Sparky Anderson – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

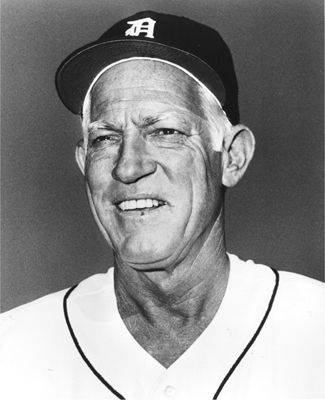

George Lee “Sparky” Anderson was one of the great baseball men of all time in terms of success, integrity, and personality. He led the Cincinnati Reds to back-to-back championships in 1975 and 1976, and the Detroit Tigers to a World Series title in 1984, becoming the first manager to win the World Series in both leagues. Four times in his career, teams he managed won more than 100 games, and in six other seasons his teams won at least 90 games. In his 26 years managing in the majors Anderson amassed 2,194 victories, five pennants, and three World Series championships.

George Lee “Sparky” Anderson was one of the great baseball men of all time in terms of success, integrity, and personality. He led the Cincinnati Reds to back-to-back championships in 1975 and 1976, and the Detroit Tigers to a World Series title in 1984, becoming the first manager to win the World Series in both leagues. Four times in his career, teams he managed won more than 100 games, and in six other seasons his teams won at least 90 games. In his 26 years managing in the majors Anderson amassed 2,194 victories, five pennants, and three World Series championships.

Born in Bridgewater, South Dakota, on February 22, 1934, to LeRoy and Shirley Anderson, George relocated with his family in 1942 to Southern California, where his father and grandparents found wartime work in the shipyards. LeRoy played some semipro baseball and passed his love of the game on his son. Young George became a batboy for the University of Southern California’s Trojans baseball team, coached by Raoul “Rod” Dedeaux, an early influence in Anderson’s baseball life.

During his childhood Anderson played a lot of sandlot ball. In 1951 his American Legion team won a national championship at Briggs Stadium in Detroit (later renamed Tiger Stadium), the place where Anderson later managed the Tigers. His Dorsey High School team won 42 consecutive games, and Anderson was named an all-city player in his junior and senior years. Despite passing up a school closer to home and having to take two buses to get to Dorsey, Anderson chose it for its baseball program.

While still in high school, Anderson worked a summer job loading lumber on boxcars. In the evenings he played with a semipro team. He graduated from Dorsey High in 1953 and Dedeaux offered him a partial baseball scholarship to USC. Anderson never went to college, though, because a Brooklyn Dodgers scout he had met years earlier on the sandlots, Lefty Phillips, offered him $250 a month to play for the Dodgers’ Santa Barbara team in the Class C California League. Anderson’s parents knew and trusted Lefty, who by the time Anderson graduated from high school had moved up from sandlot scouting to scouting for the Dodgers. Anderson called Lefty “the sharpest baseball man I ever met.”

Phillips knew Anderson’s limitations and told him that to make it in baseball he would have to work very hard. Anderson was only 5-feet-9 and weighed just 170 pounds, but his determination and will to win gave him an edge. Anderson’s boyhood friend Billy Consolo signed his first major-league contract that same year, with the Boston Red Sox. Consolo was one of baseball’s bonus babies, with the rule at the time requiring the team providing the bonus to keep him on its major-league roster for two seasons. Anderson’s signing gave him a steady income, even if it wasn’t as a bonus baby, and he bought an engagement ring for his childhood sweetheart, Carol Valle. The two had known each other since the fifth grade and began dating in high school. They married in October 1953, at the end of Anderson’s first minor-league season as shortstop for the Santa Barbara Dodgers. He played in 141 games and hit for a .263 average.

The playing manager at Santa Barbara was George Scherger, a man Anderson would later invite to coach for him in Cincinnati. Anderson described Scherger as a man who wanted to win badly. Whenever the team lost, there would be extra practice the next day. This drive influenced Anderson, who adopted it when he became a manager himself.

Anderson moved around in the Brooklyn minor-league system, playing in Pueblo, Colorado, Fort Worth, Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League, and Montreal in the International League. In Pueblo he hit .296 in 1954. In 1955 he moved up to Double A with the Texas League’s Fort Worth Cats. Tommy Holmes was the manager. (The team produced several future big-league managers. Anderson; Dick Williams, who was Anderson’s opposing manager in the 1972 and 1984 World Series, managed in the majors for 21 seasons, and joined Anderson in the Hall of Fame in 2008; Danny Ozark, who managed the Philadelphia Phillies and San Francisco Giants; Norm Sherry, who managed the California Angels and coached on several major-league teams; and Maury Wills, who managed two years in Seattle.)

Anderson received his nickname in Fort Worth. A radio announcer dubbed him Sparky because of his feistiness. It was a trait that sometimes got him into trouble. He wanted to win so badly that he could not tolerate anything that got in the way.

In 1958 the Dodgers put Anderson on their 40-man roster. He later remembered, “I had no right to think I could break in with a club that had [Gil] Hodges, [Charlie] Neal, Don Zimmer, Junior Gilliam, Dick Gray, [Carl] Furillo, Duke Snider, Gino Cimoli, Norm Larker, and Johnny Roseboro — and with a pitching staff built around Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, and Johnny Podres. I simply didn’t belong in that kind of company.” Sparky was sent back down to Montreal. Dodgers Manager Walter Alston broke the news of his demotion to him at a time when most managers left this duty to the traveling secretary. This impressed Sparky, who as a manager followed that example. He was told that the Philadelphia Phillies had expressed an interest in him, and since they had an International League farm team in Miami, they would be able to get a look at him.

In 1958 the Dodgers put Anderson on their 40-man roster. He later remembered, “I had no right to think I could break in with a club that had [Gil] Hodges, [Charlie] Neal, Don Zimmer, Junior Gilliam, Dick Gray, [Carl] Furillo, Duke Snider, Gino Cimoli, Norm Larker, and Johnny Roseboro — and with a pitching staff built around Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, and Johnny Podres. I simply didn’t belong in that kind of company.” Sparky was sent back down to Montreal. Dodgers Manager Walter Alston broke the news of his demotion to him at a time when most managers left this duty to the traveling secretary. This impressed Sparky, who as a manager followed that example. He was told that the Philadelphia Phillies had expressed an interest in him, and since they had an International League farm team in Miami, they would be able to get a look at him.

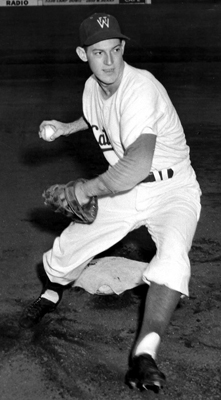

Sparky played reasonably well in Montreal, batting .269 and stealing 21 bases for the Royals. He even hit two home runs. (“That’s what’s so good about not hitting many. You remember them all,” he said.) He was named the club’s most valuable player and finished second in the running for the league MVP. He did indeed catch the eye of the Phillies, who traded for him and made him their starting second baseman.

Sparky’s first day in the big leagues came on Opening Day of 1959 against Cincinnati at Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium. In the eighth inning, he singled home what became the winning run in a 2-1 game. He received his first media barrage afterward. In his autobiography The Main Spark, he wrote that there was no more media attention for him until August that year. He played in 152 games, but batted only .218 and drove in only 34 runs. It was to be the only year he played in the big leagues.

That year he noticed a difference in the routine compared with the Dodgers’ big-league spring camp. The Dodgers operated on a set schedule, discipline that Sparky would come to value. In Philadelphia no one kept track of when players rolled in for practice, and often there would be no coaches around, according to Sparky’s account. The Phillies that year were a last-place team, as they had been the year before. Sparky said he would never forget the thunderous boos the hometown crowd greeted the Phillies with as they took the field on Opening Day. There was definitely not an attitude of winning in Philadelphia, and Sparky had been raised in an organization with the opposite outlook.

Sparky later said, “I realized you can’t be in a game as a professional unless winning and losing are everything, your whole life.”

During 1960s spring training, when he didn’t make it into many games, Sparky knew he would not stay with the team. He had hoped he would be traded to another major-league team, but instead was sold to Toronto. With one child and another on the way, Sparky was about to quit. Toronto’s owner, Jack Kent Cooke, offered him 10,000toplay,10,000 to play, 10,000toplay,2,000 more than he had made in Philadelphia. Because he had bills to pay, he accepted. Cooke told him he planned to sell him to a major-league club, but Sparky did not believe it would happen. He called the 1960 season a turning point in his career. He decided to start observing baseball strategies with the idea of one day becoming a manager. After four more years in the minors, all with the Maple Leafs, he landed his first managerial job, in Toronto in 1964. He uttered what would be the beginning of many boasts that he would later regret by saying, “If I can’t win with this club, I ought to be fired.”

Anderson’s temper made him a prophet. He was fired at the end of the season and soon realized that jobs for managers who could not control their emotions during the games were few. By his own admission, he was lucky to get his next job, with the St. Louis Cardinals’ farm club in Rock Hill, South Carolina, in 1965 because the Cardinals were desperate to find a manager just before spring training. Bob Howsam was the Cardinals’ general manager; the association proved to be advantageous a few years later. In 1968, when Howsam was the GM of the Cincinnati Reds, Sparky was hired to manage the Reds’ minor-league club in Asheville, North Carolina.

Anderson could not make ends meet during his minor-league managing career, so he took various odd jobs, including a factory job, a stocking job at Sears, and some offseason gigs selling used cars.

Then, after five years as a minor-league manager, Anderson landed a major-league coaching job with the San Diego Padres in 1969. At the end of the season he resigned to accept a job coaching with the California Angels under his old mentor Lefty Phillips. But he never took that job.

While the ink was still drying on Anderson’s contact with the Angels, California general manager Dick Walsh received a phone call from Bob Howsam, the Reds’ GM, requesting permission to speak with Sparky about managing in Cincinnati. It was Walsh who broke the news to Sparky.

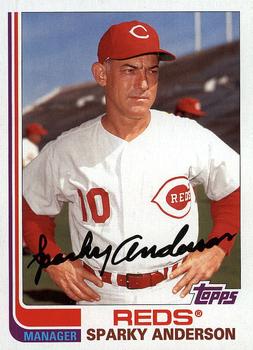

Sparky’s hiring prompted Cincinnati newspapers to declare: “Sparky Who?” He was only 35 years old and unknown to the public.

One of Anderson’s first moves as Reds manager was to make Pete Rose the team’s captain. Because Willie Mays was so well received in San Francisco as the Giants’ captain, Anderson thought Rose could serve the same role in Cincinnati. Rose was very popular, a hometown boy, and the top player on the team. With Rose delivering the lineup to the umpire before the game, perhaps people would not focus on “Sparky Who?”

Anderson inherited a talented team and remarked to his coach, George Scherger, that it would win the division by 10 games. These types of statements were often seen as exaggerations, and Sparky himself admitted that he was overconfident, but the fact remained that the 1970 Reds were an excellent team. Catcher Johnny Bench was on the verge of a breakout career season. Tommy Helms, Lee May, Tony Perez, Bernie Carbo, and Bobby Tolan joined Rose on that team. The Reds had finished in third place in 1969, winning 89 games, and they were primed to be winners. The 1970 team brought in rookie shortstop Dave Concepcion and pitchers Don Gullett and Pedro Borbon. In July of that year the team moved from aging Crosley Field into the new Riverfront Stadium and began to play on artificial turf.

Anderson inherited a talented team and remarked to his coach, George Scherger, that it would win the division by 10 games. These types of statements were often seen as exaggerations, and Sparky himself admitted that he was overconfident, but the fact remained that the 1970 Reds were an excellent team. Catcher Johnny Bench was on the verge of a breakout career season. Tommy Helms, Lee May, Tony Perez, Bernie Carbo, and Bobby Tolan joined Rose on that team. The Reds had finished in third place in 1969, winning 89 games, and they were primed to be winners. The 1970 team brought in rookie shortstop Dave Concepcion and pitchers Don Gullett and Pedro Borbon. In July of that year the team moved from aging Crosley Field into the new Riverfront Stadium and began to play on artificial turf.

The Reds won 102 games in Anderson’s major-league managerial debut season, a record that gave them the National League West Division championship over the Los Angeles Dodgers by 14½ games. The Reds swept the Pittsburgh Pirates in the best-of-five National League Championship Series to take the pennant and meet the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. The Reds fell to the Orioles in five games, but it was a stunning first year for Anderson.

Anderson brought his work ethic with him to Cincinnati, and some players called his spring training a “slave camp.” GM Howsam insisted on a clean-cut look for the team: no facial hair, no long hair, and suit jackets for traveling, which Anderson supported and enforced. He believed that mannerisms and dress carried over into a kind of self-discipline that helped his players work together as a team.

But probably more central to Sparky’s success as a manager was the way he cared about his players. He allowed them to question him, and even encouraged it. He said, “I know there are managers who would never allow themselves to be put on this level with their own ballplayers, but as far as I’m concerned, it’s a form of communication.”

The following season was not a good one; the Reds finished below .500 and in fifth place. The following offseason brought the “Big Deal.” The Reds traded Lee May, Tommy Helms, and utility man Jimmy Stewart to the Houston Astros for Joe Morgan, Denis Menke, Jack Billingham, Cesar Geronimo, and Ed Armbrister. Cincinnati made the trade to gain speed at first and third base, essential for playing on Astroturf.

Besides being known as Sparky, Anderson was called Captain Hook because he never hesitated to pull a pitcher out of the game. The Big Red Machine was not blessed with superior starting pitching, and in an age when complete games were still common, Anderson’s tendency to replace pitchers during a game drew notice. He said, however, that he could always sense when a pitcher was just about to lose his effectiveness. His players realized that while he cared for players as individuals, he would not cater to one man. Second baseman Joe Morgan said, “In his passion for winning, he will not ever put the feelings of any individual above the team.”

The Reds returned as pennant winners in 1972 and faced the Pirates again. This time the NLCS went five games with the Reds coming out on top. The finish was so exciting that before the World Series against the Oakland A’s, Anderson made a statement he later regretted. He told the press that the two best teams in baseball had already played a series (Cincinnati and Pittsburgh) and that the World Series would be anticlimactic. Although he said what he really thought, the statement fired up the Oakland team. After the Reds lost the first two games, Anderson realized how much he had underestimated his opponents. The Reds lost to Oakland in seven games, but the Big Red Machine was building momentum.

In 1973 the Reds again won their division, but lost to the New York Mets in the League Championship Series, three games to two. In 1974, the Reds finished second behind the Los Angeles Dodgers, despite winning 98 games.

The Reds teams of 1975 and ’76 secured the label of dynasty and have been considered two of the best of all time. In 1975 they took first place early in June and never relinquished it. Pitcher Don Gullett was on his way to a remarkable season when he fractured his thumb. Without their star pitcher, the rest of the staff had to pick up the slack. Because the Reds’ bullpen was strong, the Captain Hook strategy was key. And with hitters like Morgan, Rose, George Foster, and Ken Griffey Sr. batting over .300 and Bench and Perez driving in more than 100 runs, the Big Red Machine usually outscored their opponents anyway. The Reds finished the season 20 games ahead of the second-place Dodgers with 108 wins, and swept Pittsburgh in the NLCS.

The 1975 World Series has gone down as one of the greatest ever. As the Series opened, Sparky began feeling the pressure. He was more cautious this time about feeling overconfident. The Boston Red Sox were the American League champs after sweeping the Oakland A’s in the ALCS. The opening game was an eye-opener for the Big Red Machine when they faced the pitching mastery of Luis Tiant and lost 6-0. After winning the next game in a tight match, the Reds won Game Three in extra innings. Tiant pitched the Red Sox to another victory in Game Four, but the Reds came back to win Game Five. When the Series returned to Boston, rain delayed play for 72 hours. Game Six, however, proved to be worth waiting for — the game that many, including Sparky himself, say was the single best game in World Series history.

Captain Hook pulled pitcher Gary Nolan after two innings, trailing 3-0. The Reds got to Tiant this time and evened the score in the fifth. By the eighth inning, leading 6-3, the Reds were thinking the championship was in the bag. After Pedro Borbon put two runners on, he got the hook and was replaced by Rawly Eastwick, who got two batters out. Then Bernie Carbo, a former Red, came in to pinch-hit. Carbo had already had a pinch homer in the Series, and Sparky didn’t figure he had another in him. But on a 2-2 count, Carbo drove the ball over the center-field wall to tie the game. After the Reds were retired in order in the ninth, the Red Sox loaded the bases with nobody out — but were unable to score. In the 10th inning, Red Sox outfielder Dwight Evans made a spectacular catch on a line drive by Morgan, robbing him of a possible home run and then doubling up Griffey off first base. The Reds threatened in the 12th, but didn’t score. In the bottom of the 12th, Pat Darcy, the Reds’ eighth pitcher in the game, came in to face catcher Carlton Fisk, who hit a high fly ball to deep left field. As Fisk ran to first base, he — and everyone else in the park — wondered if the ball would stay fair. Fisk jumped up and down waving his arms toward fair territory in what has become an iconic image. It was a homer, barely, hitting the foul pole. The Red Sox won, sending the Series to a deciding Game Seven. Sparky later said, “How can a manager of a losing team call it the greatest game ever played? Well, winning or losing, a man can’t lie to himself.”

Game Seven was a come-from-behind affair with the Reds finally coming out on top, 4-3, and winning their first world championship under Anderson. Sparky was unprepared for the media blitz that continued to follow him into the next season and the expectation of winning another championship, but he soon learned to make the media his friend and to encourage his players to do so also. Pete Rose said, “He didn’t make an enemy out of the press. He used it. And he taught us how to use it.” Later, Lance Parrish echoed this sentiment in Detroit: “Sparky let us know it wasn’t fair to treat the media any differently that we would treat anyone else. They had a job to do.”

Pete Rose and Joe Morgan led the league in several offensive categories in 1976, and while the Reds had no big winning pitchers, they did have seven pitchers who won at least 11 games each. After their 102-win regular season, the Reds did not lose a postseason game, sweeping the Philadelphia Phillies and then the New York Yankees in the World Series.

During that World Series, a reporter asked Anderson to compare his catcher to Yankees backstop Thurman Munson. Sparky said, “Don’t ever embarrass nobody by comparing him to Johnny Bench.” Sparky meant it as a general statement. When he returned home to California, he wrote Munson a letter of apology.

In 1977 the Reds finished second behind the Dodgers, and although 1978 was a better year, they finished second again. The Big Red Machine was being dismantled. Bob Howsam retired after the season. Winning was expected in Cincinnati, and Anderson was fired late that year. He was upset about how it happened. The Reds had just finished a tour in Japan, and management did not want to fire Sparky before that had been completed. But it was late, and most major-league clubs had already chosen their managers for the coming season. The firing was unpopular with the fans in Cincinnati and with the players. Joe Morgan said, “Sparky’s firing was wrong and to this day, I don’t understand it.” It was a blow that Sparky didn’t see coming.

Anderson was about to sign a long-term contract to manage the Chicago Cubs in 1979 when Detroit Tigers general manager Jim Campbell got wind of the deal. He contacted Sparky, who realized that the team was filled with young players. Anderson had enjoyed mentoring young players in his minor-league days.

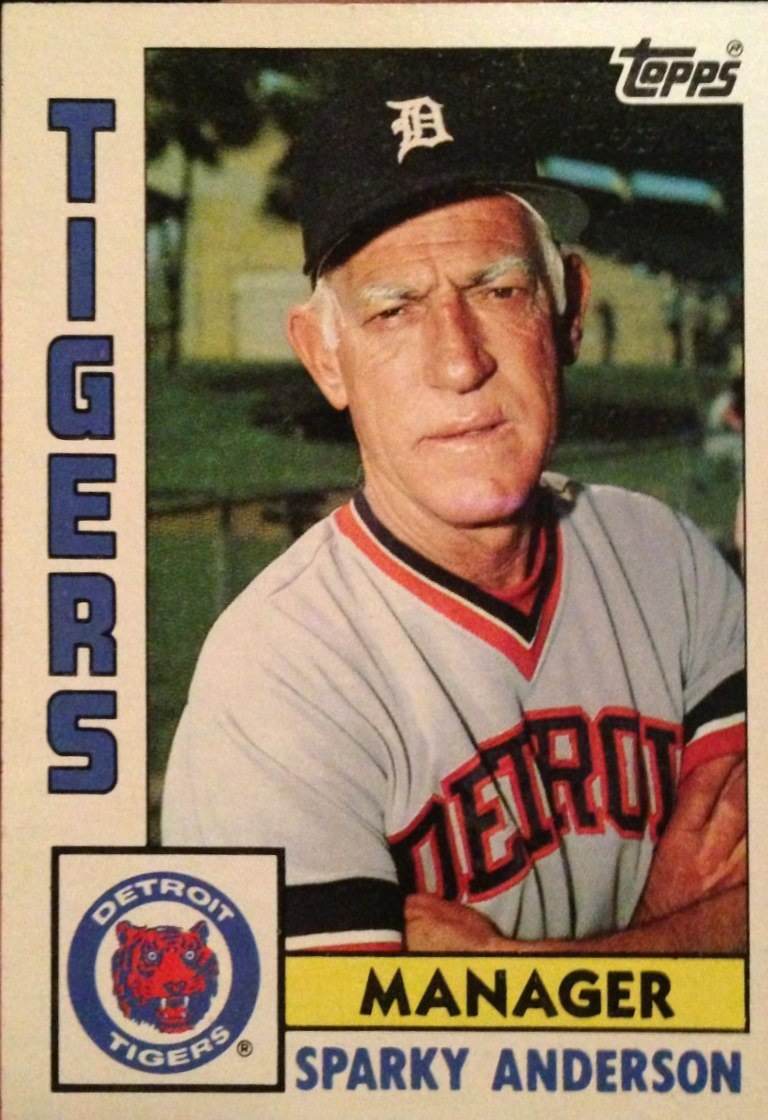

At the press conference announcing his hiring, Anderson made another of his infamous predictions, saying the team would win a world championship in five years.

With talent like Alan Trammell, Lou Whitaker, Kirk Gibson, Lance Parrish, Jack Morris, and Dan Petry, Sparky was confident. He also realized that discipline and conduct as a professional would have to be taught. Kirk Gibson later said, “He wanted me to learn the game of baseball and learn how to treat people right. It took four to five years to get through to me.”

As he did in Cincinnati, Anderson kept an open-door policy. Players were encouraged to speak their minds, but Sparky had the final say. He called the team “rougher than a three-day beard.” He started with fundamentals, drilling the players until their skills became routine. He insisted on coats and ties for traveling, saying, “If you carry yourself proudly, you look like a pro.”

In 1981 the Tigers surprised the American League by making an East Division pennant run during the second half of the strike-split season. In 1983 the team began to show its potential by winning 92 games. The next season was magical.

The 1984 Tigers led their division wire to wire, starting off by winning nine straight games, and then going an unbelievable 35-5 to leave their opponents in the dust in what became a 104-win season. What Sparky had in Detroit, which he had never had in Cincinnati, was two superior starting pitchers to lead his rotation, Jack Morris, who pitched a no-hitter in April, and Dan Petry. Reliever Guillermo Hernandez, acquired in a trade in March, was an All-Star while winning the American League Cy Young and Most Valuable Player Awards.

But pitching was not the team’s only strength. Trammell led the team in batting with a .314 average. Parrish was an All-Star that year, won the second of three straight Gold Gloves, and hit 33 home runs.

When the team clinched the division championship, Anderson felt vindicated. He remembered thinking, “No one will ever question me again.” No matter what happened in the postseason, the best team, he said, was the one that had won 104 games in the regular season and wore a big “D” on its uniforms.

The Tigers swept the Kansas City Royals in the AL Championship Series. Sparky took a team to the World Series for the fifth time in his career, this time against a National League club, the San Diego Padres. The first game was close, with Detroit winning, 3-2. After the game, Lou Whitaker complimented his manager: “When Sparky came to us from Cincinnati, he brought us back to fundamentals. We had a lot to learn and it’s paying off.” The Tigers lost Game Two, but that was the only game they would lose, and they became world champions before the hometown crowd.

After the Series, Sparky’s wife wanted him to quit. He thought about it. It had been a tough year. He was proud of the team and happy for the city of Detroit, but for five years he had struggled with trying to prove Cincinnati wrong for firing him, and with the success of Detroit that year, the pressure he put on himself became almost unbearable. He had to get back to the business of baseball and to enjoying the game again. He couldn’t do that if he quit.

There would be no back-to-back championships for Anderson in Detroit. In 1985 and again in 1986 the team finished third. The 1987 Tigers were not expected to do much better and early in May were in last place. Anderson chose that time to make another prediction, saying his team would be in the race by the end of the season. The Tigers started putting together some win streaks. Before a season-ending series in Detroit against the Toronto Blue Jays, the Tigers were one game behind Toronto. Detroit finished with a flourish, winning three straight one-run games to clinch the AL East title, although the Tigers lost to Minnesota in five games in a best-of-seven ALCS.

The team that year had no outstanding talent save for Alan Trammell, who finished second in the voting for Most Valuable Player. Anderson said, “We had no business running with the big boys. It was pure determination.” Pitcher Jack Morris said, “In 1984, we probably had the best club I ever played on in Detroit. In ’87 we were less talented but typical overachievers. We didn’t realize we weren’t that good.”

Sparky’s efforts with the team that year won him the American League Manager of the Year award. He said, “When I look back on that year, I still feel a high. The guys on that team can be proud of themselves for the rest of their lives.”

In 1988 the team finished second behind the Red Sox, but 1989 saw the Tigers lose 103 games. For a man who wanted to win more than anything else, it was a horrible year. Anderson was also experiencing personal problems as his daughter was undergoing a painful divorce in California and he felt guilty about his own absence from the family.

In 1988 the team finished second behind the Red Sox, but 1989 saw the Tigers lose 103 games. For a man who wanted to win more than anything else, it was a horrible year. Anderson was also experiencing personal problems as his daughter was undergoing a painful divorce in California and he felt guilty about his own absence from the family.

Anderson, who believed that because baseball had blessed him he had a responsibility to give back to the community, was always participating in charity events. In May of that year he attended an event at Children’s Hospital and afterward grew so fatigued that Tigers president Jim Campbell sent him home to California to rest. When Sparky left Detroit, he believed he wouldn’t manage again. He blamed himself for Detroit’s terrible year, but with the team he had and the injuries they suffered, even Sparky Anderson could not coax a winner. He was finally able to give up his obsession for winning after spending 17 days away from the team. He said, “My greatest gift today is knowing I have a tomorrow.”

Anderson continued to manage mediocre teams in Detroit through 1995. That season, during spring training, he drew a lot of attention for refusing to manage replacement players during a player strike. But he said later that that was not the whole story. He knew that management would never open the season with replacement players; it was a ruse. “I managed 25 years at that time in the major leagues, and I was no joke. I wasn’t going to be part of a joke. That was the biggest travesty I have ever seen in my career.”

Sparky was granted a leave of absence and returned to manage that year when, as he predicted, the strike was settled and replacement players were dismissed. While rumor said he was forced out of the game, Anderson had been considering retiring for some time. He left as one of baseball’s winningest managers, fifth all-time as of 2010. He was the first manager to win the World Series in both leagues. In 1984 and 1987 he won the American League Manager of the Year award. He was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2000.

Anderson’s return visits to Detroit were not all that frequent in retirement. He stayed away from the final game at Tiger Stadium in 1999. But he turned up in uniform at the Tigers’ spring training home in Lakeland in 2003 to give support to new Detroit manager Alan Trammell, one of his protégés. Sparky also showed up at the 25th anniversary gathering of the 1984 Tigers championship team in Comerica Park in Detroit. Tigers teammates noted Anderson looked frail.

After the 2010 World Series had ended, Anderson’s family said that Sparky was in hospice care as he was suffering from the effects of dementia. On November 4, two days after the family’s announcement, Anderson died at age 76.

An earlier version of this biography appeared in “Detroit Tigers 1984: What A Start! What A Finish!” (SABR, 2012), edited by Mark Pattison and David Raglin and SABR’s “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour.

Sources

Anderson, Sparky, with Dan Ewald. They Call Me Sparky. Sleeping Bear Press. 1998.

Anderson, Sparky. Bless You Boys: Diary of the Detroit Tigers’ 1984 Season. Contemporary Books. 1984.

Anderson, Sparky, and Si Burick. The Main Spark: Sparky Anderson and the Cincinnati Reds. Doubleday & Company, Inc. 1978.

Pattison, Mark. “Excerpts From CNS Newsmaker Interview with Sparky Anderson” Catholic News Service, August 29, 1996.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1984\_Detroit\_Tigers\_season

Yuhasz, Dennis. “Sparky Anderson Biography,” http://baseball-almanac.com.