Chris Hartje – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

Chris Hartje’s fleeting big-league career consisted of nine games with the 1939 Brooklyn Dodgers. In 16 at-bats, the right-handed hitting catcher recorded five hits and just as many runs batted in. Hartje, who served in the United States Coast Guard during World War II, was attempting to resurrect his professional baseball career with the Spokane Indians in 1946 when he died from injuries sustained in the team’s tragic bus accident in the Cascade Mountains.

Chris Hartje’s fleeting big-league career consisted of nine games with the 1939 Brooklyn Dodgers. In 16 at-bats, the right-handed hitting catcher recorded five hits and just as many runs batted in. Hartje, who served in the United States Coast Guard during World War II, was attempting to resurrect his professional baseball career with the Spokane Indians in 1946 when he died from injuries sustained in the team’s tragic bus accident in the Cascade Mountains.

Christian Henry Hartje was born on March 25, 1915, in San Francisco, California. His parents, Dietrich and Marie (née Meyer), immigrated from Germany in the late 1800s and had 11 children.1 According to the 1920 census, Dietrich worked as a laborer at the American Can Company.2

Hartje first made a name for himself on the baseball diamond as a 17-year-old catcher for a semipro team in the Golden Gate Valley League. Red Adams, who filled dual duties of athletic trainer and scout for the Mission Reds of the Pacific Coast League, discovered Hartje and signed him to a professional contract in November 1932.3 Hartje, who had light-brown hair and blue eyes, trained with Mission under manager Fred Hofmann in the spring of 1933 but did not crack the opening day roster. He then returned to the semipro circuit for a team sponsored by Baumgarten Brothers Butchers.4

New York Yankees scout Joe Devine signed Hartje in January 1934.5 The prospect was farmed out to the Wheeling (West Virginia) Stogies in the Middle Atlantic League (Class C), where he posted a .279 batting average in 111 at-bats. He began 1935 by going to spring training with the Oakland Oaks of the Class AA Pacific Coast League and made the team as a backup catcher. Hartje appeared in 14 games before being sent to the Akron (Ohio) Yankees—New York’s new Middle Atlantic League affiliate. In 28 games, he hit .226 and swatted three home runs.

Hartje had a breakout campaign with the Oaks in 1936, hitting .323 in 103 games while sharing catching duties with Willard Hershberger. A year later, the Yankees elevated Hartje to their top affiliate—the Class AA Kansas City Blues of the American Association. The 22-year-old continued to impress, registering a .292 batting average with 17 doubles, two triples, and four home runs as the Blues’ primary catcher.

The Yankees optioned the 5’10, 165-pound catcher to their Newark affiliate before the 1938 season. He missed time during spring training after taking a foul tip to the finger and was sent back to Kansas City when the season began.6 In what would become a recurring theme during his career, some in baseball circles questioned Hartje’s commitment to the game. “The only adverse criticism we have heard of this young man, who was with the Blues last year, is that he is not inclined to regard his work seriously enough,” wrote the Kansas City Star.7

Hartje hit .289 in 44 games with the Blues and was rewarded with a spot on the circuit’s All-Star team along with teammates Eddie Joost and Eddie Miller and a Minneapolis Millers outfielder named Ted Williams. The exhibition would pit the All-Stars against the league-leading Indianapolis Indians on July 14.8 On July 7 Hartje, already out of the lineup with an injured finger, flew from Toledo, where the Blues were playing, to California, reportedly because of the death of his mother.9 Because Marie Hartje did not die until 1952, this report was either erroneous, or Hartje, who was often described as homesick, made up the story as an excuse to go to the West Coast.10 Hartje never returned to Kansas City; in early August, he was optioned to the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League, where he appeared in 10 games.

Hartje had proven himself a legitimate prospect in the Yankees’ chain, but he was blocked by perennial All-Star catcher Bill Dickey. The Bronx Bombers cashed in on their expendable young catcher in February 1939, selling Hartje, along with Kemp Wicker and minor-leaguer Jack LaRocca, to the Dodgers for $50,000.11 Hartje joined his new organization for spring training in Clearwater, Florida. Manager Leo Durocher, known for his fiery temper and hard-nosed style of play, assessed that his new catcher “seemed lazy” and failed to show fight and pep.12 The skipper told him, “It’s all right with me if you want to stay in the minors and work for peanut money.”13 After this underwhelming first impression, the Dodgers optioned Hartje to the Montreal Royals of the International League. He performed well north of the border, hitting .296 with three home runs and 43 RBIs in 420 plate appearances. Hartje credited his manager, Hall of Fame pitcher Burleigh Grimes, with helping him improve. The Dodgers called up Hartje in early September after catcher Babe Phelps suffered a fractured thumb.

Hartje made his big-league debut on September 9, 1939, as a pinch-hitter versus the New York Giants at Ebbets Field. The Dodgers trailed, 3-2, and had runners at the corners with no outs in the bottom of the eighth inning. Durocher sent Hartje up to hit for the lefty swinging Art Parks against southpaw Cliff Melton. Hartje pulled a line drive down the left-field line for a double that scored the tying and go-ahead runs. The Dodgers held on to win, 8-3.

Five days later, Hartje received his first starting assignment in the second game of a twin bill at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. Hitting seventh in the order, the rookie recorded three singles in four at-bats and picked up his third RBI. “He has that fight and pep that he lacked last spring,” observed Durocher.14 Hartje was hitless in his next 10 at-bats before ending his season with another two-run single off the bench in the Dodgers’ 22-4 rout of the Philadelphia Phillies on September 23.

Hartje’s brief big-league success gave him confidence heading into the offseason. “I’m going to make this club as a regular next year,” he declared.15 His prediction failed to come to fruition, however. In 1940 he was sent back to Montreal. Marc McNeil of the Montreal Gazette explained why Dodgers general manager Larry MacPhail had “soured” on Hartje: “Usually Chris laughs all the time, for life to him is one long joke. He takes practically nothing seriously. That is why he is not sticking up in the major leagues, although he is a pretty good ballplayer.”16

Besides Hartje’s carefree attitude, he developed a reputation as someone who enjoyed the nightlife. The Dodgers wanted to jettison Hartje from the organization, but Montreal’s new manager, Clyde Sukeforth, lobbied to keep Hartje on his team. “Sukeforth is fully aware that Chris likes his beaker of beer and is inclined to break curfew,” wrote McNeil.17 Nevertheless, the Royals’ new pilot expressed confidence that he could handle Hartje and get him back to the major leagues. But when the regular season got underway, Hartje was relegated to a backup role behind Joe Becker. The May 30 edition of the Montreal Star reported that Hartje was homesick. Five days later, the Royals sold him to the Syracuse Chiefs, where he hit .279 through the remainder of the season.18

Hartje returned to Syracuse in 1941. In one game, he played through excruciating abdominal pain, at one point calling timeout because of nausea.19 After the game, he was diagnosed with appendicitis and underwent surgery. Hartje’s tenacity that day contradicted previous reports that questioned his effort. He ended the campaign with a .228 average in 158 at-bats.

After another season with the Chiefs during which he hit only .141 in 156 at-bats as a reserve, Hartje enlisted in the Coast Guard in March 1943. He was stationed in Alameda, California, just across the bay from his hometown. On Sundays, he played for the Coast Guard Sea Lions in an all-service league that featured a number of major leaguers. Hartje was discharged from the Coast Guard on September 26, 1945, with a rank of Seaman First Class.

In early 1946, Hartje was poised to revive his professional baseball career. He signed with Casey Stengel’s Oakland Oaks on February 22 and reported to the team’s spring training camp in Boyes Springs, California.20 The Oaks roster, like many teams across professional baseball, was loaded with returning servicemen attempting to resume their baseball careers following the end of World War II. Stengel cut Hartje in mid-March after a brief audition. “It wasn’t that he didn’t make the grade,” wrote Emmons Byrne in the Oakland Tribune, “but that the club had three pretty fair catchers in Billy Raimondi, Eddie Kearse, and Will Leonard.”21 The Oaks kept a number of higher-profile returning veterans in hopes of selling them to the highest bidder.

In June Hartje signed with the Spokane Indians of the Class-B Western International League, joining a talented team that included former Brooklyn Dodger Ben Geraghty, San Diego Padres farmhand Jack Lohrke, and Vic Picetti—widely considered one of the best prospects on the West Coast.

Hartje made his Spokane debut on June 20 against the visiting Salem Senators. He made a strong first impression, delivering a two-run single and drawing a pair of walks. “His hustle was something the Indians can certainly use and his job handling [pitcher Milt] Cadinha left nothing to be desired,” wrote the _Spokesman-Re_view.22 Hartje went 1-for-4 with a double the following day and made his third start in the first game of a doubleheader on Sunday, June 23. He stroked another double but had to leave the contest after taking a foul ball to the knee.23

The next morning the Indians departed Spokane, in eastern Washington, by bus for their next series across the state in Bremerton. While the team ate dinner in Ellensburg, Lohrke got word that the Padres were recalling him to San Diego and caught a ride back to Spokane. The rest of the team continued west to Bremerton. About an hour later, the bus reached Snoqualmie Pass and began to descend the western slope of the Cascades when an approaching vehicle forced the bus off the road. The bus broke through the wire guard, careened 300 feet down a steep, rocky embankment, and caught fire. Several players were thrown out of the bus, including Hartje, who sustained severe burns. Six players were pronounced dead at the scene and Picetti died on the way to the hospital. An eighth player, George Lyden, died the next day. Hartje was treated at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, where he was covered head to toe in gauze except for slits for his eyes and mouth. A horrific photo of him in his hospital bed ran in the June 25 edition of the Spokane Chronicle.24

On June 26, Hartje, 31, succumbed to his third-degree burns, becoming the ninth player to die as a result of the crash. He was buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California. His wife, the former Grace “Holly” Wolff, was pregnant with their first child when Chris died. She gave birth to a daughter, Christine, later that summer. Grace eventually remarried John “Dutch” Anderson, a San Francisco pressman and Spokane Indians trainer who was not on the deadly bus trip. Anderson later had a long scouting career with the San Francisco Giants. He and Grace had a daughter named Caren in 1951.

As of 2024, the Spokane Indians tragedy remains the deadliest accident in the history of American professional sports.

Author’s note

This article was derived from the author’s research for the book, Season of Shattered Dreams: Postwar Baseball, the Spokane Indians, and a Tragic Bus Crash That Changed Everything (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2024).

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Tony Oliver. Some information used in this biography was provided to the author via an interview with Caren Sutton, the daughter of John Anderson and Grace Wolff Hartje Anderson.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com.

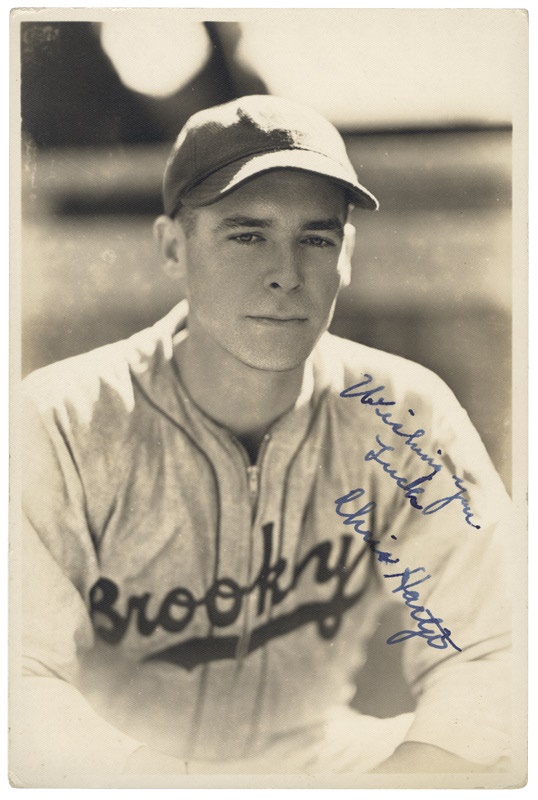

Photo credit: Courtesy of the author.

Notes

1 Dietrich Hartje Obituary, San Francisco Examiner, October 17, 1935: 13.

2 1920 United States Federal Census for Detrich [_sic_] Hartje, https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4293842-00010?pId=98495017.

3 “Young Player Signs Contract with Missions,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 30, 1932: 12.

4 James J. Nealon, “Seals Stadium Double Program Starts at 1 P.M.,” San Francisco Examiner, March 6, 1934: 24.

5 “S.F. Sandlot Tossers Signed,” San Francisco Examiner, January 24, 1934: 21.

6 “The Blues Get Hartje,” Kansas City Star, April 5, 1938: 12.

7 “Hearts are Favorite Indoor Sport of the Blue Player,” Kansas City Star, April 6, 1938: 10.

8 “Association All-Star Club Well Balanced,” Wisconsin State Journal, July 5, 1938: 14.

9 “Silvestri to Replace Hartje Against Trice, Indianapolis Star, July 10, 1938: 19. “Hartje’s Mother is Dead,” Kansas City Star, July 7, 1938: 10; “Chris Hartje’s Mother Dies in San Francisco,” Kansas City Journal-Post, July 7, 1938: 8.

10 “Foul Tips,” Los Angeles Times, August 4, 1938: 28.

11 Hy Turkin, “Dodgers Spend $50,000 for 3 Yank Farmhands,” Daily News (New York), February 7, 1939: 247.

12 Harold Parrott, “Basque Second Sacker No Longer Tabbed as ‘Nice-Nelly’ Ball Player,” _Brooklyn Daily Ea_gle, September 15, 1939: 18.

13 Parrott, “Basque Second Sacker No Longer Tabbed as ‘Nice-Nelly’ Ball Player.”

14 Parrott, “Basque Second Sacker No Longer Tabbed as ‘Nice-Nelly’ Ball Player.”

15 Parrott, “Basque Second Sacker No Longer Tabbed as ‘Nice-Nelly’ Ball Player.”

16 Marc T. McNeil, “Casual Closeups: Happy-go-lucky Hartje,” (Montreal) Gazette, April 23, 1940: 14.

17 McNeil, “Casual Closeups: Happy-go-lucky Hartje.”

18 Bill Reddy, “Syracuse Chiefs Need Comeback by Veterans,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 10, 1941: 27.

19 Caren Sutton interview with the author, February 24, 2023.

20 Clyde Giraldo, “Pippen Refuses $850 Acorn Offer,” San Francisco Chronicle, February 23, 1946: 13.

21 Emmons Byrne, “Hartje Cast Adrift by Oaks Manager,” Oakland Tribune, March 15, 1946: 10.

22 “Spokane Wins from Salem,” Spokesman-Review, June 21, 1946: 14.

23 “Spokane Wins Salem Series, 4-3,” Spokesman-Review, June 24, 1946: 7.

24 “Seriously Injured,” Spokane Chronicle, June 25, 1946: 2.