Moose Solters – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

In one sense, Julius Solters began his life in darkness and ended it in darkness as well. He was born of Hungarian immigrant parents and at a very early age worked leading mules in a coal mine near his native Pittsburgh. He ended it without ever seeing his youngest son, Stevie, who had been born after Solters lost his eyesight after being hit by a ball thrown during a pregame practice. He also may never have seen his older brother, John, who stayed behind when his parents came to America.

In one sense, Julius Solters began his life in darkness and ended it in darkness as well. He was born of Hungarian immigrant parents and at a very early age worked leading mules in a coal mine near his native Pittsburgh. He ended it without ever seeing his youngest son, Stevie, who had been born after Solters lost his eyesight after being hit by a ball thrown during a pregame practice. He also may never have seen his older brother, John, who stayed behind when his parents came to America.

His father, Joseph George Soltesz, born in Homrogd, Hungary, worked as a coke puller for Jones & Laughlin, the steel company, in Pittsburgh. The family had to struggle to get by and young Julius worked a number of jobs, among them grocery store clerk, baker’s assistant, steel worker, sheet metal worker, ditch digger, truck driver, and coal miner. He set pins in a bowling alley during grade school. He always loved baseball, too. He was fortunate enough to have grown up near Forbes Field and shagged flies there as a young boy.1

Solters, born as Julius Joseph Soltesz in Pittsburgh on March 22, 1906, told writer Damon Kerby a bit about his early life. “My parents came over from the old country – Hungary. Over there my people knew nothing except to keep their noses in Mother Nature’s soil. When they came to this country, the one dollar or two dollars a day for 12 hours’ work offered by factories and coal mines looked like all the money in the world. The men of my family became laborers.”2

The Soltesz family wasn’t able to earn enough money to bring John over from Hungary, and he grew up there and raised his own family. Joseph and Mary Soltesz had four boys and one girl born in America, but none of them had ever seen their brother John, who was 36 years old at the time of a Sporting News profile on Julius. Nor were his parents able to afford the money to return to Hungary even for just a visit. “When my father and mother got over here, they found out that gold didn’t flow down the gutters of the streets. … The leaving of John behind has been a family tragedy all these years.”3

Julius went to Fifth Avenue High School for two years, but despite playing halfback on the football team, he couldn’t stay interested in school, and figured he was destined to become a laborer as well.

But he enjoyed being around baseball. The Lewis Playground was near his house and he played ball there when he got older. “As a little kid I had served as a water boy for an older boys’ team, and had even shagged flies during morning practice at Forbes Field, where the Pirates play. I took a great shine to Billy Southworth, then with the Pittsburgh club. He was my ideal in every respect. … As I grew older, I began to play sandlot baseball and gradually got into semipro ball around the Western Pennsylvania coal mines, working underground during the week and playing on Sundays.”4 Brothers George, Frank, and Jess all liked playing baseball, too. Julius played some semipro football as well.5

On July, 1, 1927, when Julius was 21, a phone call came in. Julius and his brother Frank happened to be in Dearth, Pennsylvania, playing for the Colonial Mine No. 4 baseball team in the semipro Frick River League. The caller asked “the Solters boy” to report the next day to the Fairmount (West Virginia) Black Diamonds (Middle Atlantic League, Class C). Frank traveled to Fairmount and hit a home run his first time up (off Charles Bender, no less), but then struck out and struck out and struck out. Finally, after an even dozen games, with Solters batting .089 in 45 at-bats, something dawned on manager Joe Phillips. Suspicions raised, Phillips asked him what his name was. “Frank Solters,” came the reply. “It isn’t you I want,” Phillips yelled. “I want your brother Julius. Go home and send him to me.”6

Julius got into 67 games and hit a much more respectable .271, playing outfield as his brother had before him. He was sold to the Columbus Senators of the American Association and hit .250 in 20 at-bats late in 1927. He tried out with the Double-A team in the spring of 1928, but was returned to Fairmount. There, he boosted his batting to .286, with 15 homers, and in 1929 he hit .294 with 21 homers. Solters still hadn’t cracked .300 but he was progressing each year and when he said he wouldn’t return for a fourth year, Fairmount sold his contract to the Baltimore Orioles in the Double-A International League.7 He played in 76 games and hit .312, a good number of those games as a pinch-hitter. He made nine errors in 52 games in the outfield, and was asked to move a couple of levels down and spend 1931 with Chattanooga of the Southern Association, but he suffered a charley horse early in spring training and never got to play in a regular-season game for the Lookouts.

After Solters healed, he spent the year with the Shreveport Sports (Single A, Texas League) working on his fielding. His hitting dropped off to .241, but he improved at least a bit in the field. Shreveport didn’t really want him back, however, and he was sent to the Eastern League to play for the Albany Senators. He didn’t turn up when expected, and a couple of newspaper articles reported him as “missing” – but he did arrive on April 15, 1932, the last player to report. With Albany, in 71 games, he was hitting .304 and leading the league with 76 RBIs, when the Eastern League went bust, disbanding on July 17.

Solters was sent to Class B to play for the Binghamton Triplets of the New York-Pennsylvania League, where he upped his hitting in the lower level league, batting .393 and knocking in 40 runs in 39 games.8

In 1933, back in Double-A, Solters got a good chance to show himself on a regular basis, when Baltimore player/manager Frank McGowan was hurt early in the season. Julius played in 147 games, batting a league-leading .363 with 36 home runs. There was one game in Rochester when he homered twice in the same inning. His 46 doubles led the league, and so did his 157 runs batted in. Not surprisingly, Solters was named to the league All-Star team.

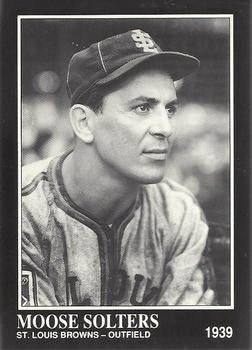

By this time, the 6-foot, 190-pound, solidly built Solters had acquired the nickname Moose – bestowed upon him by Albany manager Bill McCorry. It was one of a few nicknames he had over time, including Tarzan, Salty, Peanuts, Greek, Turk, and even Zbyszko (presumably after the noted 1920s wrestler and strongman Stanislaw Jan “Zbyszko” Cyganiewicz). The most curious nickname was an early one that stuck with Solters for a remarkably long time: Lemons. He told Boston sportswriter Burt Whitman about the origin: “When I was a little bit of a shaver in Pittsburgh, I always hung around the ballparks when the older kids were playing. They had a great habit, on hot days, of getting lemons and sucking on them for refreshment. And I used to make myself solid with the big kids by getting lemons and handing them around to the good players. When they felt dry and wanted a lemon, they’d holler for me and my name, of course, was ‘Lemons,’ and it still sticks, all through the International League, too, last year.”9

Younger brother Jess played a bit of baseball, too, first for Mount Airy in the 1934 Bi-State League, then sold to Fort Worth. He seems to have played 10 games for the El Dorado Lions in the 1935 East Dixie League. Brother George (and Frank, back home after his brief stint with Fairmount) played semipro ball.10

The Boston Red Sox secured the rights to Moose’s contract for 1934, as new owner Tom Yawkey and general manager Eddie Collins began to spend money to sign up good players. Word was that Yawkey had forked out 20,000to20,000 to 20,000to50,000 (reported figures differ) to Baltimore in early September 1933 to get Solters, outbidding a number of other teams. He was, wrote The Sporting News, “one of the best batting prospects to be developed in the International in some time.”11

Red Sox manager Bucky Harris saw him as a key man for the coming season. Scribes saw Solters and Dusty Cooke as certainties for outfield berths; Julius had primarily played center field for Baltimore but expressed no preference for one position or another. He was so confident in his ability to play major-league baseball that he reportedly signed a blank contract. Eddie Collins said, “Solters declared that he was satisfied to let the Boston club fix his salary in accordance with what we thought he was worth after we have seen him win a regular place on the team. This is the kind of confidence that makes young fellows succeed in the big leagues.”12 With Baltimore, he’d been making 150amonth,or150 a month, or 150amonth,or900 if he played the full season.

Solters got off to a good start with the Red Sox, his first big game coming on May 6, when he helped Boston set a major-league record by scoring 12 times in an inning, the bottom of the fourth in a game against the Tigers. Solters tripled and drove in a run his first time up, and singled and drove in another run the next time he came up to bat. He scored both times, and drove in another run later in the game. Just a couple of weeks later, though, on May 23, a pitch by the Cleveland Indians’ Mel Harder broke a bone in Solters’ left hand. He was hitting .326 at the time. He didn’t come back for a month.

When he did, he pretty much picked up where he left off, but saw his average dip to .299 by season’s end. He’d played in 101 games. After the 1934 season, Julius married Amy O’Halek, who’d grown up in the same neighborhood in Pittsburgh.

Solters was struggling in his sophomore year, hitting .241 after his first 24 games, when he was traded to the St. Louis Browns. New Boston manager Joe Cronin felt he needed an infielder more and wanted Ski Melillo to play second base. On May 27, while the Browns were in Boston, the Red Sox gave St. Louis some money and Moose to get Melillo. “We hate to part with Melillo,” Browns manager Rogers Hornsby said. “But we are in greater need of a power hitter. The Moose gives us that.”13

Solters switched uniforms that same day – and also saw his wife get hit in the face by a ball off the bat of his former outfield teammate, Dusty Cooke. She was not seriously injured. (Six years later, it was Solters himself who was hit by a ball thrown by a teammate, and it caused permanent damage to his optic nerves.) On the day of the trade, Solters had a hard time fitting – literally – into Melillo’s old uniform, but Hornsby promised he’d get him a new uniform when the team got back to St. Louis.14

Solters played in 127 games and hit .330 for the Browns; all 18 of his homers that year were for St. Louis – three in one game, on July 7. Between the two teams, he accumulated 201 base hits. And in the 10 games he played against the Red Sox, he hit .370 with 10 RBIs. It was Cronin, though, who had set Solters on the right path, changing his batting stance. Solters used to face the pitcher directly, twitch around considerably while awaiting the pitch, and not stand deep in the batter’s box. He explained why he faced the pitcher: “I can watch the pitcher with both eyes. My nose does not get in the way of one of my eyes.”15 The new approach did pay off. Or maybe it was the food. He told Burt Whitman that the first thing manager Hornsby told him was to eat plenty of meat and potatoes: “You can’t clout them on salads or ice cream sodas.”16

In 1936, Solters cooled off to .291 but he was very productive with a career-high 134 RBIs. He ranked fifth in the league in RBIs two years in a row. That fall, he and Amy purchased a 25-acre farm near Valencia, Pennsylvania, north of Pittsburgh, where, he said, he planned to become a poultry farmer.

Because of his success, Solters was trade bait. There were rumors the Red Sox were going to make a move to bring him back. Paul Shannon of the Boston Post wrote that Tom Yawkey “has never ceased to regret the transaction that sent Solters to the Browns.”17 Come January 17, 1937, however, the Browns sent Solters, pitcher Ivy Andrews, and infielder Lyn Lary to Cleveland for pitcher Oral Hildebrand, infielder Bill Knickerbocker, and outfielder Joe Vosmik. Solters performed well for the Indians, hitting .323 and driving in 109 runs with a career-best 20 homers. The next season, 1938, was rough, though. Solters was a holdout in the spring, then got into only 67 games. His average plunged to a dismal .201, and his work in the field was “erratic.”18 Everyone assumed Solters was due to be traded away, but Cleveland general manager Cy Slapnicka just called it a “bad year” and planned to keep him.

Solters had played well under manager Steve O’Neill in 1937, but new skipper Ossie Vitt was another story altogether in 1938. For whatever reason, perhaps his holdout, Vitt played Solters rather little. He went into a prolonged slump and by that time, Vitt couldn’t in all fairness to the team keep sending him out there day after day. He benched Solters. Moose recovered some in 1939, and was hitting .275 after his first 41 games. He was put on waivers and claimed by his old team, the Browns, for the $7,500 waiver price. For the Browns, he hit only .206 in 40 games, and in December they traded him to the White Sox for outfielder Rip Radcliff.

Moose enjoyed a good 1940 season for Chicago, batting .308 with 80 RBIs in 116 games, but 1941 saw a dropoff. Before spring training began, he and two other “fat men” spent a compulsory week in Hot Springs, Arkansas, taking off the lard before the team opened spring training in Pasadena, California. It apparently didn’t help; Solters’ batting average dropped off to .259. He suffered a blow to the head during fielding practice before the August 1 game at Griffith Stadium in Washington. “I was crossing the field, heading for the dugout, when I saw my two brothers-in-law in the stands. I waved to them and that’s all I remembered,” he said later.19 Hit squarely in the left temple by a ball thrown by teammate Joe Kuhel to Luke Appling, Solters was knocked unconscious, with a fractured skull. Put on waivers after the season, he was unclaimed. He was released to St. Paul on December 9, two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The following April, instead of reporting to St. Paul and accepting a pay cut from 10,000to10,000 to 10,000to2,750, Solters retired. He opened a tavern in Pittsburgh.

Julius came back for another try with the White Sox in 1943, turning up in spring training (held that year in French Lick, Indiana, due to wartime travel limitations) and got into 42 games but suffered terrible headaches and some double vision. He batted just .155, with 15 hits in 97 at-bats. (His only extra-base hit was a home run.) Solters played through the end of the season, and his contract was sold to the Milwaukee Brewers in December but he couldn’t keep on playing and retired for good. He was 39 years old. “I knew my eyes were going when I could only see half of Tiny Bonham, the Yankee pitcher, and you know how big he was,” Solters told UPI. It was a slow deterioration over a period of a few years. At first he tried to keep it from Amy and their children, but it became progressively worse. He was tested at a number of facilities in different states, but the loss of vision was irreversible.

The major-league players’ pension plan had come into play, but Solters had stopped playing before the period of eligibility. “Rules are rules,” he shrugged. “And I was out of the game before I was eligible for benefits.” A small monthly check from the Association of Professional Ballplayers of America helped him over some rough spots.20 He kept the tavern going and their five children worked their way through college. But he never saw his youngest child, Stevie. He’d gone completely blind by the time Stevie was born.

Sports editor Les Biederman of the Pittsburgh Press took up Solters’ cause. Julius hadn’t complained and was in fact president of the Pittsburgh Professional Ballplayers of America when the two met at a dance held by the organization. Biederman wrote to C.C. Johnson Spink of The Sporting News, soliciting the national newspaper’s help, telling of how Solters, though completely blind, had led his wife, Amy, onto the floor for a dance. “When they came out onto the floor, everybody else stopped and applauded. Women wept. It was the most beautiful and saddest sight I’d ever seen.”21

Amy Solters was a blessing, and the children did their part; from the age of 12, son Joe was often seen escorting his father to ballgames in Pittsburgh. Julius always paid their way in until a reporter wrote a story about it in late 1949. Amy talked about Moose’s spirit (she called him Moose), and how she found it difficult to explain to Joe why he and his dad had to pay to go to ballgames. “I simply tell him there are many things in life you don’t ask for. That you should work hard all the time and that being injured, crippled, or blind is no excuse for not working. Moose today is a greater inspiration to youngsters (and) to fans than he ever was when he was a big, healthy baseball hero.”22 The family wasn’t destitute. The American League looked into Solters’ circumstances and determined that he was not indigent. Both leagues responded to Biederman’s appeal by presenting him a lifetime pass.

Moose endured blindness for more than three decades, but suffered a stroke in February 1970 that debilitated him and forced him to redevelop his ability to speak. He’d learned Braille and read many books provided by the Library of Congress, and even helped host benefits to help others stricken with blindness. Five and a half years after his stroke, on September 28, 1975, he died in Pittsburgh.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the text, and the Solters player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, the author used the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Boston Evening Transcript, August 8, 1935.

2 Unattributed August 7, 1935 clipping written by Damon Kerby, from Moose Solters player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

3 The Sporting News, January 3, 1935.

4 Kerby, August 7, 1935 clipping, Solters Hall of Fame player file.

5 Christian Science Monitor, August 31, 1934.

6 Dick Farrington, The Sporting News, January 3, 1935; Henry P. Edwards, American League Service Bureau press release, December 22, 1935.

7 Boston Herald, March 12, 1934.

8 The Sporting News, December 22, 1932. The story reported that Solters was “said to be of Indian descent.”

9 Undated article from the Solters player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

10 The Sporting News, January 3, 1935.

11 The Sporting News, September 14, 1933.

12 Unattributed February 6, 1934 clipping, Solters Hall of Fame player file.

13 Undated 1941 Sam Greene article, Solters Hall of Fame player file.

14 Boston Traveler, July 24, 1935.

15 Boston Herald, March 6, 1935.

16 Boston Traveler, July 24, 1935.

17 The Sporting News, January 7, 1937.

18 Unattributed August 3, 1939 clipping, Solters Hall of Fame player file.

19 Washington Post, April 21, 1970.

20 Unattributed October 18, 1975 article, Solters Hall of Fame player file.

21 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 10, 1967.

22 Unattributed 1949 newspaper clipping, Solters Hall of Fame player file.