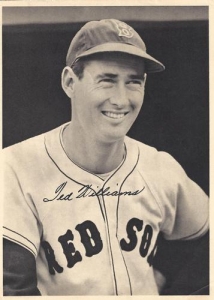

Ted Williams’s inside-the-park home run clinches AL pennant for Red Sox – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

This one was not only a game-winner; it was also a pennant-clincher. And the only inside-the-park homer Ted Williams ever hit. The champagne that had traveled with the Boston Red Sox from Washington to Philadelphia and then to Detroit was again placed on a train and traveled on to Cleveland. One never would have guessed how the Red Sox would clinch the 1946 pennant, though the fact that Ted Williams might be key wouldn’t have been a bad guess. Tex Hughson was the winning pitcher, a 1-0 victory.1

This one was not only a game-winner; it was also a pennant-clincher. And the only inside-the-park homer Ted Williams ever hit. The champagne that had traveled with the Boston Red Sox from Washington to Philadelphia and then to Detroit was again placed on a train and traveled on to Cleveland. One never would have guessed how the Red Sox would clinch the 1946 pennant, though the fact that Ted Williams might be key wouldn’t have been a bad guess. Tex Hughson was the winning pitcher, a 1-0 victory.1

The champagne was indeed shuttled from city to city as the Red Sox, with a commanding 16½-game lead over the pack in the American League after their win on September 5, went on to lose six games in a row. They lost to the Senators on September 6, lost two games to the Athletics on September 7 and 8, traveled to Detroit and lost the two games there on the 10th and 11th. And Bob Feller beat them in Cleveland on the 12th, 4-1.

Even after six losses in a row, they held a 14-game lead over the second-place Tigers, but they still needed one win to clinch.

As it turned out, they needed only one run to clinch.

The Friday afternoon game at League Park was marked by superb pitching from both starters. Both pitchers went the distance. The Indians’ Red Embree gave up only two base hits all game long but took the loss on Friday the 13th in perhaps the best-pitched game of his career. Boston’s Tex Hughson gave up only three hits. There were six walks in the game, four by Embree and two from Hughson. There was one error. With so little action on the basepaths, it’s not surprising that the game took only 88 minutes, start to finish.

Cleveland was in sixth place, 31½ games behind the Red Sox. The game was played before a sparse crowd of 3,295.

Embree started the first by getting Red Sox center fielder Dom DiMaggio to ground out to third base and striking out shortstop Johnny Pesky. Batting third was Ted Williams.

It was Cleveland’s Lou Boudreau who’d more frequently used the extreme shift to defend against Williams. The center fielder, Felix Mackiewicz, was to the right of center field, while left fielder Pat Seerey was “about 20 feet back of the grass behind third base, 15 or so feet from the foul line” – guarding against one down the line. Everyone else was shifted to the right side of the field.

On a 1-and-1 count, Williams– perhaps still remembering Harry Heilmann’s advice – deliberately slashed a ball to left-center and he hit it hard. It would have been, the Boston Globe wrote, “a routine out against an orthodox defense.” But League Park had a very deep left-center field and the Indians’ defense had opened up huge holes on the left side of the field.

Williams’s drive traveled about 375 feet before it hit the ground and then skittered up to 400 or 430 feet before it settled into a gutter at the base of the wall. By the time Mackiewicz got to it, Williams was almost to third base. He slid across home plate as Boudreau’s relay home was a bit off the mark.2

The Cleveland Plain Dealer’s Alez Zirin wrote, “Ordinarily the drive might have been a double, but never a homer.”3

Second baseman Bobby Doerr grounded out, third to first, for the third out.

In the bottom of the inning, Hughson got a couple of groundouts from Mackiewicz and third baseman Don Ross, and Seerey flied out to center field.

Both pitchers retired the side in the second.

The only batter to reach base in the third inning was Embree, who was walked by Hughson.

Walks accounted for three baserunners in the fourth. Embree walked Pesky and first baseman Rudy York. Hughson walked Seerey. Neither team scored.

Red Sox catcher Hal Wagner reached on Embree’s catching error, leading off the fifth. He was sacrificed to second, and took third when Hughson grounded out to first base, Embree covering. DiMaggio grounded out, second to first, ending the inning.

In the top of the sixth, Embree broke up Hughson’s no-hitter by singling to Williams in left-center field. He was sacrificed to second, then took third base when Seerey singled to right field. Embree might have scored the tying run but wisely was held as Red Sox right fielder Tom McBride “made a perfect relay to the plate.”4 Right fielder Hank Edwards grounded one back to Hughson, who threw to York at first base for the third out.

Embree got both of the first two Red Sox batters to foul out in the top of the seventh, then got Wagner to fly out to center. A two-out double by Cleveland second baseman Ray Mack in the seventh gave the Indians another hit but no run. Hughson struck out Jim Hegan to end the inning.

The Red Sox loaded the bases in the top of the eighth on a two-out walk to DiMaggio, a single by Pesky, and a “semi-intentional” walk to Williams, but the score remained 1-0 after Doerr dribbled one to Embree, who threw to first base.5 Pesky’s single was the only base hit in the game off Embree after Williams’s first-inning home run.

It was three-up, three-down for the Indians in the bottom of the eighth, and the same for the Red Sox in the top of the ninth.

The Indians entered the bottom of the ninth just trailing by one run – the home run Williams had hit back in the first inning.

Seerey took a called third strike. Edwards flied out to right field. So did their last hope, first baseman Les Fleming.

The game was over, 1-0 in favor of the Red Sox, and the well-traveled champagne could finally be uncorked – after the players got the news that the Yankees had defeated the Tigers in Detroit.

The _Boston Globe_’s headline the next day proclaimed, “Weird Indian Defense Finally Boomerangs to Give Sox Pennant.”6 Nonetheless, Williams wanted to give Tex Hughson all the credit for the win. “He pitched a helluva game. My home run didn’t mean a thing when I hit it.”7

Williams, years later: “Someone said, ‘Is that the easiest homer you ever got?’ And I said, ‘Hell no, it was the hardest. I had to run!’”8

It was Williams’s 38th home run of the year, a new season high. It was also his last of the year – and he didn’t hit one in the World Series, either. It was a tough World Series, the only one in which Williams ever played. Injured just beforehand, he hit only .200. The Red Sox lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games.

The pennant was the first one the Red Sox had won in 28 years. It was manager Joe Cronin’s second, though. He had won one as the 26-year-old player-manager of the Washington Senators in 1933.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CLE/CLE194609130.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1946/B09130CLE1946.htm

Notes

1 So began the account of Ted Williams’s 165th career home run in Bill Nowlin, 521: The Story of Ted Williams’ Home Runs (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2013), 108.

2 This paragraph comes in its entirety from Nowlin, 521: The Story of Ted Williams’ Home Runs, with permission. Heilmann’s advice had come two days earlier. Heilmann, a local broadcaster in Detroit at the time, sat on the bench with Williams before the game and told him he ought to be able to hit .400 again (as Heilmann had done himself in 1923) if he’d consistently bunt toward third base whenever they pulled the shift on him. “You can bunt yourself into leading the league in hitting. …What Ty Cobb would do with that sort of defense would be to get 4-for-4 every game.” See Burt Whitman, “Tigers Clout Ferriss, Check Sox 7-3,” Boston Herald, September 12, 1946: 15.

3 Alex Zirin, “Red Sox Nail First Flag in 28 Years,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 14, 1946: 11.

4 Zirin.

5 Hurwitz had thus characterized the walk to Williams.

6 Hy Hurwitz, “Weird Indian Defense Finally Boomerangs to Give Sox Pennant,” Boston Globe, September 14, 1946: 2.

7 Ed Linn, Hitter: The Life and Turmoils of Ted Williams (New York: Harcourt & Brace, 2003), 212.

8 Ted Williams with John Underwood, My Turn At Bat (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969), 111.