Giants beat Yankees 1-0 to clinch World Series championship – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

The day after the Red Sox sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees the New York Times decreed, “Manhattan’s fondest dreams of having a World Series at the Polo Grounds between the Giants and Yankees now becomes a tangible thing, and that is the big event which New York fans will be rooting for all next Summer.”1 In fact, New York fans would have to root for two summers before their first intercity World Series became tangible, but it was worth the wait.

The day after the Red Sox sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees the New York Times decreed, “Manhattan’s fondest dreams of having a World Series at the Polo Grounds between the Giants and Yankees now becomes a tangible thing, and that is the big event which New York fans will be rooting for all next Summer.”1 In fact, New York fans would have to root for two summers before their first intercity World Series became tangible, but it was worth the wait.

Billed as a battle between Giants manager John McGraw’s old-school “scientific” approach to the game and the new, brash brand of long ball introduced by Yankees slugger Babe Ruth, the 1921 World Series would indeed be played exclusively at the Polo Grounds, home to both teams since 1913, and it would be the last of the best-of-nine World Series.

With no scheduled days off, the clubs alternated home-team honors daily. The Giants hoped to end their streak of four consecutive World Series lost since their 1905 title, while the upstart Yankees, winners of their first American League championship, looked to end two decades of consistent failure with the ultimate victory. By the time the Series concluded, new records were established for ticket sales (269,976) and receipts ($900,233.00),2 and New York Times scribe Irvin S. Cobb was moved to declare that the eight games were played so well and with such splendid sportsmanship that “it should be written that 1921 has wiped the shield of our hemispheric pastime clean of the befouling smear which [the Black Sox Scandal of] 1919 put upon it.”3

However, the excitement that surrounded the first seven games of the 1921 World Series waned considerably by the early afternoon of October 13, when the two clubs arrived for Game Eight. One win away from taking the title, wearing sweaters and mackinaw coats, the Giants gathered around the visitors’ dugout while the Yankees took batting practice. A cold, steady wind cut through the small huddles of early-arriving fans. The Polo Grounds would remain sparsely occupied throughout the afternoon. Just 25,000 witnessed the first pitch of the final game of the 1921 World Series, the upper deck nearly empty. The cold winds and dark sky weren’t the only reasons for the small turnout; a Giants victory seemed a foregone conclusion to many. The Yankees had won the first two games of the series, but the Giants evened the ledger with victories in Games Three and Four. The Yankees won Game Five before losing Games Six and Seven to find themselves on the brink of losing the championship. Most of the games had been competitive and well played, but the Yankees lacked pitching depth and Babe Ruth had been reduced from superstar to spectator by a nagging injury that worsened and now threatened his career.

The 1921 season had been dominated by Ruth. He mashed 59 home runs, and a nation of baseball fans obsessively followed his exploits in newspapers and filled ballparks to see his swing firsthand. With Ruth in their lineup, the Yankees had outdrawn the Giants, their landlords, at the Polo Grounds for the first time in 1920. In 1921, at the age of 26, in just his eighth season in the big leagues (his third as a non-pitcher), the Babe broke the career home-run record of 138 and singlehandedly surpassed the season home-run totals of nine teams. When the second-place Yankees hosted first-place Cleveland for four games over the penultimate weekend of the 1921 season, Ruth led the way, going 8 for 11 with three doubles and two home runs to flip the standings, despite incurring a nasty gash to his left elbow in the third game and re-injuring it the following day.4 The Yankees increased their lead during the final week of the season to win the pennant, but their star limped to the postseason on a tender left knee, his wounded elbow worsening with each passing day.

Ruth started each of the first three games of the Series despite his inflamed elbow and gimpy knee. Following Game Three, the infected elbow swelled to twice its normal size and a three-inch incision was made to drain pus from the wound.5 Ruth was ordered to sit out Game Four. He did not. His arm heavily bandaged, Ruth was praised in the press for playing through the pain. Although he slugged his only home run of the series, he struggled in the field and the Yankees lost 4-2. Ruth again spurned doctor’s orders and started Game Five. The game’s most crucial events unfolded in the top of the fourth when Ruth led off the inning with a surprise bunt single. Bob Meusel then doubled past his brother, Giants left-fielder Irish Meusel, scoring Ruth from first. His sprint around the bases gave the Yankees the lead, but it exacted a toll from the weakened Ruth. According to Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg in 1921: The Yankees, The Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York , “[Ruth] staggered into the dugout, collapsed, and passed out. Dr. George Stewart revived him with spirits of ammonia.” Remarkably, Ruth remained in the game (striking out in his next three at-bats), and the Yankees won. Afterward, Ruth’s attending physician released a statement: “The glands have taken up the poison, as is usual, but the swelling has reached such proportions that if the arm is used it will force the poison into the system, when the poisoning would become general. When blood poisoning becomes general throughout the system, the seat of the trouble must be removed, and that means amputation. Ruth will not play again in the series.”6

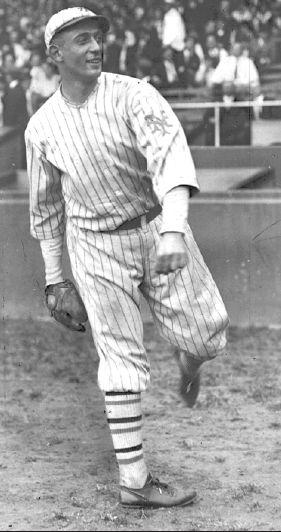

With Ruth relegated to the press box for Games Six and Seven, the Yankees soon found themselves one game from elimination. They had been outslugged in Game Six, and then the Giants’ Phil Douglas outpitched Carl Mays in Game Seven. Waite Hoyt would get the ball for the Yankees in Game Eight. Having already won twice in the series, allowing no earned runs in eighteen innings pitched, Hoyt gave the Yankees a chance to even the series, but then what? Sid Mercer, writing for the Olean (New York) Times Herald, opined, “The Yankees need two games, the Giants one. For the one game McGraw has his choice of two good pitchers [Art Nehf and Jesse Barnes]; for the two games the Yanks have one pitcher [Hoyt]. McGraw is sitting in the golden seat at last after four failures in ten years.”7 To make matters worse for the Yanks, their starting third baseman, Mike McNally, arrived for Game Eight with his arm in a sling, having injured his shoulder in Game Seven.

Hoyt induced a 5-3 groundout to start Game Eight and then issued a pair of walks sandwiched around a foul fly out to first base. Next, the game turned on an ordinary play gone wrong. Roger Peckinpaugh, the Yankees’ shortstop and captain since 1914, misplayed a routine ground ball off the bat of High Pockets Kelly. As the ball rolled into left field, Dave Bancroft scored the final and deciding run of the 1921 World Series. Nehf and Hoyt settled into a pitchers’ duel the rest of the way, and the defenses tightened. When Hoyt left the mound after retiring the Giants in the top of the ninth, his streak of innings pitched without allowing an earned run reaching 27.

With Nehf on the mound to begin the bottom of ninth, Babe Ruth strode to the plate (again against doctor’s orders) to pinch-hit for Wally Pipp. He fouled off the first offering and took the second and third for a strike and a ball. Ruth swung hard at the fourth pitch of the inning but grounded out to Kelly at first. Aaron Ward followed with a walk and Yankees fans’ hopes flickered with Home Run Baker coming to bat. Baker, in the 12th year of his 13-year career, hit a Nehf pitch hard to the hole between first and second. The Associated Press game account reported that “the rap looked like a sure hit and with Ward legging it for third it promised to put the Yankees in a favorable position. . . . But it did not pass. Throwing himself at the skimming sphere, [second-baseman Johnny] Rawlings . . . reached out and clung to it with his left hand. Rolling over and transferring it to his right hand, Rawlings made the throw to [first-baseman] Kelly while still on the ground. . . . It was then Kelly’s turn, and with a lightning-like and accurate throw he shot the ball across the diamond. . . . A cloud of dust flew up over third as Ward slid into the bag. From the midst of it Umpire [Ernie] Quigley’s form emerged, his right arm flung forth, motioning the runner out. The double play had been completed, the third Yankee of the inning had been retired, the game was over, and the Giants had won it and the world championship.”8

Sources

In addition to the sources cited below, box scores can be found at Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet:

https://www.baseball-reference.com/postseason/1921_WS.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1921/B10130NYA1921.htm

Notes

1 William Juliano. “No, No, Frazee: A Look Back at the Reaction Following Babe Ruth’s Sale to the Yankees, The Captain’s Blog, January 6, 2012. http://www.captainsblog.info/2012/01/06/no-no-frazee-a-look-back-at-the-reaction-following-babe-ruths-sale-to-the-yankees/12342/ (“Babe Ruth Accepts Terms of Yankees,” New York Times, January 7, 1920: 22.)

2 Lyle Spatz and Steve Steinberg, Steve_. The Yankees, the Giants, and the Battle for Baseball Supremacy in New York_ (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 387.

3 Irvin S. Cobb, “Fans, Not Players, Quitters, Says Cobb,” New York Times, October 14, 1921: 12.

4 “Ruth 5 Times ‘Out’ on Counts by Physicians,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 13, 1921: 14.

5 “Ruth 5 Times ‘Out’ on Counts by Physicians,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 13, 1921: 14.

6 “Big Series Again On An Even Basis,” Vancouver Sun, October 12, 1921: 8.

7 Sid Mercer, “Pitching Miracle Only Can Save Yanks Victory,” Olean Times Herald, October 13, 1921: 8.

8 “Giants Win World Title; Yankees Die Fighting Hard, 1 to 0,” Oneonta Daily Star, October 14, 1921: 1.