10.

4 The inscription on a bust of Martin at Redhawk Ballpark in Oklahoma City attributes the nickname “Wild Horse of the Osage” to his time as a football player for the Hominy Indians (waymarking.com/waymarks/WMAYAC_John_LR_Pepper_Martin_Oklahoma_City_OK). An article in the Miami News, April 9, 1959, credits the nickname to the Cardinals’ trainer, who thought it up during the 1931 World Series.

5 Barthel, 19.

6 Ibid.

7 Walter W. Smith, “’Pepper’ Martin Hero to his Wife,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 10, 1931.

8 Joe Reichler and Ben Olan (Associated Press), “Pepper Gallops to National Fame,” Tuscaloosa News, January 26, 1961.

9 “Pepper Martin Unspoiled by World Series Fame,” Pittsburgh Press, March 3, 1932.

10 Leo Durocher with Ed Linn, Nice Guys Finish Last, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975), 91.

11 Durocher, 89.

12 Durocher, 82.

13 Edgar G. Brands, “All-Star Tilt to Test N.L. Hurling Against A.L. Bats,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1937.

14 Red Byrd, “Cards’ Bubble Pops on Dizzy’s ‘Bursitis,’” The Sporting News, September 2, 1937.

15 “Radio: Programs Previewed: September 5, 1938,” Time, September 5, 1938.

16 Associated Press, “Pepper Martin Suspended Rest of Season for Choking Umpire,” The Independent (St. Petersburg, Florida), September 2, 1949.