Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium – Society for American Baseball Research (original) (raw)

From its beginning, as a plank in Ivan Allen’s campaign platform for mayor, to its end, hosting the Olympic baseball competition and a World Series in its final year of existence, Atlanta Stadium was a major part of the push to make Atlanta a world-class city.1 The stadium succeeded in attracting teams from major-league baseball, the National Football League, and even the North American Soccer League. But the teams vacated the premises of 521 Capitol Avenue SE2 for alternate local venues, one by one, until the stadium was demolished on August 2, 1997, to make room for a parking lot to serve the Braves’ new home.

While Braves fans were celebrating their World Series championship in 1995, it was very clear that the end was in sight for Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. For at least 10 years there were suggestions and plans to renovate the stadium or move the Braves somewhere else. From a venue that was celebrated as sparkling and amazing in 1965 to a site enclosing the doldrums and non-sports-like hijinks of the dismal ’80s to the astonishing, almost magical resurrection of the “Worst to First” Braves of 1991 and their sudden power of the mid-’90s, the 31-year story of the stadium needs to be retold, as it is fading from sports memory in contrast to new playing fields, a Hall of Fame cast of pitchers and manager, and 14 consecutive playoff appearances.

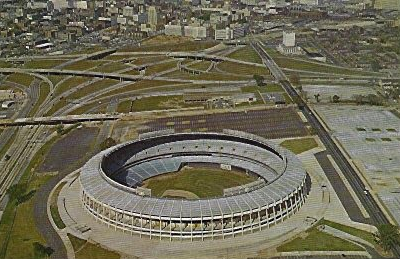

Soon after his 1962 inauguration, Allen was told by Atlanta Journal sports editor Furman Bisher that the Kansas City Athletics’ owner, Charlie Finley, was coming to Atlanta to look for potential stadium sites. Allen and Bisher showed Finley four sites; when he saw the last, at the junction of I-75/85 and I-20 a mile south of downtown, he told them, “This is the greatest site for a stadium I’ve ever seen. If you build it, I’ll bring the Athletics here as soon as it’s finished.”3 The American League declined to approve this deal, but when the Milwaukee Braves were induced to move to Atlanta instead, plans for the stadium swiftly took shape.

Having developed a strong friendship with local architect and civic leader Cecil Alexander, Mayor Allen wanted his firm to design the facility. The head of the stadium authority preferred another firm, so the architects were compelled to form a joint venture, Finch-Heery Architects, which went on to design many other ballparks. Alexander did on-site research at Yankee Stadium, Shea Stadium, Busch Memorial Stadium, and D.C. Stadium (later renamed RFK Stadium). He gave his notes to his partner Bill Finch,4 who designed a circular stadium, with playing dimensions 325 feet down the lines and 402 feet to straightaway center, built in 51 weeks at a cost of $18 million.5

The Stadium: A Functional Arena or a “Concrete Doughnut”

Twenty years after the closing of the stadium, a baseball and art critic remembered the architectural design of the stadium. Both of the architects “embraced a modern quasi-minimalistic ‘international style,’ … that prioritized function over form, certainty over décor. Shunning traditional Southern esthetics, Atlanta Stadium (as it was first called) was like many of the other multipurpose stadiums that would be built in the 1960s — contemporary but sterile, practical but domesticated, bureaucratically formed to appease both football and baseball sensitivities within the same space.”6 More simply and critically, “one sports writer derided Atlanta Stadium and the other stadiums constructed in this era as ‘concrete doughnuts.’”7 Such constant criticism irritated Atlanta sportswriter Jim Minter, whose exuberant reporting of that first opening weekend had reached high enthusiasm: “Atlanta Stadium is in the right place. It is precisely the right place. Anywhere else would be poor business and an abandonment of the ‘undaunted, unconquerable, unsurpassed Atlanta spirit,” which was alive and well a short two decades ago. … The real problem with major league sports in Atlanta is not the stadium, but rather the consistently disappointing performances of the teams playing there.”8

In the words of the baseball/art critic mentioned above, “sky-blue hues echoed throughout the otherwise white stadium, from the 50,000 plus wooden seats across three decks (including a petite second level partly reserved for media) to its upper deck overhang rim with horizontal Latin banks rather than the tall towers of electric lamps used in older facilities.9 In 1977 the stadium was remodeled with plastic seats, light blue on the field level and orange in the upper deck.

Atlanta Stadium: The Early Years

Although the Braves originally planned to move to Atlanta for the 1965 season, an antitrust suit filed by the City of Milwaukee against the Braves postponed the move for a year, so Atlanta Stadium hosted the last season of the International League’s Atlanta Crackers in 1965. The first game at the stadium, however, was an exhibition game between Milwaukee and Detroit on April 9, 1965. Milwaukee won the game, 6-3, in front of 27,232 fans. Tommie Aaron hit the first home run there, a three-run shot in the first inning. Although traffic and parking problems delayed the start of the game, and long lines at the unfinished concession stands caused some irritation for fans, Atlanta Stadium’s inauguration was generally viewed as a huge success for the city.10 On April 17 the Crackers opened their 1965 season with a victory over the Rochester Red Wings and then proceeded to sweep the three-game weekend series, just as the parent club had done to Detroit the previous weekend. The Crackers finished their only season in Atlanta Stadium in second place with a record of 83-64 and drew slightly more than 150,000 for the season.11

The Braves opted to proceed with the move in 1966 despite the lawsuit, which was eventually decided in favor of the team.12 The Atlanta Braves debuted in their new home at 8:11 P.M. on April 12, 1966, before a capacity crowd of 50,671 fans, losing 3-2 to the Pirates.13 Joe Torre hit the first regular-season major-league home run in the ballpark in the fifth inning and added another in the bottom of the 13th. Although the Braves won a couple of division championships (1969, 1982) prior to their unprecedented title run beginning in 1991, Atlanta Stadium was, for the most part, the home of long stretches of bad baseball and paltry attendance for much of the 1970s and 1980s.

The Launching Pad

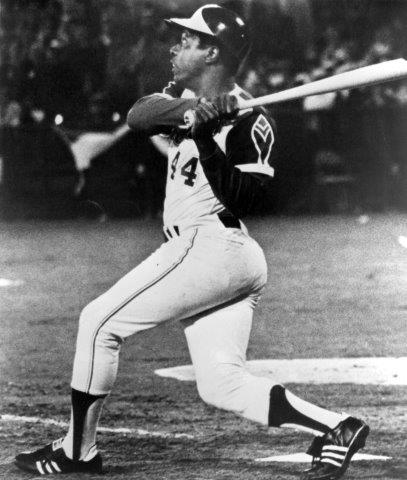

The stadium is best known as the site of Hank Aaron’s 715th home run, launched into the Braves’ bullpen just beyond the left-center-field fence on April 8, 1974. As Aaron circled the bases, the team’s Native American mascot, “Chief Noc-a-homa,” emerged from his tepee in the left-field stands to celebrate the home run with his customary war dance.14 After moving to Atlanta, Aaron changed his stance, bringing his hands closer to his body.15 He made himself into a pull hitter and became one of the few players to see his home-run totals increase after the age of 35, helped by the 1,050-foot elevation of a new home park that became known as “The Launching Pad.”16 The stadium seemed to have left its mark on the Braves, who continued to base their offense around the home run even after moving into the more pitcher-friendly Turner Field.

The stadium is best known as the site of Hank Aaron’s 715th home run, launched into the Braves’ bullpen just beyond the left-center-field fence on April 8, 1974. As Aaron circled the bases, the team’s Native American mascot, “Chief Noc-a-homa,” emerged from his tepee in the left-field stands to celebrate the home run with his customary war dance.14 After moving to Atlanta, Aaron changed his stance, bringing his hands closer to his body.15 He made himself into a pull hitter and became one of the few players to see his home-run totals increase after the age of 35, helped by the 1,050-foot elevation of a new home park that became known as “The Launching Pad.”16 The stadium seemed to have left its mark on the Braves, who continued to base their offense around the home run even after moving into the more pitcher-friendly Turner Field.

The “Launching Pad” reputation was born in early 1966 when the team bus was returning from a road trip and the new pitchers stood up to get their first look at the stadium: “Veteran pitcher Pat Jarvis told them, ‘There it is, boys. Welcome to the Launching Pad. You might as well get used to it. The ball really jumps outta there.’ That was it. Atlanta Stadium was forever nicknamed for the pitchers of the National League.”17 The longest home run hit at the stadium was 475 feet by the Cubs’ Willie Smith, June 10, 1969.18 During the 1996 Summer Olympics Cuba’s Orestes Kindelan hit a ball 521 feet.19

After Aaron: The Doldrums of the 70s and 80s

After Ted Turner purchased the Braves in 1976, Atlanta Stadium hosted weddings at home plate, Fourth of July fireworks, and ostrich races around the warning track in an attempt to boost dwindling attendance.20 The ostriches weren’t always confined to the warning track: Skip Caray recalled steering his bird directly from center field to home plate to steal a win.21 Nor were the fireworks necessarily confined to July Fourth: the 1985 fireworks show started at 4:01 A.M. on July 5 after a 19-inning defeat and caused many of the stadium’s neighbors, awakened by the noise, to fear that the area around the park had become a war zone.22 The City of Atlanta soon made it illegal to start fireworks shows after midnight. Responsibility for caring for the playing surface was transferred from the Atlanta municipal street-maintenance crew to a full-time groundskeeper in 1989.23 When John Schuerholz became general manager in 1990, Ed Mangan came with him from Kansas City and greatly improved the field conditions.

The New Miracle Braves

The teams that took the field also improved greatly under Schuerholz. The Braves went from “worst to first” in the NL West in 1991, losing to the Minnesota Twins in a riveting World Series that fall. In 1993 the Braves drew a franchise-record season attendance of 3,884,720. The Braves were nine games behind the Giants in the NL West standings on July 20, 1993, when a pregame fire in the press box coincided with the arrival of first baseman Fred McGriff, who had been acquired in a trade with the San Diego Padres. Together, the press box conflagration and McGriff lit a fire underneath the Braves, who went 50-17 over the remainder of the season to secure the NL West flag.

Two of the stadium’s most enduring moments came in the postseason during the club’s resurrection in the 1990s: Francisco Cabrera’s ninth-inning, two-out pinch-hit single in Game Seven of the 1992 NL Championship Series, culminating in Sid Bream’s dramatic slide into home with the game- winning run, clinched the Braves second consecutive NL title; and when center fielder Marquis Grissom caught a fly ball to complete a combined one-hit shutout by Tom Glavine and Mark Wohlers on October 28, 1995 in Game Six of that year’s World Series, the stadium finally hosted its first (and only) major-league championship. But by then the Braves were already looking forward to taking over Atlanta’s 1996 Olympic Stadium, built on an adjoining lot, which would be reconfigured for baseball before the 1997 season and renamed Turner Field. The Braves played their last game in Atlanta Stadium on October 24, 1996, a 1-0 loss to the New York Yankees in the fifth game of the 1996 World Series.

That 1996 Series was indeed a bitter loss, for the team that year was an especially gifted one: It won a franchise record 56 games at home, hit .270, and homered 197 times (third-best ever for the team during the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium years). The stellar pitching staff was one of the best in baseball, with John Smoltz (24-8 with 2.94 ERA), Greg Maddux, 15-11 with a 2.72 ERA, and Mark Wohlers saving 39 games. They swept the Dodgers in three games and rallied from a three-games-to-one deficit to beat the St. Louis Cardinals in the best-of-seven NLCS. In the World Series they beat the Yankees the first two games in Yankee Stadium, and appeared well on the way to consecutive World Series titles. However, because of bad luck and bad playing in the field, they lost the next four games. The fourth game was the turning point. After the Braves led 6-0 into the sixth inning, the Yankees scored three runs on a misplayed pop foul and a two-run, two-base error, and then tied the game in the eighth on an infield hit, a force out on what should have been an inning-ending double-play ball, and a three-run homer. In the 10th, a two-out walk, an infield single, and an intentional walk followed by another walk, and a misplayed infield fly resulted in the two runs for the final score: Yankees 8, Braves 6. After this disaster and another error-causing loss, 1-0, in the fifth game, the collapse was completed with a 3-2 loss back in New York.24

Other Sports and Events at the Stadium

Like the Braves, the Atlanta Falcons, a newly created National Football League team, played their first season in 1966, and they remained at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium until the Georgia Dome opened in 1992. The Falcons opened on September 11, 1966, losing to the Los Angeles Rams 19-14. They finished that first season 3-11. Though the Braves had occasional pennant winners and one World Series championship, in their 26 years at the stadium the Falcons played in only six postseason games, advancing to the second round only twice. Only six of those 26 years were winning seasons, with the low point in attendance a game against Green Bay drawing only 10,000 fans. The Falcons’ regular-season record over 26 years was 144 wins, 235 losses, and 5 ties, a .380 winning percentage, and a little better at home: 85-105-2, .438. If these generally mediocre years did not greatly appeal to the fan, the layout of the football field at the stadium was even more unsatisfactory: it was turned so that anyone sitting on the 50-yard line was 50 yards away from viewing.

College football soon came to the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium in the form of the newly established Peach Bowl. The games were usually between teams from the Atlantic Coast Conference and the Southeastern Conference, with occasionally teams from the Big Ten and the Midwest. From 1968 through 1971 the game was played at Grant Field, and the most noteworthy aspect of the first four games was respectively the bad weather: cold wind, driving rain, swirling snow, and rain and mud. From 1971 through 1992, the Peach Bowl game was played at Atlanta- Fulton County Stadium, 21 games in all, including 11 teams in the Top 20, the highest ranked being the last one, New Year’s Day 1992, with number 12 East Carolina defeating its intrastate rivals number 21 NC State 37-34. With the Georgia Dome opening in 1992, the games found a warm, dry, and impressive venue, thereby becoming eventually one of the top six postseason bowl games.

During the summer of 1996 — and in the middle of the baseball season and while the Braves were on an extended road trip — the baseball games on the 1996 Summer Olympics were held at Atlanta- Fulton County Stadium from July 20 through August 2. Eight nations participated (Cuba, Japan, the United States, Nicaragua, Netherlands, Italy, Australia, and South Korea), playing each other in 28 preliminary games and the top four moving on to the semifinals and final. Cuba, which was undefeated in the preliminary rounds, defeated Nicaragua 8-1 and Japan defeated the United States 11-2. The United States won the bronze medal 10-3 over Nicaragua, and Cuba finished undefeated, winning the gold 13-9 over Japan.

Summary — and an Image of the Past

In their time at the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, the Braves won 1,265 games and lost 1,166, 99 more wins although being outscored by 126 more runs. Overall, the Braves record was 2,388 won and 2,493 lost, a .489 average. The team batting average was .254, with 4,293 home runs, 19,053 RBIs, 20,350 runs, and 42,044 hits.

A small section of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium’s left-field wall, the site of Aaron’s 715th home run, was left standing when the area was transformed into a parking lot next to Turner Field. Late in 2013, the Braves announced that they would leave the latter park behind as well and move to the northern suburbs. Beginning in 2017 the Braves played at SunTrust Field in Cobb County.

When the Braves abandoned Turner Field for SunTrust Park, Georgia State University purchased the facility and made it into a more oval-shaped football stadium with a memory of Atlanta Fulton County Stadium: “[T]he outfield wall will fuse in the memorial remnant of Aaron’s 715 home run. Thus, anyone who attends the Georgia State baseball game in the near future can relax, kick back, and imagine the stadium that once surrounded the field and helped introduce Atlanta into the big leagues.”25

Acknowledgments

This article represents a revised and expanded version of an earlier article by Scott McClellan, which appeared as part of SABR’s BioProject.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Pro Football-Reference.com, homeofthebraves.com, and Reidenbaugh, Lowell. Take Me Out to the Ball Park (St. Louis: The Sporting News Publishing Co., 1986).

Notes

1 The stadium was originally referred to as “Atlanta Stadium.” The names “Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium” or just “Fulton County Stadium” saw common usage starting a few years later. It is unclear exactly when any given name became the “official” title.

2 The stretch of Capitol Avenue near the site of Atlanta Stadium and its successor, Turner Field, was renamed “Hank Aaron Drive” in 1997.

3 Cecil A. Alexander, Crossing the Line (Atlanta: W&C Publishing, 2012), 141.

4 Alexander, 142.

5 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals (New York: Walker & Company, 2006), 9.

6 Eric Gouldsberry, “The Ballparks: Parks of the Past, Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium,” This Great Game. Accessed 27 January 2020. thisgreatgame.com/ballparks-atlanta-fulton-county-stadium.html.

7 Quoted in Kenneth R. Fenster, “Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium,” in New Georgia Encyclopedia, December 10, 2019. Accessed January 29, 2020. georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/sports-outdoor-recreation/atlanta%E2%80%93fulton-county-stadium.

8 Jim Minter, “Clean Up Atlanta Stadium and Leave It Where It Is,” Atlanta Constitution, March 3, 1985: 94.

9 Gouldsberry.

10 Marion Gaines, “37,232 Watch Braves Cage Tigers, 6-3, in Rousing Debut of Stadium,” Atlanta Constitution, April 10, 1965: 1. The Braves swept the three-game exhibition series from the Tigers, which drew 106,000 fans.

11 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2007). The Crackers were relocated to Richmond, Virginia, for the 1967 season, and renamed the Richmond Braves.

12 Bob Klapisch and Pete Van Wieren, The World Champion Braves: 125 Years of America’s Team (Atlanta: Turner Publishing Inc., 1996), 134-135.

13 Ira Rosen, Blue Skies, Green Fields (New York: Clarkson Potter/Publishers, 2001), 24. Stadium capacity was typically cited as 52,000 in the local media.

14 Rosen.

15 Jack Wilkinson, Game of My Life (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, LLC, 2007), 106.

16 Bill James, The Bill James Historical Abstract (New York: Villard Books, 1988), 416.

17 Ed Hinton, “Science Can’t Explain Stadium’s ‘Missiles,’” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, April 5, 1981: 9C. This article includes a table showing the home runs hit in the National League ballparks from 1976 to 1980, with Atlanta- Fulton County Stadium having for that period more than 100 over the nearest competitor (799 over Wrigley Field’s 690). The article interviews scientists as well as Braves sluggers Dale Murphy and Bob Horner in an unsuccessful attempt to explain the “Launching Pad.” However, an analysis of total home runs from Baseball-Reference.com reveals that in the 31-year-period of the stadium, 4,617 home runs were hit there (the Braves hitting 2,385); whereas for the same period of years, Fenway Park had 4,625 and Wrigley Field 4,621. So Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, during the period in question, is third in number of total home runs hit, averaging 148.9 per season in contrast to the overall 31-year period of 153.9. Interestingly, for the 20 years that the Braves occupied Turner Field, the average was almost the same, 150.4. The real “Launching Pad” might be SunTrust Park, in which for three years the home run average was 182.7. These are all total home runs, Braves and opposing teams.

18 Charley Roberts, “Smith HR Equal to Poncey Pokes,” Atlanta Constitution, June 17, 1969: 39.

19 Tom Whitfield and Joe Strauss, “Day 5: Baseball Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium,” Atlanta Constitution, July 23, 1996: 85.

20 John Pastier, Ballparks, Yesterday and Today (Edison, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, Inc., 2007), 98.

21 Wilkinson, 130.

22 Lowry, 9.

23 Eric Pastore, 500 Ballparks (San Diego: Thunder Bay Press, 2011), 41.

24 Jay Jaffe, “The 1996 Yankees and the Epic Comeback That Started Baseball’s Last Dynasty,” Sports Illustrated, August 26, 2016. si.com/mlb/2016/08/1996-yankees-reunion-world-series.

25 Gouldsberry.