Falklands ‘wolf’ that baffled Darwin was actually more like a jackal – new study (original) (raw)

When Charles Darwin stopped briefly at the Falkland Islands on the famous voyage of the Beagle, he ran into one of the great mysteries in animal evolution. The islands had just one native terrestrial mammal, which he confusingly described as a “wolf-like fox”. It wasn’t clear what the species was descended from, or how it had ended up in such a remote place, hundreds of kilometres from the nearest mainland.

The Falkland Islands wolf, known also as the warrah or Dusicyon australis, was hunted to extinction in the latter half of the 19th century. As such it was little studied. Darwin’s visit, in the species’ final decades, remains one of the only scientific observations of this poor animal.

Scientists long thought that the extinct Falklands wolf was, as its name suggests, similar to a wolf. However, new research by colleagues and me published in the journal Mammal Review reveals that, in terms of skull shape and feeding habits, this mysterious “wolf” was more like a jackal.

Where it came from

The Falklands wolf had previously been linked to wolves, coyotes and domestic dogs, and scientists even named it Canis antarticus. It wasn’t until 2009 that DNA analysis was used to prove its closest living relative is the maned wolf of South America, which is actually neither a wolf nor a fox. Nevertheless, this species of wild canid (the wider dog family) is characterised by unusually tall limbs, which make it very different from the rather sturdy Falklands wolf.

The ‘Antarctic wolf’, 1890. JG Keulemans / BHL, CC BY-NC-SA

So where did the Falklands wolf come from? By looking through the South American fossil record, scientists identified its direct ancestor as an extinct fox known as Dusicyon avus which was once found as far south as Patagonia. A 2013 study found Falklands wolf DNA split from its mainland ancestors about 16,000 years ago – during the last ice age.

At that point, when sea levels were much lower, Patagonia was only separated from the Falklands by a small passage of shallow sea which would have frozen over at times. This meant Dusicyon avus probably walked across an ice bridge to the Falklands, before evolving in complete isolation into the warrah.

From wolf to jackal

Mystery solved. So we now know where the warrah came from, but what was it actually like? I wanted to figure out its ecology, and that meant looking at its bones and comparing them to other canids and what we know about their behaviour.

To do this, I worked with a team of LJMU colleagues, a paleontologist from Argentina, and curators at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London. We dug through the cupboards at the NHM and World Museum Liverpool to build a database of more than 120 digital images of representative skulls of living wild canid species, including rare specimens of Falklands wolf and its ancestor Dusicyon avus.

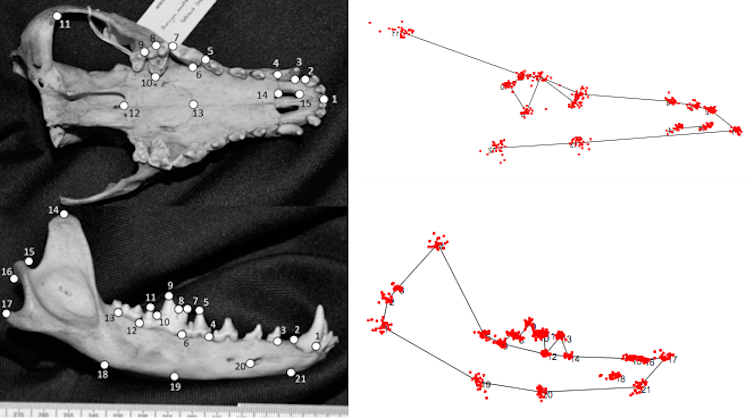

We then mapped out various anatomical landmarks that would be present in each (the tip of the upper and lower jaw, say, or the relative position of upper and lower canines and molar teeth) and used this information to quantify the shape of all the wild canid skulls we investigated. This gave us directly comparable data which helps reveal similarities and differences between species.

Geometric morphology: anatomical landmarks (on the left) are turned into easily-comparable digital images. Meloro et al, Author provided

We realised the Falklands wolf and Dusicyon avus most closely resembled the jackal species found in Africa and Eurasia. Shared features such as wide elongated muzzles, narrow cheekbones, large first lower molars and thick lower jaws, are typical of medium-sized opportunistic predators.

As with jackals alive today, the Falklands wolf would have been an unfussy eater, capable of scavenging or killing everything from small ground-nesting birds to marine mammals like seal pups. Jackal-like feeding habits may even have determined the fate of these “wolves”, as they would also have targeted sheep which were imported to the Falklands from the 1850s onwards.

A seal-eating jackal, Namibia. Mark Caunt / shutterstock

The Falkland Islands wolf is one of many species that, after colonising South America, quickly evolved features similar to distantly-related counterparts in the Old World. The bush dog of South America is another. With its short muzzle and wide cheekbones, this small canid resembles in skull morphology the much larger African hunting dog and the Asiatic dhole. All three species hunt in packs and independently converged on the same head shape, which gives them an unusually strong bite and means they can grab hold of fleeing large prey like deer or capybara.

South America represented an important “laboratory” for the natural selection of modern canid species. The continent now has the world’s richest diversity of dogs, wolves and their relatives. The historical loss of the Falkland Islands wolf highlights, again, that humans are their greatest threat.