Clyde Sukeforth – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

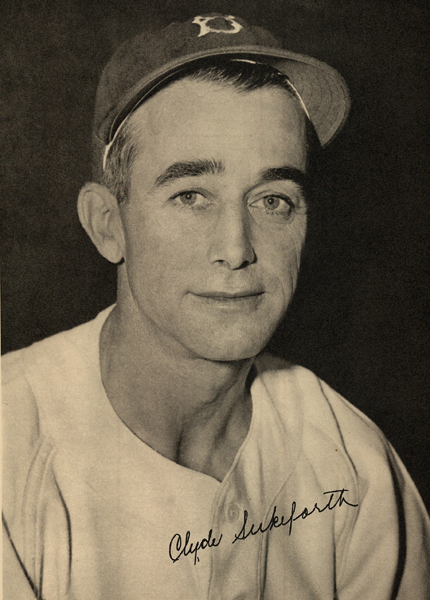

Clyde Sukeforth was a backup catcher who played parts of ten seasons in the Major Leagues for the Cincinnati Reds and Brooklyn Dodgers. Over those ten seasons, Sukeforth hit .264 with only two home runs and had ninety-six runs batted in. Although his accomplishments as a player were minimal, Sukeforth’s subsequent years as a minor-league scout and big-league coach led him to play key roles in three momentous baseball events: the discovery of Jackie Robinson, the signing of Roberto Clemente, and the decision to send in Ralph Branca to pitch to Bobby Thomson, a decision that led to Thomson’s 1951 “Shot Heard ‘Round the World.”

Clyde Sukeforth was a backup catcher who played parts of ten seasons in the Major Leagues for the Cincinnati Reds and Brooklyn Dodgers. Over those ten seasons, Sukeforth hit .264 with only two home runs and had ninety-six runs batted in. Although his accomplishments as a player were minimal, Sukeforth’s subsequent years as a minor-league scout and big-league coach led him to play key roles in three momentous baseball events: the discovery of Jackie Robinson, the signing of Roberto Clemente, and the decision to send in Ralph Branca to pitch to Bobby Thomson, a decision that led to Thomson’s 1951 “Shot Heard ‘Round the World.”

Clyde Leroy Sukeforth was born on November 30, 1901, in Washington, Maine, a tiny rural town. His father was Pearle Leroy Sukeforth, who as a young man was a cooper, but later became a dairy farmer. Clyde’s mother was Sarah M. Grinnell, known as Sadie. Pearle and Sarah were married in May 1899 and had their first child, a daughter Hazel, in November 1899.

The Sukeforths received out-of-town news only from the Boston Post, which was delivered by stagecoach every evening to the local library. From the time he was a young boy, Sukeforth journeyed to that library to read about his favorite baseball players. Most of those players were members of the Boston Red Sox, who just happened to be the best team in baseball during Clyde’s adolescent years.

But Sukeforth did not just read about the game; he played it whenever he got the chance in the brief summers of southern Maine. “Every kid played baseball in my day. That’s all there really was to do. There was no organization to it, but we played seven days a week. And every kid had a ball and a glove,” Sukeforth said in a 1991 interview.

In 1916 Sukeforth enrolled in the Coburn Classical Institute, a college preparatory high school in nearby Waterville. By the end of World War I Maine had become one of the leading paper-manufacturing states in the nation. Massive sawmills, pulp mills and paper plants popped up around the state, creating jobs, and giving rise to a number of company-sponsored baseball teams. After graduating from high school, Sukeforth played two seasons for the Great Northern Paper Company, in Millinocket, Maine. He later recalled, “They recruited all of the better players around, they paid us more than the good ballplayers were getting in the minor leagues.”1

After playing two years for Great Northern, Sukeforth enrolled at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., in the fall of 1923. During his two years at Georgetown, Clyde starred on the school’s baseball team as a catcher and left fielder. He also continued to follow the major leagues, keeping a close watch on the local Washington Senators. In 1924 Sukeforth watched from the stands as Washington’s Walter Johnson pitched against the New York Giants in the World Series.

In 1926 Sukeforth went to spring training with the Cincinnati Reds. He showed well but was sent down to play for the Nashua Millionaires of the Class B New England League. The Reds recalled him in late May, and he made his big-league debut on May 31, when he struck out as a pinch-hitter for Eppa Rixey. That was the extent of Sukeforth’s stay with the Reds. After appearing in four games for the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, he spent the rest of 1926 with the Manchester Blue Sox of the New England League.

During the next two years, 1927 and 1928, the left-handed hitting Sukeforth served as the backup to the Reds’ longtime starting catcher, Bubbles Hargrave. During those two seasons, he played in seventy-one games, batting .162 with five RBI. Sukeforth had his first major-league hit on May 21, 1927, a double off Philadelphia’s Alex Ferguson.

In 1929 Sukeforth had the best season of his career. Playing for a Reds’ team that finished in seventh place, he batted .354 with thirty-three RBIs in eighty-four games. In 1930 he played in ninety-four games, and batted .284. Although the five-feet-ten, Sukeforth weighed only 155 pounds, he caught 106 games in 1931, with a .256 batting average. He also committed thirteen errors, the most by a National League catcher that season.

On November 16, 1931, Sukeforth was accidentally shot in the eye while rabbit hunting. At first, doctors thought he would never be able to play ball again, and even feared he might lose the eye. But his eye improved quickly enough that he was released from the hospital on December 2. Sukeforth’s only complaint about the injury, revealed in interviews years after the fact, was that he “couldn’t read too well without squinting.”2

On March 14, 193, the Reds traded Sukeforth, second baseman Tony Cuccinello and third baseman Joe Stripp, to the Brooklyn Dodgers for three players, including future Hall of Fame catcher Ernie Lombardi. Sukeforth’s played in 106 games as a backup catcher for the Dodgers over the next three years. After the 1934 season the Dodgers optioned him to the Toledo Mud Hens, but he decided he did not want to play in the American Association for the money offered. While mulling his future, Clyde played semipro ball in Maine during the summer of 1935. He was, however, still under contract with Brooklyn, which decided that he might work out well as a manager of one of their lower-level minor league clubs.

So in 1936 Sukeforth managed the Leaksville-Draper-Spray Triplets of the Class D Bi-State League to a third-place finish. He also caught in fifty-one games and hit .365 with seven home runs.

In 1937 Sukeforth managed the Clinton (Iowa) Owls of the Class B Three-I League to a first-place finish. He spent the next two seasons with Elmira in the Class A Eastern League. In 1938 Elmira won the league championship in the post-season playoffs. He also continued to play, appearing in twelve games in 1938 and thirty-one games in 1939. Sukeforth’s success led to a promotion to manage the Dodgers top farm team, the Montreal Royals in the International League.

After Clyde spent three years with Montreal, Brooklyn’s new general manager Branch Rickey, hired him to serve on the Dodgers’ coaching staff in 1943. In 1945, at the age of forty-three, he played in eighteen games for the Dodgers to fill a void created by the player shortages of World War II. He played surprisingly well, hitting .294 in fifty-one at-bats.

Sukeforth’s main job that season, however, was as a scout for Rickey. His most important target was a twenty-six-year-old African American player named Jack Roosevelt Robinson. “Mr. Rickey had sent me to Chicago to see Robinson play. Mr. Rickey wanted me to check Robinson’s arm.”3 However, Robinson had suffered an arm injury and was out of the lineup. Sukeforth introduced himself to Robinson and told him Rickey wanted to meet with him in New York. Robinson agreed to make the trip.

When they arrived in New York, Sukeforth took Robinson to the Dodgers offices in Brooklyn, where he met with Rickey. Sukeforth stayed in the room for the conference between the two men. It was August 28, 1945. Rickey told Jackie that the plan was to have him play for Montreal in 1946. Then, if everything worked according to schedule, he would bring Robinson to Brooklyn.

The 1946 season was a busy one for Sukeforth. He served on manager Leo Durocher’s coaching staff, performed special scouting assignments for Rickey, and, perhaps most importantly, helped create the new Nashua Dodgers of the Class B New England League. In that role, Sukeforth was instrumental in forging ties with the New Hampshire community, and eased the racial integration of the league by adding Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe to the roster.

Prior to the start of the 1947 season, Durocher was suspended for the entire year by Commissioner Happy Chandler for consorting with gamblers. Rickey asked Sukeforth to take over as manager, but Sukeforth did not want the job. He did, however, fill in for the first two games of the season, the first of which featured the debut of Robinson. “I didn’t tell Jack anything special [before the game],” he recalled. “Jack had enough to think about.”4

On April 18, before the game against the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds, the Dodgers announced that Burt Shotton, a longtime Rickey favorite, had been hired as manager. After two games as the manager, Sukeforth was again a coach.

Four and a half years later, Sukeforth played a key role in another memorable moment in baseball history. On October 3, 1951, the Dodgers and the New York Giants played the final game of a three-game playoff to determine who would meet the Yankees in the World Series. At the time, Sukeforth was the Dodgers’ bullpen coach.

“I was the bullpen coach catching the two relief pitchers who were warming up for the Dodgers at the time. Don Newcombe had been throwing pretty good for the Dodgers during the game. He had pretty good control of the game until that ninth inning [when he began to tire]. So I began catching Carl Erskine and Ralph Branca in the bullpen. I didn’t think that Erskine was throwing as good as Branca was that day. Then came the call from the manager (Charlie Dressen). He wanted to know who was throwing the best for us.”5 Sukeforth picked Branca, who then yielded Thomson’s pennant-winning home run.

Two months later, on December 2, Sukeforth married thirty-five-year-old Grethel Winchenbach of Waldoboro, Maine, a widow, who was fifteen years younger than Clyde. They would remain married until Grethel died in 1999. Grethel was Clyde’s second wife. On December 8, 1933, he had married Helen F. Miller of Cincinnati. She died in 1938, about two weeks after the couple’s only child, a daughter Helen, was born.

Sukeforth and the Dodgers parted ways after the 1951 season ended. Many blamed the Branca choice. Sukeforth moved on to the Pittsburgh Pirates, where Rickey had become the executive vice president and general manager. There, as a coach and occasional scout, he played a role in the drafting of Roberto Clemente from the Brooklyn organization in the 1954 Rule 5 draft. Sukeforth recalled the discussion that Pirates executives had before the draft.

“[Branch Rickey asked me,] “Clyde, do you have a candidate?” I said, “Yes sir, Clemente. Any of you fellas seen Clemente? I saw his arm. I sure did, some question in my mind whether it’s better than Furillo’s, but I’ll guarantee you it’s as good, and Furillo had the best arm in the league!”6

Sukeforth retired as a coach at the end of the 1957 season. But he remained in the Pirates organization as a scout and occasional minor-league manager through 1962. He spent the final years of his baseball career as a coach and a scout for the Braves, first in Milwaukee and then in Atlanta.

Sukeforth remained close with many of the players he managed and coached, including Jackie Robinson. Not long before Jackie died in 1972, Clyde saw him for the last time. “I knew Jack wasn’t feeling well,” he recalled, “so when I heard he was being honored by the Virgin Islands at Mama Leone’s restaurant, I figured I’m not going to have many opportunities to see this fellow again. I didn’t expect to have to say anything, I just wanted to see Jack, but they asked me to speak.”7

“I told them I didn’t think my part in Jack’s career was that important. My relationship with Jack was the same as it would have been with any ballplayer, black or white. He sent me a letter a few days later saying he appreciated my modesty, but he thought I was a little more helpful than that. That was kind of him.”8

Sukeforth died at age ninety-nine in Waldoboro, Maine on September 3, 2000. At his request, no services were held. He is buried in Waldoboro, and rather miraculously a fresh baseball can be found on his gravesite at all times.

Among those who remembered Sukeforth fondly was Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s widow. After his passing, Mrs. Robinson recalled in an interview: “I stayed in touch with Mr. Sukeforth through the years. He was very kind to both of us. He was probably one of the most influential people in my husband’s life, especially getting to the big leagues. Mr. Sukeforth cared about Jackie and our entire family. He never forgot us, nor did we ever forget him.”9

Sources

Schultz, Randy, “Clyde Sukeforth: former player, coach and scout played roles in Jackie Robinson’s signing and the 1951 N.L. pennant, Baseball Digest, July 2005.

Anderson, Dave, “Clyde Sukeforth, 98, is Dead; Steered Robinson to Majors,” New York Times, September 6, 2000.

Anderson, Dave, “The Days that Brought the Barrier Down_,” New York Times_, March 30, 1997.

Lindholm, Karl, “The Dodgers Yankee, A Maine Man,” Anderson County Independent, January 15, 2009.

Madden, Bill, “Scout’s Honor,” New York Daily News, July 28, 1996.

Zeigel, Vic, “The SHOT Hits 50, Giants Still Win,” New York Daily News, October 3, 2001.

“Billy Meyer Quits as Pirates Manager,” New York Times, September 28, 1952.

“Georgetown Beats Yale Nine,” New York Times, April 20, 1924.

“Georgetown Nine Win,” New York Times, April 28, 1925.

“Georgetown Wins, 9-4,” New York Times, April 19, 1925.

“Sukeforth’s Eye Improves,” New York Times, December 3, 1931.

“Mike Shatzkin’s Conversation with Clyde Sukeforth,” BaseballLibrary.com (1993 Interview).

“Interview with Clyde Sukeforth,” Maine Memory Network of Southern Maine Center for the Story of Lives, (1998 Interview).

Clyde Sukeforth’s Obituary from TheDeadballEra.com.

Notes

1. “Mike Shatzkin’s Conversation with Clyde Sukeforth,” BaseballLibrary.com, 1993 interview.

2. Randy Schultz, “Clyde Sukeforth: former player, coach and scout played roles in Jackie Robinson’s signing and the 1951 N.L. pennant, Baseball Digest, July 2005.

3. Randy Schultz, “Clyde Sukeforth: former player, coach and scout played roles in Jackie Robinson’s signing and the 1951 N.L. pennant, Baseball Digest, July 2005.

4. Dave Anderson, “Clyde Sukeforth, 98, is Dead; Steered Robinson to Majors,” New York Times, September 6, 2000.

5. Randy Schultz, “Clyde Sukeforth: former player, coach and scout played roles in Jackie Robinson’s signing and the 1951 N.L. pennant, Baseball Digest, July 2005.

6. “Interview with Clyde Sukeforth,” Maine Memory Network of Southern Maine Center for the Story of Lives, 1998 interview, p. 8.

7. Dave Anderson, “The Days That Brought the Barrier Down,” New York Times, March 30, 1997.

8. Dave Anderson, “The Days That Brought the Barrier Down,” New York Times, March 30, 1997.

9. Randy Schultz, “Clyde Sukeforth: former player, coach and scout played roles in Jackie Robinson’s signing and the 1951 N.L. pennant, Baseball Digest, July 2005.