Jack Meyers – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

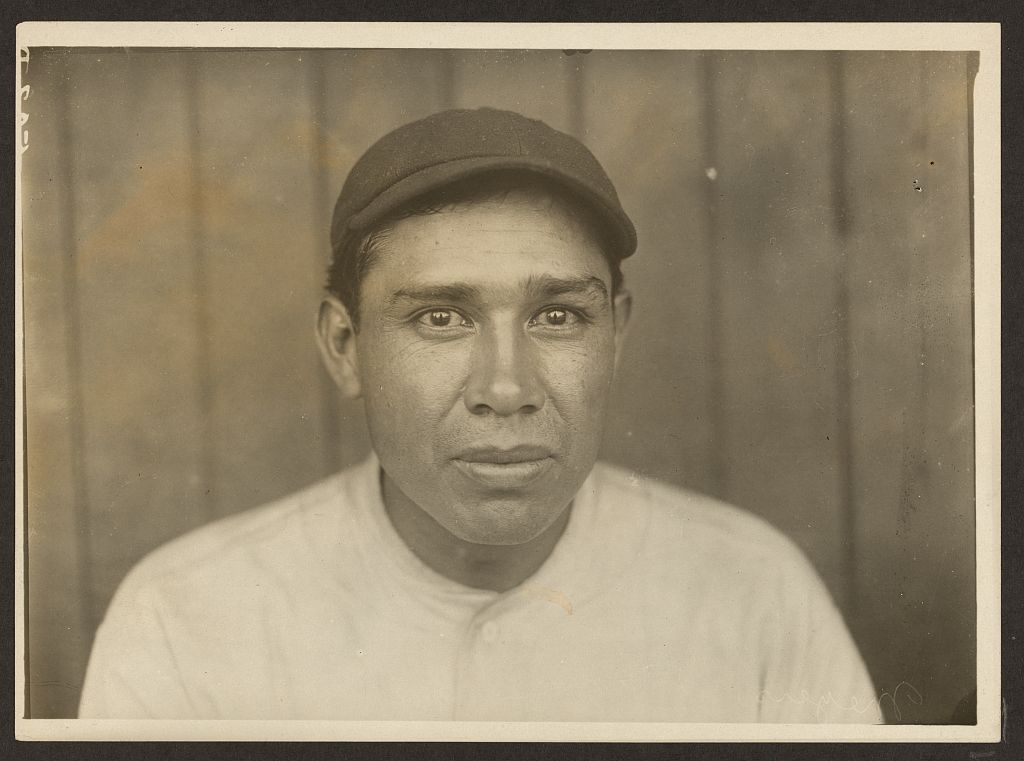

As a Native American playing in the Deadball Era, Jack Meyers couldn’t avoid being saddled with the nickname “Chief,” but he did as much as any Native American of his generation to shatter the stereotypical image of the dumb Indian. Meyers was far more sophisticated than most of his fellow players. “A strong love of justice, a lightning sense of humor, a fund of general information that runs from politics to Plato, a quick, logical mind, and the self-contained, dignified poise that is the hallmark of good breeding-he is easily the most remarkable player in the big leagues,” wrote one reporter. On the field, the strong but slow-footed Meyers was almost certainly the best offensive catcher of the Deadball Era, retiring with a .291 average for his nine-year career.

As a Native American playing in the Deadball Era, Jack Meyers couldn’t avoid being saddled with the nickname “Chief,” but he did as much as any Native American of his generation to shatter the stereotypical image of the dumb Indian. Meyers was far more sophisticated than most of his fellow players. “A strong love of justice, a lightning sense of humor, a fund of general information that runs from politics to Plato, a quick, logical mind, and the self-contained, dignified poise that is the hallmark of good breeding-he is easily the most remarkable player in the big leagues,” wrote one reporter. On the field, the strong but slow-footed Meyers was almost certainly the best offensive catcher of the Deadball Era, retiring with a .291 average for his nine-year career.

A member of the Cahuilla tribe, also called the Mission Indians, John Tortes Meyers was born on July 29, 1880, in Riverside, California. Because Jack’s father died when he was only seven years old, his mother, Felicite, became the most important influence in his early life. Meyers attended Riverside High School and played semipro baseball throughout the Southwest. During the summer of 1905 he was catching in a tournament in Albuquerque when he caught the attention of a rival player named Ralph Glaze. A baseball and football standout at Dartmouth College who later made the majors as a pitcher with the 1906-08 Boston Americans, Glaze thought the 5’11”, 194-pound catcher could help his college team on both the gridiron and the diamond. Pointing out that the school’s charter provided for the education of Native Americans, Glaze convinced Dartmouth alumni in his hometown of Denver to equip Meyers with cash, railroad tickets, and even an altered diploma because Meyers hadn’t completed high school.

With the assistance of a tutor, Meyers attended classes at Dartmouth during the 1905-06 school year and enjoyed his time there immensely, but college administrators discovered that his high-school diploma was false. They offered to admit him if he completed a preparatory program, but when school let out the 25-year-old catcher instead signed a contract with Harrisburg of the independent Tri-State League. The Harrisburg team “certainly laid themselves to make me a happy Indian,” Jack told a reporter in 1909. “I went to the clubhouse and nobody paid more attention to me than they did to the bat bag.” Finally getting into a game on Independence Day, Meyers was assigned to catch a spitballer named Frank Leary who pitched a couple games for the Cincinnati Reds the following season. “I was getting it everywhere but my glove,” he recalled. “I had five passed balls in two innings.” Leary was intentionally crossing up Meyers, who finally stopped putting down signs. “Do you know, that did me more good than anything that ever happened to me?” Chief recalled. “It made me mad. I had been timid and now I was mad enough to be brave.”

Meyers’ career took off after he found the courage to stand up to those who derided him. After spending 1907 in the Northwestern League with Butte and 1908 with St. Paul of the American Association, Chief found himself in New York City as a 28-year-old rookie with the Giants at the end of the tumultuous 1908 season. He failed to appear in a single game, but that winter the Giants traded Roger Bresnahan to the St. Louis Cardinals. The following year Meyers shared the catching duties with Admiral Schlei, and in 1910 he became a regular, batting .285 to establish himself as one of the best-hitting catchers in the game.

The press, in New York and elsewhere, took an immediate liking to Meyers because he made more interesting copy than his teammates. During rainouts or off-days, while the other players holed up playing cards or billiards, newspapers reported that Meyers would go out to do some historical sightseeing or watch a local college football team practice. In Boston, wrote Bozeman Bulger, Meyers made a point of visiting the art museums where he spent hours touring the exhibits. Several writers noted that his favorite painting was “Quest for the Holy Grail,” the mural by Edwin Austin Abbey that hangs in the Boston Public Library.

After only two years in the majors, Meyers was popular enough for the vaudeville circuit. At Hammerstein’s Victoria Theatre on October 23, 1910, Meyers teamed up with Christy Mathewson in a vaudeville sketch entitled “Curves.” Written by Bulger and produced by actress May Tully, the half-hour sketch featured the battery in a scene set at the Polo Grounds, with Tully playing an ardent spectator. The players, in their home uniforms, demonstrated for Tully and the audience how to throw various pitches, and Meyers explained the workings of the catcher. Tully then returned the favor by convincing Mathewson and Meyers to join her in vaudeville and by teaching them to act, which, according to Variety, “brings out a travesty drama with Meyers as the ‘bad Indian.’ Mathewson is the cowboy who comes to the rescue of the forlorn maiden and overcomes the ‘bad Indian’ by hitting him in the head with a baseball.” Today it sounds as improper as a blackface minstrel show, but at the time Variety called it a “most satisfactory vehicle.” The act toured the vaudeville circuit for several weeks.

From 1911 to 1913 Meyers finished in the Top 10 each year in Chalmers Award voting for the NL’s most valuable player. In 1911 he led the Giants in batting for the first of three consecutive seasons with a .332 average, third highest in the National League. “Meyers has become the deepest student of batting on the team,” wrote a New York Times reporter after watching him correctly predict the type of pitches thrown by Pirates phenom Marty O’Toole. The next year Chief hit for the cycle on June 10 en route to a career-high six home runs and a .358 average, second in the NL behind only Heinie Zimmerman’s .372. His hot hitting continued in the 1912 World Series, when he started all eight games and batted .357. Meyers remained one of the Giants’ best hitters through the 1914 season, when he batted .286 in a career-high 134 games.

Playing in over 100 games for the sixth consecutive season, the 35-year-old Meyers batted just .232 in 1915, and the Giants placed him on waivers. Both Brooklyn and Boston claimed him, and the Robins won his rights on a coin flip. In Brooklyn Meyers was reunited with ex-Giants Rube Marquard, Fred Merkle, and his mentor, Wilbert Robinson, the former Baltimore Orioles catcher. He remembered the 1916 Robins as “just outsmarting the whole National League” on their way to the pennant, but he batted just .247 in 80 games and knew that he was nearing the end. “I cheated a little on my age so they always thought I was a few years younger,” Chief recalled, “but when the years started to creep up on me I knew how old I was, even if nobody else did.” He split the 1917 season between Brooklyn and Boston, on the latter club replacing Hank Gowdy, the first active major leaguer to enlist for service in World War I, before joining the U.S. Marine Corps himself.

After receiving his discharge in 1918, Meyers joined the Buffalo Bisons, managed by his former Giants teammate Hooks Wiltse, and batted .328 in 65 games. He started the following year as player-manager for New Haven in the Eastern League but was replaced in midseason by Danny Murphy, whom he had played against in the 1911 World Series. Meyers was catching for a semipro team in San Diego in 1920 when the crowd booed him and he decided to quit baseball altogether. He returned to the Riverside area and became a police chief for the Mission Indian Agency. Meyers also worked for the Department of the Interior as an Indian supervisor. His nephew, Jack Meyers, remembered his namesake performing “Casey at the Bat” for children’s groups around the Santa Rosa reservation. “He could be very theatrical and entertaining,” recalled his nephew. Meyers was a favorite at old-timers games for both the Dodgers and the Giants for many years, especially after those teams moved to California. Meyers passed away on July 25, 1971, in San Bernardino, California.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s, Inc., 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Sources

In preparing this article, I made use of many issues of the New York Times, The Sporting News, and Sporting Life, for the years 1909 through 1915. In addition, I relied on the following:

The Desert Sun Online website (http://www.thedesertsun.com) ran an article about Meyers in November 2001. The article is no longer available for free, but is probably available in the paid archive.

THE BASEBALL CHRONOLOGY web site (http://www.baseballlibrary.com/baseballlibrary/chronology/)

Buie, Earl L. Column, San Bernardino (California) Sun-Telegram, April 5, 1961.

Bulger, Bozeman. Twenty-Five Years in Sports, Part II. Saturday Evening Post. May 12, 1928 (Vol. 200, Issue 46).

George, Steve. “Chief Meyers, Unrecognized and Almost Forgotten, Emerges from Out of Games Early Memory Book.” The Sporting News, March 26, 1932..

Lane, F.C. “The Greatest of All Catchers.” Baseball Magazine. February 1913 (Vol. 10, Issue 4).

Lenkey, John. “Chief Meyers Hale and Hearty at 86.” The Sporting News, January 14, 1967, p 14.

Lieb, Fred, column, March 3, 1932, source unknown.

Los Angeles Times, 8/13/1947.

McGreal, Jim. “They Call Him ‘Pitcher’.” Baseball Research Journal. SABR, 1986 .

Oxendine, Joseph B. American Indian Sports Heritage. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics, 1988.

Povich, Shirley. Column, Washington Post, August 18, 1952.

Powers, Francis J. Chicago Daily News, January 12, 1945, p. 12.

Ritter, Larry. The Glory of Their Times. MacMillan, 1966.

Smith, Chester L.. Column, undated, from The Sporting News archives

“McGraws Indian Catcher Started Out to Become a Civil Engineer”. St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 29, 1909

Sullivan, Prescott. Undated article from The Sporting News archives.