Jim Piersall – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

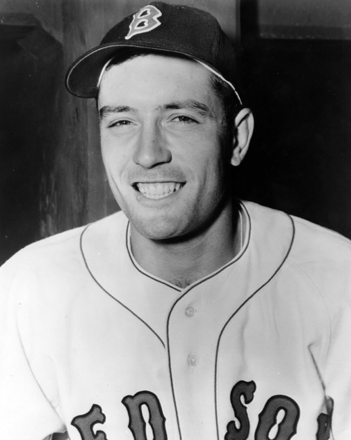

Jimmy Piersall played 20 years of professional baseball, including parts of 17 in the major leagues. He is best known for his nervous breakdown and hospitalization during his rookie season of 1952, an ordeal that led to a best-selling autobiography and two movies. Few could have imagined in 1952 that Piersall would have 15 years of high-level baseball left in him, seasons filled with colorful incidents and episodes, or that he would be employed in baseball for 20 years after that. Whether he was arguing with an umpire, yelling at opposing players from the bench, hiding behind a monument in Yankee Stadium, or running the bases backwards, Jimmy Piersall made baseball fun for many years.

Jimmy Piersall played 20 years of professional baseball, including parts of 17 in the major leagues. He is best known for his nervous breakdown and hospitalization during his rookie season of 1952, an ordeal that led to a best-selling autobiography and two movies. Few could have imagined in 1952 that Piersall would have 15 years of high-level baseball left in him, seasons filled with colorful incidents and episodes, or that he would be employed in baseball for 20 years after that. Whether he was arguing with an umpire, yelling at opposing players from the bench, hiding behind a monument in Yankee Stadium, or running the bases backwards, Jimmy Piersall made baseball fun for many years.

Piersall was born on November 14, 1929, in Waterbury, Connecticut, a factory city about 30 miles southwest of Hartford. His father, John, was a house painter who struggled to stay employed during the difficult 1930s. His mother battled mental illness for most of Jimmy’s childhood, often residing an hour to the east in Norwich State Hospital. Piersall had a brother who was much older and not a part of Jimmy’s childhood. Although Piersall later criticized the depiction of his father (played by Karl Malden) in the better known of the movie versions of his life, Piersall wrote in his own autobiography that he loved but feared his father, who hit him with a strap when he misbehaved or did not do as he was told.

Even when Jimmy was a young child, his father dreamed of a professional baseball career for his son. No other activities—sports, jobs, social events—were allowed to interfere with baseball practice, whether it was with his team or a workout with his father. Jimmy played for Sacred Heart elementary school and Leavenworth High, and in high-level amateur leagues, always an outfielder, and was playing in semipro games by the age of 13. His father would not let him play football, fearing injuries, but Jimmy became a legendary local basketball player. In his senior season, he made all-state and all-New England, and led his team to the 1947 New England title at Boston Garden, scoring 29 of his team’s 51 points in the final.

Piersall was, by his own accounts, very high-strung even as a child, beset by headaches beginning as a teenager. He could not sit in one place for long, could not read a book, yet he could not leave any task unfinished. He spoke and moved constantly, which drove some of his peers crazy. He yelled instructions nonstop in basketball and baseball, and argued with officials often. He was not allowed to play football, but instead was in charge of the yard markers for his high-school team, which allowed him to yell instructions at the players from close by. When he wasn’t fidgeting or talking, he was worrying—about his father, his mother, his playing abilities, his future.

After graduation, he joined the Meriden International Silver Company semipro team, playing five days a week and mulling over his options. Besides many college offers–including a basketball and baseball scholarship to Duke–he spoke with scouts from many major-league teams, working out in both Yankee Stadium and Fenway Park. Teams at the time were restricted to giving bonuses of no more than $6,000 unless they put the player on the major-league roster the next year. Piersall got many offers, but eventually signed with Neil Mahoney of the Red Sox. “I had no intention of signing with the Yankees,” Piersall recalled later. “Waterbury is a Yankee city, but I was a Red Sox boy. I wouldn’t have given my Yankee friends at home the satisfaction of signing with their team.”

Piersall began his career in 1948 playing for Mike Ryba at Scranton of the Eastern League, hitting .281 with 12 home runs in 141 games. Playing his usual center field, Piersall hit sixth in the order and led the league with 92 runs batted in. This earned the 19-year-old a 1949 promotion all the way to Louisville, the Red Sox’ top affiliate, in the American Association. He played two full seasons there, hitting .271 and .255, while honing his reputation as a defensive star. After the 1950 season, Ryba, now managing at Louisville, said, “Piersall is going to be a great center fielder.”1 Piersall got into six games with the Red Sox in late September 1950, getting two hits in seven at-bats. His first hit was on September 27, a single off Senators pitcher Gene Bearden.

While in Scranton, Piersall met Mary Teevan, with whom he quickly fell in love. After the 1948 season, Piersall returned home, but he and Mary visited each other often over the winter and the next year while he was in Louisville. The two married on October 22, 1949, in Scranton, and began having children almost annually—eventually raising nine. A new family also brought new stress and worry for Piersall.

In late 1950, the couple and Jimmy’s parents moved into a brand-new house in Waterbury, and Mary bought new furnishings to fill the house. After living in the house for three days, Piersall was so overwhelmed with doubts about this new situation that he demanded that everyone move out—the parents moved back to their old house, Jimmy and Mary moved in with her family in Scranton, and the new house and all its new furnishings were sold. Mary later recalled this incident as an early indication of the larger problems ahead.

Meanwhile, Piersall was building his baseball career. He made the Red Sox in 1951 but did not play and asked to be sent back to Louisville. He hit .310 in 17 games there, but a logjam of outfielders caused his demotion to Birmingham (Southern Association). He responded with 15 home runs and a .346 average in 121 games, making the midsummer all-star team. Birmingham won the league playoffs with four-game sweeps over Mobile and Little Rock, and then beat Houston, the champion of the Texas League, in the annual Dixie Series, in six games. Piersall hit .476 against Houston. He was recalled by the Red Sox afterward, but did not play.

In early 1952, the Red Sox instituted a winter instructional school for youngsters at their spring training base in Sarasota, beginning a month before spring training. The club invited 35 prospects, among them Piersall, Dick Gernert, Ted Lepcio, Faye Throneberry, and Tom Umphlett. Red Sox manager Lou Boudreau and his staff ran the camp. The players practiced running bases, playing each position, sliding, pitching, and hitting. Surprisingly, Boudreau played Piersall at shortstop in Sarasota. Boudreau and general manager Joe Cronin, each a former all-star shortstop, worked with Piersall and were excited by what they saw. At the team’s regular training camp, Piersall played both infield and outfield, as Boudreau experimented with several people at new positions. By all accounts, Piersall played well.

A national story written about Piersall’s shortstop switch in early 1952 referred to the rookie as “high strung,” “spirited,” and “voluble,” and as someone who tended to “press too hard.”2 Prophetic words, it would turn out. Nonetheless, on Opening Day in Washington, Piersall took his place at shortstop. Piersall was a sensation with the fans—he clowned with them, made goofy gestures, ran in circles, and imitated opposing players. For a while most people laughed. The behavior first turned problematic on May 24, in a fight with Yankees infielder Billy Martin, at whom Piersall had been screaming insults. Later that same day he scuffled with teammate Mickey McDermott, who had apparently been teasing him about his earlier fight. Piersall battled with umpires constantly, being ejected from games three times early in the season. In mid-May, hitting .255 and fielding erratically, Piersall was benched. Vern Stephens’ hot hitting kept Piersall out of the lineup, though his antics continued.

On June 5, Piersall was given a chance as the right fielder, and responded by hitting .368 between June 6 and June 15 and playing great defense. But his clowning grew more outrageous. He let opposing infielders know he was bunting by pantomiming bunt attempts. If the bullpen cart drove by him in the outfield he stuck out his thumb to hitch a ride. He laughed with fans, made fun of his own mistakes and those of others. In the ninth inning of a game against the St. Louis Browns, Piersall imitated legendary pitcher Satchel Paige’s every move, finally resorting to flapping his arms like a chicken and squealing like a pig. (The Red Sox rallied for six runs, including a walk-off grand slam by Sammy White, to beat the rattled Paige.)

Perhaps most outrageously, when returning to the dugout from right field he ran directly behind center fielder Dom DiMaggio, imitating the gait and mannerisms of his teammate, who was revered by Red Sox fans. Not surprisingly, his fellow players thought he was “bush” and did not want to play with him. Boudreau benched Piersall again on June 15, claiming, incorrectly, that he wasn’t hitting. Such a move was not without its own risk, since an earlier benching had caused Piersall to break down in tears.

On June 28, Piersall was demoted to Birmingham. At first glance it was a shocking move, as Piersall was a fan favorite and playing well. Cronin defended the move to the press. “I’ve never seen Lou so nervous,” said Cronin. “After he sat shaking in my office for some time, he finally told me Piersall had to go for the good of the club. Lou said, time and again he had begged Piersall to behave himself but that he just got worse and worse every day.”3 Cronin told another writer, “Apparently everyone on this club is against him.”4

In Birmingham, Piersall’s behavior grew worse. Among his antics, he stole the game ball from the pitcher’s mound on his way to his position and refused to give it up, joined his manager in an argument with an umpire only to mimic his skipper’s mannerisms, and dropped his bat to mock the pitcher from the batter’s box. During a three-day break for the Southern League All-Star Game, Piersall flew back to Boston to see his family. While home, he went to see Cronin, begging to be brought back to the Red Sox. Cronin told him, “Go back to Birmingham and behave and perhaps something will turn up later.” Piersall went back, but his six ejections and four suspensions indicate he did not follow Cronin’s advice. After one ejection for arguing balls and strikes, he pulled out a water pistol and sprayed home plate. “Now maybe you can see it,” he told the umpire. This action drew Piersall his fourth suspension. He again flew back to Boston.5

Cronin had decided that Piersall should be seen by a psychiatrist, but it took some time to get his player to agree. He spent most of July 18 with Piersall, driving around the city and talking. The next day, Cronin drove Piersall and his wife, Mary, to see a doctor, who described the patient as “very nervous, very tense, a very sick boy.”6 He advised that Piersall check into a private sanitarium for a prolonged rest. “I have this to say and it’s going to be brief,” Cronin told the press before that evening’s game. “After consulting with, and on the advice of, doctors, Piersall is to take a rest. The ballclub is primarily interested in Jim Piersall, not where, how, or what position he is going to play. I think you people will acquiesce in that decision. I’m sorry I can’t elaborate.”7 Piersall checked into Baldpate, a private facility in Georgetown, Massachusetts. After a couple of “escapes” and at least one violent episode, Piersall was moved to a state mental hospital in Danvers, and subsequently to a facility in Westborough, which was closer to his wife and children.

Piersall’s official diagnosis was manic depression, what we today call bipolar disorder. Strapped to a bed, he received shock treatments and drifted in and out of coherence. Electroshock therapy was not uncommon in the 1950s as a way to reduce immediate symptoms (including paranoia and severe mania), but at the risk of memory loss. At the end of his hospital stay, in early September, Piersall could remember very little of what had happened after he had reported to Sarasota in mid-January. He did not remember he had made the Red Sox club, let alone the sequence of events that led to his hospitalization.8 Piersall was prescribed medication to stabilize his mood swings and control his condition, and 50 years later was still taking lithium.9

Cronin visited Piersall several times in the hospital, but did not speak with the press about the situation again until Piersall was released, when Cronin reported that his player was “much improved and may play ball again.”10 Piersall spent a few evenings at Cronin’s house listening to the team when they were on the road. Cronin was shocked to discover that Piersall had no memory of having played for the Red Sox earlier that season.11 The Red Sox rented a five-room house in Sarasota for Piersall and his family to spend the winter. The doctors approved, on the condition that Piersall not pick up a baseball until the start of spring training. Piersall played golf, fished, and relaxed by the pool for four months.12

Piersall has blamed his 1952 breakdown at least partially on Boudreau’s moving him to shortstop. In 2008, Piersall told a reporter, “Boudreau was a jerk. I was an all-star center fielder, but he wanted to make a shortstop out of me.”13 On the other hand, many observers thought he was doing a fine job at short when a batting slump caused him to lose his job in early May 1952. His worst behavior actually began when he started playing the outfield in June. Boudreau’s move was bold and evidently wrong, but many men have been asked to switch positions early in their career without experiencing a nervous breakdown. Furthermore, Piersall’s illness was genetic, and not caused by any outside event. His breakdown did not have to happen in 1952, but it almost certainly would have happened sometime.

In March 1953, Piersall arrived at spring camp, in an attempt restart his baseball career. According to his first autobiography, Piersall was treated splendidly by his teammates, opponents, umpires, and fans. He joked with Mickey McDermott and Billy Martin, his combatants in 1952. He won the right-field job, and quickly lived up to all the reviews from the previous spring, making a series of game-saving catches. On May 9 he made a catch in Boston in deep right field that Phil Rizzuto called “the greatest catch I’ve ever seen.” A New York writer called him “the greatest outfielder who ever lived.”14 To Casey Stengel, Piersall was the “best defensive right fielder” in history. He played in 151 games, batting .272 with three home runs while leading the league with 19 sacrifice hits, mainly hitting second in the batting order after Billy Goodman. On June 10 he went 6-for-6 against the Browns, the first Red Sox player ever to accomplish this. The Associated Press named him Sophomore of the Year and he finished ninth in the league’s MVP voting.

After the season the Red Sox acquired slugging outfielder Jackie Jensen from the Senators. Because of Piersall’s great right-field play in 1953, early the next year Boudreau played Jensen in center and Piersall in right for home games, then flipped them on the road. To protect Piersall’s reckless play, the club padded the bullpen fences with foam rubber for the first time. After several weeks of changing positions, Piersall stayed in right for the rest of the season. In 1954, Piersall raised his average to .285 and clubbed eight home runs. On May 14 he was ejected and later fined for arguing a third-strike call from umpire Frank Umont, his first ejection since 1952. On August 16 the Red Sox played an exhibition against the Giants at Fenway Park, before which Piersall and Willie Mays took part in a throwing contest. Piersall hurt his arm and missed several games. He later claimed that his arm never recovered from this accident.

Piersall’s success was at least partially due to his study of the game. He kept his own notebook filled not just with notes about pitchers, but also about opposing batters—he would position himself defensively, and also told Jensen where to play.15 Ted Williams told writers that Piersall was constantly asking him about pitchers. He made his first All-Star team in 1954, playing right field for the final half-inning of the American League’s 11-9 victory in Cleveland.

With the help of sportswriter Al Hirshberg, in 1955 Piersall’s autobiography, Fear Strikes Out, first excerpted in the Saturday Evening Post, was published in the spring. It was a startlingly honest book, for which Piersall received much sympathy and praise. “I was aware that many others had been afflicted like I was,” he said at the time, “or were even now experiencing the same mental sickness and I felt if they learned how I had conquered mine, they would become enheartened in their own efforts at rehabilitation.” Piersall received thousands of letters, many from patients or their parents. The book went through many printings and was twice made into a movie—in 1955, a television version starting Tab Hunter, and in 1957 a cinematic release starring Anthony Perkins. (People considered for the role included James Dean, who died before the role was cast, and Piersall himself.)

In 1955, Piersall finally shifted to center field full time, a position he played the next several years. He started terribly at bat, hitting just .211 at the end of May, before four very good months brought him to .283 at season’s end. He hit 13 home runs and 25 doubles, and drew 67 walks. The next year, Piersall increased his productivity again, hitting .293 with 14 home runs, a league-leading 40 doubles, and 87 runs batted in. He made his second All-Star team, playing two innings and grounding out in the ninth inning of the American League’s 7-3 loss in Washington.

After a game in Chicago in July, Piersall’s work ethic was praised by none other than Rogers Hornsby. “Piersall in my opinion is a throwback to the old time ballplayer,” said Hornsby. He praised Piersall’s batting practice ritual of playing various depths and positions in center field in order to get used to different angles and approaches to the ball. “How many around today are ambitious enough, or smart enough, to work that hard at their jobs? If there are any around, I haven’t seen them.”16 Casey Stengel, a longtime fan of the center fielder, heaped on more praise in August. “When one of our men hits the ball to center field, Piersall is off before you can turn your head to look at him. I’ve never seen anybody as quick as he is.” After the 1956 season the Boston writers voted Piersall the Red Sox’ Most Valuable Player.

By 1957, Piersall was making $22,500 from the Red Sox, held down well-paying jobs in the offseason, and was in demand as a speaker due to his talent and dramatic story. That year Piersall’s average dropped to .261, but he hit 19 home runs and scored 103 runs, both career highs. He received an honor of another sort that year when Gussie Moran, a tennis player of the time known for her provocative outfits, named Piersall one of the 10 most handsome men in baseball for a Sport magazine story. “If I were an artist with a brush, this is the man I’d like to paint,” wrote Moran of the center fielder.17

In 1958 Piersall suffered through his worst season, hitting just .237 with eight home runs, as he battled a rib cage injury suffered when Tigers infielder Billy Martin landed on Piersall after a slide at second base. He did win a Gold Glove award, in only the second year they had been awarded. After the season, the Red Sox traded Piersall to the Indians for Vic Wertz and Gary Geiger. Piersall was stunned by the deal. He had just started a business in Boston and bought a new house, and claimed that general manager Joe Cronin had assured him that his job was safe. What’s more, the ever-growing Piersall clan now featured six children ranging from one year old to seven, with another on the way.

Piersall did not have a good first year in Cleveland, batting just .246 in 100 games, just 77 as a starter. He lost his job to Tito Francona, who hit .363 with 20 home runs in what would be the best season of his career. After the season, the Indians traded Minnie Minoso and moved Francona to left field, and center fielder Piersall responded with a fine season–.282 with 18 home runs. The season was not without its drama, however.

Although Piersall had mainly behaved himself during the six years in Boston after his recovery, he never stopped his on-field clowning—with fans, fellow players, and umpires—and he continued his bench jockeying and umpire skirmishing. He was an entertainer. His antics began to draw attention during his years in Cleveland. He was ejected from three games in 1959, once for charging pitcher Pedro Ramos with his bat on May 3. On May 30, 1960, in Chicago he was on second base when he began arguing balls and strikes with the home-plate umpire, causing second-base umpire Cal Drummond to eject him. After a violent chest-on-chest argument, Piersall retreated to the dugout and threw all of the bats, balls, gloves, and hats he could find out of the dugout. This tirade cost him $250. In the second game of that day’s doubleheader he caught the game’s final out in center field, and then threw the ball into the White Sox’ famous electronic scoreboard, shattering several bulbs.

On June 19, he argued balls and strikes with umpire John Stevens; after stroking a single to center, he continued yelling at Stevens while running to first base, leading to another ejection.

On June 24 he was watching pitcher Jim Coates warm up before the start of the game; when Coates threw a ball in his direction, Piersall responded by throwing two bats at the pitcher. In the ballgame, while playing center field, he showed his displeasure at a ball called to Mickey Mantle by flinging his glove high in the air. In the same game he made obscene gestures at an official scorer who ruled that Piersall’s bunt attempt was an error and not a single. Two days later he argued with umpire Hank Soar when he was thrown out at second base; when the yelling carried over into the next inning, Soar finally ran him. After this game, the Indians sent Piersall home, and requested that he receive psychiatric care. Piersall denied he needed help, but did see a doctor and sent a telegram to his teammates apologizing for any embarrassment he may have caused them. He returned on July 4, having missed six games.

On July 23 in Boston, Piersall was ejected for going into a “war dance” in center field to try to distract Ted Williams at bat, drawing another $100 fine. After more umpire baiting at Fenway Park on the 25th, league president Cronin summoned Piersall and his wife, Mary, to his Boston office on July 26 for a “fatherly talk,” an event that recalled a meeting the couple had with Cronin during Piersall’s difficulties in 1952. This time, Piersall pledged to give up his antics and concentrate on baseball. In the meantime, the Indians players had scheduled their own meeting to discuss Piersall’s behavior, but canceled it when Piersall gave them the same pledge.18 His ejection in Boston was his sixth of the season, but he was thumbed just one more time that year. Still, Piersall’s seven ejections remain the highest total for a player in major-league history, matched only by the Braves’ Johnny Evers in 1914.19 One more humorous incident from 1960: On July 28 in New York, he hid behind the center-field monuments during a pitching change, and had to be coaxed out to get the game to resume.

Piersall’s off-field fame continued, making him sought after for public appearances, and he had a well-paying off-field job as a spokesman for Neptune Sardines. He played one more year in Cleveland, 1961, when he hit a career high .322 in 121 games, and won his second Gold Glove award. He had another celebrated on-field incident, though not of his doing. In a game in Yankee Stadium, two men came out of the center-field bleachers after Piersall, yelling, “You crazy bastard, we’re going to get you.” Piersall dropped the first with a punch to the face, and then chased the other, barely missing him with a kick to the rear. Both men were arrested, and Piersall received nothing but sympathy for the incident.

After the season, the Indians traded Piersall to the Washington Senators for three players. Piersall loved his years in Cleveland, but was unhappy with the Senators. He hit just .244 in 135 games in 1962, and was at .245 the next year when he was dealt to the Mets in exchange for Gil Hodges, who was named the Senators’ manager. Piersall spent just 40 games with the Mets, hitting .194 with one home run, but the home run was perhaps the most memorable he ever hit. It was his 100th home run, hit June 23 in the Polo Grounds off the Phillies’ Dallas Green, and he celebrated the hit by running backwards (but in the proper order) around the bases. The picture put Piersall in headlines once again. On July 27 he was released, and was picked up by the Los Angeles Angels.

Piersall spent five partial seasons with the Angels. He finished the 1963 season with them, hitting .308 in 20 games before injuring a hamstring and missing the final month. The next season, he played 87 games as the club’s fourth outfielder, posting a fine .314 batting average. He played two more full seasons as a reserve, hitting .268 and .211, before closing out his career with four hitless plate appearances in 1967. He loved his time with the Angels and manager Bill Rigney, but retired in early May when he realized he could no longer hit.

Piersall enjoyed his four years in California off the field. He took acting classes, which got him many roles in commercials and television shows. He appeared, mainly as himself, opposite Lucille Ball, Milton Berle, and Don Rickles on their programs. He hosted The Jimmy Piersall Show on radio station KABC six nights a week during the offseason. All of this fame garnered him many appearances at banquets and clubs during his days there.

Piersall’s life after his baseball career was nomadic. He spent two years as the general manager of the Roanoke Buckskins, a minor-league football team in Virginia. He managed a hotel for a while. In 1972 he handled group sales for the Oakland Athletics, which led to many unhappy days being screamed at by A’s owner Charlie Finley. After one year, Piersall quit, and spent several weeks after the season in a Roanoke hospital being treated for nervous exhaustion. Next came a year managing the Orangeburg Cardinals in the Western Carolinas League, and two years coaching and selling tickets for the Texas Rangers.

Piersall’s personal life was equally news-filled in these years. He and his wife, Mary, had nine children, but divorced in early 1968 and Piersall rarely lived near his children again. He married again, to a woman in Roanoke, but they were divorced during his years with the Rangers. He had a few health problems, culminating in heart surgery in January 1976.

In 1977, Piersall began a long career as a broadcaster for the Chicago White Sox, working beside Harry Caray. Theirs was a very productive and popular pairing, but Piersall continually got in hot water with the team for his criticisms of the White Sox players and for his off-color commentary. When told that Mary Frances Veeck, the wife of White Sox owner Bill Veeck, disliked some of his comments, Piersall said, “Mrs. Veeck is a colossal bore. She ought to stay in the kitchen where she belongs.” In response, the Chicago Sun-Times ran a poll asking if Piersall should be fired. Instead he received overwhelming support and kept his job. Bill Veeck himself, aware of Piersall’s popularity, kept silent.

Piersall also worked as a part-time outfield coach with the White Sox, but manager Tony La Russa and the players forced his dismissal during the 1980 season because of the way he was describing their play during games. Soon thereafter, Piersall attacked a local writer, Bob Gallas, grabbing him around the throat, apparently because the writer was interviewing players about Piersall. Mike Veeck, the son of the owner, later looked for Piersall in the broadcast booth, and the two had their own scuffle. Bill Veeck forced Piersall to visit a psychiatrist, but when he got a clean bill of health, he again held on to his job. A couple of years later, on Mike Royko’s radio show, he referred to the players’ wives as “horny broads” who wanted security and money from their “big, strong ballplayer.” He worked the games through 1982 before his constant bashing of the team caused new owners Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn to let him go.

Piersall married his third wife, Jan, in 1982. In 1985 he began a long run with a drive-time talk show in Chicago, which he supplemented with a job as an outfield instructor for the Cubs. In 2000, he told an interviewer that he was a millionaire, a testament to clean living (ne never smoked, drank, or socialized much) and frugality. Piersall loved baseball, loved to fish, and loved to talk. Into his 80s, living in Chicago with Jan, he was still doing the occasional radio show and making public appearances.

He died at the age of 87 on June 3, 2017.

If Piersall is most remembered for his nervous breakdown, it is most unfortunate. His two All-Star games, two Gold Gloves (though the award did not start until after his best defensive seasons), and long career speak briefly to his on-field achievements; his memorable antics speak to his value as an entertainer. He has often said that his breakdown was the best thing that ever happened to him—it made him famous. But it also led to his treatment, and six more decades of a remarkable life.

Sources

For this story I relied heavily on Piersall’s two autobiographies: Fear Strikes Out with Al Hirshberg (Atlantic, Little, Brown, 1955) and The Truth Hurts with Richard Wittingham (Contemporary, 1985). In addition, I utilized an extensive collection of newspapers and magazines from throughout his career, some from his Hall of Fame clipping file and others from ProQuest Historical Newspapers online. The important citations are in the end notes.

Notes

1 Harold Kaese, “Boston’s Shortstop Gamble,” Sport, August, 1952, 20.

2 Ibid.

3 Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1952, B1.

4 The Sporting News, July 9, 1952.

5 The Sporting News, June 25, 1952; July 2, 1952.

6 The Sporting News, July 16, 1952.

7 The Sporting News, July 30. 1952

8 Jim Piersall and Al Hirshberg, Fear Strikes Out (Boston: Little Brown, 1955); The Sporting News, June 25, 1952; July 2, 1952.

9 Bob Kohler, “Striking Fear On the Court,” Boston Globe, October 5, 2006.

10 Los Angeles Times, September 12, 1952.

11 Will McDonough, “A man for one season every day of his life,” Boston Globe, unknown date shortly after Cronin’s death on September 7. 1984.

12 Jim Piersall and Al Hirshberg, op. cit.

13 Doug Segrest, Birmingham News, May 28, 2008.

14 The Sporting News, May 28, 1953.

15 New York Times, August 3, 1954.

16 Christian Science Monitor, July 30, 1956.

17 Gussie Moran. Sport, September 1957.

18 The Sporting News, August 3, 1960.

19 SABR’s ejection database, compiled by Doug Pappas. Courtesy David Vincent.