Scorsese’s Netflix Movie Bets Big on the Confessions of a Mafia “Hitman” Who Made It All Up (original) (raw)

The crime scene at Umberto's Clam House in Little Italy, where "Crazy Joe" Gallo was shot and killed, April 7, 1972. Frank Sheeran later claimed he committed the murder. Bettman/Getty Images

The Lies of the Irishman

Netflix and Martin Scorsese are making their biggest bets ever on the confessions of a mafia “hitman.” The guy made it all up.

Assuming you were alive in April 1972 and old enough to cross the street by yourself, you could take credit for the spectacular murder of mobster Crazy Joe Gallo—gunned down during his own birthday party at Umberto’s Clam House in Little Italy—and nobody could prove you didn’t do it.

Of course, anyone who knows anything about New York City organized crime can tell you who was behind it: The murder was payback for an equally brazen shooting—in broad daylight, in midtown Manhattan—of mob boss Joseph A. Colombo Sr. a year earlier, an attack Gallo supposedly ordered (though even that no one can say with absolute certainty, since the shooter was shot dead on the spot). But no one has ever been arrested or charged in Crazy Joe’s killing, and so technically it’s still unsolved.

The same is true about the disappearance, in July 1975, of Teamsters’ union legend Jimmy Hoffa. He had made some lethal enemies in the mob. After serving a prison term, he persisted in trying to regain control of the union even after he was warned, over and over, to back off. The last time anybody saw him, he was standing outside a restaurant in the suburbs of Detroit, waiting to be driven to what he believed would be a peace meeting. The FBI and investigative reporters have devoted decades of effort to solving the mystery, but all we have is guesswork and theories. So if you want to step up now and say you whacked him, be my guest.

That’s the thing about these gangland slayings: When done properly, you’re not supposed to know who did them. They’re planned and carried out to surprise the victim and confound the authorities. Eyewitnesses, if there are any, prove reluctant to speak up. And nobody ever confesses, unless it’s to win easy treatment from law enforcement in exchange for ratting on other, more important mobsters. Those cases often turn into the ultimate public confessional—the as-told-to, every-gory-detail, my-life-in-crime book deal. Followed by—if you’re a really lucky lowlife—the movie version that fixes your place forever in the gangster hall of fame.

Steerforth

And then there’s the strange case of Frank Sheeran.

Only if you had been paying close attention to the exploits of the South Philadelphia mafia back in its glory days (the second half of the 20th century) might you have noticed Sheeran’s existence. Even there he was a second-stringer—a local Teamsters union official, meaning he was completely crooked, who hung around with mobsters, especially Russell Bufalino, a boss from backwater Scranton, Pennsylvania. Sheeran was Irish, which limited any Cosa Nostra career ambitions he might have had, and so he seemed to be just a 6-foot-4, 250-pound gorilla with a dream. He died in obscurity, in a nursing home, in 2003.

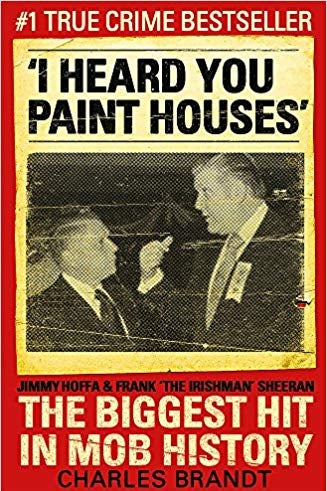

Then, six months later, a small publishing house in Hanover, New Hampshire, unleashed a shocker titled I Heard You Paint Houses. It was written by Charles Brandt, a medical malpractice lawyer who had helped Sheeran win early parole from prison, due to poor health, at age 71. Starting not long after that, Brandt wrote, Sheeran, nearing the end of his life, began confessing incredible secrets he had kept for decades, revealing that—far from being a bit player—he was actually the unseen figure behind some of the biggest mafia murders of all time.

Frank Sheeran said he killed Jimmy Hoffa.

He said he killed Joey Gallo, too.

And he said he did some other really bad things nearly as incredible.

Most amazingly, Sheeran did all that without ever being arrested, charged, or even suspected of those crimes by any law enforcement agency, even though officials were presumably watching him for most of his adult life. To call him the Forrest Gump of organized crime scarcely does him justice. In all the history of the mafia in America or anywhere else, really, nobody even comes close.

Now, though, Frank Sheeran is finally going to get his due.

When it premieres at the New York Film Festival in September before a fall release, The Irishman (as the tale has been retitled) will immediately enter mob movie Valhalla: Martin Scorsese directing, Robert De Niro as Sheeran, Al Pacino as Hoffa, and Joe Pesci as Bufalino, all together for the first (and probably last) time. Sheeran is a part that De Niro has reportedly wanted to play since Brandt’s book came to his attention over a decade ago. The actor has been nursing it along ever since, finally getting Netflix to put up a reported $160 million. This will be Scorsese’s most expensive film ever, in part because of the extensive digital manipulation required to allow De Niro, who turns 76 this month, to play Sheeran from his prime hoodlum years until his death at age 83.

All in all, an astounding saga. Almost too good to be true.

No, let’s say it: too good to be true.

“I’m telling you, he’s full of shit!” This is a retired contemporary of Sheeran’s, a fellow Irishman from Philadelphia named John Carlyle Berkery, who allegedly headed the city’s Irish mob for 20 years and had many close mafia connections. Berkery is a local legend, one of the few figures of that era still alive, not incarcerated, and in full possession of his wits. “Frank Sheeran never killed a fly,” he says. “The only things he ever killed were countless jugs of red wine. You could tell how drunk he was by the color of his teeth: pink, just started; dark purple, stiff.”

“It’s baloney, beyond belief,” agrees John Tamm, a former FBI agent on the Philadelphia field office’s labor squad who investigated Sheeran and once arrested him. “Frank Sheeran was a full-time criminal, but I don’t know of anybody he personally ever killed, no.”

Not a single person I spoke with who knew Sheeran from Philly—and I interviewed cops and criminals and prosecutors and reporters—could remember even a suspicion that he had ever killed anyone.

Frank “the Irishman” Sheeran, circa 1970; Robert De Niro as Frank Sheeran. Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photos by Sheeran/Brandt/Splash, Netflix.

Certainly, his first noteworthy mischief held no promise of underworld greatness. In 1964, at the somewhat advanced age of 43, Sheeran was charged with beating a non-union truck driver with a lug wrench—about what you’d expect from a Teamster goon. Sheeran was later twice indicted in the murders of union rivals. But in neither case did the government or anyone else accuse him of touching a trigger, only of hiring the hit men who did his dirty work for him. When Sheeran was finally convicted of something, it was for cheating his own union members. Not exactly the kind of crime that gets you invited to Don Corleone’s daughter’s wedding.

But none of Sheeran’s nonlethal past mattered or even came up once the book came out. Though Publishers Weekly called it “long on sensational claims and short on credibility,” the credulous world welcomed a solution to the mystery of Jimmy Hoffa’s whereabouts and a chance to read tales of other famous mobster mayhem. Even the New York Times’ reviewer wrote, “It promises to clear up the mystery of Hoffa’s demise, and appears to do so.” The book appeared on the Times’ extended bestseller list and has sold over 185,000 copies, according to its publisher. Charles Brandt, the former chief deputy attorney general of the state of Delaware, was, at 62, the author of a hot property.

Let’s start by looking at Sheeran’s most explosive claim, of having shot his friend Jimmy Hoffa.

Here’s the version of that mystery that has, over the years, gained the most traction: Not only was Hoffa—against the mob’s wishes—intent on regaining control of the Teamsters upon his release from prison (for jury tampering), but he was also feuding with mafioso Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano, head of the Teamsters local based in Union City, New Jersey. With the assistance of the Detroit mob, Provenzano hatched a plot where a fake meeting would be arranged and a car driven by a Hoffa ally would deliver the victim to his killer, Provenzano’s top enforcer, Salvatore “Sally Bugs” Briguglio. Because Sheeran and Hoffa were close friends as well as union brothers, Sheeran was recruited to ride along in the car to calm any worries Hoffa might have had about getting in.

And here’s Frank Sheeran’s version: In consultation with his fellow mob bosses, Sheeran’s patron Russell Bufalino set up the killing for when he and Sheeran would be in Detroit to attend a wedding. Sheeran rode with the driver when they picked Hoffa up outside the Machus Red Fox restaurant and traveled to an empty house, where the bogus peace meeting was to take place. There, Hoffa jumped out of the car and walked toward the front door with Sheeran on his heels. They entered the vestibule, Hoffa saw there was no one inside, and realized he had walked into a trap. Sheeran, standing right behind him, pulled out his gun.

“If he saw the piece in my hand he had to think I had it out to protect him,” Sheeran said in the book. “He took a quick step to go around me and get to the door. He reached for the knob and Jimmy Hoffa got shot twice at a decent range—not too close or the paint splatters back at you—in the back of the head behind his right ear.”

At which point Sheeran exits the scene and a cleanup crew takes over.

Now then: Who buys Frank Sheeran’s story?

Does the FBI buy it?

According to Brandt, Robert Garrity, the FBI agent who led the investigation into Hoffa’s disappearance, once told him, “We always liked Sheeran for it.” But when I emailed Garrity to verify that, he wrote back: “I have no interest in talking about that book for a number of reasons which are personal. Good luck with your article.”

Jimmy Hoffa in 1974; Al Pacino as Jimmy Hoffa. Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photos by Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images, Netflix.

We can, however, read Garrity’s original conclusions in something called “the Hoffex memo,” a 57-page summary of the investigation drafted in January 1976. The document lists a dozen men who were suspected of having some involvement in either killing Hoffa or disposing of his remains. Here’s what the memo said about Sheeran: “Known to be in Detroit area at the time of [Hoffa’s] disappearance, and considered to be a close friend” of Hoffa’s.

Which suggests that Sheeran might have been part of the plot to kill Hoffa. But it was Briguglio, according to the memo, who was “involved in actual disappearance” of Jimmy Hoffa.

Does Steven Brill buy Sheeran’s story?

Brill is the author of The Teamsters, a history of the union and Hoffa’s disappearance, published in 1978. “When the book came out,” Brill says, “I had vaguely mentioned Sheeran as someone who might have been partially involved in Hoffa’s abduction. As a bit player.”

But Brandt’s book says Brill was reported to have interviewed Sheeran and had him—on tape—confessing to the murder.

“Total bullshit,” Brill says. “I would love to have had that. But I never talked to him.”

Does Ronald Cole buy Sheeran’s story?

Cole was a lawyer with the U.S. Department of Justice’s Organized Crime and Racketeering Strike Force in Philadelphia, which brought union boss Sheeran into his sights. He’s the prosecutor who finally put Sheeran behind bars for making sweetheart deals with businesses that employed Teamsters.

“I remember when the book came out,” Cole says, “I asked the FBI agents if they gave any credence to it, and they all told me, ‘No!’ ”

Does Selwyn Raab buy Sheeran’s story?

Raab is a veteran journalist, a reporter at the New York Times for 26 years, and the author of Mob Lawyer about Frank Ragano, who represented, among other gangster legends, Jimmy Hoffa.

“I know Sheeran didn’t kill Hoffa,” Raab says. “I’m as confident about that as you can be. There are 14 people who claim to have killed Hoffa. There’s an inexhaustible supply of them.”

Does Dan Moldea buy Sheeran’s story?

“I play second banana to no one” on this story, he says, and it’s easy to see why—he’s the author of nine books of investigative journalism, but is still best known for 1978’s The Hoffa Wars, which he began researching before its subject vanished. Between working on that book and on his website, he has spent more than 40 years on the Teamster trail, chasing down every shred of evidence and rumor about Hoffa’s disappearance and disposal.

Sheeran “was definitely involved,” Moldea says, “but he confessed to a murder he didn’t commit. Truthfully, I’m upset because I spent my entire career investigating this case, interviewed over 1,000 people, and I have a legitimate claim to having made an important contribution. And then a guy who wrote a one-source book based on the word of a convicted felon and proven liar gets everything? The bestselling book, the movie star treatment that comes to very few but is what every author wants? Yes, I’m bitter about this.”

Even Sheeran, before he said that he killed Hoffa, said that he didn’t. In 1995, he announced to Kitty Caparella, who covered organized crime for the Philadelphia Daily News, that he was negotiating a multimillion-dollar deal for a book he would write with a collaborator he met in prison. “I did not kill Hoffa and I had nothing to do with it,” Sheeran told her, and then he named the real mastermind behind the disappearance: President Richard Nixon.

Before we go any further, a brief but possibly relevant digression about the “paint splatters” Sheeran mentioned in his account of Hoffa’s killing. According to Sheeran, the first time he and Hoffa ever talked was on the phone, in a conversation that Hoffa started by saying, “I heard you paint houses.” Also according to Sheeran, those words were mob code meaning: I heard you kill people, the “paint” being the blood that splashes when you fire bullets into a body.

To which Sheeran replied, “Yeah, and I do my own carpentry work, too.” Meaning: I also dispose of the dead bodies.

Here’s my nagging question: In all of mob literature, fictional and factual, has anyone ever uttered such expressions about painting and carpentry? I couldn’t find any. Nobody I interviewed—and they number in the dozens, good guys, bad guys, neutral observers—had ever heard it either. Go Google it yourself and email me if you find it anywhere except in Frank Sheeran’s mouth. Even Charles Brandt admits he had never heard of it, but added that mobsters in Bufalino’s isolated corner of northeastern Pennsylvania “have their own lingo.”

I don’t want to slow things down any further by pointing out that Sheeran was from Philly and Hoffa from Detroit.

Anyway, it’s a vivid and memorable title. It was chosen by Frank Weimann, the literary agent who sold the book.

Brandt says that when Hoffa made that fateful phone call, he was looking for someone who would kill union rivals and other foes for him. Sheeran claimed he took the job. Brandt told me, “Frank confessed to 25 to 30 murders, he couldn’t remember how many. One day he did a tour for Hoffa—he flew to Chicago and then to Puerto Rico and did a total of three hits.”

And there we have just one more astounding piece of Sheeran’s tale: so many murders he lost count! Except there’s no evidence that even one such killing ever took place. No one (aside from Frank Sheeran) has ever alleged that Hoffa commissioned even a single murder. When you ask Brandt for proof, he can only point to times that Hoffa—who was a famous hothead and raging blowhard—said he wanted to kill a long list of people, including John Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy, and others who crossed him. No known murders, though.

And back to the action.

Here is the version of Joey Gallo’s killing as it has come to be accepted over the years: He was out on the town with friends, family, his new wife, and her daughter to celebrate his 43rd birthday. First, the party visited the Copacabana nightclub, and then, in the wee hours, decided to eat. They couldn’t find an open restaurant in Chinatown so they wandered into Little Italy to a new joint, Umberto’s Clam House, not knowing it was owned by a mobster named Matty the Horse.

As they entered, a hood who was connected to the Colombo family saw them and immediately split, found some colleagues, and told them he had spotted Gallo. They called their boss, who told them to arm themselves, drive over to Umberto’s, and kill him. They followed orders, burst into the restaurant, and one of them—a convicted murderer named Carmine “Sonny Pinto” Di Biase—began blasting. Gallo was hit three times. Killers and victim then made their way outside, where the murder crew piled into cars and took off and left Gallo in the street, dying.

Umberto’s Clam House after Gallo’s murder, 1972; a still from _The Irishman_’s trailer, showing the moment before the crime. Photo illustration by Lisa Larson-Walker. Photos by Jim Heimann Collection/Getty Images, Netflix.

And here’s Sheeran’s version: Gallo’s murder happened not due to his war with the Colombo family but because, earlier in the evening at the Copa, Crazy Joe was rude to Sheeran’s boss Russell Bufalino, who gave Frank the nod. Sheeran says he was informed by spies not only which restaurant Gallo would choose hours later, but exactly where he would be sitting. Sheeran arrived at the appointed time and entered alone, trying to seem like a working truck driver needing a break.

Then, once inside:

A split second after I turned to face the table, Crazy Joey Gallo’s driver got shot from behind. … Crazy Joey swung around out of his chair and headed down toward the corner door to the shooter’s right. … It was easy to cut him off by going straight down the bar to the door and getting right behind him. He made it through Umberto’s corner door to the outside. Crazy Joey got shot about three times outside of the restaurant not far from the corner door.

OK, who buys Sheeran’s story?

Did the police buy it?

Hard to say, since the detectives in charge of the case are dead. But newspaper coverage of the killing all carried a description of the gunman offered by police and witnesses—according to the New York Daily News he was “about 5-foot-8, stocky, about 40 years old and with receding dark hair.” In other words, not Sheeran but Di Biase.

Does Frank Storey buy Sheeran’s story?

Storey was the FBI assistant special agent in charge of the organized crime program at the New York City field office. “That’s just crazy,” he says. “He didn’t do it. He never would have gone to New York to do that. It just wouldn’t have happened.”

Does Sina Essary buy Sheeran’s story?

Essary was sitting at the table at Umberto’s with her new husband Joey Gallo, her 10-year-old daughter, and the others in their party when the bullets began to fly. “They were little, short, fat Italians,” she says of the hit squad, hardly describing a 6-foot-4 Irishman.

Does Nicholas Gage buy Sheeran’s story?

Gage was the New York Times reporter who broke the inside story of Gallo’s killing, including who did it, how, and why. He had been covering the mob for the Times and the Wall Street Journal for years and wrote The Mafia is Not an Equal Opportunity Employer, a 1971 book that focused partly on Gallo. (They met not long before the murder.) Gage interviewed Joseph Luparelli, the wiseguy who spied Gallo at Umberto’s and set in motion the events that led to the killing. Then, in 1975, Gage spent three days interviewing Gallo’s bodyguard, Pete “the Greek” Diapoulas, who was shot once, and who told the same story—including identifying Di Biase, whom he knew, as the shooter.

“I haven’t read the script of The Irishman,” Gage says, “but the book on which it is based is the most fabricated mafia tale since the fake autobiography of Lucky Luciano 40 years ago.”

Before we go any further, another quick digression about something you may have noticed earlier—the weird way that Sheeran phrased his confessions to both murders. Specifically, his use of the passive voice. “Jimmy Hoffa got shot twice at a decent range.” “Crazy Joey got shot about three times outside of the restaurant.”

I wondered about that, too.

Near the end of the book, Brandt tries to get Sheeran to confirm, one final time, all that he confessed before.

“Now,” Brandt said to Sheeran, “you read the book. The things that are in there about Jimmy and what happened to him are things that you told me, isn’t that right?”

Frank Sheeran said, “That’s right.”

“And you stand behind them?”

And he said, “I stand behind what’s written.”

Which means that even in his deathbed confession, Frank Sheeran never actually says the words, “I killed Jimmy Hoffa,” or that he killed Joey Gallo, or anybody at all.

When I bring this up to Brandt, he scoffs. Had Sheeran made the grammatical misstep of saying plainly “I killed them,” Brandt believes, he would have been making an airtight confession to two murders and exposed himself to guaranteed life in prison.

“If anything,” Brandt says, “it adds to Frank Sheeran’s credibility.”

Sheeran’s claims about killing Gallo and Hoffa aren’t even his most amazing yarns. He also said that just before the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, in 1962, he was ordered by his mob bosses to drive a truckload of uniforms and weapons to a dog track in Florida, where he delivered the cargo to CIA agent E. Howard Hunt, who , a decade later, would be one of the Watergate burglars. And then, in November 1963, Sheeran said he was summoned to an Italian restaurant in Brooklyn, where a gangster handed him a duffel bag containing three rifles and told him to deliver them to a pilot, who took the bag and disappeared—and then, next thing you know, Lee Harvey Oswald assassinated the president. Also, Sheeran tells about taking a suitcase containing half a million dollars in cash to the lobby of the Washington, D.C. Hilton, where he was joined by then–U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell, who sat a while to shoot the breeze and then walked off with the money, a bribe for his boss, President Richard Nixon.

I could keep going like this, but you get the picture. It’s time, at last, to ask: Does anybody buy Frank Sheeran’s story?

I found four such individuals.

Chip Fleischer buys it.

Fleischer was the editor at Steerforth Press who bought the book and guided it to publication. “When I read it,” he says, “my reaction was this potentially was the biggest thing we ever published—in terms of sales, but also in terms of historical importance.”

Fleischer knew they would be contradicting widely accepted versions of famous crimes. “I couldn’t help but worry we were going to come out looking silly somehow,” he says, “but just the opposite happened.” Fleischer is now the publisher of Steerforth Press.

Frank Weimann buys it.

Weimann, a veteran New York literary agent who has also represented other successful mob-related books, including memoirs by Joe Bonanno and his son Bill, steered Brandt’s book through two publishing deals that fell apart before the successful third try at Steerforth. One of those attempts was scuttled, Weimann told me, when it was discovered that Sheeran had forged a letter he said Hoffa had written to him.

Brandt writes in the book that despite the forgery, he still believed in Sheeran. What about Weimann? Did the literary agent have any doubts about the truthfulness of the book?

“No,” he says, “I never did.”

Eric Shawn buys it.

Shawn is a Fox News reporter who went to Detroit and found the house where Sheeran said Hoffa was killed, then had the floorboards in the doorway tested for human blood. And found some, he revealed—but none of the DNA matched Hoffa’s (which Shawn says could be attributed to the years that passed between the killing and the testing). In the course of his reporting, Shawn says he interviewed people in Sheeran’s hometown and in Hoffa’s, not one of whom ever suspected a thing. “In Philadelphia they think he was just a drunk. In Detroit they never heard of him,” Shawn says. “So, he’s the perfect guy” to carry out the murders. “He slipped through the cracks.” When a Slate fact-checker followed up with Shawn, he replied that he’s still investigating and added, “My hour and a half documentary, Riddle: The Search for James R. Hoffa is available now on the new streaming service Fox Nation.”

And Charles Brandt buys it.

This was not Brandt’s first experience with hardened criminals or with publishing. In the Delaware attorney general’s office, he says, he specialized in homicide prosecutions and was an expert in the art of questioning bad people to learn the truth. Before working with Sheeran, he had written a novel based on murders he had solved.

At first, Brandt says, Sheeran told him he wanted to do a book proving he was innocent in Hoffa’s disappearance: “But I could tell, this guy has something he wants to get off his chest. Interrogation is a journey.” Sheeran started by admitting that he was there on the scene when Hoffa was killed, Brandt says, but it wasn’t until more than eight years later—when Sheeran realized that he was nearing death—that he finally confessed to shooting his friend and Teamster brother.

Brandt questioned Sheeran over the course of five years, he says, and used every trick he learned as a prosecutor to try and catch Sheeran in a lie. “I knew that everything I ultimately accepted from him was the truth,” Brandt says. Any skepticism about the book “is nonsense.”

After the initial publication of I Heard You Paint Houses, Brandt says, he began receiving independent verifications of Sheeran’s claims from people in a position to know. “It was like stuff was coming out of nowhere to corroborate Frank’s confession,” he says. These accounts appear in the updated edition of the book.

According to Brandt, New York City Detective Joe Coffey, who investigated Gallo’s shooting back in ’72, told him that he “believed it had been solved by Frank’s confession.” But in The Coffey Files, the detective’s own 1992 memoir, he says he learned from informants that Sonny Pinto was the shooter—just as everyone has held all along. We can’t reconcile these; Coffey died in 2015.

The best of Brandt’s verifications came when he discovered an eyewitness to Gallo’s shooting. In the book, she’s anonymous at her request. In 1972 she was a college student visiting New York, Brandt writes, and happened to be at Umberto’s in the wee hours of the night in question. When I spoke with her on the phone, she asked to be identified as someone who has worked as a journalist for New York City newspapers.

When she heard shots, she says, she looked up at where they came from and saw a tall man, “not particularly Irish-looking,” she remembers. “He was ruddy. He was definitely not a short Italian.”

Did she see a gun in his hand? “No—I don’t think so,” she says.

In his book, Brandt says that in 2004, he showed her several photos of Sheeran, at different ages. He writes:

Then she looked again at the photo of Sheeran taken around the time of the Gallo hit, and she said with palpable fear, “This picture gives me chills.”

When I spoke with her, here’s what she said: “As far as corroborating that it was Frank Sheeran, when I was shown three photos, the person I identified looked more like him than anybody else. And this was many, many years afterward.”

Thirty-two years, to be exact. Does she believe he was Gallo’s killer?

“Do I think it was Frank Sheeran? Yeah.”

And that’s it for the real-life version of events. Now we can turn to the movies, where the standard of proof is more relaxed. Martin Scorsese grew up in Little Italy. He has already directed two classic movies about the mob—Goodfellas and _Casino_—based solidly on nonfiction books by a respected journalist, Nicholas Pileggi. So, we know he is somewhat wise in these matters. Yet he’s made a movie based on a book whose central claims are denied by a whole lot of people in a position to know.

It’s possible The Irishman will treat Sheeran’s stories as tall tales. Scorsese, of course, has played with subverting criminals’ self-aggrandizement before; think of Jordan Belfort’s unreliable narration in The Wolf of Wall Street, a movie that makes it clear, by the end, that its protagonist views us, the audience, as just another mark. Is that what Scorsese’s up to with The Irishman? Did Netflix invest nearly $200 million in a scathing satire of gangster braggadocio? Or does he buy Frank Sheeran’s story?

I don’t know. Scorsese declined to talk to me.

I do know about a discussion in 2014 between Robert De Niro and Hoffa expert Dan Moldea, after a writers’ banquet the author hosts annually in Washington. There, Moldea spent 20 minutes lecturing De Niro that his movie would be based on a lie while the actor quietly listened. “De Niro was very polite, and Dan was very forceful,” said Gus Russo, Moldea’s friend and a fellow investigative reporter.

Moldea doesn’t disagree—“I told him, ‘Bob, you’re getting conned.’ ”

“Hollywood gets the last word,” Russo says.

Does De Niro buy Sheeran’s story? I don’t know. He also declined to talk to me.

We’re closing in on the end of this saga, and still have yet to wonder: Why might Frank Sheeran have confessed to such horrible acts if he hadn’t done them? According to Brandt, Sheeran, nearing death, returned to his Catholic faith and wished to clear his conscience, even though it meant admitting that he had killed his best friend. It takes some of the shine off that halo when you remember that he could have spilled his guts while he was still healthy enough for life in prison. Sheeran can’t enjoy any of the financial reward for his confession but his heirs, three of his daughters, can: They and Brandt split all proceeds from the book, including the film rights. Even if that motive for writing the book seems cynical, we’d know that at least once in his life, Sheeran had a selfless impulse.

And so, to sum things up, here’s what “I Heard You Paint Houses” asks us to believe, the story that The Irishman appears ready to tell the world: that starting at age 52, having no known murders on his résumé, Frank Sheeran, a Teamster thug and well-known drunk, was selected to carry out two of the most audacious hits in the history of organized crime, plus a long list of other heinous acts.

On the other hand, here’s what we know for sure: Nobody ever accused Frank Sheeran of killing Jimmy Hoffa—except Frank Sheeran.

Nobody ever accused Frank Sheeran of killing Joey Gallo—except Frank Sheeran.

Nobody ever accused Frank Sheeran of killing 25 to 30 other people, so many he couldn’t remember them all. Except Frank Sheeran.

Now, maybe that means he really was the smartest, sneakiest, stealthiest hit man of all time.

That’s a possibility.

But then you remember that, by and large, mob guys have never been what you’d call geniuses of crime. Oh, they break a lot of laws. They’re superb at that. Still, history has shown that they are not the type to repeatedly break the law unobserved, undetected, unarrested. Eventually they all get caught, most on multiple occasions. They wind up either behind bars, dead, or living under new, government-issued identities.

I spoke of this once with the late journalist Jimmy Breslin, who was among our greatest chroniclers of mob life (and whose comic novel, The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, was inspired by Gallo and his crew).

I asked Breslin: Aren’t gangsters as smart and cunning as they’re depicted in movies and books?

“IQs of 55,” he said. “They all went to jail. What does that tell you? To be charitable, it was an overrated business.”

Anyway, it should be a great movie.