Bobby Doerr – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

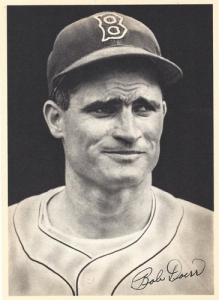

It was Ted Williams who dubbed Bobby Doerr “the silent captain of the Red Sox” and a more down-to-earth Hall of Famer might be hard to find. A career Red Sox player, Doerr’s fame enjoyed a resurgence in 2004 with the publication of David Halberstam’s book about him and his famous teammates.1

It was Ted Williams who dubbed Bobby Doerr “the silent captain of the Red Sox” and a more down-to-earth Hall of Famer might be hard to find. A career Red Sox player, Doerr’s fame enjoyed a resurgence in 2004 with the publication of David Halberstam’s book about him and his famous teammates.1

Born in the city of Los Angeles on April 7, 1918, Robert Pershing Doerr was one of the four Sox from the West Coast who starred in the 1940s — Williams from San Diego, Doerr from Los Angeles, Dom DiMaggio from San Francisco, and Johnny Pesky from Portland, Oregon. Doerr was born to Harold and Frances Doerr. His father worked for the telephone company, rising to become a foreman in the cable department, a position he held through the Depression. The Doerrs had three children — Hal, the eldest by five years, Bobby, and a younger sister Dorothy, who was three years younger than Bobby. Doerr told interviewer Maury Brown, “If she’d have been a boy, she’d have been a professional. She was a good athlete.”2

Baseball came early. “We lived near a playground that had four baseball diamonds on it and when I got to be 11, 12 years old, I was always over at the ballpark practicing or playing or doing something pertaining to baseball. And when I wasn’t doing that, I was bouncing a rubber ball off the steps of my front porch at home.”3 Manchester Playground attracted a number of kids from the area[,] and a surprising number of them went on to play pro ball. Bobby’s American Legion team, the Leonard Wood Post, boasted quite a team. The infield alone boasted George McDonald at first base (11 of his 18 seasons were with the PCL San Diego Padres), Bobby Doerr at second base (14 seasons with the Red Sox), Mickey Owen at shortstop (13 seasons in the major leagues), and Steve Mesner at third (six seasons in the National League.) That was quite a group of 14-year-olds.

Bobby’s older brother Hal played professionally as well, a catcher in the Pacific Coast League from 1932-1936. It was Doerr’s father who helped bring about Owen’s transition from shortstop to catcher in the winter of 1933. The team they put together for some wintertime ball didn’t have a catcher so Harold Doerr urged Owen to give it a try. Mr. Doerr helped out in other ways, too. During these miserable economic times, rather than lay people off, the telephone company reduced many people’s hours to three days a week – which at least provided some income. “It was just Depression days,” Bobby explained. “Sometimes he would buy some baseball shoes for some of the kids, or a glove. Things were tough. Kids couldn’t afford to get it themselves, and he had a job… He tried to help when he could from time to time; some of those kids were even having a hard time having meals at home.”

Wintertime play was important– unlike Legion ball, the games included people of all ages, including some players who had played minor league ball but wanted to pick up a little extra money playing semipro on the playgrounds. “So when I was 15 and 16, I got to play against pretty good professional ballplayers.” That gave Bobby some valuable experience. It also got him noticed.

Doerr told author Cynthia Wilber that his fondest memory as a child was winning the 1932 American Legion state tournament on Catalina Island, winning a regional tournament in Ogden, Utah, then coming within a game in Omaha, Nebraska of playing for the national title in Manchester, New Hampshire.4

Bobby played high school ball for two years at Fremont High, in 1933 and the first part of 1934, but he’d been working out some with the Hollywood Sheiks and they offered to sign both him and George McDonald.5 Both were 16 at the time, and in high school. Bill Lane was the owner of the ballclub and Oscar Vitt was the Sheiks’ manager. Hal was playing for the Portland Beavers at the time. The Sheiks offered an ironclad two-year contract guaranteeing they would not send Bobby out. Bobby’s father let him sign, “but I had to promise that I’d go back to high school in the wintertime and get my high school diploma.” He did. Bobby understands that more professional ballplayers came out of Fremont High than any other high school in the country.

Doerr played 67 games for Hollywood in 1934, batting .259, all but six of the 16-year-old’s 52 hits being singles. In 1935, Bobby acknowledges he “had a pretty good year” – he hit for a .317 average and added some power, hitting 22 doubles, eight triples, and four home runs. He drove in 74 runs, playing a very full 172-game season.

That winter, the Red Sox purchased an option on the contracts of both Doerr and teammate George Myatt, paying a reported $75,000. Bill Lane moved the Hollywood team to San Diego early in 1936, where they were renamed the San Diego Padres. In July, Eddie Collins came to look over the pair while the Padres were playing in Portland, and took Doerr’s contract but declined Myatt. Collins also noticed a young player named Ted Williams and shook hands on the right to purchase Williams at a later time. Doerr improved again in his third year in the Coast League, batting .342 with 37 doubles and 12 triples, though just two home runs. He led the league with 238 hits and scored an even 100 runs.

Doerr was 18 years old when he headed east for his first spring training with the Red Sox, traveling across the country to Sarasota, Florida, with Mel Almada. Doerr made the team in 1937, batting leadoff on Opening Day and going 3-for-5. He had won the starting job and held it until he was beaned by Washington’s Ed Linke on April 26; the ball hit him over the left ear and bounded over to the Red Sox dugout. In Wilber’s book, Doerr says, “It didn’t knock me out, but I was out of the lineup for a few days and Eric McNair got back in. He was playing good ball, so I didn’t play too much that first couple of months. The last month of the season I got back in and I played pretty well for the rest of the year.”6 Eric McNair played most of the games at second but by season’s end, Bobby had accumulated 147 at-bats in 55 games.

Though he batted just .224, he took over second base fulltime beginning in 1938. The right-hand hitting Doerr (5-feet-11, 175 pounds) batted .289 in 1938, with 80 RBIs, playing in 145 games. He led the league in sacrifice hits with 22. Defensively, he helped turn a league-leading 118 double plays. Only once more did he hit less than .270 – he batted .258 in 1947, driving in 95 runs.

Doerr explained to Wilber, “I never did work in the off-season, and I never did play winter ball or anything else. I think it was good for me to get away after a full season….In those days, I don’t think anyone ever got too complacent. Even after I played ten years of ball, I still felt like I had to play well or somebody might take my place. They had plenty of players in the minor leagues who were good enough to come up and take your job, and I think that kept us going all of the time. I hustled and put that extra effort in all of the time.”7

In 1939, he upped his average to .318 and added some power, more than doubling his home run total with 12 roundtrippers. Though his average slipped a bit in 1940 (to .291), he became a more productive hitter, driving in 105 runs, with 37 doubles, 10 triples, and 22 home runs. Again, he led the league in double plays, again turning 118 of them. His 401 putouts also led the AL.

Doerr was named to the first of nine American League All-Star teams in 1941; he played in eight games, starting five of them, and his three-run home run in the bottom of the second inning of the 1943 game, off Mort Cooper, made all the difference in the 5-3 AL win.

Though his RBI total dropped to 93 in 1941, he bumped it back up to 102 the following year, the second of six seasons he drove in more than 100 runs. He led the league in fielding average, too. Come 1943, he played in every Red Sox game all year long (and the All-Star Game), and though his RBI total slipped to 75 – a function of greatly weakened team offense – Doerr excelled on defense, leading the American League in putouts, assists, double plays, and fielding average.

Doerr anchored the second base slot for Boston through the 1951 season, missing just one year (and one crucial month) during World War II. The month was September 1944. When the war broke out, Bobby was exempt because he and his wife Monica had a young son, Don. He’d also been rejected for a perforated eardrum. As the war rolled on, the military needed more and more men and the pressures on seemingly-healthy athletes intensified. After the 1943 season, Doerr took a wintertime defense job in Los Angeles, working at a sheet metal machine shop run by the man who had managed his old American Legion team. When he left the defense job to play the 1944 season, he received his draft orders and was told to report at the beginning of September. By the time September came around, the Red Sox were in the thick of the pennant race, just four games out of first place — and both Doerr (.325 at the time, his .528 slugging average led the league) and Hughson (18-5, 2.26 ERA) had to leave. The team couldn’t sustain those two losses and their hopes sputtered out.

Bobby’s .325 average was second in the league, just two points behind the ultimate batting champion, Lou Boudreau, who hit .327. Doerr was named AL Player of the Year by The Sporting News.

Because of the war, Doerr missed the entire 1945 season. He had made his home in Oregon and so reported for induction in the United States Army in Portland. He was first assigned to Fort Lewis and a week later reported for infantry duty at Camp Roberts. After completing the months of training, word began to circulate within his outfit that they were being prepared to ship out to Ford Ord, and then overseas for the invasion of Japan. President Truman brought the whole thing to a halt by dropping two atomic bombs on Japan.

After the war, Staff Sergeant Doerr changed back into his Red Sox uniform and returned to the 1946 edition of the Red Sox. He drove in 116 runs, his highest total yet – thanks to the potent Boston batting order. Bobby once again led the league in four defensive categories, the same four as in 1943: putouts, assists, double plays, and fielding percentage.

The Red Sox waltzed to the World Series, but lost to the Cardinals in seven games. Doerr led the regulars in hitting, batting .409 with nine hits in 22 Series at-bats. Babe Ruth, asked who was the MVP of the American League, said, “Doerr, and not Ted Williams, is the No. 1 player on the team.”

He averaged over 110 RBIs from 1946 through 1950, with a career-high 120 RBIs in the 1950 campaign. That last full season, he led the league a fourth time in putouts and a fourth time in fielding average. His .993 in 1948 was the Red Sox record for second basemen until Mark Loretta surpassed it with a .994 mark in the 2006 season.

Doerr hit for the cycle twice (May 17, 1944 and May 13, 1947); he is the only Red Sox player to do it more than once. In a June 8, 1950 game, he hit three homers and drove in eight runs. Despite the power demonstrated by his 223 career home runs, his fielding was at least as important. He was always exceptional on defense, more than once running off strings of over 300 chances without an error. He led the league 16 times in one defensive category or another and wound up his career with a lifetime .980 mark – at the time of his retirement, he was the all-time major league leader.

On August 2, 1947, Doerr was given a night at Fenway. He received an estimated $22,500 worth of gifts including a car.

In early August 1951, in the midst of another excellent year, Bobby suffered a serious back problem. He’d hurt it a bit bending over for a slow-hit ground ball; he felt something give, but continued the game. Quite a while afterwards, he woke up one morning and found he could hardly get out of bed or put on his shoes. He got some treatment but missed nearly three weeks before returning to play. He got in only a few more games. The problem persisted, and he had to bow out after just one at-bat in the first game of the September 7 doubleheader. Fears that it was a ruptured disc proved not the case and surgery was ruled out, but Doerr was told to rest the remainder of the season.

At season’s end, Doerr could look back on 1,247 RBIs, a career batting average of .288 and the aforementioned home run and fielding totals, and some 2,042 major-league base hits.

Bobby had played most of his career for just two managers: Joe Cronin and Joe McCarthy. He felt Cronin was “firm, but he patted you on the back; he always encouraged you in different ways. That was when I was younger, and was a big help to me.” McCarthy was a “much firmer disposition kind of guy” who was admittedly “a little more difficult to play for” – but Bobby recognized that he played some of his best seasons for McCarthy.8

He’d played 14 seasons in the majors and had a good career. Though only 33, he didn’t want to risk more serious injury and decided to retire to his farm in Oregon. Over time, the back fused itself in some fashion and he found himself able to lift bales of hay and sacks of grain. He began raising cattle, fattening steers for resale, but there was almost no profit in it for the small herd of 100 or so that he could hold on his spread. When Bobby returned to Boston for a night to honor Joe Cronin in 1956, he was asked if he might like to manage in Boston’s system. He declined, but did take a position that he describes as “kind of like a roving coach in the minor leagues” beginning in 1957. He is listed as a Red Sox scout for the years 1957-66. He did a lot of traveling, checking out Red Sox prospects in Minneapolis, San Francisco, Seattle, Winston-Salem, Corning, and other locations.

Doing this work for several years, Doerr came to know Dick Williams, particularly after Williams took over as manager of the Toronto farm club. “I got to know him pretty good when he was with Toronto. I have to say that seeing him operate in the minor leagues coaching and managing, and then three years at the Red Sox level, he was the best manager that I saw. Now Joe Cronin was very good. I loved Joe Cronin, to play for. But if I had to pick a manager to take a team that was potentially a winning team, Dick Williams someway was able to put something together[,] and I thought he was one of the best managers I saw.”

After he was named Red Sox manager for the 1967 season, Dick Williams asked Bobby to serve as his first base coach. He served for the three seasons that Williams managed, 1967-1969. Doerr agrees that Williams “wasn’t the most liked guy. He didn’t tolerate easy mistakes. Some way or another, though, the players never got uptight playing for him. He kept a tight ship and to take that club in ’67 and put it into a pennant winner, there were so many things he did that he was the best guy I saw.” They did not have frequent coaches meetings. “He said what you’re supposed to do and he let you do it. You worked with the batter. Nobody ever interfered with what I was supposed to do.” Doerr’s job was to work with the hitters, as well as coach first. He was familiar with most of the young hitters, having seen them while doing his work as a roving instructor. Eddie Popowski had the same store of experience, and both offered a stable, almost paternal influence to an exceptionally young ballclub. Dick Williams told interviewer Jeff Angus, “He helped me out quite a bit when I was in Toronto. In ‘67, he was a buffer between people, a soft-spoken guy who could help get the message across.”

Second baseman Mike Andrews of the 1967 Sox told the _Boston Herald’_s Steve Buckley, “Bobby Doerr was my mentor. When I was in the minors, I always seemed to improve when he came along. I had so much faith in him that if he told me I’d be a better hitter if I changed my shoelaces, I’d have done it.”9

After Williams was fired late in 1969, incoming manager Eddie Kasko brought in his new staff for the 1970 campaign.

Several years later, Doerr was named coach for the Toronto Blue Jays, and served them for a number of years as the team’s hitting coach. “I really didn’t want to go back into baseball,” he says, “but they made it so nice for me. Pat Gillick was really good to work with. Peter Bavasi. I was there ’77 through ’81 and then I worked a couple of years in the minor leagues. More or less spring training, up to Medicine Hat with the rookie team. I didn’t do much after ’82, ’83.”

In 1986, Bobby Doerr and Ernie Lombardi were named to the Hall of Fame by the special veterans committee, and were inducted with Willie McCovey in August that year. On May 21, 1988, the Red Sox retired Bobby’s uniform number, #1. Addressing those who might have questioned his Hall of Fame credentials, Bob Ryan of the Boston Globe noted that the nine-time All-Star had a higher RBI-per-game average than players such as Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, and Stan Musial, as well as many others, including Ernie Banks, Orlando Cepeda, Harmon Killebrew, Mike Schmidt, and Willie Stargell.10

Bobby’s son Don Doerr later played some college ball at the University of Washington and went into the Basin League in the middle 1960’s, pitching for the Sturgis club against future major leaguers like Jim Lonborg and Jim Palmer. Bobby rated his curve ball of major-league caliber, but says he “didn’t have quite enough fast ball…didn’t have quite enough to go far in professional ball.”

In his later years, Doerr devoted his life to care for his wife Monica, wheelchair-bound for much of her later years due to multiple sclerosis. Mrs. Doerr suffered two strokes in 1999 and then a final one which brought about her passing in 2003.

Bob Doerr split his time between his two properties in Oregon, and was able to enjoy more time with his son, retired himself after a successful career as a manager with the accounting firm of Coopers and Lybrand, based in Eugene. Bob visited Boston two or three times a year, such as for a reunion of the remaining 1946 Red Sox that kicked off the 2006 baseball season in Opening Day ceremonies. His last visit was in 2012 for the 100th anniversary of the opening of Fenway Park.

Doerr died at the age of 99 on November 13, 2017 in Junction City, Oregon. He had been the oldest living member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame at the time of his death, and the only remaining major-league player from the 1930s.

A version of this biography originally appeared in “The 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox: Pandemonium on the Field” (Rounder Books, 2007), edited by Bill Nowlin and Dan Desrochers.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Thanks to Jeff Angus, Mark Armour, Dick Beverage, Maury Brown, Dan Desrochers, Bobby Doerr, J. Thomas Hetrick, and David Paulson.

Notes

1 David Halberstam, The Teammates (New York: Hyperion, 2004).

2 Maury Brown interview with Bobby Doerr, November 13, 2002.

3 Author interviews with Bobby Doerr, May 8 and 23, 2006. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations come from these two interviews.

4 Cynthia J. Wilber, For the Love of the Game (New York: William Morrow, 1992), 117.

5 The Hollywood ballclub of the period was popularly known as the Sheiks, though one can find references to them as the Hollywood Stars. Dick Beverage, author of The Hollywood Stars, reports of Doerr’s timeframe, “The players I’ve talked to from that era to a man referred to the club as the Sheiks. That was the most popular name. But they were sometimes called the Stars in the papers.”

6 Wilber, 120.

7 Wilber, 118.

8 Doerr’s remarks were made in an interview for the Oregon Stadium Campaign in 2002.

9 Steve Buckley, “The Silent Captain Still,” Boston Herald, May 22, 2005.

10 Bob Ryan, “For Sox, None Better Than Doerr,” Boston Globe, November 15, 2017: C1, 4.