Strathcona (original) (raw)

Strathcona | EAST SIDE

Strathcona Harvest Festival

Strathcona fire hydrant love on a hot day

Strathcona overpass

The Wilder Snail - Crawl Weekend 2

Great drape

Parker Street Studios

Strathcona is Scout’s home base and Vancouver’s oldest neighbourhood. Before it was called Strathcona (a later honorific) it was known as The East End. And for centuries before that it was a seasonal camp called Kumkumalay (“big leaf maple trees”) that was regularly employed by Coast Salish First Nations. Today, it is the easternmost slice of the Downtown Eastside (DTES), bordered on the west and east by Gore and Clark, and on the north and south by Powell and Venables/Prior. Though the 200 block of Union St. can be seen as part of Chinatown, its redevelopment and the flow of its bike route have made it more a piece of Strathcona. Though today it is widely considered a hip hotbed of artistic creativity (witness the annual Eastside Culture Crawl, etc.), the cozy quarters of roughly 10,000 people nevertheless remains on the sedate side of urban.

Strathcona’s residential, my-garden’s-got-its-shit-together community feel might surprise outsiders, especially considering its proximity to the city’s heart and its umbilical connection to the oft-demonized DTES. But the people hereabouts – mostly low income, working class – are fierce in their affections for their home turf; not possessive of property so much or excessively house proud, just firmly rooted. The neighbourhood’s ethnic diversity is as much its strong suit as its tough, activist spirit. It is the only neighbourhood in Vancouver where English is not the mother tongue of the majority of the inhabitants (Chinese languages predominate), but when pushed by the City with ill-considered plans – whether it be a freeway or a rushed amendment to a bike lane – its population has a habit of quickly coalescing to fight back, differences be damned.

Strathcona is anchored by a green space called MacLean Park, which plays host to all manner of community events, from casual Sunday pick-up games of soccer and on-the-fly weddings to harvest festivals and multi-family get-togethers. In the summer, the aromatic smoke of BBQs hangs low over the field, with leisure supplies replenished from the area’s four chief corner groceries (The Wilder Snail, Wayne Grocery, Union Market, Benny’s) and the nearby Astoria Pub’s off-sales shop. Strathcona Park (on the south side of Prior St.), though considerably larger than MacLean, is less of a community hub, but it does offer a fun little skatepark, tennis courts, and multiple baseball fields (there’s a great Spring/Summer/Fall beer game every Saturday afternoon).

Strathcona Elementary School brick (the older buildings); alleyway sofa standard orange; the summer green grass of McLean Park; loud and aggressive crow black; the glass-like tar/asphalt of the 500 block of Keefer St.; Pilsener label tri-colour; La Casa Gelato exterior; needle plunger blue; Benny’s Market burgundy; Strathcona Community Gardens; sketchy 1/2 naked drunk guy in the park.

PEDAL POWERED ELECTRICITY AT THE WILDER SNAIL

OFF SALES OF COLD BEER AT THE ASTORIA

THOUSANDS OF CROWS MARSHALLING FOR THEIR NIGHTLY BURNABY ROOST

THE BEST CHEESE STORE IN THE WEST

SMEAGOL & DEAGOL THE EAGLES

HOUSES THAT ARE STRANGELY SET HIGH ABOVE OR BELOW THE SIDEWALK

LOUD COOPER’S HAWKS HUNTING FOR PIGEONS

A FANTASTIC LITTLE VINYL SHOP

ARTIST STUDIO VISITS DURING THE EASTSIDE CULTURE CRAWL

THE SMELL OF INCENSE FROM THE PTT BHUDDIST TEMPLE ON KEEFER ST.

SHOCKINGLY GOOD RAMEN AT HARVEST 243 Union St. MAP

CAPPUCCINO AT THE WILDER SNAIL 799 Keefer St. MAP

CHICKEN CURRY POCKETS AT UNION MARKET 810 Union St. MAP

LEMON FUDGE SORBET AT LA CASA GELATO 1033 Venables St. MAP

CAPICOLLO SANDWICHES AT BENNY'S MARKET 598 Union St. MAP

BLUE BRIE AND PROSCIUTTO SANDWICHES AT FINCH'S 501 E Georgia St. MAP

![Rear and west side view of building [219 - 221 Prior Street] copy](https://farm8.static.flickr.com/7458/14067871774_4613439c92_b.jpg)

Rear and west side view of building [219 - 221 Prior Street] copy

hogansalley2 copy

Fielding William Spotts copy![830 Dunlevy Avenue [and] 844 Dunlevy Avenue copy](https://farm8.static.flickr.com/7350/14064241092_852e4b0171_b.jpg)

830 Dunlevy Avenue [and] 844 Dunlevy Avenue copy![800 - 804 Main Street [at Union Street] copy](https://farm8.static.flickr.com/7345/14067873794_7acebb1bff_b.jpg)

800 - 804 Main Street [at Union Street] copy![259 Prior Street [Chou Doely Gam cabins back] copy](https://farm8.static.flickr.com/7356/14067874334_3692f01ec5_b.jpg)

259 Prior Street [Chou Doely Gam cabins back] copy![251 Prior Street [front] copy](https://farm8.static.flickr.com/7037/14087453623_97256e22da_b.jpg)

251 Prior Street [front] copy

249 Prior Street copy![248 - 250 Union Street [front] copy](https://farm6.static.flickr.com/5482/14067411525_0228fe0e82_b.jpg)

248 - 250 Union Street [front] copy![232 - 240 Union Street [front] copy](https://farm8.static.flickr.com/7406/14044297646_8b12201c61_b.jpg)

232 - 240 Union Street [front] copy![218 Union Street [front] copy](https://farm6.static.flickr.com/5004/14067412145_43a1c195e7_b.jpg)

218 Union Street [front] copy

Sun July 19, 1952 2 of 2

Like most cosmopolitan cities around the world, Vancouver is known for its distinct neighbourhoods, each with their own character, landscape, and history. But what happens when an entire neighbourhood is razed to the ground and its community is displaced? The historic Hogan’s Alley in Strathcona is a unique example of how a neighbourhood can come to define the history of a group of people, and the intricacies of cultural identity in an urban space.

The name “Hogan’s Alley” is often explained as being the colloquial term for Park Lane, an alley that spanned from Main Street to Jackson Avenue between Union Street and Prior Street, and the surrounding area. The lane, which ran parallel to Main Street, did originally border the sides, backs, and gardens of homes, but to consider the whole neighbourhood as simply an “alley” would be a disservice to the businesses, residences, and cultural centres that developed around it.

Hogan’s Alley was not marked on the city map in any particular fashion, and its precise boundaries are not entirely clear. City archivist J.S. Matthews noted on a photo from 1891 that the lane adjacent to the home at 209 Harris Street (now East Georgia) was known as Hogan’s Alley; from where exactly he learned the nickname is unknown.

While the definitive nomenclature is still up for debate, what is clear it that multiple generations of families and workers, predominantly of African-Canadian descent, called this area home for decades. Ultimately, many of these families were displaced when the City demolished a number of homes and businesses in Hogan’s Alley to build the second version of the Georgia Viaduct.

The black community which came to define Hogan’s Alley came to the area shortly after the turn of the century. Many individuals had come from Vancouver Island, likely in search of work in local resource industries, and this section of Strathcona (then known simply as the East End) quickly developed into a mecca for those of African-American and African-Canadian heritage. Many had also migrated to Vancouver from California and Louisiana. At this time, Vancouver was seen as having limitless economic potential.

Prior to his political defeat in 1934, Mayor L.D. Taylor had a unique and often controversial perspective of how Vancouver should mitigate the growing crime rates in the city. In particular, his “open town policy” on vice crimes such as prostitution, gambling, and illegal drinking meant that areas such as Hogan’s Alley were ripe for these types of “victimless” crimes to continue unchecked. Moreover, his ties to corruption in the police department further frustrated those who recognized the fragile state of the city’s lower-income neighbourhoods. Given Hogan’s Alley’s proximity to transportation centres and the commercial hub of Hastings Street (the very same reasons residents were drawn to the area in the first place), it attracted a wide variety of legal and illegal activities for locals and visitors in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Park Lane itself was only 8 feet wide and spanned only a couple of blocks, but the area was filled with a variety of after-hours entertainments, including bootlegger establishments, cheap eateries, and popular brothels. These businesses, popular with loggers, sailors, and other resource industry workers, included Buddy’s on Union for booze, the Scat Inn on Park Lane for music and food, and even a back-alley wine merchant called Lungo. All this – including stories of a blind prostitute known as the “Queen of Hogan’s Alley” – led to a rough-and-tumble reputation that scared many folks off and intrigued even more.

While Hogan’s Alley was a predominantly black community (Vancouver’s first), there were other cultures and ethnicities prevalent in the area as well. Several Jewish families and business were well established and an Italian consular office was located in the Bingarra Block at Union and Main. Some of the houses on the 200-block of Union Street, which became vacant during World War I, later became home to Chinese families.

It is important to note, however, that this area was once a comfortable community for Vancouver’s black population. Indeed, while other ethnically defined areas are historically common in Vancouver (Little Italy, Chinatown, Japantown, etc), this was the first – and only – example of a cultural enclave for African-Canadians. It is also the site of Vancouver’s first black church, the African Methodist Episcopal Fountain Chapel (823 Jackson Avenue), which was purchased by the community in 1918.

During its heyday in the 1930s and 40s, Hogan’s Alley featured a number of black-owned businesses that added a distinct southern flavour to the neighbourhood. One of these black-owned businesses was Emma Alexander’s Mother’s Tamale and Chili Parlour at 250 Union Street. Emma’s niece, Viva Moore, later opened the famous Vie’s Chicken and Steak House at 209 Main Street, which operated from 1948 until 1976. Run by Viva and her husband Rob, the restaurant was a popular spot for locals and even a few famous faces, including Nat King Cole and Louis Armstrong. Sadly, the unique culture and popularity of businesses like these, and the fact that a growing community was thriving in the area, wasn’t enough to protect the neighbourhood from “progress”. Eventually, Hogan’s Alley’s reputation as a red light district gave Mayor Tom Campbell’s government the justification to approve the $11.2 million Georgia Viaduct Replacement project.

Since its destruction in the early 1970s, the surrounding area has evolved from a primarily residential neighbourhood into a growing commercial sector, with a number of shops, cafes, and restaurants along Union Street catering to a new generation of Vancouverites. Modern civic and cultural organizations, such as the Hogan’s Alley Memorial Project, help memorialize and educate people on the experiences of black individuals in Vancouver, as well as the history of Hogan’s Alley.

The Jimi Hendrix Shrine at the corner of Main and Union (adjacent to the former site of Vie’s Chicken and Steak House) pays homage to the musician and his grandmother, Nora Hendrix, who migrated to Vancouver from Tennessee in 1911 and worked at Vie’s restaurant. Nora’s home at 827 East Georgia still stands today, where she raised three children with her husband Ross. In 2013, the Vancouver Heritage Foundation’s Places That Matter program installed a plaque near the Hogan’s Alley Cafe in conjunction with Black History Month. While most tangible remnants of this historic neighbourhood are long gone, the legacy of its community and its place in the story of Vancouver is, thankfully, still remembered and celebrated.

– Union Street used to be called Bernard Street – it was renamed in 1911 to avoid confusion with Burrard Street

– In the late 50s and 60s city planners stopped public works maintenance in Strathcona, denied redevelopment permits, and bulldozed 15 blocks of homes as part of an “urban renewal” project for this supposed “slum”.

– Vancouver’s only neighbourhood with a concentrated Black population, Park Lane (known colloquially as Hogan’s Alley), was demolished in 1972 to construct the Georgia Viaduct.

– In 1985 the Strathcona Community Gardens were established at Campbell Avenue and Prior Street, an area that in Vancouver’s early years had served as the City Dump.

– Strathcona used to simply be called the East End; the new name was adopted in the 1960s.

– Jackson Garden apartments on East Pender echo the compound/alley style of Hutong residences once popular in China, and were specifically designed to accommodate Chinese residents in Strathcona.

Welcome

Board of Trade, Strathcona

U Go To Store | A piece of Strathcona History

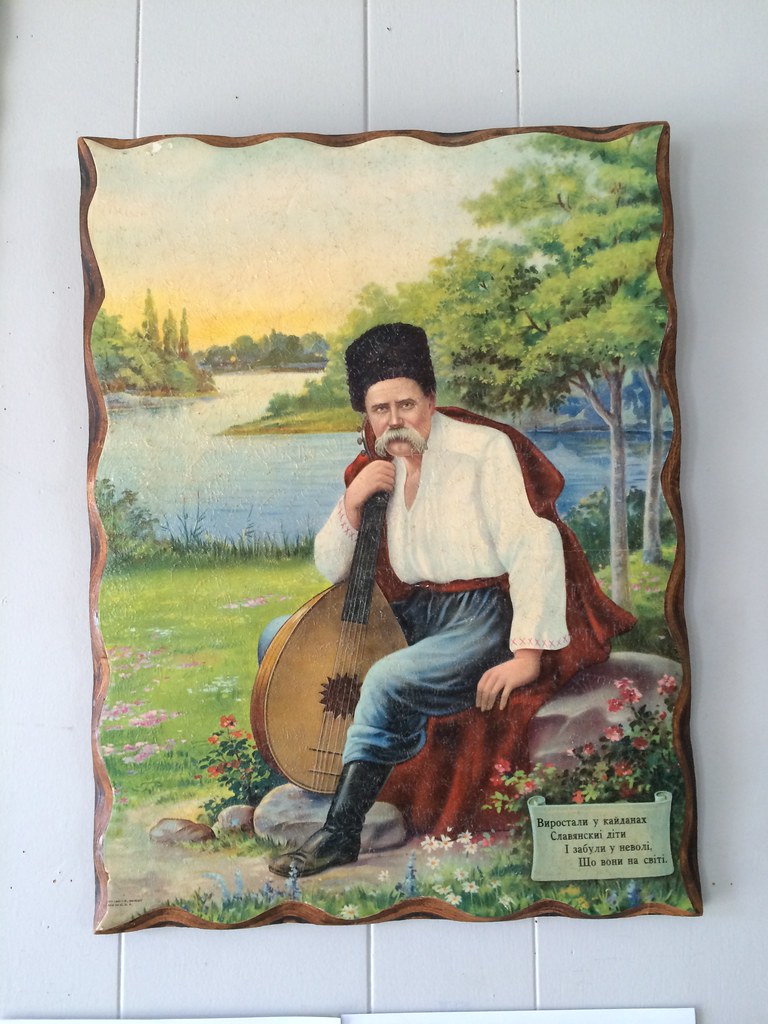

Ukrainian Cultural Centre in Strathcona

Strathcona Spring Sky

Pub With No Beer? Vintage vinyl score at Ukrainian Cultural Centre in Strathcona

Ukrainian Cultural Centre in Strathcona

Lisa Ochowycz | Mergatroid Building | Eastside Culture Crawl

Ladies at the Strathcona Harvest Festival

1000 Parker Street

Strathcona Puddle

Blurry Strathcona

Strathcona Community Gardens Piano

Strathcona Labyrinth

Finch's tea house Strathcona

Strathcona

Nothing Else Mattress

Strathcona Kid

The Empire Strikes Back Curtains in Strathcona

Lilacs | Strathcona

Birdie | Strathcona Mascot

Russian Treats at the Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Church Open House & Food Fair

Strathcona Houses all in a row

MacLean Park, Strathocna

House Made Dan Dan Noodles - spinach, tofu croutons, chiles, sichuan peppercorn sauce | The Parker

Flatbush - Alberta Premium Rye, Saltspring balckberry, Punt e Mes Saline | The Parker

Strathcona T

Strathcona Treasures

Gore Street Houses, Strathcona

Strathcona Dragons

Skating through Strath

The Union

Lord Strathcona School

Puddle day | Strathcona

Strathcona Harvest Festival

Tracks

Finch's Tea & Coffee House

Strathcona Heritage Hosue

Strathcona Soccer Club

Ramen at Harvest

Hawk

Grab-a-book

Harvest Community Foods

Jamie at Finch's during construction

Union Street | Strathcona | Scout Magazine

Dunlevy Snackbar

Strathcona Door

Strathcona family

Spring street drain

McLean Park, Strathcona

Maclean Park, Strathcona

Enjoying a jacked fire hydrant on a hot day in Strathcona

Gentrification

Strathcona Houses at sunset

Strathcona East Side Culture Crawl 2 154©Scout 2009

Hazel in the park | Summertime | Strathcona

Strathcona Soccer Club

Pies Pies Pies Pies at the Strathcona Harvest Festival

Eastside Culture Crawl | Strathcona

Dunlevy Snackbar | 433 Dunlevy

Strathcona Harvest Festival

Strathcona Harvest Festival

Dean dekes out Kim | Strathcona Soccer Club

Dunlevy Snackbar

McClean Park waterpark

Dunlevy Snackbar

Strathcona

Strathcona | EAST SIDE

Strathcona Harvest

A beautiful vintage Volvo that lives in Strathcona

Along the way, East Side Culture Crawl

Well used pole - East Side Culture Crawl

Along the way, East Side Culture Crawl

House in Strathcona and approaching storm

MacLean Park

Spring in Strathcona

Strathcona 2

S for Strathcona

Water Fight, McLean Park, Strathcona

Tracks in summer

Andrea at Harvest Community Foods

Artists live in Strathcona

Adanac Bike Path Building

Adanac Bike Route

Tracks near Casa Gelato

Fancy Shoes from telephone wires

Ribbons Strathcona

Parker Street Studio of Klee Larsen

Strath Laneway

Gailan Ngan, Ceramics Artist, Strathcona

Strath fence in summer

Union Street | Strathcona | Scout Magazine

Strathcona stairway

Outside the Borshch and Bike Sale in Strathcona

Boyd from The Wilder Snail

Strathcona yard decoration

Harvest Community Foods Ramen bowl

Laundry drying old-school in Strathcona

Janet at Benny's

GAILAN NGAN

Ian | Strathcona Harvest Festival

Jonathan | Strathcona Harvest Festival

Katie and Hazel at the Strathcona Harvest Festival

Strathcona Harvest Festival

Pink Grapefruit at Casa Gelato

Strathcona paste-up

Blue Bus, Strathcona

Pies at the Strathcona Harvest Festival

Finch's famed baguette sandwich with pear, blue brie, walnuts, proscuitto sandwich at the original Finch's

Fire hydrant shenanigans in Strathcona

Strathcona