The Six-Day Race Part 4: First Six-Day Race (1875) (original) (raw)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 26:02 — 32.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

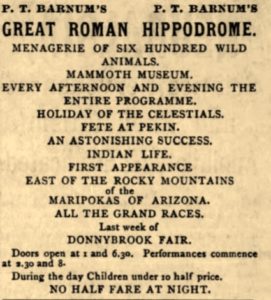

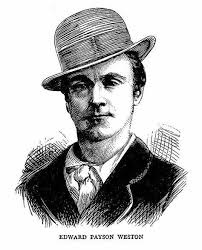

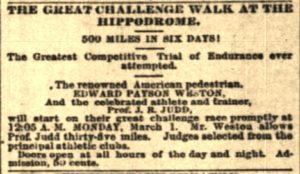

P.T. Barnum featured ultrarunners (pedestrians) in 1874 who were attempting to reach 500 miles in six days, to bring paying patrons into his massive indoor Hippodrome in New York City 24-hours a day. Even though the first attempts by Edward Payson Weston and Edward Mullen came up short (see part 3), America became fascinated by these very unusual efforts of extreme endurance.

P.T. Barnum featured ultrarunners (pedestrians) in 1874 who were attempting to reach 500 miles in six days, to bring paying patrons into his massive indoor Hippodrome in New York City 24-hours a day. Even though the first attempts by Edward Payson Weston and Edward Mullen came up short (see part 3), America became fascinated by these very unusual efforts of extreme endurance.

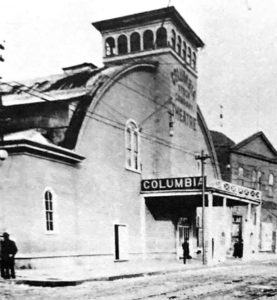

New York Life Building, where the Hippodrome once stood.

But with the failures, critics cried out that it was all just a money grab on the gullible public. It wasn’t a true race. It was said to be similar to watching “a single patient horse attached to a rural cider-press” going in circles for six days until it dropped. Experienced athletes and educated doctors believed that walking or running 500 miles in six days was an impossible feat. P.T. Barnum, “a sucker is born every minute,” did not care what the critics thought, knowing he had a winning spectacle to spotlight. He was right and would put on the first six-day race in history, billed as “the greatest competitive trial of endurance ever attempted.”

Help is needed to support the Ultrarunning History Podcast, website, and Hall of Fame. Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member

P.T. Barnum promotes Professor Judd’s Six-Day Attempt

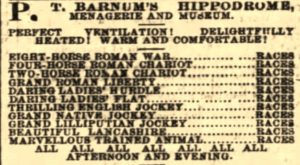

By December 1874, Barnum’s circus was back in full operation in New York in the Hippodrome for the winter season. It was lit by many lanterns, featured chariot races, and presented a menagerie of 600 “wild beasts.”

Barnum turned to a walker other than Weston and hosted “Professor” John R. Judd (1836-1911) at the Hippodrome. Judd had been a gym owner and trainer from Buffalo, New York but recently had moved to New York City. He had gained some fame training boxers and pedestrians and had previously issued a challenge for a walking match against Edward Payson Weston, which was ignored.

Judd’s former hometown wrote, “Judd is excessively muscular. His ‘professorship’ being not anything in the line of learning but simply that of gymnastics.” Another observer wrote, “He is a splendidly formed man, but with a figure better fitted for boxing or wrestling than for walking. He moves heavily and ploddingly, and on account of his great muscular development, he is obliged to keep his whole body in constant motion. He has great powers of endurance but is a slow walker.”

Judd’s true background was suspect. He had been born in England and became very athletic. He claimed to have become a professor of Physical Culture, and trained the Prince of Wales and other royalty. In reality, as noted by those in Buffalo, New York, he was just a gym owner and trainer who liked to do exhibitions of feats of strength. His pedestrian experience was limited. Once he walked 105 miles in four days and claimed to have accomplished other long walks under an alias of John Davison. In 1871, there was a Pedestrian by that name that attempted to walk four days without eating or sleeping at Littlerock Arkansas City Hall.

Judd’s true background was suspect. He had been born in England and became very athletic. He claimed to have become a professor of Physical Culture, and trained the Prince of Wales and other royalty. In reality, as noted by those in Buffalo, New York, he was just a gym owner and trainer who liked to do exhibitions of feats of strength. His pedestrian experience was limited. Once he walked 105 miles in four days and claimed to have accomplished other long walks under an alias of John Davison. In 1871, there was a Pedestrian by that name that attempted to walk four days without eating or sleeping at Littlerock Arkansas City Hall.

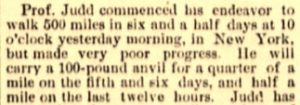

Judd had been announcing that he would do a six and a half day walk in the Empire Skating Rink in New York City. Barnum hired him to instead do it in the Hippodrome. The track was measured carefully the week before the event where Judd put on a five-mile exhibition walk, including walking backwards while carrying an anvil.

Judd had been announcing that he would do a six and a half day walk in the Empire Skating Rink in New York City. Barnum hired him to instead do it in the Hippodrome. The track was measured carefully the week before the event where Judd put on a five-mile exhibition walk, including walking backwards while carrying an anvil.

On December 8, 1874, Judd started his attempt but was said to have made very poor progress on day one. Judd believed in holding a steady pace and could succeed if he walked 77 miles a day. His plans were different than those who tried before him. “He will carry a 100-pound anvil for a quarter of a mile on the fifth and six days and half a mile on the last half day.” On day four he had reached 224 miles when he stopped for lunch which was served on the track. On day five in the morning, Judd had reached 336 miles, and vowed to walk all day and night.

On December 8, 1874, Judd started his attempt but was said to have made very poor progress on day one. Judd believed in holding a steady pace and could succeed if he walked 77 miles a day. His plans were different than those who tried before him. “He will carry a 100-pound anvil for a quarter of a mile on the fifth and six days and half a mile on the last half day.” On day four he had reached 224 miles when he stopped for lunch which was served on the track. On day five in the morning, Judd had reached 336 miles, and vowed to walk all day and night.

By evening of day five, Judd could not continue. “His left knee and his ankles swelled terribly during the day. Toward night he was suffering great pain. He continued to struggle until he had accomplished his 368th mile, when he sank exhausted and was carried to his room. He then claimed that he had sprained his ankle and abandoned the feat. The affair had been a failure, and very few spectators were present during the week.”

Judd’s hometown of Buffalo was disappointed in Judd’s failure and reported that ten days later Judd’s leg was still in “a precarious condition.” They concluded, “The difficulty with Professor Judd was his excessive muscular development, which over-weighed him. Mr. Weston on the contrary is very small and lightly built, having little or no muscle at all.”

Judd would not give up and soon would participate in the first-ever six-day race.

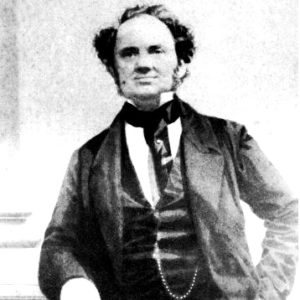

Weston’s Fourth Attempt at 500 Miles in Six Days

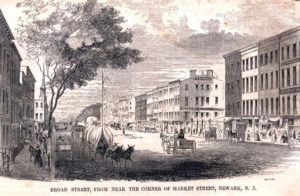

Newark Skating Rink

Weston had failed three times in New York City to walk 500 miles in six days. Because of the poor treatment he had received by the New York City press, he looked elsewhere for this fourth attempt and took his six-day attempt across the Hudson River to the Washington Street skating rink in Newark, New Jersey. Newark put out the welcome mat for him and promised to pay him well. He needed the money to pay off a large mortgage for a huge house that he had recently purchased in Kingsbridge, Bronx, New York.

This attempt was on a very tiny indoor track, sixteen laps to the mile. However, after measuring it closer by civil engineers, it was found to be 24 feet long and lap counters adjusted their distance calculations. Procedures required that every time Weston completed a lap in front of the judges, that the lap number was called off and crossed off the books, “while several others kept separate score sheets to check the record.”

The Start

On the day after Professor Judd failed in his six-day attempt in P.T. Barnum’s Hippodrome in New York City, Weston started his attempt shortly after midnight on December 14, 1874. Weston promised to again reach 115 miles during the first 24 hours. He reached 100 miles in 20:54, obtained 115 miles in 23:02, and then rested for five hours. His moving mile pace on that first day averaged 9:55.

On the day after Professor Judd failed in his six-day attempt in P.T. Barnum’s Hippodrome in New York City, Weston started his attempt shortly after midnight on December 14, 1874. Weston promised to again reach 115 miles during the first 24 hours. He reached 100 miles in 20:54, obtained 115 miles in 23:02, and then rested for five hours. His moving mile pace on that first day averaged 9:55.

To ensure success, Weston wanted to walk huge miles again on day two, but his doctor, Dr. Taylor, convinced him to back off. His walk continued very well, with 75 miles on day two and 80 miles on the third day. He complained bitterly about the small crowds attending and threatened to go to New York City to finish his walk. Some of the leading citizens came and convinced him that they would take care of it, and he continued. The local newspapers quickly published advertisements persuading people to come watch. After day four he had logged, 350 miles. He needed to cover 150 miles during his last two days.

To ensure success, Weston wanted to walk huge miles again on day two, but his doctor, Dr. Taylor, convinced him to back off. His walk continued very well, with 75 miles on day two and 80 miles on the third day. He complained bitterly about the small crowds attending and threatened to go to New York City to finish his walk. Some of the leading citizens came and convinced him that they would take care of it, and he continued. The local newspapers quickly published advertisements persuading people to come watch. After day four he had logged, 350 miles. He needed to cover 150 miles during his last two days.

Dr. Taylor had used an interesting treatment on Weston’s feet to avoid blisters. He “pickled” them prior to the event. “That is, he would let them soak in salt water for a long while at different times, and when resting during the walk he would bathe them in a similar preparation.”

Bribes and Threats

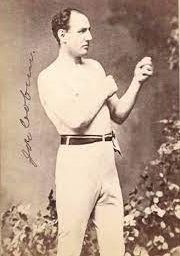

Joe Coburn

After logging another 75 miles on day five, Weston said he was approached by some people offering him thousands of dollars to throw the attempt. He told them to go away but then suspected that other “New York roughs” were plotting to sabotage his remaining effort by throwing pepper and other chemicals at him. The Newark mayor arranged for protection from the police and promised that if the peace could not be preserved, that he would call upon the military.

On the last day, a warrant was issued for the arrest of Joe Coburn (1835-1890) and others for plotting against Weston. Coburn was a prominent boxer. He and his gang had been in trouble with the law before for assault and were involved with gambling. (Two years later, Coburn was arrested in 1877 for the attempted murder of a policeman and served six years in prison). It is possible that all of these gang threats were in Weston’s imagination due to nervousness caused by lack of sleep. The next night he would again express worries that he would be assaulted.

Despite wrenching a hip, Weston pressed on during the last day. The New York Times reported, “There was nothing in his manner to indicate weariness, or a distrust in his ability to finish his walk. His speech was confident and assuring. His gait was steady and unfaltering and his whole person seemed the embodiment of health and power.” During the morning he walked at an even pace, cracked jokes and hummed tunes. When the band arrived in the early afternoon, he pushed hard in spurts and clocked 11-minute miles. It was reported that he had no blisters, chaffing, or swelling of his legs.

Despite wrenching a hip, Weston pressed on during the last day. The New York Times reported, “There was nothing in his manner to indicate weariness, or a distrust in his ability to finish his walk. His speech was confident and assuring. His gait was steady and unfaltering and his whole person seemed the embodiment of health and power.” During the morning he walked at an even pace, cracked jokes and hummed tunes. When the band arrived in the early afternoon, he pushed hard in spurts and clocked 11-minute miles. It was reported that he had no blisters, chaffing, or swelling of his legs.

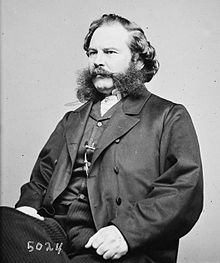

Booths Theatre

Henry Clay Jarrett (1828-1903), the manager of Booth’s Theatre (1869-1965), had bet $2,000 on Weston reaching 500 miles. Jarrett sent messages of encouragement to Weston, and received a reply back, “Success assured. I am the hero of the hour. Have me a box for Monday night.” He received other telegrams from prominent lawyer and politician, Rufus F. Andrews, and W. H. Marston, a famous sailing captain, who both encouraged him.

Mayor Perry

During the last evening, the rink filled up with an enthusiastic crowd of about 6,000 people. Many prominent people attended including “almost the entire medical faculty of Newark.” Mayor Nehemiah Perry (1815-1881) of Newark walked with him a few laps but quit when he could not keep up, causing roars of laughter to come from the crowd.

During the final hour Weston was joined by the chief of police, Peter F. Rogers (1836-1915) and other offices who trotted around him, providing protection. Fifty men were required to keep the narrow track clear. “There was not an inch of room either in the galleries or on the main floor, and the announcements from the judge’s stand were awaited with breathless suspense. As each mile was called from the timekeeper’s desk, the general enthusiasm bubbled over into cheers and at times the noise of the band was lost for whole minutes amid the uproar.”

The Finish – 500 miles in Six Days

After walking 58 miles without a rest, finally the last lap for 500 miles arrived at 11:40 p.m. “As the six days’ trial was narrowed to the last strides, and the final step that measured off the greatest feat of physical endurance on record, he fell into the arms of friends who bore the hero in triumph to the stand.” He had walked his last mile in 11:57.

Weston finally successfully reached 500 miles in six days. “He did his work in about 24 minutes less than the six days, averaging a mile every fourteen minutes and fourteen seconds. The feat has never been accomplished before in this country.”

Weston finally successfully reached 500 miles in six days. “He did his work in about 24 minutes less than the six days, averaging a mile every fourteen minutes and fourteen seconds. The feat has never been accomplished before in this country.”

“Then the great throng broke down every barrier and came like an avalanche toward the stand, amidst the cheers and the tossing of hats and waving of handkerchiefs, Weston with his hollow cheeks, ruffled hair and unmistakable limp, had achieved the unthinkable. Many had tried before him and indeed, he had tried so hard himself, but that day he had accomplished it.” Speeches were given by Mayor Perry and others, but it was hard to hear because of the constant cheering. It was impossible to quiet or disperse the crowd until Weston was taken out.

“Then the great throng broke down every barrier and came like an avalanche toward the stand, amidst the cheers and the tossing of hats and waving of handkerchiefs, Weston with his hollow cheeks, ruffled hair and unmistakable limp, had achieved the unthinkable. Many had tried before him and indeed, he had tried so hard himself, but that day he had accomplished it.” Speeches were given by Mayor Perry and others, but it was hard to hear because of the constant cheering. It was impossible to quiet or disperse the crowd until Weston was taken out.

Weston was thrilled to finally reach his long-sought goal. He credited the kind attention he received from the citizens of Newark and also for the condition of the track he walked on which was much better than the Hippodrome track in New York City.

Weston was thrilled to finally reach his long-sought goal. He credited the kind attention he received from the citizens of Newark and also for the condition of the track he walked on which was much better than the Hippodrome track in New York City.

He was wrapped up in blankets and carried by a coach to the “Mansion House,” looked over by a doctor, and then slept for six hours. In the morning he ate breakfast and then took a stroll and from the rink. After attending church, where they let him pick the hymn, he was featured at a reception in the home of Thomas T. Kinney (1821-1900), editor of the Newark Daily Advertiser, one of the most prominent residents of the city. There he mingled with the richest in the city and had dinner. The citizens of Newark presented him with a gold watch and $1,000.

He was wrapped up in blankets and carried by a coach to the “Mansion House,” looked over by a doctor, and then slept for six hours. In the morning he ate breakfast and then took a stroll and from the rink. After attending church, where they let him pick the hymn, he was featured at a reception in the home of Thomas T. Kinney (1821-1900), editor of the Newark Daily Advertiser, one of the most prominent residents of the city. There he mingled with the richest in the city and had dinner. The citizens of Newark presented him with a gold watch and $1,000.

“The refreshing sleep of Sunday seems to have completely restored him and the peculiar drowsiness that possessed him during the last moments of his walk has, fortunately for him, passed away without injury to his system.”

Positive Reaction

Some of the news press gave Weston credit. “Weston has been sneered at, laughed at, given all manner of names, but he has kept on trying until at last he has fairly walked into the fullest measure of success. It is the long pull that wins, not the long pull at the whisky bottle.” In Brooklyn, “Weston has won his walk. We feared he would. He deserves all the credit which may justly belong to any man who makes repeated and patient efforts to accomplish some almost impossible feat and finally succeeds.” In Boston, “For once Weston can hardly be called a bore.” Doctors said that 500 miles in six days was “the utmost limit of man’s endurance.”

Some of the news press gave Weston credit. “Weston has been sneered at, laughed at, given all manner of names, but he has kept on trying until at last he has fairly walked into the fullest measure of success. It is the long pull that wins, not the long pull at the whisky bottle.” In Brooklyn, “Weston has won his walk. We feared he would. He deserves all the credit which may justly belong to any man who makes repeated and patient efforts to accomplish some almost impossible feat and finally succeeds.” In Boston, “For once Weston can hardly be called a bore.” Doctors said that 500 miles in six days was “the utmost limit of man’s endurance.”

In Michigan it was written, “We take it all back. We have been among them who have experienced some relief in denouncing Weston as a humbug and a habitual boaster who never accomplished what he professed his ability to do. But now that he finally succeeded, it is worthy of editorial mention. He is certainly persevering and plucky, and to accomplish the feat after so many discouraging failures is even a more creditable performance than the success of his first attempt would have been.”

In Illinois, they were convinced that his walk was legitimate after being a laughing stock from his past failures. “If there was ever a greater walk in the age of the world, we have no record of it. Weston has proved himself a first-class pedestrian, and it is to be hoped that he will try and keep his laurels green by not wearying the public with attempts at impossibilities.”

In Missouri: “Weston has been sneered at, laughed at, given all manner of names, but he has kept on trying. We congratulate the plucky pedestrian on the fair accomplishment of his task. No horse in the world could endure such an effort, and we doubt if there is another man in the world possessed of such excellent staying qualities.”

The Brooklyn Union speculated prophetically, “It may open a new and popular field for sporting men, a sort of high-toned amusement in which men of piety and men of the world may mingle in friendly strife.” That seemed like an accurate description of ultrarunning in the years to come. But the Boston Post just could not comprehend the benefits of such a sport where a man walks round and round “like a patient horse attached to a rural cider-press.”

The Brooklyn Union speculated prophetically, “It may open a new and popular field for sporting men, a sort of high-toned amusement in which men of piety and men of the world may mingle in friendly strife.” That seemed like an accurate description of ultrarunning in the years to come. But the Boston Post just could not comprehend the benefits of such a sport where a man walks round and round “like a patient horse attached to a rural cider-press.”

Negative Reaction

But the Newark Courier was highly critical of Weston in an article entitled, “Humbug Weston.” It read, “It is astonishing that this man Weston should be tolerated in any community.” The main criticism was that Weston would not submit himself to a true judged walking match against others. When would he participate in a race? “There are fifty gentlemen amateurs in this city who could walk the heart clean out of him at long or short distances.” Meanwhile, in Chicago a newcomer, Daniel O’ Leary had recently walked 200 miles in 36:29, invading Weston’s Pedestrian space and that city called O’Leary, not Weston, “the champion pedestrian of the world.”

The Courier said that instead of racing, Weston paraded around carrying a hat for innocent people to put pennies in. “Weston should procure a hand-organ and a monkey, and thus in a musical manner he could at least earn the pennies.” The article doubted his 500 miles were legit and concluded in a particular cruel way for that era. “Cannot someone in authority have him engaged as a mail carrier in the Indian country and pick him out a good scalping territory?”

Another newspaper in New Jersey was critical about betting on such endurance events. “Fools and their money are soon parted. Suppose next time he tries to eat a bushel of turnips in one sitting. Suppose he swallows a mackerel whole, bones and all, without winking?”

Two newspapers in New York City printed charges that the accomplishment was a fraud, that the main judge was one of Weston’s men. But these charges of cheating were solely based on information from an anonymous man who believed Weston was “the grossest humbug that ever practiced in the city.” Weston threatened the newspaper with libel, but never followed through. Newark city officials came to his defense, “There is not a particle of doubt as to the correctness of the record of this performance.” A certificate was created with the signatures of the judges. Weston actually walked further that 500 miles. He walked some laps while two of the judges were away and he insisted that those laps not be counted so there would not be any “loop-hole” for a charge of unfairness.

Two newspapers in New York City printed charges that the accomplishment was a fraud, that the main judge was one of Weston’s men. But these charges of cheating were solely based on information from an anonymous man who believed Weston was “the grossest humbug that ever practiced in the city.” Weston threatened the newspaper with libel, but never followed through. Newark city officials came to his defense, “There is not a particle of doubt as to the correctness of the record of this performance.” A certificate was created with the signatures of the judges. Weston actually walked further that 500 miles. He walked some laps while two of the judges were away and he insisted that those laps not be counted so there would not be any “loop-hole” for a charge of unfairness.

Despite the criticism, the most credible evidence showed that Weston had accomplished what people of the era thought was impossible and had never been accomplished by legendary Foster Powell who at started it all. The 500-mile barrier had been broken, ready for others to also achieve it.

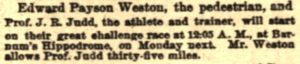

The First Formal Six-Day Race

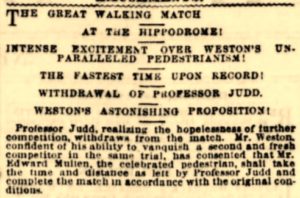

Professor Judd, seeking fame and fortune, seized on the doubt drummed up by Weston’s critics and issued a challenge on February 4, 1875, for Weston to compete against him in what would be the first six-day race in history. Judd wrote to, “Considerable doubt appears to be entertained as to your recent performance at the rink in Newark, and many would like to convince themselves of the ability of a human being to perform such a task.” Weston at first declined, mentioning that he had promised to next walk next against an Englishman. Judd countered, that he was indeed born in England.

Perhaps P.T. Barnum was behind the challenge, because just eight days later, it was announced that Weston accepted Judd’s challenge, and arrangements had already been made for the race to be conducted in the Hippodrome. The winner would receive 5,000,(5,000, (5,000,(126,000 in today’s value) with a possible bonus of $2,500 if they walked 115 miles during the first day and if they walked 500 miles or more in six days. The event was billed as “The greatest competitive trial of endurance ever attempted.” Judges were chosen by each side from various athletic clubs in New York City and New Jersey.

Perhaps P.T. Barnum was behind the challenge, because just eight days later, it was announced that Weston accepted Judd’s challenge, and arrangements had already been made for the race to be conducted in the Hippodrome. The winner would receive 5,000,(5,000, (5,000,(126,000 in today’s value) with a possible bonus of $2,500 if they walked 115 miles during the first day and if they walked 500 miles or more in six days. The event was billed as “The greatest competitive trial of endurance ever attempted.” Judges were chosen by each side from various athletic clubs in New York City and New Jersey.

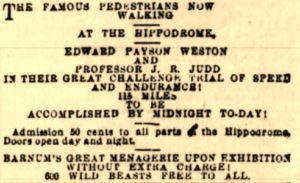

Barnum announced that the Hippodrome was soon going to be closed for good in New York because of waning interest and huge expenses. In mid-April, his mobile Hippodrome would go on the road, traveling to large cities across America. This six-day race would be the major concluding event for the New York Hippodrome. It was speculated, “Barnum will, with his usual luck, make a small fortune in the speculation.”

Barnum announced that the Hippodrome was soon going to be closed for good in New York because of waning interest and huge expenses. In mid-April, his mobile Hippodrome would go on the road, traveling to large cities across America. This six-day race would be the major concluding event for the New York Hippodrome. It was speculated, “Barnum will, with his usual luck, make a small fortune in the speculation.”

Because this was the first race of its kind, organizers worried that the two walkers would come in contact with each other during the race. So, it was decided that the men would compete on separate tracks. The difference in their lengths was taken into account. Weston would walk on the inner track.

Because this was the first race of its kind, organizers worried that the two walkers would come in contact with each other during the race. So, it was decided that the men would compete on separate tracks. The difference in their lengths was taken into account. Weston would walk on the inner track.

Weston would credit Judd 35 miles. No, Judd would not be given a 35-mile head start, he would be credited with 35 miles that he would not walk, requiring Weston to walk 35 miles further by the end of six days in order to win. The walking style needed to be “fair heel-and-toe walk.” Heavy betting occurred, about 4 to 1 in favor of Weston. “Both men had tents pitched in the ring to be used for rubbing down and resting.”

About an hour before the race, 200 fans and the two contestants arrived at the Hippodrome and inspected all the arrangements. “Weston was clad in black velvet, patent leather gaiters and black kids, looked as if dressed for a flower show. Judd was down to business and wore a blue flannel costume suitable to the occasion.” Weston weighed in at 135 pounds, Judd a few pounds less. Weston’s manager was Fred J. Engelhardt, a prominent sports promoter and trainer, originally from Germany. Judd was handled by “celebrated ten-mile runner” John “Jack” B. Grindall.

About an hour before the race, 200 fans and the two contestants arrived at the Hippodrome and inspected all the arrangements. “Weston was clad in black velvet, patent leather gaiters and black kids, looked as if dressed for a flower show. Judd was down to business and wore a blue flannel costume suitable to the occasion.” Weston weighed in at 135 pounds, Judd a few pounds less. Weston’s manager was Fred J. Engelhardt, a prominent sports promoter and trainer, originally from Germany. Judd was handled by “celebrated ten-mile runner” John “Jack” B. Grindall.

The Start

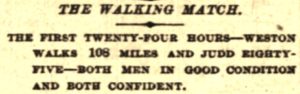

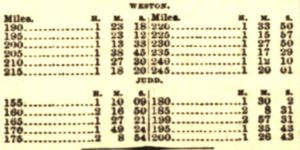

The historic first six-day race began on March 1, 1875, at 12:13 a.m. “Judd started off with a dogged air and plodded heavily with his accustomed working of the shoulders. Weston carried himself jauntily and easily and looked altogether the best walker.” They were sent off by about 100 spectators who shouted, “Bully for Weston” and “Bully for Judd.” Judd took the lead during the first mile, but Weston overtook him on mile two and never gave it up. He reached 25 miles in 5:21 and after reaching 50 miles, averaged every mile in about 13 minutes. Weston reached 100 miles in about 21:39:00 and then went on and finished that first day with 107 miles with Judd, obviously a pretender, was far behind at 85 miles. “Weston was walking with great pluck, and though apparently a little stiff was full of grit and confidence.”

The historic first six-day race began on March 1, 1875, at 12:13 a.m. “Judd started off with a dogged air and plodded heavily with his accustomed working of the shoulders. Weston carried himself jauntily and easily and looked altogether the best walker.” They were sent off by about 100 spectators who shouted, “Bully for Weston” and “Bully for Judd.” Judd took the lead during the first mile, but Weston overtook him on mile two and never gave it up. He reached 25 miles in 5:21 and after reaching 50 miles, averaged every mile in about 13 minutes. Weston reached 100 miles in about 21:39:00 and then went on and finished that first day with 107 miles with Judd, obviously a pretender, was far behind at 85 miles. “Weston was walking with great pluck, and though apparently a little stiff was full of grit and confidence.”

Day Two

Both men were back on the track at 4 a.m. on day two but were not moving well. The crowd on-hand was “exceedingly small” but had a keen interest watching the two men tramping along the track. Weston was able to pick up the pace later in the day and Judd was struggling. “He looked and walked as though a little weary and seemed to do almost as much work with his shoulders as with his legs and feet.” He slowed to a 20-minute-mile pace and started to look lame. Weston kept lapping him and there seemed to be little doubt that he would beat Judd badly by the end of the week. By the end of day two, Weston finished with 179 total miles to Judd’s 149, almost making up the 35-mile advantage given.

Both men were back on the track at 4 a.m. on day two but were not moving well. The crowd on-hand was “exceedingly small” but had a keen interest watching the two men tramping along the track. Weston was able to pick up the pace later in the day and Judd was struggling. “He looked and walked as though a little weary and seemed to do almost as much work with his shoulders as with his legs and feet.” He slowed to a 20-minute-mile pace and started to look lame. Weston kept lapping him and there seemed to be little doubt that he would beat Judd badly by the end of the week. By the end of day two, Weston finished with 179 total miles to Judd’s 149, almost making up the 35-mile advantage given.

The press knew that Judd was in trouble. “His system of training will need to come out strong pretty soon or it will be too late to win the race. The old proverb about the tortoise isn’t worth a pinch of snuff opposed to a hare like Weston, with somebody to wake him every hour.”

Day Three

Judd needed to catch up and went back on the track on day three, two hours before Weston. Finally, a larger crowd came to watch, despite a severe snowstorm. Judd still struggled, walked even slower than the day before. He was described as looking like a man who had just risen from a sick bed. “He was low-spirited and walked doggedly along, with a lowering brow and discontented look, and showing by every action that it was only by a great effort that he kept on the track at all.” His handlers said Judd had an ugly temper and that it was impossible to please him. He achieved 51 miles during the day, reaching 200. Weston on the other hand “walked like a man full of courage and grit, with a countenance overspread with smiles.” He reached 245, adding nine more miles before retiring to bed for 254.

Judd needed to catch up and went back on the track on day three, two hours before Weston. Finally, a larger crowd came to watch, despite a severe snowstorm. Judd still struggled, walked even slower than the day before. He was described as looking like a man who had just risen from a sick bed. “He was low-spirited and walked doggedly along, with a lowering brow and discontented look, and showing by every action that it was only by a great effort that he kept on the track at all.” His handlers said Judd had an ugly temper and that it was impossible to please him. He achieved 51 miles during the day, reaching 200. Weston on the other hand “walked like a man full of courage and grit, with a countenance overspread with smiles.” He reached 245, adding nine more miles before retiring to bed for 254.

Day Four

On day four, the spectators packed the Hippodrome, hoping to watch some good competition. Judd’s handlers hoped that he would recover with a long night’s sleep. “When Judd appeared on the track in the morning there was no mistaking the signs which showed that he could at the most only crawl around the course. He managed to get around the track five times and then needed to rest.” He had terribly sore feet and gave up after logging a total of 217 miles by the afternoon.

On day four, the spectators packed the Hippodrome, hoping to watch some good competition. Judd’s handlers hoped that he would recover with a long night’s sleep. “When Judd appeared on the track in the morning there was no mistaking the signs which showed that he could at the most only crawl around the course. He managed to get around the track five times and then needed to rest.” He had terribly sore feet and gave up after logging a total of 217 miles by the afternoon.

Weston was the winner of the $5,000, but the show needed to go on to attract spectator interest and Weston needed to go the full six days according to the terms of the agreement with Barnum. Edward Mullen of Boston (yes, the infamous Mullen from episode 94) came out at 3:45 p.m. to substitute for Judd. He was credited Judd’s 217 miles, plus the 35-mile advantage, for a starting distance of 252 miles. Weston, with an eighteen-mile lead over that figure, was initially in agreement with this arrangement. Because Mullen was fresh, the crowd enjoyed watching him fly around the track, but soon his pace slowed down significantly.

Weston was the winner of the $5,000, but the show needed to go on to attract spectator interest and Weston needed to go the full six days according to the terms of the agreement with Barnum. Edward Mullen of Boston (yes, the infamous Mullen from episode 94) came out at 3:45 p.m. to substitute for Judd. He was credited Judd’s 217 miles, plus the 35-mile advantage, for a starting distance of 252 miles. Weston, with an eighteen-mile lead over that figure, was initially in agreement with this arrangement. Because Mullen was fresh, the crowd enjoyed watching him fly around the track, but soon his pace slowed down significantly.

By the time the gas lights were lit for the evening, Weston was walking stiff with a very sore right foot. He reached about 313 miles by the end of the day, still ahead of the Judd+Mullen+35 tally of 293 miles. Weston had actually widened the lead by two miles since Mullen had taken over for Judd. During the evening, Judd came back out as Weston and Mullen were both walking and added five more miles to his personal tally to reach 222 miles. It was said, “His walk was like that of a man of 80.”

By the time the gas lights were lit for the evening, Weston was walking stiff with a very sore right foot. He reached about 313 miles by the end of the day, still ahead of the Judd+Mullen+35 tally of 293 miles. Weston had actually widened the lead by two miles since Mullen had taken over for Judd. During the evening, Judd came back out as Weston and Mullen were both walking and added five more miles to his personal tally to reach 222 miles. It was said, “His walk was like that of a man of 80.”

Day Five

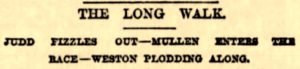

On day five, Mullen suffered from a blistered foot and broke down quickly. He eventually quit at 4:30 p.m. reaching personally, 89 miles, bringing the challenger relay-tally to 341 miles. He blamed his failure on a lack of training and not taking care of his feet while competing. After Mullen left, Weston stopped to give a speech to the audience, boasting about his great performances as a pedestrian, and how this race came about.

A few hours later, George B Coyle (1844-1880), an unknown pedestrian who claimed to be the champion of Wisconsin, was brought out as a second replacement for Judd. He started his walk at 8:30 p.m. with a strong pace. At that point Weston retired to bed with about 364 miles, and a 23-mile lead. After a short rest, he came back out expressed confidence that he would out-walk the new competitor. He showed greater energy than at any time that day, finishing with about 370 miles. Coyle, not sleep deprived, kept up his walk late into the night after Weston retired.

Day Six

Coyle walked strongly on day six, ever closing the gap on Weston. Both first looked very exhausted but walked better as the day went on. Weston reached 400 miles at noon. During that mile, he asked the band to play his favorite song, “Tommy Dodd.” Coyle reached 55 miles, bringing the challenger relay-total (including the 35 bonus miles) to 396, just four miles behind. “During the remainder of the day the walking was comparatively slow, both contestants stopping frequently for refreshments.”

Coyle walked strongly on day six, ever closing the gap on Weston. Both first looked very exhausted but walked better as the day went on. Weston reached 400 miles at noon. During that mile, he asked the band to play his favorite song, “Tommy Dodd.” Coyle reached 55 miles, bringing the challenger relay-total (including the 35 bonus miles) to 396, just four miles behind. “During the remainder of the day the walking was comparatively slow, both contestants stopping frequently for refreshments.”

Toward the end of the event, a controversy arose. Mullen boldly came out on the track again to get attention, trying to make up for his embarrassing defeat. He started giving a fast-walking exhibition for the audience with permission from the Hippodrome managers. Weston threw a fit, not wanting Mullen to take the spotlight off him. He demanded that Mullen be removed from the track and warned that if not, he would stop. Weston made his threat good and stopped walking until the police removed Mullen. This caused “considerable dissatisfaction among the rowdy element in the audience.”

The Finish

At the end, Weston reached 431 miles. Coyle reached 95 miles during his turn, bringing the challenger relay total to 436 miles (including the 35-mile handicap). Weston claimed he could have easily reached 500 miles but took it easy once Judd had quit. His friend, New Jersey politician, Rufus F. Andrews, said that Weston never intended to reach 500 miles unless pushed by his competitor because he had an injured hip.

The final tally of the first six day race was:

- Weston – 431 miles

- Judd – 222 miles

- Coyle – 95 miles

- Mullen – 91 miles

Critics of Weston Silenced

Critics of Weston were mostly silent. During the first six-day race, not only did he beat his main competition, but he out-distanced two others who joined in on fresh legs. A favorable voice in New York City said, “The result of the six days’ walk has now converted the unbelievers into believers of the most enthusiastic order.” Members of the New York and New Jersey athletic clubs signed a certificate showing that Weston was the leading pedestrian in the United States.

Critics of Weston were mostly silent. During the first six-day race, not only did he beat his main competition, but he out-distanced two others who joined in on fresh legs. A favorable voice in New York City said, “The result of the six days’ walk has now converted the unbelievers into believers of the most enthusiastic order.” Members of the New York and New Jersey athletic clubs signed a certificate showing that Weston was the leading pedestrian in the United States.

One observer broke down this first six-day race and gave huge credit to Weston’s crew. “Weston was splendidly handled and availed himself of every advantage that could be received from good medical and bodily attendance. His regulations were stringent, and everything was ready for him on the slightest notice. Judd, on the contrary, depended too much on himself and his own powers of endurance.” Also Weston had built up strength with all of his extreme walks during the past year and developed the ability to regain strength with only two to three hours of sleep.

Barnum was thrilled with the race. “Mr. Barnum, appreciating the unparalleled success attained by this famous pedestrian in defeating three separate and fresh antagonists in the late match, and desiring to give a substantial recognition of the wonderful endurance displayed by Mr. Weston, has gendered the gratuitous use of the Hippodrome for a testimonial benefit, the proceeds of which are to be given to Mr. Weston’s children.” Less than two days after finishing, Weston attempted to walk 50 miles in 11 hours without food or rest. He came close and reached 46 miles.

Barnum was thrilled with the race. “Mr. Barnum, appreciating the unparalleled success attained by this famous pedestrian in defeating three separate and fresh antagonists in the late match, and desiring to give a substantial recognition of the wonderful endurance displayed by Mr. Weston, has gendered the gratuitous use of the Hippodrome for a testimonial benefit, the proceeds of which are to be given to Mr. Weston’s children.” Less than two days after finishing, Weston attempted to walk 50 miles in 11 hours without food or rest. He came close and reached 46 miles.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources

- Andy Milroy, The History of the 6 Day Race

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- P. S. Marshall, Weston, Weston, Rah-Rah-Rah!

- Toms Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultramarathoning: The Next Challenge

- William L. Slout, Rags to Ricketts and Other Essays on Circus History

- T. Barnum, Barnum’s Own Story: The Autobiography of P.T. Barnum

- Fayette County Herald (Washington, Ohio), Aug 24, 1871

- Matawan Journal (New Jersey), Dec 5, 19, 1874

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Dec 24, 1874

- New York Times (New York), Dec 19-21, 1874, Feb 25-27, Mar 2-7, 1875

- The Times Herald (Port Huron, Michigan), Dec 24, 1874

- The Memphis Reveille (Missouri), Jan 7, 1875

- The Rutland Daily Globe (Vermont), Dec 9, 1874

- The Philadelphia Inquirer (Pennsylvania), Dec 11, 1874

- The Cairo Bulletin (Illinois), Dec 13, 1874

- Buffalo Morning Express (New York), Oct 15, Dec 25, 1874

- The Brooklyn Union (New York), Dec 12, 21, Mar 3, Apr 12, 1874

- Boston Post (Massachusetts), Nov 7, Dec 14, 22, 1874

- Boston Evening Transcript (Massachusetts), Dec 14, 1874

- Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Dec 21, 1874

- Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), Dec 24, 1874

- Carbondale Advance (Pennsylvania), Dec 26, 1874

- The Luzerne Union (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania), Dec 30, 1874

- Shelby County Herald (Missouri), Jan 6, 1875

- The Waukegan Weekly Gazette (Illinois), Jan 16, 1875

- The Buffalo Sunday Morning News (New York), Jan 3, 1875

- The Memphis Reveille (Missouri), Jan 7, 1875

- Columbus Era (Nebraska), Feb 20, 1875

- Harrisburg Telegraph (Pennsylvania), Feb 13, 1875

- New York Daily Herald (New York), Mar 1-7, 1875

- The San Francisco Examiner (California), Mar 5, 1875

- The Sun (New York, New York), Mar 5, 1875

- New York Tribune (New York), Mar 5, 1875

- The New Orleans Bulletin (Louisianna), Mar 12, 1875

- Hamilton Daily Times (England), Mar 2, 1875