Dennis Eckersley – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Cleveland pitcher Dennis Eckersley was pitching pretty well. His last outing was a 12-inning game against Seattle, in which he held the Mariners without a hit from the sixth inning on, covering the last 7 2/3 innings. He was rewarded with a complete-game win, when the Tribe pushed a run across in the last of the 12th inning to give Cleveland a 2-1 victory.

Cleveland pitcher Dennis Eckersley was pitching pretty well. His last outing was a 12-inning game against Seattle, in which he held the Mariners without a hit from the sixth inning on, covering the last 7 2/3 innings. He was rewarded with a complete-game win, when the Tribe pushed a run across in the last of the 12th inning to give Cleveland a 2-1 victory.

His next assignment was a tough one, to be sure, a Memorial Day matchup against the California Angels and their ace, Frank Tanana. As in the previous game against the Mariners, the Cleveland lineup had a difficult time putting together an offensive attack. Duane Kuiper’s one-out triple to center field in the first inning led to the Indians’ lone tally, when he scored on a suicide squeeze by Jim Norris.

But the 22-year-old Eckersley was spectacular on the warm late spring evening of May 30, 1977. After surrendering a walk to Angels first baseman Tony Solaita in the top of the first inning, Eck mowed down the Angel hitters. Pressure mounted as the game progressed, inning by inning; it was three up and three down for the Halos. In the eighth inning, outfielder Bobby Bonds advanced to first base on a swinging third-strike wild pitch. But he was erased at second base on a questionable call when the next batter, Don Baylor, bounced into a 6-4-3 double play.

In the bottom of the frame, Ray Fosse flew out to left field for the third out. As Angels outfielder Joe Rudi jogged back to the dugout, he planted a light kiss on the baseball and tossed it to Eckersley as he approached the mound. “Joe kissed the ball, smiled and tossed it out to me. I think he was wishing me good luck or something. It was nice of him. It showed he’s got real class,” explained Eck.1

The sparse holiday crowd of 13,400 was up on their feet for the top of the ninth inning. After retiring the first two batters, only Gil Flores remained between Eckersley and the no-hit game. Flores was not too anxious to step into the box. “I yelled at him to stop messing with me and step in,” said Eck. “I threw him all sliders and got him.”2 Eckersley later told the Contra Costa Times. “I pointed at him, ‘Get in there. They’re not here to take your picture. You’re the last out. Get in there.’ I was pretty cocky back then.”3

Flores was the 12th strikeout on the evening for Eckersley. Angels starter Frank Tanana pitched well, too, scattering five hits and surrendering just the one run, in the first inning of the 1-0 loss. California manager Norm Sherry was complimentary of Eckersley’s near-perfect performance. “A super ballgame right down the drain,” lamented Sherry. “But Eckersley was simply outstanding. He threw hard and he threw strikes. We didn’t make a well hit out all night.”4 Rudi agreed with Sherry. “Eckersley had a great fastball, great curveball, great everything,” he said.5

Reporters informed Eckersley that the record for consecutive hitless innings was 23, held by Cy Young in 1904. The mark gave the 22-year old right-hander a record to shoot for. His next start was against the Mariners at the Kingdome on June 3. He went the first 5 2/3 innings before giving up a home run to Rupert Jones, the only hit the Mariners managed in a 7-1 defeat. His total was 22 1/3 innings of pitching hitless ball, falling two outs shy of Young’s record.

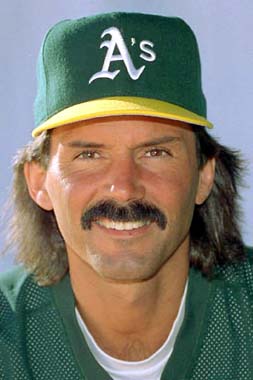

Dennis Lee Eckersley was born October 3, 1954, in Oakland, California, the middle child born to Wallace and Bernice Eckersley (he had an older brother Wally and a younger sister, Cindy). Wallace Eckersley worked as a warehouse supervisor, and Bernice worked as a keypunch operator. Eckersley was a standout athlete at Washington High School in Fremont, California. Cleveland selected him in the third round, (#50 pick overall) of the June amateur draft in 1972.

Three days after graduating from high school, the 17-year-old Eckersley embarked on his professional baseball career, reporting to Reno of the Class A California League. He stayed there for two years, honing his skill. Before the 1973 season, he married his high school sweetheart, the former Denise Jacinto. They had one daughter, Mandee.

The next season, he started off on fire at AA San Antonio of the Texas League. He won his first eight decisions for the Brewers, including a seven inning one-hitter against Shreveport. He ended the season posting a 14-3 mark with a 3.40 ERA.

His effort propelled him right past Triple A ball, and to the Indians in 1975. New manager Frank Robinson liked what he saw of Eck in spring training, and convinced General Manager Phil Seghi to keep him on the varsity. “Every time I used him in spring training, he got people out. I mean, every time,” recalled Robby. “He didn’t have one bad game. They (the front office) worried about his confidence if he got hit a couple of times in the majors, but Dennis had tremendous confidence. Finally I said, ‘Look, let me keep him. I’ll work him out of the bullpen, break him in gradually and keep the pressure off.’ That is the only reason Dennis opened that season as a reliever. I wanted to start him, but the front office wouldn’t let me. I figured that having Dennis in the bullpen was better than not having Dennis at all.”6

Eventually, Robinson got his way. Eckersley made his first start at home against the three-time World Champion Oakland Athletics on May 25, 1975. It was a baptism by fire of sorts, and Eckersley proved that his promotion to the rotation would be heavenly. He blanked the A’s on three hits, striking out six in the 6-0 win. “I was giving them my fastball until I began to feel a little dizzy from the heat,” said Eck. “My stomach cramped up, too. Then I went to my sinker. It sank more, the more tired I got. So I stayed with it the rest of the way.”7

To prove it was no fluke, Eckersley won his next start in Oakland on May 31. Pitching before family and friends, Eckersley scattered six hits and struck out five in the 4-1 victory. “I got by because I throw strikes and made ‘em keep the ball in play, and everybody behind me caught it or picked it up,” said Eckersley.8

He finished the year with a 13-7 record and a 2.60 ERA. He led Cleveland’s starters in ERA and the entire staff in strikeouts (152). He was named American League Rookie Pitcher of the Year by The Sporting News.

Over the next two seasons, Eckersley pitched just a tad over .500. He posted career-high numbers in strikeouts (200 in 1976 and 191 in 1977) and was named to his first All-Star Game in 1977 at Yankee Stadium. He pitched two innings of no-hit ball for the American League. However, the Indians offense did not give Eckersley much run support. Only one player hit over 20 homers, and only one player hit over .300 in each year. No batter surpassed 83 RBIs in either season.

Although it appeared Eckersley, at 23, would be a star pitcher, rumors persisted that the Indians were trying to move him. The front office noted that Eckersley gave up the long ball much too often, had trouble against left-handed batters, and that base runners ran too easily on him. They were also concerned about his delivery from the mound. He used a high leg kick, to emulate his boyhood idol Juan Marichal. He followed it with a side-winding delivery that the Tribe brass worried could eventually cause him arm problems. Boston was seeking a number one starter to their staff, believing that was the final piece of the puzzle to overtake New York in the East Division. So on March 30, 1978, Cleveland sent Eckersley and catcher Fred Kendall to the Red Sox for pitchers Rick Wise and Mike Paxton, infielder Ted Cox, and catcher Bo Diaz.

“Eckersley can do for us what Tom Seaver does for Cincinnati,” said Bosox manager Don Zimmer. “He’s that good. He’s one of the five best pitchers in the league. Last year we finished 2 ½ games behind the Yankees because of pitching; our top winner had 13 victories and he was a reliever (Bill Campbell). Give us a 17-game winner and we win it.”9

Eckersley went from a perennial second division club to a contender. He lived up to his “Number 1 Starter” billing by posting a 20-8 record with a 2.99 ERA. Nine of his victories came after a Red Sox loss, each time giving Boston a victory when they needed it. He was the consistent starter Zimmer had craved. He also adapted quite well to Fenway Park, posting a record of 11-1 at home. “Eckersley has adapted himself to Fenway very well,” said the New York Yankees’ Graig Nettles. “Instead of letting his fastball get up, he is keeping his sliders down low. If he continues to do that, he’s going to be awfully tough to beat.” 10

For the Red Sox, it was a streaky year. They held a seven-game lead over New York on August 30, then went on a 3-14 skid to trail the Yankees by 3 ½ games. Boston put together a hot streak of 12-2, winning their last eight in a row to catch the Yankees on the final day of the schedule and force a single-game playoff, won by New York. In the hot streak down the stretch, Eck won four straight games.

Eckersley continued to pitch well the next season, posting 17 wins. From July 11 to August 14, he won eight straight games, with the first seven of those being complete game victories. He developed a sore arm and won only one game the rest of the year. “I was just tired from all the pitching [246 2/3 innings],” said Eck. “It usually happens to me every year, although only once before did it really hurt. That was either my first or second year when I was in Cleveland, but the arm bounced back after the long winter rest.”11

Eckersley had gotten divorced shortly after he came to Boston. In the offseason, he married the former Nancy O’Neil. They had one son, Jake, and a daughter, Allie.

But the soreness never did subside and Eckersley also developed back and shoulder injuries over the next few years in Boston. He still pitched well on occasion, as shown by a one-hitter he threw at Toronto on September 26, 1980. He struck out nine Blue Jays, giving up a solo home run to John Mayberry for their only hit in the 3-1 win. But home runs continued to plague him. Not counting the strike-shortened season of 1981, Eckersley surrendered 142 round-trippers in five full seasons with Boston.

The Chicago Cubs found themselves in the unlikeliest position of first place early in the 1984 season. They had a strong offensive club, but injuries to Dick Ruthven and Scott Sanderson depleted their mound corps. General Manager Dallas Green went looking for help, and on May 25, he dealt first baseman Bill Buckner to Boston for Eckersley and infielder Mike Brumley. Three weeks later he acquired Rick Sutcliffe from Cleveland, and together, Eckersley and Sutcliffe won 26 games for the Cubs, bringing stability to the pitching staff. “His attitude and personality are just special,” Cubs reliever Dickie Noles said of Eck. “He’s a unique person. He’s got his own lingo for balls and strikes and hits. ‘Throw some gas.’ That man ain’t taking me bye-bye’. He would say ‘I got the slide Johnson going and threw some gas.’ One thing about Dennis Eckersley, I never saw anyone work as hard as this guy and it shows.” 12

The Cubs won the National League’s Eastern Division, returning to the postseason for the first time since 1945. They looked poised to have their ticket punched to the World Series as well, having won the first two games of the NLCS at Wrigley Field. Eckersley toed the rubber for the Cubs in Game Three, but the Padres chased him in the sixth inning. Eck gave up five runs and did not strike out a batter in the loss. San Diego won the next two games, eliminating the Cubs.

In 1986, Eckersley developed tendinitis in his shoulder, which led to a miserable year. He posted a 6-11 record, with a 4.57 ERA, the fourth-highest among NL starters. He led the league in doubles, giving up 58 two-baggers.

Nancy Eckersley began to notice that Dennis had started drinking, a problem that he had off and on during his career to this point. “The first year in Chicago wasn’t too bad,” said Nancy. “But then Dennis started drinking again. I could see it in his eyes; hear it in his voice on the phone.”13 The disease took hold of him at an early age. As a teenager, he hung around a lot with his older brother Wally, who carried a big influence over his younger sibling. “We were out to get drunk, not to have a couple of beers,” said Dennis.14

His miserable season in 1986, combined with day games in Chicago, was a recipe for Eck to fall back to his old ways. Nancy attended Al-Anon meetings because of Dennis’ drinking. He hit rock bottom, when over the holidays, he watched a videotape of how he was acting when he was on a binge. He was horrified by the sight, and also that it was in front of his daughter, Mandee. Although the videotape was shocking, it told a truth that Eckersley may not have been ready to admit or face: He was an alcoholic. He subsequently checked himself into a rehab facility, and has been sober ever since.

As he tried to put his personal life together, his professional life took another turn when Chicago dealt Dennis to Oakland before the start of the 1987 season on April 3. He was returning home, although he was unsure of what his role on the A’s would be. Manager Tony La Russa dispatched Eck to the bullpen. When stopper Jay Howell developed arm problems, Eck was given the closer role. Howell and Eckersley shared the team lead in saves with 16 apiece, but it was Howell who was traded after the season as part of a three-team deal that brought Bob Welch from the Dodgers.

The Athletics were putting together a juggernaut in the American League. They had offensive firepower with Jose Canseco, Mark McGwire, and Dave Henderson. They had speed with Rickey Henderson, and with the acquisition of Welch, another starter to go with Dave Stewart and Mike Moore. But the one constant to the team was Dennis Eckersley in the back end of the bullpen. La Russa used Eckersley as his stopper, inventing the one-inning closer. In keeping his work down to one inning, his arm problems were a distant memory. “A year earlier, I don’t think it would have worked,” said Eckersley. “I couldn’t have been an every-day pitcher when I was drinking. But at Oakland I changed jobs at precisely the right time, and I give the A’s credit for that. They took the gamble by trading Howell last winter.”15

La Russa credits Oakland pitching coach Dave Duncan with coming up with the idea of first using Eck being a reliever, then a stopper. Duncan explained Eckersley’s transformation this way: “Eck always throws strikes, and he has the heart of a giant. His natural response is to challenge a crisis head-on. That’s what makes him such a great reliever. And it’s not tough on his arm if he’s used right. Think of it this way: Aren’t you less likely to break down running two miles every day than 10 miles every fifth day?”16

In 1988 Eck led the majors in saves with 45, as the Athletics captured the first of three straight pennants. Eck was named Most Valuable Player of the ALCS, when he saved all four Oakland victories as the Athletics swept Boston. But every closer has a bad day, and unfortunately for Eckersley, his came on baseball’s biggest stage. In Game One of the World Series, Eckersley was brought in to face the Dodgers in the bottom of the ninth inning, trying to preserve a 4-3 lead for the starter, Dave Stewart. He retired the first two batters with little trouble, but then walked pinch-hitter Mike Davis. Up stepped Kirk Gibson, another pinch-hitter who was suffering from a sore leg. Gibson hit the 3-2 backdoor slider from Eckersley over the right-field wall of Dodger Stadium; the Dodgers won the game, and waltzed their way to winning the Series, four games to one. “When he hit it, I just sank,” said Eckersley. “I guess I’m glad it wasn’t a Ralph Branca job that ended the season, but it was bad enough. Usually when you give one up, teammates will pat you on the behind, and say ‘Go get ’em next time.’ We were all so stunned, no one said a thing.” 17

But Eckersley shook it off, and the next two years he was so magnificent, he lowered his ERA by almost one whole run each season, and in 1990 it was a miniscule 0.61 in 63 appearances, all in relief. From 1989 to 1991, he surrendered just 16 walks. The Athletics were at opposite ends of sweeps in the Fall Classic, sweeping the Giants in 1989, but then falling to the Reds in 1990.

The 1992 season may have been his best yet when he again led the league in saves with 51 with an ERA of 1.91. Opponents hit a meager .158 against Eck with runners in scoring position. He swept all of the postseason awards. The Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA) awarded Eckersley the Cy Young Award and Most Valuable Player. The Sporting News named him AL Pitcher of the Year and AL Fireman of the Year. He was also the recipient of the Rolaids Relief Man of the Year. Milwaukee Brewers pitcher Jesse Orosco, a fine reliever in his own right, was amazed by Eckersley. “Eck’s numbers are unbelievable. I don’t know how, but he doesn’t walk anybody. And a great reliever will have a few blown saves. The man doesn’t even have that.”18

La Russa left Oakland after the 1995 season to take over as manager in St. Louis. Eckersley soon followed when Oakland traded him to the Cardinals for pitcher Steve Montgomery on February 13, 1996. Over two years in St. Louis, Eck saved 66 games. He also saved all three games in the NLDS against San Diego in 1996.

Eckersley finished his career in 1998, pitching one season for the Red Sox. His 390 career saves rank him sixth on the all-time list. His 1,071 games pitched was a record, until eclipsed by Orosco a year later.

Dennis Eckersley was inducted into the Hall of Fame at Cooperstown on July 25, 2004. Like many players in their induction speeches, he offered thanks to a great many people who supported him during his climb to a great major-league career. But he took special note of La Russa and Duncan saying: “I’m being inducted into the Hall of Fame in large part because of Tony La Russa and Dave Duncan. Not only did they change how late innings of a baseball game would be played, they carved out a role that was tailor-made for my personality, aggressiveness, competitiveness and intensity. They created a platform to me to pitch another 12 years. And it is in those 12 years that were my ticket to Cooperstown”19.

In retirement, Eckersley did not move far from the game that he loved. He was a studio analyst for NESN, offering postgame comments on the Red Sox. He was nicknamed “Honest Eck” for his blunt observations. He has also worked as a studio analyst for TBS, working mostly in the postseason. On August 13, 2005, the Oakland Athletics retired his number 43. Washington High School renamed their baseball field in his honor in 2007.

He resides in Ipswich, Massachusetts.

Last revised: May 10, 2021 (zp)

Notes

1 Russell Schneider,”’E’ Is For Eckersley and Easy No-Hit Effort” The Sporting News, June 18, 1977, 5.

2 Bob Sudyk, ”Talent and Luck Equal No-Hitter”, Cleveland Press, May 31, 1977, D3.

4 Marc Lombardo, “Angels Sing Eck’s Praise”, Cleveland Press, May 31, 1977, D2.

5 Ibid.

6 Terry Pluto, The Curse of Rocky Colavito (NY: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 159-160.

7 Bob Sudyk, “Eckersley’s Three-Hitter Saves the Day for the Tribe”, Cleveland Press, May 26, 1975, D3

8 Russell Schneider, ”Eckersley, HR’s stop A’s streak”, Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 1, 1975, Section 3, p. 4.

9 Peter Gammons, “Sox Got ‘No.1’, But Gambled”, Boston Globe (March 31, 1978)

10 Larry Keith, “Suddenly They’re Up in Arms in Boston”, Sports Illustrated, July 3, 1978, 17

11 Joe Giuliotti, “Traveling Man Eckersley Plans To Reduce Routes”, The Sporting News, February 23, 1980, 33.

12 Peter Golenbock, Wrigleyville (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 470-471.

13 Steve Wulf, “The Paintmaster”, Sports Illustrated, August 24, 1992, 62-73.

14Ibid.

15 Peter Gammons, “One Eck of a Guy”, Sports Illustrated,(December 12, 1988)51-59.

16 Ibid

17 Ibid

18 Steve Wulf, “The Paintmaster”, Sports Illustrated, August 24, 1992, 62-73.