DNSSEC (original) (raw)

DNSSEC is an extension to regular DNS that provides integrity and authentication on all DNS messages sent. Sanity check: Why do we not care about the confidentiality of DNSSEC?1

33.1. Signing records

We want every DNS record to have integrity and authenticity, and we want everyone to be able to verify the integrity and authenticity of records. Digital signatures are a good fit in this situation, because only someone with the private key can create signatures, and everyone can use the public key to verify signatures.

To ensure integrity and authenticity, let’s have every name server generate a public/private key pair and sign every record it sends with its private key. When the name server receives a DNS request, it sends the records, along with a signature on the records and the public key, to the resolver. The resolver uses the public key to verify the signature on the records.

Because of the signatures, a network attacker (MITM, on-path, off-path) cannot tamper with the data or inject malicious data without being detected (integrity). Also, the resolver can cache the signatures and the public key, and check at any time that the records actually came from the name server (authenticity).

You might see a flaw in this design: what if a name server is malicious? Then the malicious name server could return valid signatures on malicious records. How do we modify our design to prevent this?

33.2. Delegating trust

The main issue in our design so far is we lack a trust anchor. We want DNSSEC to defend against malicious name servers, so we cannot implicitly trust the name servers. However, if we don’t trust anybody, then DNSSEC will never work (we’ll never trust any records we get), so we must first choose a trust anchor, an entity that we implicitly trust. In DNSSEC, the root servers are the trust anchor: every computer automatically assumes that the root server is honest and uncompromised. In real life, this is a safe assumption, because the organizations overseeing the Internet hold painstakingly formal ceremonies to ensure that the root server is uncompromised. (If you’re interested, you can read more about the root signing ceremony here.)

Given a trust anchor, we can now delegate trust from the trust anchor to somebody else. If the root endorses Alice, then you can be sure that Alice is trusted as well, since you implicitly trust the root. Also, if Alice endorses Bob, then you can be sure that Bob is trusted, since you trust Alice. This trust delegation starting from the root is how DNSSEC delegates trust from the root to all legitimate name servers, while protecting against malicious name servers.

Consider two parties, root and Alice, who each have a public key and a private key. You trust root, because it is the trust anchor. The root can delegate trust to Alice by signing Alice’s public key. The root’s signature on Alice’s public key effectively says that Alice’s public key is trustworthy, and the root trusts any message signed by Alice using her corresponding private key.

Now, when Alice signs a message, we can use Alice’s public key to verify that the message was properly signed by Alice. Also, we know that Alice’s public key is trusted, because the root has signed it, and we implicitly trust the root.

If Alice was malicious, then the root would not delegate trust to her by signing her public key, because we are trusting that the root is honest and uncompromised.

We can apply this delegation idea to the entire DNS tree. Each name server will sign the public key of all its trusted children name servers. For example, root signs .edu’s public key. We trust root, and root signed .edu’s public key, so now we trust .edu. Next, .edu signs berkeley.edu’s public key. We trust .edu, and .edu signed berkeley.edu’s public key, so now we trust berkeley.edu.

33.3. DNSSEC Intuition

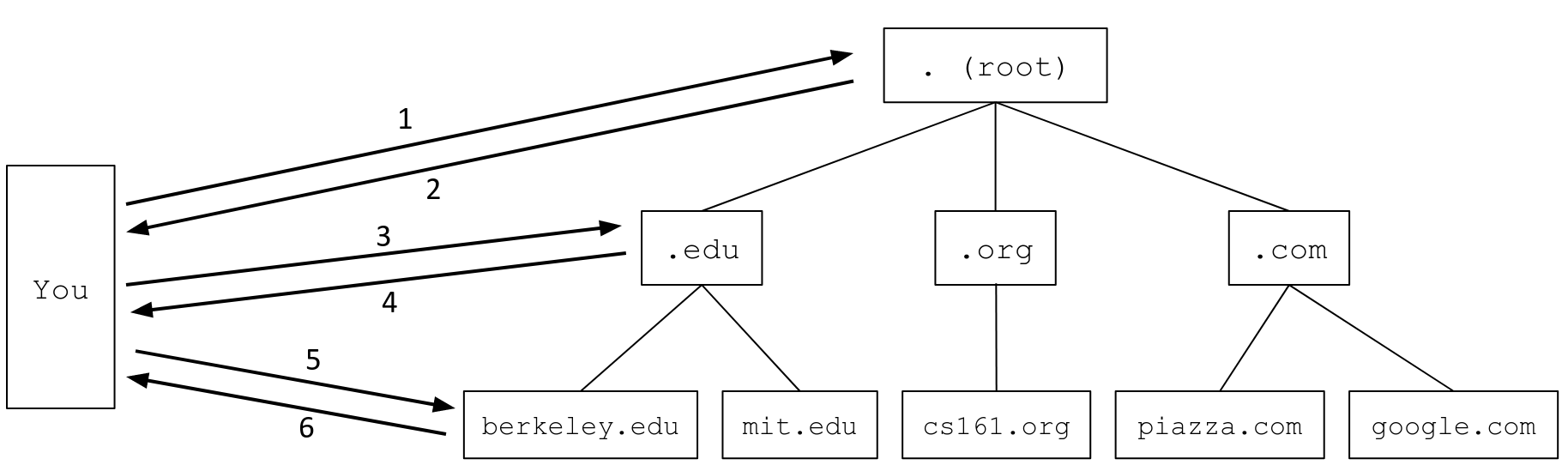

With these ideas in mind, let’s revisit the DNS query for eecs.berkeley.edu from earlier and convert it to a secure DNSSEC query. The DNSSEC additions are italicized.

- You to the root name server: Please tell me the IP address of

eecs.berkeley.edu. - Root server to you: I don’t know, but I can redirect you to another name server with more information. This name server is responsible for the

.eduzone. It has human-readable domain namea.edu-servers.netand IP address192.5.6.30. Here is a signature on the next name server’s public key. If you trust me, then now you trust them too. Finally, here is my public key. - You to the

.eduname server: Please tell me the IP address ofeecs.berkeley.edu. - The

.eduname server to you: I don’t know, but I can redirect you to another name server with more information. This name server is responsible for theberkeley.eduzone. It has human-readable domain nameadns1.berkeley.eduand IP address128.32.136.3. Here is a signature on the next name server’s public key. If you trust me, then now you trust them too. Finally, here is my public key. - You to the

berkeley.eduname server: Please tell me the IP address ofeecs.berkeley.edu. - The

berkeley.eduname server to you: OK, the IP address ofeecs.berkeley.eduis23.185.0.1. Finally, here is my public key and a signature on the answer.

Note that we implicitly trust all signed messages from the root, because the root is our trust anchor. In practice, all DNS resolvers have the root’s public key hardcoded, and any messages verified with that hardcoded key are implicitly trusted.

Congratulations, you now have all the intuition for how DNSSEC works! The rest of this section shows how we implement this design in DNS.

33.4. New DNSSEC record types

To store cryptographic information in DNS messages, we need to introduce a few new record types.

The DNSKEY type record encodes a public key.

The RRSIG type record is a signature on a set of multiple other records in the message, all of the same type. For example, if the authority section returns 13 NS type records, you can sign all 13 records at once with one RRSIG type record. However, to sign the 26 A type records in the additional section, you would need another RRSIG type record. In addition to the actual cryptographic signature, the RRSIG type record contains the type of the records being signed, the signature creation and expiration date, and the identity of the signer (information about which public key/DNSKEY record should be used to verify this signature).

The DS (Delegated Signer) type record is a hash of the signer’s name and a child’s public key. The DS record, combined with a RRSIG record that signs the DS record, effectively allows each name server to sign the public key of its trusted children.

All DNSSEC cryptographic records additionally include some (uninteresting) metadata, such as which algorithm was used for signing/verifying/hashing.

You might have noticed that the number of additional records is always 1 more than the actual number of additional records that appear in the response. For example, consider the final query in our regular DNS query walkthrough:

$ dig +norecurse eecs.berkeley.edu @128.32.136.3

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 52788

;; flags: qr aa; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 1, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;eecs.berkeley.edu. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

eecs.berkeley.edu. 86400 IN A 23.185.0.1

The response reports 1 additional record but shows no additional records at all. This extra record corresponds to the OPT pseudosection (seen just above the question section). This pseudosection allows extra space for DNSSEC-specific flags (e.g. the DO flag requests DNSSEC information), but in order to be backwards-compatible with regular DNS, the section is encoded as an additional record when sent in the request and the reply.

33.5. Key Signing Keys and Zone Signing Keys

There is one final complication in DNSSEC–what if a name server wants to change its key pair? A key change is necessary if, for example, an attacker steals the private key of a trusted name server, because now the attacker can impersonate a trusted name server.

In our current DNSSEC design, a name server that wants to change keys must notify its parent name server so that the parent can change the DS record (which endorses the child’s public key). As it turns out, this process is difficult to perform securely and can easily go wrong.

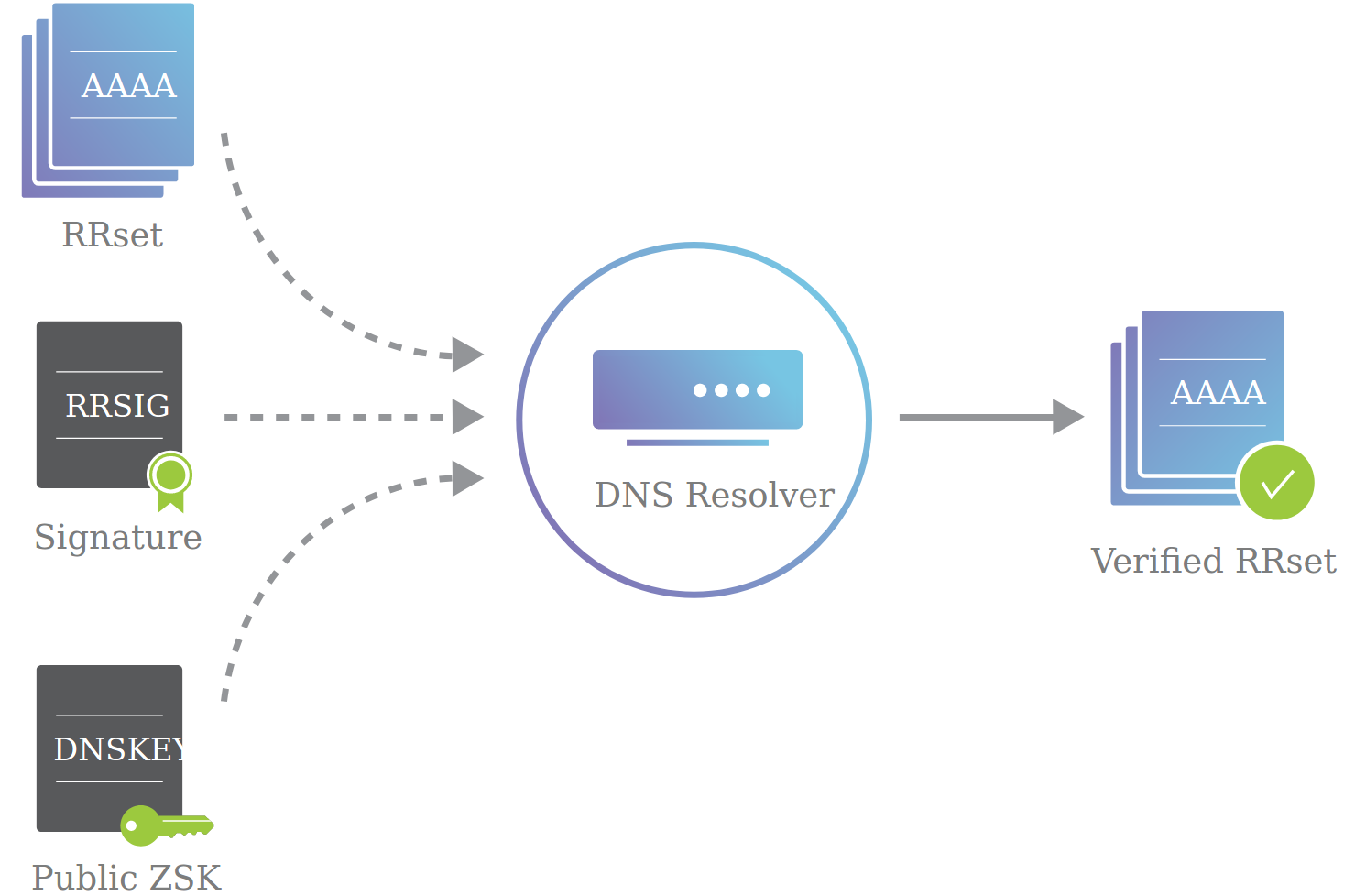

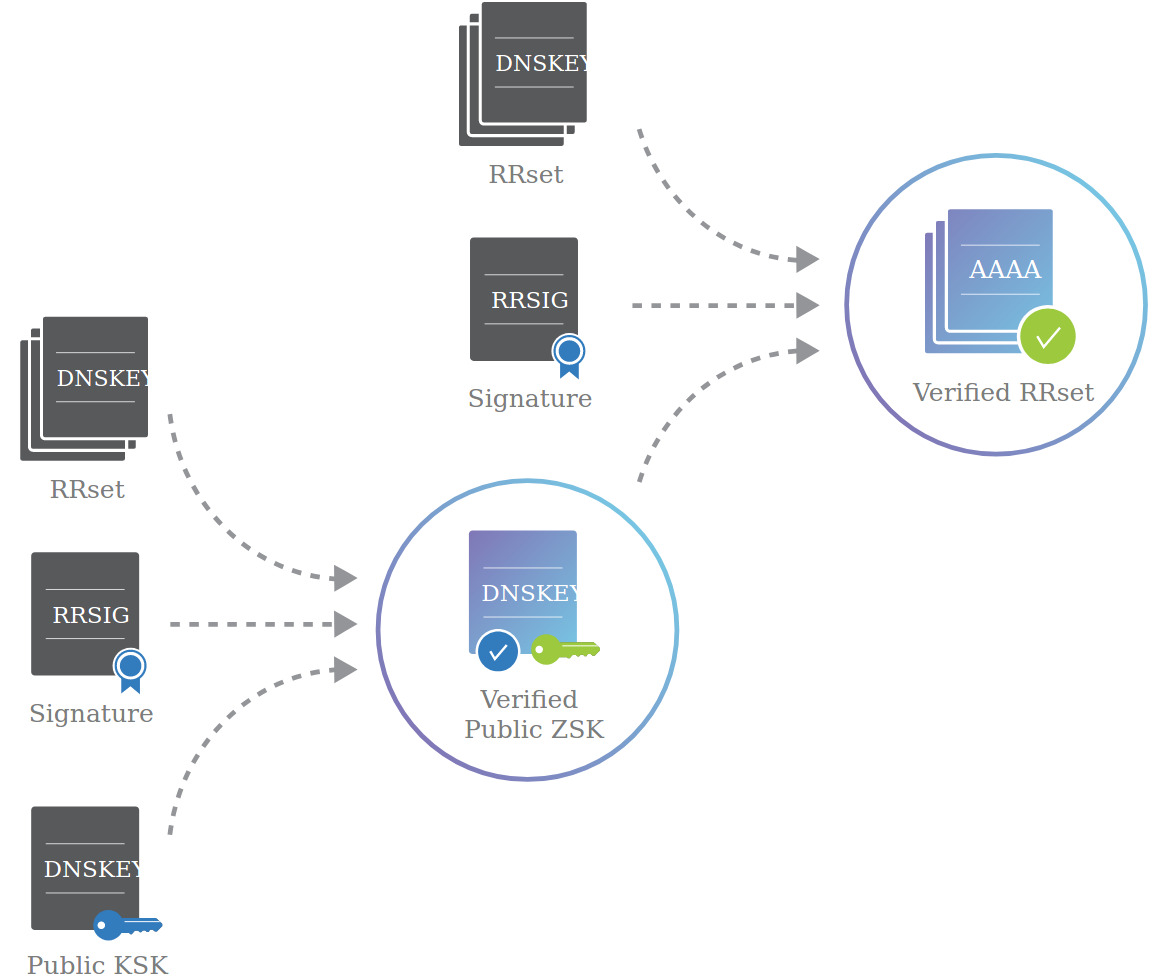

To minimize the use of this difficult key change protocol, each DNSSEC name server generates two public/private key pairs. The key signing key (KSK) is only used to sign the zone signing key, and the zone signing key (ZSK) is used to sign everything else.

In our previous design with one key pair, the name server sends (1) a set of records, (2) a signature on those records, and (3) the public key (endorsed by the parent). The DNS resolver uses the public key to verify the signature, and accepts the set of records.

In our new design with two key pairs, the name server sends (1) the public ZSK, (2) a signature on the public ZSK, and (3) the public KSK (endorsed by the parent). The DNS resolver uses the public KSK to verify the signature, and accepts the public ZSK. Note that this is the exact same structure that was used to sign records before, but in this case, the record is the public ZSK, signed using the KSK.

Another way to think about this step is to recall that a parent endorses a child by signing its public key. You can think of the KSK as the “parent” and the ZSK as the “child,” both within one name server. The parent (KSK) endorses the child (ZSK) by signing the public ZSK.

The result of this first step is that we now have a trusted public ZSK. The second step is the same as before: the name server sends a set of records, a signature on those records (using the private ZSK), and the public ZSK (endorsed by the KSK in the previous step).

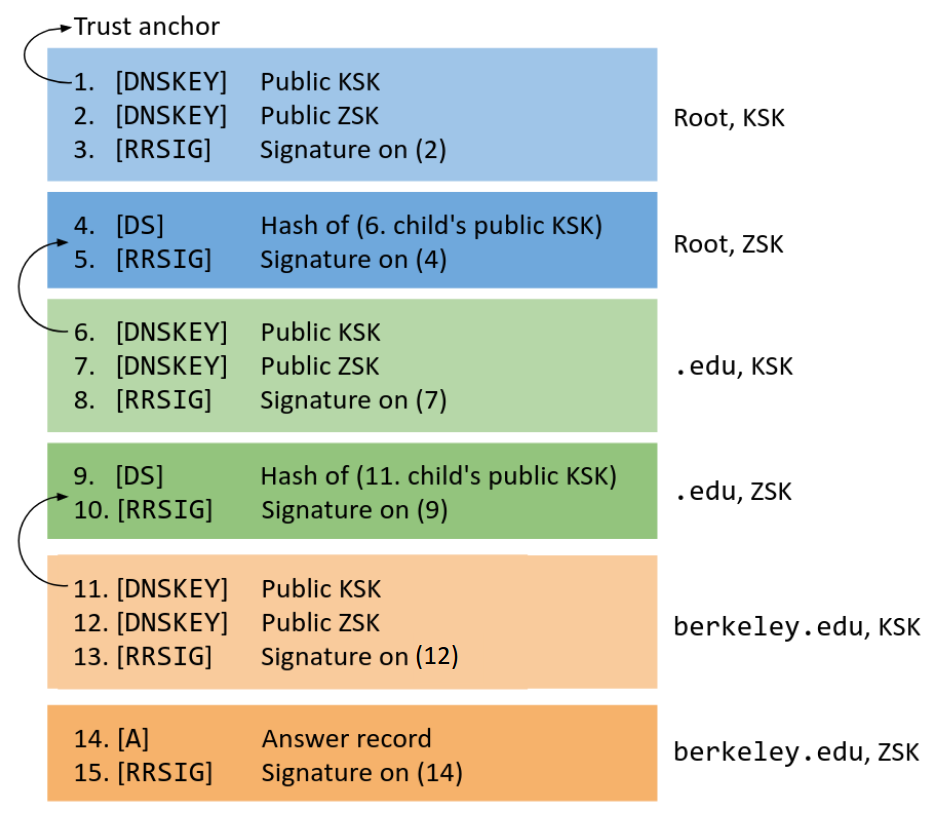

Here is a diagram of the entire two-key DNSSEC. Each color (blue, green, orange) represents a name server. The lighter shade represents records signed with the KSK. The darker shade represents records signed with the ZSK.

Verification would proceed as follows.

- Light blue: Because of our trust anchor, we trust the KSK of the root (1). The root’s KSK signs its ZSK, so now we trust the root’s ZSK (2-3).

- Dark blue: We trust the root’s ZSK. The root’s ZSK signs

.edu’s KSK (4-5), so now we trust.edu’s KSK. - Light green: We trust the

.edu’s KSK (6)..edu’s KSK signs.edu’s ZSK, so now we trust.edu’s ZSK (7-8). - Dark green: We trust

.edu’s ZSK..edu’s ZSK signsberkeley.edu’s KSK (9-10), so now we trustberkeley.edu’s KSK. - Light orange: We trust the

berkeley.edu’s KSK (11).berkeley.edu’s KSK signsberkeley.edu’s ZSK, so now we trustberkeley.edu’s ZSK (12-13). - Dark orange: We trust

berkeley.edu’s ZSK.berkeley.edu’s ZSK signs the final answer record (14-15), so now we trust the final answer.

33.6. DNSSEC query walkthrough

Now we’re ready to see a full DNSSEC query in action. As before, you can try this at home with the dig utility–remember to set the +norecurse flag so you can unravel the recursion yourself, and remember to set the +dnssec flag to enable DNSSEC.

First, we query the root server for its public keys. Recall that the root’s IP address, 198.41.0.4, is publicly-known and hardcoded.

$ dig +norecurse +dnssec DNSKEY . @198.41.0.4

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 7149

;; flags: qr aa; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 3, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags: do; udp: 1472

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;. IN DNSKEY

;; ANSWER SECTION:

. 172800 IN DNSKEY 256 {ZSK of root}

. 172800 IN DNSKEY 257 {KSK of root}

. 172800 IN RRSIG DNSKEY {signature on DNSKEY records}

...

In this response, the root has returned its public ZSK, public KSK, and a RRSIG type record over the two DNSKEY type records. We can use the public KSK to verify the signature on the public ZSK.

Because we implicitly trust the root’s KSK (trust anchor), and the root’s KSK signs its ZSK, we now trust the root’s ZSK.

Next, we query the root server for the IP address of eecs.berkeley.edu.

$ dig +norecurse +dnssec eecs.berkeley.edu @198.41.0.4

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 5232

;; flags: qr; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 0, AUTHORITY: 15, ADDITIONAL: 27

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags: do; udp: 4096

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;eecs.berkeley.edu. IN A

;; AUTHORITY SECTION:

edu. 172800 IN NS a.edu-servers.net.

edu. 172800 IN NS b.edu-servers.net.

edu. 172800 IN NS c.edu-servers.net.

...

edu. 86400 IN DS {hash of .edu's KSK}

edu. 86400 IN RRSIG DS {signature on DS record}

;; ADDITIONAL SECTION:

a.edu-servers.net. 172800 IN A 192.5.6.30

b.edu-servers.net. 172800 IN A 192.33.14.30

c.edu-servers.net. 172800 IN A 192.26.92.30

...

DNSSEC doesn’t remove any records compared to regular DNS–the question, answer (blank here), authority, and additional sections all contain the same records from regular DNS. However, DNSSEC adds a DS record and a RRSIG signature record on the DS record. Together, these two records sign the KSK of the .edu name server with the root’s ZSK. Since we trust the root’s ZSK (from the previous step), now we trust the .edu name server’s KSK.

Next, we query the .edu name server for its public keys.

$ dig +norecurse +dnssec DNSKEY edu. @192.5.6.30

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 9776

;; flags: qr aa; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 3, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags: do; udp: 4096

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;edu. IN DNSKEY

;; ANSWER SECTION:

edu. 86400 IN DNSKEY 256 {ZSK of .edu}

edu. 86400 IN DNSKEY 257 {KSK of .edu}

edu. 86400 IN RRSIG DNSKEY {signature on DNSKEY records}

...

In this response, the .edu name server has returned its public ZSK, public KSK, and a RRSIG type record over the two DNSKEY type records. We can use the public KSK to verify the signature on the public ZSK.

Because we trust the .edu name server’s KSK (from the previous step), and the .edu KSK signs its ZSK, we now trust the .edu name server’s ZSK.

Next, we query the .edu name server for the IP address of eecs.berkeley.edu.

$ dig +norecurse +dnssec eecs.berkeley.edu @192.5.6.30

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 60799

;; flags: qr; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 0, AUTHORITY: 5, ADDITIONAL: 5

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags: do; udp: 4096

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;eecs.berkeley.edu. IN A

;; AUTHORITY SECTION:

berkeley.edu. 172800 IN NS adns1.berkeley.edu.

berkeley.edu. 172800 IN NS adns2.berkeley.edu.

berkeley.edu. 172800 IN NS adns3.berkeley.edu.

berkeley.edu. 86400 IN DS {hash of berkeley.edu's KSK}

berkeley.edu. 86400 IN RRSIG DS {signature on DS record}

;; ADDITIONAL SECTION:

adns1.berkeley.edu. 172800 IN A 128.32.136.3

adns2.berkeley.edu. 172800 IN A 128.32.136.14

adns3.berkeley.edu. 172800 IN A 192.107.102.142

...

In this response, the .edu name server returns NS and A type records that tell us what name server to query next, just like in regular DNS.

In addition, the response has a DS type record and an RRSIG signature on the DS record. Sanity check: which key is used to sign the DS record?2 Together, these two records sign the KSK of the berkeley.edu name server. Because we trust the .edu name server’s ZSK (from the previous step), and the .edu ZSK signs the berkeley.edu KSK, we now trust the berkeley.edu name server’s KSK.

Next, we query the berkeley.edu name server for its public keys.

$ dig +norecurse +dnssec DNSKEY berkeley.edu @128.32.136.3

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 4169

;; flags: qr aa; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 5, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags: do; udp: 1220

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;berkeley.edu. IN DNSKEY

;; ANSWER SECTION:

berkeley.edu. 172800 IN DNSKEY 256 {ZSK of berkeley.edu}

berkeley.edu. 172800 IN DNSKEY 257 {KSK of berkeley.edu}

berkeley.edu. 172800 IN RRSIG DNSKEY {signature on DNSKEY records}

...

In this response, the berkeley.edu name server has returned its public ZSK, public KSK, and a RRSIG type record over the two DNSKEY type records. We can use the public KSK to verify the signature on the public ZSK.

Because we trust the berkeley.edu name server’s KSK (from the previous step), and the berkeley.edu KSK signs its ZSK, we now trust the berkeley.edu name server’s ZSK.

Finally, we query the berkeley.edu name server for the IP address of eecs.berkeley.edu.

$ dig +norecurse +dnssec eecs.berkeley.edu @128.32.136.3

;; Got answer:

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: NOERROR, id: 21205

;; flags: qr aa; QUERY: 1, ANSWER: 2, AUTHORITY: 0, ADDITIONAL: 1

;; OPT PSEUDOSECTION:

; EDNS: version: 0, flags: do; udp: 1220

;; QUESTION SECTION:

;eecs.berkeley.edu. IN A

;; ANSWER SECTION:

eecs.berkeley.edu. 86400 IN A 23.185.0.1

eecs.berkeley.edu. 86400 IN RRSIG A {signature on A record}

This response has the final answer A type record and a signature on the final answer. Because we trust the berkeley.edu name server’s ZSK (from the previous part), we also trust the final answer.

33.7. Nonexistent domains

Remember that DNS is designed to be fast and lightweight. However, public-key cryptography is slow, because it requires math. As a result, name servers that support DNSSEC sign records _offline_–records are signed ahead of time, and the signatures saved in the server along with the records. When the server receives a DNS query, it can immediately return the saved signature without computing it.

Offline signing works fine for existing domains, but what if we receive a request for a nonexistent domain? There are infinitely many nonexistent domains, so we cannot sign them all offline. However, we cannot sign requests for nonexistent domains online either, because this is too slow. Also, online cryptography makes name servers vulnerable to an attack. Sanity check: what’s the attack?3

DNSSEC has a clever solution to this problem–instead of signing individual nonexistent domains, name servers pre-compute signatures on ranges of nonexistent domains. Suppose we have a website with three subdomains:

b.example.com

l.example.com

q.example.com

If we sort every possible subdomain alphabetically, there are three ranges of nonexistent domains: everything between b and l, l and q, and q and b (wrapping around from z to a).

Now, if someone queries for c.example.com, instead of signing a message proving the nonexistence of that specific domain, the name server returns a NSEC record saying, “No domains exist between b.example.com and l.example.com. Signed, name server.”

NSEC records have a slight vulnerability - notice that every time we query for a nonexistent domain, we can discover two valid domains that we might have otherwise not known. By traversing the alphabet, an attacker can now learn the names of every subdomain of the website:

- Query

c.example.com. Receive NSEC saying nothing exists betweenbandl. Attacker now knowsbandlexist. - Query

m.example.com. Receive NSEC saying nothing exists betweenlandq. Attacker now knowsqexists. - Query

r.example.com. Receive NSEC saying nothing exists betweenqandb. Attacker has already seenb, so they know they have walked the entire alphabet successfully.

Some argue that this is not really a vulnerability, because hiding a domain name like admin.example.com is relying on security through obscurity. Nevertheless, an attempt to fix this was implemented as NSEC3, which simply uses the hashes of every domain name instead of the actual domain name.

372fbe338b9f3bb6f857352bc4c6a49721d6066f (l.example.com)

6898bc7daf3054daae05e8763153ee1506e809d5 (q.example.com)

f96a6ec2fb6efbe43002f4cbf124f90879424d79 (b.example.com)

The order of the domain names has changed, but the process is the same - if someone queries for c.example.com, which hashes to 8dca64e4b6e1724f0d84c5c25c9354d5529ab0a2, the NSEC3 record will say, “No domains exist that hash to values between 6898b... and f96a6.... Signed, name server.”

Of course, an attacker could buy a GPU and precompute hashes to learn domain names anyway… and NSEC5 was born. Fortunately, it’s still out of scope for this class.