Bill Hogg – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Right-handed pitcher Bill Hogg seemed destined for stardom when his 33 wins on the Pacific coast in 1904 earned him a ticket to the New York Highlanders in the American League. Two years later combined with Al Orth and Jack Chesbro to help the Highlanders climb to second place. But like so many other tragic stories in baseball, Hogg was denied success by a nagging physical condition that was sadly viewed at the time as a malingering attitude or possibly a proclivity to imbibe spirits. It was not until his untimely and unexpected death in 1909 that the baseball world realized what he had endured.

Right-handed pitcher Bill Hogg seemed destined for stardom when his 33 wins on the Pacific coast in 1904 earned him a ticket to the New York Highlanders in the American League. Two years later combined with Al Orth and Jack Chesbro to help the Highlanders climb to second place. But like so many other tragic stories in baseball, Hogg was denied success by a nagging physical condition that was sadly viewed at the time as a malingering attitude or possibly a proclivity to imbibe spirits. It was not until his untimely and unexpected death in 1909 that the baseball world realized what he had endured.

William Johnston Hogg was born on September 11, 1881, in Port Huron, Michigan, the second of three children born to William and Adelaide (usually called Addie) Hogg. His parents were both Canadian and had wed in 1879. Adelaide was of Scottish ancestry while her husband was English. They had moved to the United States shortly after the birth of their first child, Andy, in 1880. The elder Hogg worked as an agent for the railroads. The family moved westward across the nation with each new assignment, reaching Pueblo, Colorado around 1890, where Bill’s father served as the head commercial agent for the Missouri Pacific and became quite prominent, eventually becoming involved in the community’s minor league baseball teams.1

The children attended school in Pueblo with Andy and Bill gaining office jobs in the local steel works after their schooling. Bill, who earned numerous nicknames including “Willie**,”** “Billy**,”** and “Piggy**,”** grew to be six feet tall with a weight that fluctuated between 160 and 200 pounds during his career.2 As a right-handed pitcher he “had everything in the line of speed and curves” but “lacked the one great essential, control.”3

Hogg learned the game on the sandlots in Pueblo. Before the age of 18 he was pitching for the town team, sponsored by the Rover Wheel and Athletic Club, which earned the team the name of Rovers.4 In 1900 he was given a trial by the local professional club, the Class B Western League’s Pueblo Indians, against the Sioux City Cornhuskers. Facing a lineup that included veteran Jack Glasscock, the 18-year-old Hogg, “the crack young Pueblo amateur,” stumbled in the first inning with wildness and nervousness and surrendered eight runs. He gained his composure and finished out the game before 500 townspeople, taking the loss, 10-4.5

Pueblo had been a baseball hotbed for a decade. Major league infielder Jimmy Williams had honed his skills there starting in 1892. Williams proclaimed to the baseball world in 1901 that “Hogg has wonderful control of the ball, has an excellent drop and barrels of speed.” He went on to say that he was surprised Hogg had not signed, but suggested that the elder Hogg had opposed signing to that point. Williams let slip, “I think the Kid will think for himself… and seek fame.”6

In 1902 “the Kid” did indeed leave home to join the Seattle Clamdiggers in the Class B Pacific Northwest League. He debuted with them on May 7 and at the end of the month sported a 4-0 record, according to the Seattle Times. On June 12 he received the sad news that his father had died. He traveled back to Pueblo to be with his family and missed nearly a month of the season.

Seattle had gotten off to a fast start, but by the time Hogg returned in July they were in a tight race with Helena and Butte. Hogg took his turn in the three-man rotation until September, when he left the mound in the second inning on September 6 because of a sore arm. He missed his next start before returning to pitch against Portland on September 14, but left that game in the second inning with a broken arm.7 Years later he told a reporter, “Ever since my arm was broken I have caught particular Cain when I exercise my whip strenuously… after I take a full turn in the box I can’t sleep for a couple of nights…there’s no relief.”8

Based on box scores from the Seattle Times, Hogg likely posted a 15-9 record for the Clamdiggers. In 1903, Hogg returned to Seattle, managed by Dan Dugdale, in the newly christened Class A Pacific National League (PNAL). The rival Pacific Coast League (PCL) was considered an outlaw league in 1903. Rumors circulated in early June that Hogg was being courted by the Portland Browns of the PCL.

On June 10, Hogg took the mound against the PNAL Portland club. He was in a foul mood for some reason, quarreling with teammates while walking eight on the way to a 6-3 win. A Portland writer noted that he “sulked like a spoiled baby deprived of the joys of playing in the mud.”9 The next day, Dugdale confronted Hogg, who demanded his release. The incident ended with Dugdale sending Hogg to the “cold, cold ground” with one punch.10 Not surprisingly, Hogg jumped the team to join Portland’s PCL team.

Hogg spent about six weeks with the Browns before he was fined and suspended for a “drunken quarrel on the streets of Portland.”11 He left the team and returned to the PNAL, this time with the Spokane Indians. He lost his first start with them on August 6 to San Francisco.12 Baseball-Reference credits him with a 24-17 record for the wild season.

Hogg opened the 1904 season with Spokane in the four-team PNAL. He battled control problems early in the season, but after consecutive shutouts of Salt Lake City and Boise, his record was 6-4 on June 2.13 He raised that to 16-7 by late July as the Indians crept into first place ahead of Boise.14

The league lead see-sawed until the PNAL season closed on September 25 when Boise cemented their first-place finish with a 21-hit pounding of Spokane. Hogg was not on hand; he had joined several other PNAL players and jumped to Portland of the PC, now managed by Dan Dugdale. Their reunion went smoothly despite Hogg losing his first start to Seattle, 3-1.15 But on October 17, with Portland hopelessly in last place, Dugdale was replaced and Hogg was one of five players released in a team shake-up.16 He and two of the others who were given their walking papers had been drafted by major league teams, Hogg going to the New York Highlanders. He caught on with the Seattle Siwashes in the PCL and played with them into November. Altogether he had chalked up 33 wins.

Hogg joined manager Clark Griffith and the Highlanders for 1905 spring training in Alabama, and quickly attracted the attention of New York sportswriter Allen Sangree with the sharp break on his curve ball. Hogg explained that if a bucking broncho could arch and then explode, why not a baseball. He claimed to have developed the “Broncho Ball” thanks to a “peculiar motion of the wrist [and] hinch of the digits” that produced a sidearm pitch that did not rise but broke down and away.17

Hogg traveled north as a spare pitcher and saw his first action on April 25 when he was summoned to pitch in relief of Walter Clarkson with Washington ahead, 4-2. “He was cool, had lots of speed, good control of his side arm delivery, and whisked the ball over the edges of the plate.”18 He earned the victory, 6-5, when Willie Keeler ended the game with a home run.

Hogg went five innings in his first start but did not earn a decision. His first complete game and shutout ended in a scoreless, 11-inning tie on May 13 in Chicago. Splitting time between the bullpen and starting, he posted a 9-13 record which included shutout wins over Philadelphia and Detroit.

In 1906 he opened in the rotation with Orth and Chesbro. Clarkson and the team’s lone lefty, Doc Newton, saw spot starts. Hogg had seven wins, including two shutouts, heading into a July 19 doubleheader against Cleveland. He had no idea of the controversy that awaited him. The Naps, slightly behind second-place New York in a tight pennant race, took the opener behind an Addie Joss shutout. Hogg was matched against Bob Rhoads in the second game.

The game was a scoreless tie in the third when Naps star third baseman, Bill Bradley, faced Hogg. Bradley stepped into the second pitch thinking it a fastball only to have it break sharply and smash his wrist. Bradley’s season was finished and with it the pennant hopes of the Naps.19 Besides the injury to Bradley, two other Naps were spiked in the game, leading to charges that the Highlanders and particularly Hogg were intentionally looking to inflict damage.

The incidents sparked a claim that Hogg was also gunning for Lajoie. From various accounts it appears that Kid Elberfeld, who was not in the New York lineup that day, may have sparked the controversy with remarks that Lajoie was next.20 Griffith was forced to speak with reporters, including a scribe from the Cleveland Plain Dealer, and pronounced, “No pitcher who ever worked for me hit a batter purposely and I will not tolerate it.”21

Cleveland won the game, 3-2. The next day New York won in a game devoid of confrontation. After the July 19 loss, Hogg’s record stood at 7-5. He ran it up to 14-10 after a shutout of the first-place White Sox on September 23, then closed out the year with three road losses when his teammates only generated one run of support.

Griffith expected his pitching staff to feature Orth, Chesbro, Hogg, and youngster Slow Joe Doyle in 1907. Southpaw Newton was again used as a spot starter. After two no-decisions, Hogg claimed his first win in Boston on May 2. Unfortunately, he was lifted from the game with a sprained shoulder.22 That injury and an illness that followed kept him sidelined until June 12. He returned to the starting rotation in late June and won four of five decisions to make his record 5-2, then fell victim to his own inconsistency and closed out the year with a 10-8 record.

The New York Sun claimed that Griffith had 18 pitchers to choose from in 1908, but that Orth, Chesbro, Hogg, Newton, Doyle**,** and newcomer Fred Glade were the likely candidates.23 Hogg worked to get into condition during spring training and looked to be in good shape when he defeated the Newark Bears on April 12. He struck out nine, allowed only four hits, but did raise a few eyebrows with five walks and two hit batsmen.24

A cold front blew into the region after that and Hogg came down with a sore arm. His inability to take the mound, yet accept a paycheck, irritated team president Frank Farrell. Griffith meanwhile supported his ailing player whom Griffith thought was plagued with a combination of rheumatism and kidney troubles.25 Hogg made his first start on May 26. He went nine innings before being lifted and watched as Newton lost in the tenth. A week later Hogg lost to Boston, 7-0. After that loss, he was suspended without pay for failing to be in proper condition. He was also placed on waivers.

The Tigers placed a claim and the two teams tried to work out a trade, but nothing materialized. Griffith continued to support his man against the wishes of management. After a loss on June 23, Griffith was fired and replaced by Elberfeld. Farrell and Griffith had a number of reasons for their falling out, Griffith’s support for Hogg perhaps being the leading one.26

Unbeknownst to anyone at that time, Hogg was not a sulker or drinker who refused to get into condition as Farrell suggested**;** he truly was battling his physical demons. It wasn’t until Hogg’s sudden death the following winter that the public came to realize that Griffith had been right to support Hogg as he had.

Hogg’s suspension was lifted on July 1 and he soon returned to the starting rotation. Under Elberfeld the Highlanders collapsed and fell into the cellar by mid-July, never to escape. During the stretch from July 23 to August 18 they managed just a single win. Hogg’s August was miserable. He made eight starts and suffered the loss in each of them. In his defense the New York hitters only scored 15 runs in his August games. He closed out the season with a dismal 4-16 record, but that was not the worst on the team as Orth finished 2-13.

The lone highlight of 1908 for Hogg was his marriage to Mathilda Loesch.27 The couple would have one child, Adelaide, who was born on January 9, 1909, in New York City. Hogg ended the year by appealing to the National Commission for the return of the salary he had lost, $319.48, during the suspension. The Commission ruled in favor of the team, leading to a headline: “National Commission Rules That Players Out of Condition Cannot Collect.”28

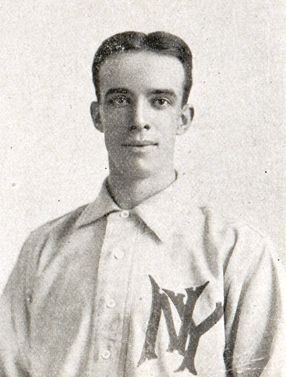

On February 20, 1909, Hogg and outfielder Frank Delahanty were sold to the Louisville Colonels of the American Association. The Louisville newspaper account of the transaction welcoming the new players quoted Clark Griffith as saying, “You cannot get better men.”29 Hogg reported to Louisville on March 12 and quickly signed his contract. Described as “husky**,**” he assured fans that while he had been sick most of 1908, he was now in fine condition and ready to help the team.30A photograph published a few days later showed him as round-faced and looking older than his 27 years.31

Once in town, Hogg got to work with his manager and catcher Heinie Peitz.32 Unfortunately, after just a couple of days he was bedridden with an illness. His conditioning was slowed because of that and he only pitched five scoreless innings in his first exhibition, but fans were thrilled to see his “splendid form” even if he was not yet in top shape.33

Hogg’s first regular-season appearance came on April 17 when he beat Columbus, 6-5. He allowed 11 hits but did not walk a man. Most impressively, he smashed a double down the right-field line to drive home a run.34 He followed that with a 13-inning shutout to cement his place in the pitching rotation. The Colonels would be in the thick of the pennant race all season and emerge as champions. Hogg was second on the club in wins (17) and innings pitched (295).

The team played exhibition games for a couple of weeks after the season. When they concluded, Hogg joined teammate Tom Reilly and headed south to New Orleans. There the duo joined Peter Braquet’s semipro team where Hogg tossed a shutout in his first appearance.35 Focused on impressing scouts and earning his way back to the majors, Hogg took the hill frequently through November but was suddenly bedridden after his November 28 start.

Bill Hogg died on December 9, 1909, from Bright’s disease, which attacks the kidneys and is often accompanied by high blood pressure and swelling (which might explain the roundness of his face in the picture from March). Exactly how long he had suffered with the disease is unknown, but it helped to explain his illnesses in 1907-09. His remains were sent by train to Louisville with Reilly accompanying Hogg’s wife on the journey.36 From there the family traveled to New York where Hogg was buried in Lutheran All Saints Cemetery in Queens on December 12. Clark Griffith was reported to have attended the funeral.

Mathilda and Adelaide Hogg remained in New York living with Mathilda’s mother. In April, Hogg’s mother, Addie, filed suit against William’s insurance company for the benefits of his life insurance policy.37 Whatever became of that litigation is unknown because Addie died suddenly in June. Many newspapers emblazoned headlines saying she died of grief.38

Sources

Baseball Reference and Retrosheet were used for statistics (unless otherwise noted). Ancestry.com was consulted for family background.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by William Lamb and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 “Pueblo Players Report,” The Sporting News, March 20, 1900: 1.

2 Baseball Reference lists him at 200. However, the New York Sun from January 14, 1907 (page 7) says he ended 1906 at 160 and started 1907 at 180. It should also be noted that the nickname Buffalo Bill was attributed to Hogg. This appears to have been a creation of a newspaper story in the 1980s and was not found in use by this author during Hogg’s lifetime.

3 “Good Pitcher Lost in “Piggy” Hogg,” Anaconda (Montana) Standard, December 22, 1909: 2.

4 “Sacred Concert Opens Pageant,” Rocky Mountain News (Denver, Colorado), July 3, 1899: 3.

5 “Hogg Rattled in the First,” Rocky Mountain News, August 7, 1900: 6.

6 “Keep Your Eyes on Hogg,” Rocky Mountain News, November 26, 1901: 8.

7 “Hogg Breaks His Arm,” Seattle Times, September 15, 1902: 11.

8 Willie Hogg Has Trouble,” Chronicle (Spokane, Washington), April 11, 1908: 17.

9 “Batting the Hot Air,” Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), June 11, 1903: 6.

10 “Willie Hogg Jumps Dug,” Seattle Star, June 13, 1903: 2.

11 “Hogg in Disgrace,” Seattle Star, August 3, 1903: 2.

12 “San Francisco 5, Spokane 1,” Seattle Times, August 7, 1903: 5.

13 “Their Work in Fielding,” Anaconda Standard, June 5, 1904: 10.

14 “Helena Team Wins Game,” Anaconda Standard, July 25, 1904: 8

15 “Pacific Coast League,” Anaconda Standard, September 26, 1904: 8.

16 “Ike Butler in Charge of Team,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 18, 1904: 8.

17 Allen Sangree, “Batsmen, Beware!” Evening World (New York), March 20, 1905: 8.

18 “Keeler’s Homer Won,” Washington Post, April 26, 1905: 4.

19 “Bill Bradley’s Arm Broken,” Buffalo Enquirer, July 20, 1906: 8.

20 “Ugly Charges in Big Leagues,” Minneapolis Journal, July 21, 1906: 4.

21 “Prompt Denial from Griffith,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 21, 1906: 6.

22 “American League,” New York Times, May 3, 1907: 8.

23 “American League for 1908,” New York Sun, January 12, 1908: 26.

24 “Yankees Beat New York,” New York Tribune, April 13, 1908: 8.

25 “Hogg’s Ill Luck,” Sporting Life, December 18, 1909: 2.

26 “Forced to Quit,” Sporting Life, July 25, 1908: 7.

27 An exact wedding date has not been discovered. The identification of Mathilda and Adelaide was made possible by a picture in the Brooklyn Times Union on March 31, 1924: 10. It showed Oceanside Long Island high school girls’ basketball team and identified Adelaide Hogg as the daughter of the late pitcher Billy Hogg. From there ancestry.com provided the additional information.

28 “Players Must Be in Shape to Get Salary,” Buffalo Courier, December 25, 1908: 8.

29 “New Players Are Secured,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), February 21, 1909: 28.

30 “Pitcher Hogg Reports to Duty for the Colonels,” Courier-Journal, March 12, 1909: 7.

31 “Hogg Pitcher,” Courier-Journal, March 19, 1909: 9.

32 “Heinie Peitz Now Manager,” Courier-Journal, February 14, 1909: 29.

33 “Chat of the Game,” Courier-Journal, April 8, 1909: 8.

34 “Four Straight for Colonels,” Courier-Journal, April 18, 1909: 33. Hogg only had three extra-base hits in his major league career.

35 “In Pretty Game, Braquets Beat the Beavers-One to Nothing,” Times-Democrat (New Orleans), November 1, 1909: 13.

36 “Hogg’s Remains Arrive To-Day,” Courier-Journal, December 10, 1909: 6.

37 “Mother Sues for Insurance,” (Butte, Montana) Post, April 4, 1910: 6.

38 “Greif Causes Death of William Hogg’s Mother,” San Francisco Call, June 13,1910: 2.