Dámaso Blanco – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

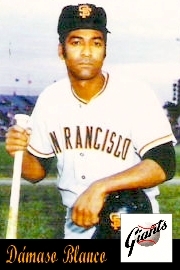

Venezuelan infielder Dámaso Blanco was 30 years old and in his 12th pro season when his dream finally came true with the San Francisco Giants. He told me the story in 2010.

Venezuelan infielder Dámaso Blanco was 30 years old and in his 12th pro season when his dream finally came true with the San Francisco Giants. He told me the story in 2010.

“The most important moment in my baseball career as an active player came on May 26, 1972. That day I played in my first major-league game. I ran for Ed Goodson in the eighth inning as the Braves were beating the Giants 9-2 at Atlanta Stadium. Ron Reed was the pitcher, Earl Williams the catcher. Hank Aaron played first base. When I arrived at the base he told me, ‘Good luck, boy.’ In the bottom of that frame Don Carrithers replaced me, coming in as the Giants pitcher. The Braves ended up winning that game 9-4.

“The day before, Rosy Ryan, the Giants farm director, had called me at the apartment I had inherited from Dave Kingman when he was called to the Big Show. ‘Come to my office, we need to talk to you.’ The first words Rosy told me were, ‘You’ve been plenty of years with us.’ I immediately thought that was it for me. Then he talked about my perseverance and my good behavior. ‘You’ve been a very useful player and finally all your efforts are rewarded. You’ll join the Giants team at Atlanta.’”

Blanco was a familiar type: a fine fielder but light hitter. He appeared in 72 games in the majors, starting just three of them and batting .212 in 39 plate appearances from 1972 through 1974. “I was Willie McCovey’s designated runner,” Blanco said in Pete Rose: My Story. “If Willie got a hit in the late innings, I ran for him.” He left the Giants’ minor league training camp in 1975 and soon began to work as a radio and TV broadcaster of baseball games. For more than 30 years, he has been working as a commentator in the Venezuelan winter league and for Major League Baseball. He is a fine communicator with a great knowledge of the game’s details.

Dámaso Blanco was born in Curiepe in the state of Miranda on December 11, 1941. This town is about two hours east of the nation’s capital, Caracas. Its population is largely of African descent. Founded in the early 1700s by liberated slaves, Curiepe is known for its annual San Juan Festival and its famous drums.

Dámaso was the second of two children born to Candelario Blanco and Bertha Caripe. He and his elder brother Francisco Antonio had to move to Caracas with Bertha when he was one year old after Candelario died. In Caracas Bertha continued their family life with Mr. Cosme Vásquez, a worker for Shell Oil who later retired and worked on his own as a shoemaker. Mr. Cosme became a fine father to the boys. Then came the rest of Dámaso’s siblings: Dilda Esther, Nelda Mireya, Irene Marina, Fernando Gustavo and Marco Antonio.

Dámaso began to play baseball in the streets along with Francisco Antonio and some friends. Bertha didn’t like that her sons played there, and most of the time they played while coming back home after running some errands for her. When Bertha had arguments with the boy for arriving late at home, Dámaso said “I’m going to play professional baseball like Alfonso Carrasquel. I’m going to buy a beautiful house for you. You’ll see.” Alfonso “Chico” Carrasquel – the third Venezuelan to reach the majors – was Dámaso’s idol. That’s why his original position in baseball was shortstop.

Dámaso had to go to work after finishing elementary school because he wanted to help Bertha with the family wages. Baseball always was his passport to find a job. Thus he joined a team affiliated with the government office of Intendencia Naval (Quartermaster’s Corps, in English). With that squad, Blanco won two District Championships and represented Distrito Federal in two national championships of AA baseball, the top amateur level. They won the title in both years, 1959 and 1960.

The 1959 edition – which also featured pitchers Luis Peñalver and Enrique Capecchi, catcher William Troconis, and infielders Rubén Millán and Luis Manuel Hernández – formed the backbone of the Venezuelan team that won the gold medal in the Pan American Games that year. The games took place in Chicago, at Comiskey Park and Wrigley Field. Blanco said in 2010, “I remember that in the medal ceremony, they didn’t have any record with the Venezuelan national anthem. So we the players started to sing the anthem and our emotion flew with our caps at the end of the anthem. It was one of the happiest days in my life.”

Ahead of the 1960-61 season, Blanco signed to play professional baseball in the Venezuelan winter league with the Pampero team. Mr. Cosme signed the contract for Dámaso before the general manager Andrés de Chene, because the youth was still just 18 years old. The same happened when he signed his contract to play in the farm system of the San Francisco Giants with Alex Pómpez and Frank “Chick” Genovese. Mr. Cosme wrote the signature but Dámaso set the terms.

In his first game with the Pampero team, Blanco was very excited because he was playing third base and Alfonso Carrasquel, his hero, was next to him at shortstop. He couldn’t avoid looking at Carrasquel at every chance he had, to see how he positioned himself before each batter. When they returned to the dugout Dámaso tried to sit next to Carrasquel to ask him about his baseball skills.

“I hit my first single in the Venezuelan league against Howie Nunn. It was a soft line drive that landed behind the shortstop. Nunn played in MLB for the Cincinnati Reds. In Venezuela he played for the Valencia Industriales. In that time the players traveled in taxis. The wage was a ham and cheese sandwich the owners gave us before boarding the cab.”

Blanco won the Rookie of the Year award in Venezuela that winter, even though he played in just 28 games while sharing Pampero’s hot corner with Manuel Carrasquel, nephew of Alex and cousin of Alfonso, and Eduardo “Colorao” Monasterios. His batting average was .292.

When he went to his first spring training in the U.S., it was in Texas – and there Blanco first encountered racial discrimination while riding from the camp at Casa Grande to El Paso. When the bus stopped at the hotel, he tried to get off. George Genovese called to him, “No, Dámaso. This is the place where only the white ballplayers will stay. Don’t worry. You should take this as an experience to stress your character.” Before that, in camp he spent a lot of time with Bobby DeJarnette because he played shortstop and DeJarnette second base. The first day they went to eat lunch in the camp, DeJarnette told Blanco, “Excuse me but I’ve never eaten with a colored man.” Dámaso replied, “Don’t worry, in my country we don’t have that kind of trouble.”

Blanco talked about that incident with Alex Pómpez, the minor league coordinator for Latin American players. The Giants organization had a daily meeting each evening during training camp. There Pómpez and Carl Hubbell, the general coordinator of the minor leagues, talked to the players about many different topics: technical, tactical, teamwork, behavior, etc.

Blanco had a good first pro season in Class D with the El Paso Sun Kings. In 130 games, he hit .279 with two home runs, and even though he committed 34 errors at short, he earned good reviews for his fielding. So he was promoted to play with the Springfield Giants in the Eastern League (Class A) in 1962. There he met one of the managers who most influenced his career. Andy Gilbert was a man who showed very little expression and stayed on an even keel. The players could be giving their best performance and Gilbert said only, “Well done, boy” and gave the player a pat on his shoulder. Yet it was the same if the player made an error that decided the game. He left the dugout angry but he didn’t say a word – his face remained the same, win or lose. Gilbert was very important for Blanco’s career and life because he made the young man understand the value of responsibility, discipline and the equilibrium between wins and losses. He learned not to get down so much after a loss and not to be too happy with a win.

Blanco actually spent more of the 1962 season at Class B, but he returned to A ball in 1963, and had by far his most impressive season as a batter. For the Fresno Giants of the California League, under manager Bill Werle, he hit .330 with 5 homers and 52 RBIs in 140 games and was elected to the league’s All-Star team. He had only 13 homers in his entire U.S. pro career – and none in 16 seasons at home in Venezuela. Nonetheless, from 1963 through 1967, Dámaso was a fixture in the lineup of the Caracas Lions, whom he had joined for the 1963-64 season after a trade. This was mainly because of his superb fielding; he was the best defensive third baseman in the Venezuelan league in the 1965-66 season. Caracas also won the league championship in 1966-67.

Blanco spent almost all of the six summer seasons from 1964 through 1969 at the Double-A level. The exception was 15 games at Triple A in 1965, followed by a step back to Single A for 43 games the next year. In the Venezuelan league, he was traded first from Caracas to the Valencia Industriales (in November 1967) and then to Magallanes Navigators ahead of the winter of 1968-69. That season Dámaso learned a lot from manager Napoleon Reyes and from his teammates, including Americans such as Clarence “Cito” Gaston, Pat Kelly, Joe Rudi, Bo Belinsky, and Walt Hriniak. After each game, most of the players – Americans and Venezuelans alike, except for Joe Rudi, who was caring for his infant son – stayed in the dugout. They would order a case of beer to drink while playing dominoes and cards and talking about baseball.

The Navigators won the Venezuelan championship in 1969-70 and went on to capture the Caribbean Series. Blanco said, “What I remember most is that the team moved from Caracas to Valencia. I was one month on the disabled list because I got hit in my left wrist by Larry Staab while batting against him in a contest before the Aragua Tigers. I also remember well pitcher Dick Baney. He won some important games for us, among them a 1-0 victory against Caracas. Donald Eddy came at the end of the season and helped us get a bunch of games to go to the playoffs and in the postseason he continued pitching very well. I also remember Cito Gaston being very sad because he had to leave the team due to an injury in his knee.

“In the last game of the Caribbean Series [against Puerto Rico], I read Sandy Alomar Sr.’s mind and started to run to home plate along with the third base runner, Jorge Roque. I took the bunt with my bare hand and threw it to catcher Ray Fosse who caught it and blocked the runner to make the out and frustrate the squeeze play. I couldn’t believe we had made that out. I shouted in my mind, ‘Very well done. Great play.’”

In 1970 Blanco returned to Triple A with the Phoenix Giants, beginning his relationship with Charlie Fox, who was also his manager for all of the time he was in the majors. The 1970 and ’71 seasons were unremarkable with the bat, with overall total of 1 homer, 86 RBIs, and a .241 average. He was batting .258 after 26 games in 1972 when he got his phone call from Rosy Ryan. Blanco recalled, “I got my first hit in the majors against the Chicago Cubs pitcher Tom Phoebus on June 11, 1972. I came into the game for Chris Speier in the fifth inning because the chief umpire expelled him from the game for complaining about a called strike. I stayed in the game and hit a single to drive in my first run, pitcher Ron Bryant. In the eighth, I hit another single. We defeated the Cubs 3-1 in the second game of a doubleheader at Candlestick Park.

“After the end of that season I got a letter from the Giants where they told me that my contract had been sent back to the minor leagues. I wrote a letter to Horace Stoneham, the owner of the franchise, asking him the reason for the transaction. Later I understood that they were protecting a prospect named Mike Phillips, a very good ballplayer. They could send me to the minors without the risk of losing my contract. A month later the Giants sent another letter inviting me to spring training. I made the team for the 1973 season.

“One of my best memories from my seasons with the Giants is the clubhouse kangaroo court. The atmosphere was one of jokes and relaxation, beginning with the clothes of the judge, who was a player, wearing one of those black and orange team jackets. There they called you to attention – how could you throw right down the middle with two strikes in the count? Why did you arrive at a hotel with a green jacket and orange pants? The fines were symbolic and at the end of the season were used to support the poor children or to throw a party for the players. Once, in the middle of a flight, the court called Horace Stoneham and fined him for keeping Dámaso Blanco in the farm system for more than 12 years.”

“One of my best memories from my seasons with the Giants is the clubhouse kangaroo court. The atmosphere was one of jokes and relaxation, beginning with the clothes of the judge, who was a player, wearing one of those black and orange team jackets. There they called you to attention – how could you throw right down the middle with two strikes in the count? Why did you arrive at a hotel with a green jacket and orange pants? The fines were symbolic and at the end of the season were used to support the poor children or to throw a party for the players. Once, in the middle of a flight, the court called Horace Stoneham and fined him for keeping Dámaso Blanco in the farm system for more than 12 years.”

Blanco was a seldom-used reserve in 1973. “I got a spot with the Giants. Rosy Ryan told me that I made the team but I had to sign a new contract. They were giving me the same contract as the last season, when they promoted me, minimum wage. I told him how was it possible that if that was my second year I wasn’t able to get at least a slight raise in my salary. ‘Well, if you don’t want to sign, don’t do it,’ said Ryan. I replied him that he had to give me an airplane ticket home because that was in my contract. He left with a big slam of the door.

“Ryan went to talk to Charlie Fox and probably related the incident his way. He told me some bad words and I answered him the same way because he had lost my respect. Charlie Fox came to talk to me. ‘I need you on the team,’ he said. ‘Try to avoid having arguments with him [Ryan]. He has a lot of influence in the organization. I think you’re going to help me to win this year. If I didn’t need you, I wouldn’t have picked you to stay on the team. I was the one who brought you to Major League Baseball after you had spent 11 years in the minors. I’m sure we’re going to win the pennant and you’re going to earn more money for that than the difference they could give you for the raise in case they gave it to you. Sign the contract.’

“I couldn’t do anything before Charlie’s reasoning. It was that or go home. I began to think seriously of retirement during that season. I only had 12 at-bats from opening day until July or August. I liked to compete. When you spend so much time on the bench you get rusty. I told myself, ‘Geez, it’s day after day and I don’t play. I’m getting paid for doing nothing. I wasn’t happy with that. I didn’t say anything to the manager because he was the one who carried me to the majors. I needed to work more every day. I took grounders at second base, at shortstop, at third base. I pitched batting practice. I did everything to try to deserve being there.

“At the end of August, when the players from Class AAA are raised, I was demoted to Phoenix. The manager was Rocky Bridges. I joined the team at Albuquerque. I felt depressed because Albuquerque was in the Sophomore League, Class D, when I played my first season. I felt as if I was taking the same route that I did 14 years ago. I haven’t advanced anywhere. I’m in the same place.”

Blanco tried to quit baseball before that series against the Dukes. Rocky Bridges convinced him to stay with the Phoenix team. As Blanco recalled, Bridges said, “I don’t think that’s a smart decision for you. Because while you remain here, you’ll be getting a big-league salary. But if you go home, you don’t get that money. What are you going to do at home the next months? Besides that, we have this series against that blockhead Stan Wasiak.” Wasiak was the manager of Albuquerque, the Dodgers’ top farm team. A great rivalry existed between the two organizations. Bridges told Dámaso that he was very important to win the series. They had a good game in the opener. After the game Bridges said, “You see! You made the difference!”

The 1973-74 Venezuelan winter league season was suspended just after the regular season ended because of a players’ strike. Another sad event took place on took place on January 1, 1974, when reliever Mark Weems, who had already recorded 12 saves for Magallanes, drowned at the Patanemo beach in Carabobo, Venezuela. Fellow Orioles farmhands Bob Bailor and Wayne Garland were among the group that went to the beach to celebrate the New Year. It was similar to what had happened three years before, when Herman Hill drowned at the Guaicamacuto beach on December 14, 1970. The Navigators didn’t play until Weems’ body was recovered, which took a few days. Even afterward, those were very sad times in the dugout, most of all when the ninth inning arrived. All the players looked to the bullpen with glassy eyes.

The 1974 season was Blanco’s last in the U.S.; he played 70 games for Phoenix and got into his last five games in the majors during May and June. Second basemen Tito Fuentes and Mike Phillips were bothered by injuries, and the Giants wanted Blanco for depth. He never got into the field, though, pinch-hitting once and pinch-running four times.

Blanco also played his last full season at home in 1974-75, although he came back for 22 games with the Aragua Tigres in 1976-77, after a year away. His lifetime average at home was .249 in 754 games across 16 seasons.

Blanco also scouted briefly for the Cincinnati Reds before embarking on his broadcasting career. In addition, he wrote a regular column in the newspaper El Nacional from 1973 to 1983. (In 1974, The Sporting News observed that he was starting to prepare for life beyond the field with this column.) He lives in Caracas with his wife, Lourdes, to whom he has been married since 1967. The Blancos had three sons, Ronnie, Randy and Reggie, and a granddaughter: Marisol Elena.

His countrymen view Dámaso Blanco as a very qualified expert in baseball, a great and very responsible worker, a caring human being, and one of the three best defensive third basemen in the history of the Venezuelan winter league.

Grateful acknowledgment to Dámaso Blanco for his memories. Thanks to my SABR colleague Rory Costello for his support as this story took final form.

June 9, 2011

Sources

Gutiérrez, Daniel, Efraim Álvarez and Daniel Gutiérrez, _La Enciclopedia del Beisbol en Venezuela._Liga Venezolana de Béisbol Profesional, 2006.

Gómez, Richard, Campeones. Las Series Finales del Béisbol Profesional Venezolano Fondo Editorial Cárdenas Lares, 1997.

García Giner, Bracho Emil, 99+1. Fundación Magallanes de Carabobo, 1996

Tusa, Alfonso. Una Temporada Mágica. Liga Venezolana de Béisbol Profesional, 2006.

Revista Béisbol, 1978.