Daniel O'Leary and Edward Payson Weston race for six days (original) (raw)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 24:51 — 28.5MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

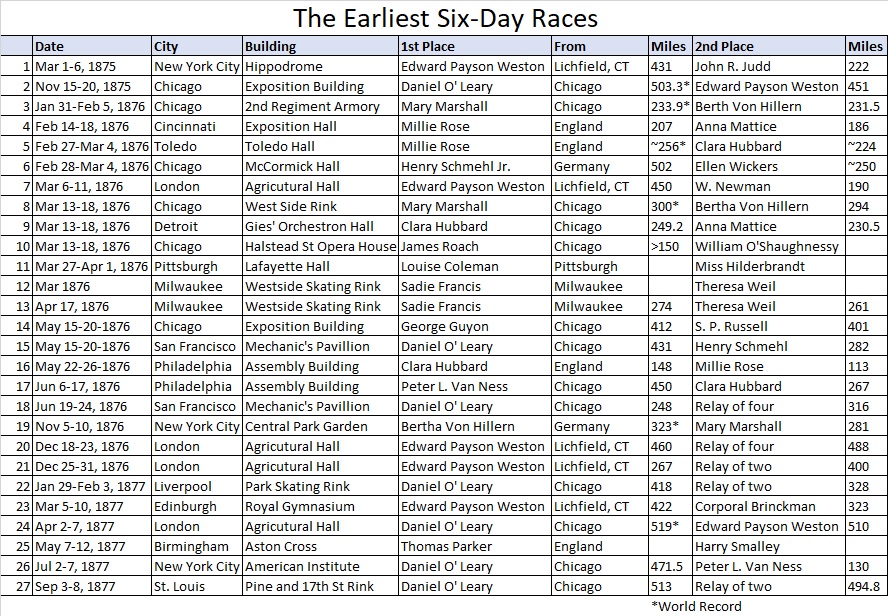

In America, 1876 had been a “loopy” six-day race year, with at least eighteen races held. Interest was high, but there were also skeptics. Closing out the last episode, Daniel O’Leary, of Chicago, the champion pedestrian of the world, reached 500 miles for the third time in six days, but his reputation had been tarnished due to some false accusations that in some people’s minds also put a black eye on the ultra-distance sport.

In America, 1876 had been a “loopy” six-day race year, with at least eighteen races held. Interest was high, but there were also skeptics. Closing out the last episode, Daniel O’Leary, of Chicago, the champion pedestrian of the world, reached 500 miles for the third time in six days, but his reputation had been tarnished due to some false accusations that in some people’s minds also put a black eye on the ultra-distance sport.

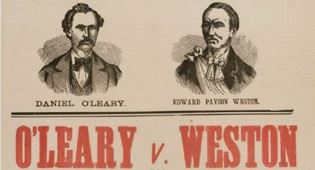

With criticism swirling around him, it was time for O’Leary to show England that he was the true champion ultrarunning/pedestrian of the world, not Edward Payson Weston, who had been winning over the British respect and their money for months. By going to England, O’Leary would face off in a rematch with Weston for their historic second six-day race. It would receive nearly as much attention as the Ali vs. Frazer II boxing match that took place 97 years later in Madison Square Garden. O’Leary would become a key figure in the history of the sport that attracted international excitement for the six-day race, and also would bring back a massive fortune.

O’Leary Heads to England

In late September 1876, while O’Leary was on a ship crossing the Atlantic, Weston finally succeeded reaching 500 miles in six days for the second time. This was accomplished at the Ice-Skating Rink at Toxteth Park, in Liverpool and he went a little further, to 500.5 miles.

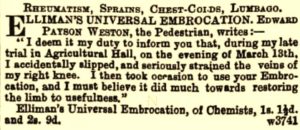

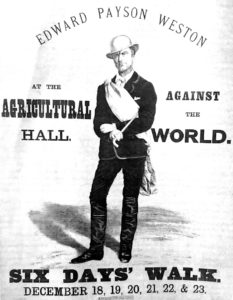

Weston Ad

O’Leary arrived in London a few days later, in early October, and immediately tried to help the British understand that he was the true pedestrian champion, not Weston. O’Leary wrote, “I am desirous of forever settling the question, ‘Who shall be the champion pedestrian of the world? Should Weston be desirous of entering into a side-by-side contest of 500 miles with me, I hereby agree to give him a start of 25 miles in that distance.” Weston ignored O’Leary’s challenge and didn’t want to share the spotlight that was shining on him by the British public. He was even getting money from a product endorsement, doing ads for a cream to help with rheumatism, sprains, chest-colds, and lumbago.

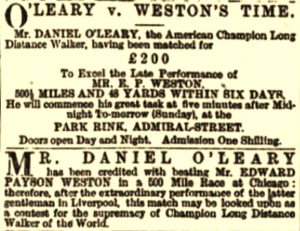

O’Leary Beats Weston’s Six-day Mark in Liverpool

Frustrated that a race could not be scheduled, O’Leary wanted to prove to the British that he was better than Weston. He also went to Liverpool, determined to beat Weston’s recent mark set there of 500.5 miles in six days. On October 16-21, he also walked in the Admiral Street Skating Rink at Toxteth Park on a track measured 11 laps to a mile. Sam Hauge (1828-1901) of Liverpool, organized the event with a bet against O’Leary of £100, that O’Leary could not beat Weston’s recent solo six-day mark of 500.5 miles under the exact same conditions on the same track. The English, skeptical of this newcomer, commented, “He is much prettier and a more rapid walker than Weston, but his dress is not near so neat as that worn by Weston.” To the British, how you looked was just as important as how you performed.

Frustrated that a race could not be scheduled, O’Leary wanted to prove to the British that he was better than Weston. He also went to Liverpool, determined to beat Weston’s recent mark set there of 500.5 miles in six days. On October 16-21, he also walked in the Admiral Street Skating Rink at Toxteth Park on a track measured 11 laps to a mile. Sam Hauge (1828-1901) of Liverpool, organized the event with a bet against O’Leary of £100, that O’Leary could not beat Weston’s recent solo six-day mark of 500.5 miles under the exact same conditions on the same track. The English, skeptical of this newcomer, commented, “He is much prettier and a more rapid walker than Weston, but his dress is not near so neat as that worn by Weston.” To the British, how you looked was just as important as how you performed.

Interest in Liverpool was intense. Trams were filled, taking spectators to the rink where they would pay one shilling to watch day and night, and be entertained by a band. O’Leary walked strongly on the first day, reaching 106 miles. On day two, show fatigue, he reached 169 miles and was 11 miles behind Weston’s pace. He usually walked with a pacer who helped keep him awake by chatting and he improved, reaching 263 miles after three days despite being ill. Unable to take in solid food, he fueled mostly on soup and “slops.” He didn’t like walking to the music of a brass band, so a string orchestra replaced it. On the final days he lived on oysters stewed in milk. After five days, he reached 427 miles, and it was believed to be “doubtless” that he would succeed.

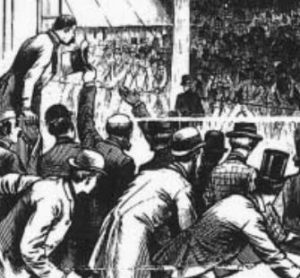

On the last day, the building was so packed that hundreds had to be turned away. “The crowd swayed to and fro like a mighty wave, and the noise, excitement, and confusion which prevailed were indescribable. The enclosure was crowded to such a degree that it was almost a matter of impossibility for one to budge from the spot where he located himself.” O’Leary reached 500 miles in a little less than 143 hours, and 502 miles in 143:46:00, his fourth time reaching the 500-mile distance, and just a mile short of his world record 503 miles. After the finish, he was cheered on by a large audience of Irishmen for about five minutes, with repeated cries of “O’Leary, O’Leary, O’Leary.” The promoter, Hague gave a speech and heaped praise on O’Leary. “After which the doors were thrown open, and the people elbowed their way out of the Rink in the best way possible.”

The British press properly recognized the feat. “This is perhaps the most wonderful feat that has ever been chronicled in the history of pedestrianism, and it is doubly remarkable from the fact that it completely eclipses Mr. E. P. Weston’s famous walk on a recent occasion. After this wonderful achievement, O’Leary felt pretty confident that he could again give his former opponent a licking, and this feeling seems also to have been entertained by a large portion of that section of the community which makes pedestrianism its special hobby.” Yes, O’Leary successfully knocked Weston down a peg or two from his pedestal and the sporting community wanted to witness a showdown between the two.

The British press properly recognized the feat. “This is perhaps the most wonderful feat that has ever been chronicled in the history of pedestrianism, and it is doubly remarkable from the fact that it completely eclipses Mr. E. P. Weston’s famous walk on a recent occasion. After this wonderful achievement, O’Leary felt pretty confident that he could again give his former opponent a licking, and this feeling seems also to have been entertained by a large portion of that section of the community which makes pedestrianism its special hobby.” Yes, O’Leary successfully knocked Weston down a peg or two from his pedestal and the sporting community wanted to witness a showdown between the two.

The British now had someone to compare against Weston and words of criticism were printed about him. “Weston’s walking was utterly opposed to all pre-conceived ideas among Englishmen of what pedestrianism should be. His fantastic dress was accepted as a piece of Yankeeism which might be forgiven, but the rollicking style in which he tripped round the path was never favorably regarded. O’Leary’s style is much after the English model and was decidedly in favor with the majority of those who witnessed the performance.”

Weston Against the World for Six Days

Weston felt the pressure from both O’Leary and the British public to respond to a challenge for another six-day race between the two. An agreement was reached to hold the rematch on December 18, 1876, but the race fell through.

Weston felt the pressure from both O’Leary and the British public to respond to a challenge for another six-day race between the two. An agreement was reached to hold the rematch on December 18, 1876, but the race fell through.

Weston was still dodging O’Leary when he participated in a six-day race at the Agricultural Hall in London called, “Edward Payson Weston Against the World.” There clearly were no true British challengers for either Weston or O’Leary in a six-day race, so someone came up with the idea for Weston to race against a relay consisting of some of the best long-distance walkers in England.

George Ide

On December 18-23, 1876, Weston raced against:

- George N. Ide, (1843-1926) age 33, of North Woolwich, who recently set a 50-mile world record at Lillie Bridge, in 8:19:55.

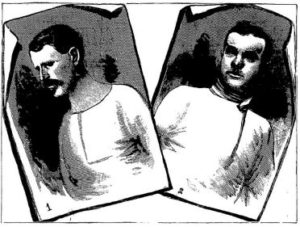

Parry and Crossland

George Parry, (1841-1899), age 35, a mason, of Manchester, who gained fame when he raced head-to-head against Weston for 24 hours in April 1876 at Pomona Gardens, Manchester with only a week of training. He reached 97 miles to Weston’s 111. A few months later Parry reached 114 miles in 24 hours.- Peter Crossland (1842-1899), age 34, a cutler (knife maker), of Sheffield who was known as “The Sharp Sheffield Blade.” He was also the 24-hour world record holder. He achieved 120 miles, 1560 yards on Sept 12, 1876, at Pomona Gardens in Manchester. He had also recently raced against O’Leary for four days, on November 20-23, 1876, at the same venue, reaching 241 miles to O’Leary’s 258.

None of these walkers trained specifically for the event and they would walk two days each. After the race started, nasty yellow fog hovered in the building that bothered the walkers. After the first 48 hours, Weston walked 186 miles to Ide’s 153.5. But as Weston slowed, and a fresh George Parry walked, the relay caught up after another 12 hours and it was neck-and-neck through three days. Parry finished his two-day turn with 163.5 miles. Crossland took over and accomplished 170 miles. The relay won with 487 miles to Weston’s 460 miles.

Weston vs. Two-Man Relay for Six Days

Peter Crossland

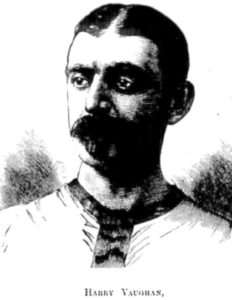

Weston wasn’t finished for the year. With one-week’s rest, on Boxing Day, December 25, 1876, he started another multi-day race for five days in Agricultural Hall against a relay of two Brits, Harry Vaughan (1848-1888), a carpenter/architect from Chester, and current 100-mile world record holder, and Peter Crossland (1839-1899), “The Sharp Sheffield Blade.” Each walked alternate days against Weston. Weston had a goal and wager to reach 400 miles. As expected with little recovery since his last race, he lost, reaching only 267 miles to the relay’s 300 miles. After the finish, Weston rudely refused to come out to address the crowd as he usually did, because he was annoyed with the treatment that he received from everyone.

Weston wasn’t finished for the year. With one-week’s rest, on Boxing Day, December 25, 1876, he started another multi-day race for five days in Agricultural Hall against a relay of two Brits, Harry Vaughan (1848-1888), a carpenter/architect from Chester, and current 100-mile world record holder, and Peter Crossland (1839-1899), “The Sharp Sheffield Blade.” Each walked alternate days against Weston. Weston had a goal and wager to reach 400 miles. As expected with little recovery since his last race, he lost, reaching only 267 miles to the relay’s 300 miles. After the finish, Weston rudely refused to come out to address the crowd as he usually did, because he was annoyed with the treatment that he received from everyone.

London

During that same week, O’Leary walked against William Howes, (1839-) age 37, of Norwich, in a 300-mile (72-hours) race at Victoria Skating Rink in Cambridge Heath, near London. O’Leary gave up after 203 miles because he had been suffering from terrible diarrhea. Howes was declared the winner. It was O’Leary’s first public defeat. The venue had some terrible canvas roofing letting in the rain, causing the track to be a flooded, muddy mess at times. Howes later accused O’Leary of faking his illness to avoid admitting to a legitimate defeat. He also blasted Weston, who wound not dare race him because he only cared for “circus performances.”

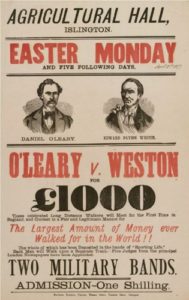

Plans for The Great Walking Contest of 1877

While Weston’s first relay race was taking place, it was revealed on December 19, 1876, that a “Great Walking Contest” was in the works for 1877 at the Agricultural Hall in London. An anonymous English person who signed his name, “Anti-Humbug” (certainly referring to Weston as being a humbug), deposited £500, issuing a challenge for a six-day race in the new future. Sir John Astley who had been on hand to witness Weston’s first six-day race in England (see episode 99), immediately also deposited £500, backing Weston to meet that challenge. For Weston, £1000 was too much to ignore.

While Weston’s first relay race was taking place, it was revealed on December 19, 1876, that a “Great Walking Contest” was in the works for 1877 at the Agricultural Hall in London. An anonymous English person who signed his name, “Anti-Humbug” (certainly referring to Weston as being a humbug), deposited £500, issuing a challenge for a six-day race in the new future. Sir John Astley who had been on hand to witness Weston’s first six-day race in England (see episode 99), immediately also deposited £500, backing Weston to meet that challenge. For Weston, £1000 was too much to ignore.

Agricultural Hall

O’Leary quickly sent a check for £100 to secure his spot in the race. It looked like Weston would have to race against O’Leary again. Others were invited too. Along with £1000 going to the winner, he would also get 2/3rd of the gate money, after expenses were deducted, potentially a huge fortune. It was speculated, “A gigantic match of this description is unequaled in the annals of pedestrianism.” Astley immediately offered a 100-pound bet that Weston would walk over 505 miles and that no man would beat him. The Sportsman newspaper held the money as the stakeholder and claimed the privilege of naming judges for the race.

William Howes

It soon was revealed the William Howes was the “unknown challenger” the “Anti-Humbug.” The race date was fixed for April 2-7, 1877, but Howes announced that he couldn’t race for three months, because of an injured toe, and demanded a postponement. But the show needed to go on and in early January 1877, both Weston and O’Leary signed articles of agreement for the match. They were willing to walk outdoors at Lillie Bridge, the headquarters of the London Athletic Club, if the Agricultural Hall in Islington, London, could not be scheduled. “This is the most important match of its kind ever set for decision in this country. On paper the relative merits of both men appear very evenly balanced in six days walking and the struggle will in all probably be a very close one.” People back in Chicago heard about the planned race and were wagering that the race would never take place, that Weston would back out.

Both competitors trained by continuing to compete in six-day races. O’Leary raced against two rookie walkers in a relay at Liverpool. He reached 418 miles to 328 for the relay. He then experienced a loss in a 72-hour race against Peter Crossland who reached 287 miles, setting a 72-hour world best, to O’Leary’s 268 miles.

Weston competed in a six-day race against a walking rookie, Corporal Brinckman in Edinburgh, Scotland. Weston reached 422 miles to Brinckman’s 323 miles. Weston blamed his failure to reach 500 miles on an accident that injured him. The crowd was small on the last day because Weston doubled the admission price. He felt bitter and said that he was sorry that the public had failed to appreciate his performance and lost about £100s on the event.

Weston competed in a six-day race against a walking rookie, Corporal Brinckman in Edinburgh, Scotland. Weston reached 422 miles to Brinckman’s 323 miles. Weston blamed his failure to reach 500 miles on an accident that injured him. The crowd was small on the last day because Weston doubled the admission price. He felt bitter and said that he was sorry that the public had failed to appreciate his performance and lost about £100s on the event.

The Great Walking Match – Weston vs Oleary II

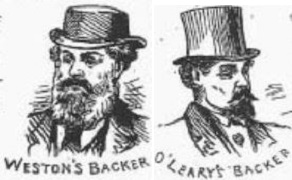

In early March 1877, to everyone’s excitement, Sporting Life announced that the Weston-O’Leary rematch agreements were finalized that the money needed had been deposited by both Weston’s backer (Sir John Astley) and O’Leary’s backer (Sam Hague). “The match is a genuine one in every respect, and each man is sure to have a fair field and no favor, which is all either they or their supporters require.” It would be held in the Agricultural Hall.

In early March 1877, to everyone’s excitement, Sporting Life announced that the Weston-O’Leary rematch agreements were finalized that the money needed had been deposited by both Weston’s backer (Sir John Astley) and O’Leary’s backer (Sam Hague). “The match is a genuine one in every respect, and each man is sure to have a fair field and no favor, which is all either they or their supporters require.” It would be held in the Agricultural Hall.

Sir John Astley

Sir John Dugdale Astley (1828-1894), Weston’s backer, was a member of Parliament representing North Lincolnshire. He grew up in a wealthy family and was a lieutenant colonel in the Scots Fusilier Guards, serving in the 1854 Crimea War where he was wounded in the neck at the Battle of Alma. He was a great sportsman and himself a runner at the sprint distance. Like P.T. Barnum in America who was the first major promoter of ultrarunning, Astley would become the first prominent ultrarunning promoter in England.

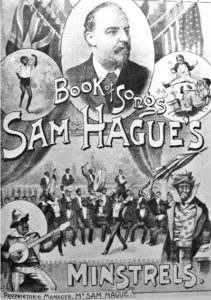

Sam Hague (1828-1901), O’Leary’s backer, was a famous entertainer of the time who gave traveling performances of his Minstrels, much like a circus with acrobats, dancers, and musicians, made up in blackface. Like P.T. Barnum, he had a particular interest in Pedestrianism, and he and been the person who had put up the original £500 for the upcoming Weston-O’Leary April rematch. Just a couple of months earlier he was betting against O’Leary, but this time he was O’Leary’s backer.

Sam Hague (1828-1901), O’Leary’s backer, was a famous entertainer of the time who gave traveling performances of his Minstrels, much like a circus with acrobats, dancers, and musicians, made up in blackface. Like P.T. Barnum, he had a particular interest in Pedestrianism, and he and been the person who had put up the original £500 for the upcoming Weston-O’Leary April rematch. Just a couple of months earlier he was betting against O’Leary, but this time he was O’Leary’s backer.

There was a lot of work to be performed behind the scenes to pull over the event. For example, a labor conflict arose when the judges demanded to be paid time-and-a-half for their long hours. Two bands were hired to play from 5 a.m. to midnight and the two walkers would oversee which tunes were played in alternate hours. Two tracks were laid down composed of soil, brick dust, and sawdust. But the surface seemed more like “potter’s clay” with no spring in it, similar to walking on a carpet. The outer track was seven laps to a mile and the inner, 6.5.

There was a lot of work to be performed behind the scenes to pull over the event. For example, a labor conflict arose when the judges demanded to be paid time-and-a-half for their long hours. Two bands were hired to play from 5 a.m. to midnight and the two walkers would oversee which tunes were played in alternate hours. Two tracks were laid down composed of soil, brick dust, and sawdust. But the surface seemed more like “potter’s clay” with no spring in it, similar to walking on a carpet. The outer track was seven laps to a mile and the inner, 6.5.

A large score board was put up in clear view of the public that would be maintained by four lap-counters. New rules were added to disallow pacing. “Each man must walk alone, and no attendant to be allowed to go more than 25 yards at a time with either competitor, and then only for the purpose of handling refreshments.” The race would adhere to strict walking standards, where they could not have both feet off the ground at the same time.

O’Leary had been training in Holylake, in Cheshire, while Weston was doing long walks in London. Weston had announced that after this race, he would retire from public life. The excitement grew. The wagering on the race was huge, with O’Leary as the slight favorite. No Brits would be competing, “owing to that the Englishmen being invariably out of training.”

Pre-race hype included, “There seems every probability of the match resulting in one of the most exciting contests ever witnessed. O’Leary’s speed will be balanced by Weston’s extraordinary powers of endurance and wonderful ability of resisting that intense feeling of drowsiness generally experienced by all men undergoing long and continued exertion.”

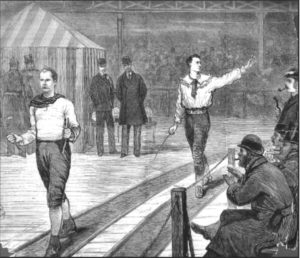

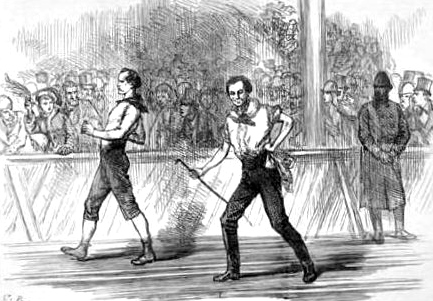

The Start

The much-anticipated Weston-O’Leary race II started at 12:05 a.m., on April 2, 1877, in the Agricultural Hall. O’leary started one minute late for some reason, and both went off at a steady pace. “The attendance to witness the start was more numerous than might have been expected.” Weston walked on the inner track, and O’Leary on the outer. Initially during the early morning, the attendance in the hall was restricted to race officials, handlers, and members of the press. Nearly every newspaper in Great Britain covered the blow-by-blow progress. O’Leary quickly opened a one-mile lead after one hour.

The much-anticipated Weston-O’Leary race II started at 12:05 a.m., on April 2, 1877, in the Agricultural Hall. O’leary started one minute late for some reason, and both went off at a steady pace. “The attendance to witness the start was more numerous than might have been expected.” Weston walked on the inner track, and O’Leary on the outer. Initially during the early morning, the attendance in the hall was restricted to race officials, handlers, and members of the press. Nearly every newspaper in Great Britain covered the blow-by-blow progress. O’Leary quickly opened a one-mile lead after one hour.

As dawn arrived, the gas lights in the building were doused out, and the bands arrived to play. Because it was a bank holiday (the day after Easter), only a sparse crowd arrived. “When the two competitors came near each other, the crowd cheered, and a few shrill whistles accompanied by the cry of ‘Go it, Weston,’ or ‘Go it Leary.’” O’Leary drank some beer that disagreed with him and forced him to make an early stop. For the rest of the race, he ate mostly grapes, figs, and strawberries.

As dawn arrived, the gas lights in the building were doused out, and the bands arrived to play. Because it was a bank holiday (the day after Easter), only a sparse crowd arrived. “When the two competitors came near each other, the crowd cheered, and a few shrill whistles accompanied by the cry of ‘Go it, Weston,’ or ‘Go it Leary.’” O’Leary drank some beer that disagreed with him and forced him to make an early stop. For the rest of the race, he ate mostly grapes, figs, and strawberries.

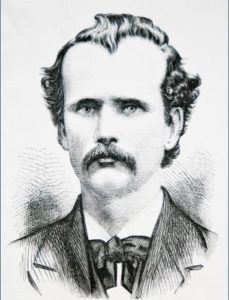

Daniel O’Leary

After 63 miles and 12 hours, O’Leary “was seized with vomiting” and had to stop for nearly an hour. Weston took the lead at that point and reached 100 miles in 20:06:10, and O’Leary arrived there at 20:24:01. It continued to be a very close race. “Large crowds of people continued to come and go, many remaining to watch the two men for a few minutes only. As the evening advanced the crowd thickened and watched with astonishment, mingled with pity for the two men that continued to plod around the hall at a pace which few present would have cared to keep up even for a couple of miles. The crowd, which consisted of the ordinary one seen on all holidays, was mostly orderly, and the police present had absolutely nothing to do but to saunter about and like the rest watch the two men on the path.” When they retired to sleep after the first 24 hours, Weston was at 116.5 miles, to O’Leary’s 114 miles. The attendance for the day was 4,500.

Day Two

Weston

Both walkers did not sleep long, O’Leary about one hour and Weston three hours. They came back out during the wee hours of the morning, “walking quietly on through the deserted hall, in which the only signs of life were the judges’ box and here and there some one nodding in a chair placed in convenient corners.”

O’Leary “turned the tables on Weston” and after 37 hours, was at 163.5 mile to Weston’s 150. “Weston has shown so far, a wonderful power of being able to do without sleep, and this power was counterbalanced by O’Leary’s superior pace when on the track. The difference in the mode of walking was very marked, O’Leary being erect in carriage and moving with a long, graceful strid. Weston’s gait, as usual, was very unattractive.” As O’Leary increased his lead, Weston decided to stick to his schedule and pacing chart. He believed that 506 miles would win the race and he had a solid plan to achieve it. He fueled on strong beef tea, raw eggs beaten up, and jelly.

O’Leary “turned the tables on Weston” and after 37 hours, was at 163.5 mile to Weston’s 150. “Weston has shown so far, a wonderful power of being able to do without sleep, and this power was counterbalanced by O’Leary’s superior pace when on the track. The difference in the mode of walking was very marked, O’Leary being erect in carriage and moving with a long, graceful strid. Weston’s gait, as usual, was very unattractive.” As O’Leary increased his lead, Weston decided to stick to his schedule and pacing chart. He believed that 506 miles would win the race and he had a solid plan to achieve it. He fueled on strong beef tea, raw eggs beaten up, and jelly.

During the evening, there was great excitement as O’Leary was approaching 200 miles. He reached a new world record time of 45:21:33, crushing the old record by more than an hour. “Seldom before, notwithstanding the many exciting scenes witnessed in the Agricultural Hall, has its roof rung to louder shouts than greeted the posting of this fact on the scoring board.” After day two, O’Leary had set a 48-hour world record of 207.5 miles and Weston was at 194 miles, staying out on the track longer until midnight.

During the evening, there was great excitement as O’Leary was approaching 200 miles. He reached a new world record time of 45:21:33, crushing the old record by more than an hour. “Seldom before, notwithstanding the many exciting scenes witnessed in the Agricultural Hall, has its roof rung to louder shouts than greeted the posting of this fact on the scoring board.” After day two, O’Leary had set a 48-hour world record of 207.5 miles and Weston was at 194 miles, staying out on the track longer until midnight.

Day Three

On day three, O’Leary reappeared on the track at 12:30 a.m. and had the track to himself for nearly three hours, stretching his lead to 25 miles. The crowds were growing with each day as they realized that the two were accomplishing big miles and to get a glimpse of these very famous athletes. They commented on the difference between the two. “Oleary is a tall, broad-shouldered man, with high forehead, stern countenance, and in possession of a figure that a sculptor would delight to model. On the other hand, Weston is a thin, wiry, little man, with a peculiar comical look, and whose every movement is suggestive of his limbs being set on springs.”

On day three, O’Leary reappeared on the track at 12:30 a.m. and had the track to himself for nearly three hours, stretching his lead to 25 miles. The crowds were growing with each day as they realized that the two were accomplishing big miles and to get a glimpse of these very famous athletes. They commented on the difference between the two. “Oleary is a tall, broad-shouldered man, with high forehead, stern countenance, and in possession of a figure that a sculptor would delight to model. On the other hand, Weston is a thin, wiry, little man, with a peculiar comical look, and whose every movement is suggestive of his limbs being set on springs.”

People wondered why O’Leary always walked clutching a “corn cob” in each hand during his races. He replied, “I think it is habit as anything else. They probably absorb the perspiration and keep the hands from swelling. In walking, I hold my arms up and work my hands across each other toward the opposite shoulder. I used the cobs at first because a light grip on them seemed to make me solid. That got me into the habit of walking with cobs and I never have been able to break myself of it.”

The band was having a great time. “They happened to be playing the liveliest of tunes, in which a chorus was a sort of barbaric whoo-hoop by the performers as Weston and O’Leary were spurting side-by-side to the intense delight of the spectators, who shouted each name of his favorite, while hail rattled on the roof and thunder rolled overhead at intervals and lightning illuminated the darkened hall.”

The band was having a great time. “They happened to be playing the liveliest of tunes, in which a chorus was a sort of barbaric whoo-hoop by the performers as Weston and O’Leary were spurting side-by-side to the intense delight of the spectators, who shouted each name of his favorite, while hail rattled on the roof and thunder rolled overhead at intervals and lightning illuminated the darkened hall.”

There was concern whether O’Leary was getting much sleep. “Many have noticed that his face denotes mental, rather than bodily fatigue. Weston is naturally of a lively and cheerful disposition and jokes with the bystanders as he walks around the hall, while O’Leary has a stern look.” For 72 hours, O’Leary set a new world record of 294 miles, while Weston was credited with 274.5.

Day Four

On day four, the spectators still were not certain about who would win the race. O’Leary increased his lead back to 25 miles, but Weston was expected to catch up. It became evident that O’Leary was starting to struggle dangerously, and his attendants strongly urged him to stop for some rest. He refused and “motioned his friend away with a wave of his arm.” But he finally stopped in the early afternoon with 350 miles, and a 27-mile lead. He fell into a deep sleep for about four hours. Weston continued and cut 15 miles into that lead before O’Leary returned.

On day four, the spectators still were not certain about who would win the race. O’Leary increased his lead back to 25 miles, but Weston was expected to catch up. It became evident that O’Leary was starting to struggle dangerously, and his attendants strongly urged him to stop for some rest. He refused and “motioned his friend away with a wave of his arm.” But he finally stopped in the early afternoon with 350 miles, and a 27-mile lead. He fell into a deep sleep for about four hours. Weston continued and cut 15 miles into that lead before O’Leary returned.

In the evening, the crowd was bigger than ever. Those in the middle of hall would run across the oval to watch the two men each time they came anywhere close to each other. At times during a lively tune of the band, Weston would put on spurts and onlookers commented that it looked like he was running. “O’Leary walks on with stolid face, perfectly unmoved by the applause of the lookers-on, and is not so easily temped to spurting.” One of the judges objected to Weston’s style and requested that one lap be taken from him, but the objection was overruled by the other judges. After four days, O’Leary reached 370 miles to Weston’s 353. In wager odds, O’Leary had become a 7-4 favorite.

In the evening, the crowd was bigger than ever. Those in the middle of hall would run across the oval to watch the two men each time they came anywhere close to each other. At times during a lively tune of the band, Weston would put on spurts and onlookers commented that it looked like he was running. “O’Leary walks on with stolid face, perfectly unmoved by the applause of the lookers-on, and is not so easily temped to spurting.” One of the judges objected to Weston’s style and requested that one lap be taken from him, but the objection was overruled by the other judges. After four days, O’Leary reached 370 miles to Weston’s 353. In wager odds, O’Leary had become a 7-4 favorite.

Day Five

O’Leary continued on very steadily on day five. When it was his turn to oversee the band tunes, he chose to have them not play at all because the music made Weston increase his speed. When one of the walkers was off the track, the band was also not allowed to play to let the walker sleep. O’Leary was pretty devious, planning his rests during an hour when Weston had control of the band, but was then not allowed to let them play.

The crowd was huge. “There was about 5,000, and the inner circle was crowded, several ladies being present, who evidently took a keen interest in the proceedings. Weston, although limping and evidently fatigued, would not stop, and determined to try and wear his opponent down.” At the end of day five, O’Leary had a lead of 14.5 miles – 453.5 to 439. O’Leary walked 86 miles that day to Weston’s 84.

The crowd was huge. “There was about 5,000, and the inner circle was crowded, several ladies being present, who evidently took a keen interest in the proceedings. Weston, although limping and evidently fatigued, would not stop, and determined to try and wear his opponent down.” At the end of day five, O’Leary had a lead of 14.5 miles – 453.5 to 439. O’Leary walked 86 miles that day to Weston’s 84.

Final Day

The attendance was enormous on the final day, with more than 20,000 going through the turnstiles, even though the price of admission had strategically been raised. “We question if any walking match has ever excited so much general interest as this one. Pedestrianism, as a rule, is not a sport about which the public concern themselves a great deal, but the magnitude of the present undertaking forced itself upon their attention.”

The attendance was enormous on the final day, with more than 20,000 going through the turnstiles, even though the price of admission had strategically been raised. “We question if any walking match has ever excited so much general interest as this one. Pedestrianism, as a rule, is not a sport about which the public concern themselves a great deal, but the magnitude of the present undertaking forced itself upon their attention.”

By noon, it was very evident that Weston would not be able to catch O’Leary who had a 17-mile lead. But O’Leary also was suffering during the morning with a badly pained left shoulder that caused him to do the “ultra-lean” to the left for a while. When he reached 498 miles, Sir John Astley, Weston’s backer, told O’Leary’s backers that they could stop the race if they wanted, that Weston was defeated. He later said that Weston had been weeping and could barely move. But there was no way O’Leary wanted to stop.

By noon, it was very evident that Weston would not be able to catch O’Leary who had a 17-mile lead. But O’Leary also was suffering during the morning with a badly pained left shoulder that caused him to do the “ultra-lean” to the left for a while. When he reached 498 miles, Sir John Astley, Weston’s backer, told O’Leary’s backers that they could stop the race if they wanted, that Weston was defeated. He later said that Weston had been weeping and could barely move. But there was no way O’Leary wanted to stop.

At 1:50 p.m. O’Leary crossed the 500-mile mark, setting a new world time record for that distance. “The cheering and excitement when the board announced his 500th mile baffles all description. Many of those inside the enclosure ran around with O’Leary waving their hats and handkerchiefs.” His friend, a Catholic priest, who was seated on a chair outside his tent, calmly whispered a few words of encouragement to him. Some estimated there were 35,000 people watching the final hours of the race.

Once O’Leary exceeded his own world record 503 miles in six days, he looked very shaky, so his attendants took him off the track for a rest. He “reeled off the track into the arms of his attendants” and the crowd went wild with enthusiasm. When he returned about 35 minutes later, his pace was very slow, and he took more rests. Weston passed 500 miles at 8:15 p.m. Curiously, he then pushed a garden roller in front of him, assisting him to walk. Near the end, O’Leary came out wearing an overcoat and walked two laps with his backer Hague and another friend. But since pacers were not allowed, those two laps were stricken from his total.

Once O’Leary exceeded his own world record 503 miles in six days, he looked very shaky, so his attendants took him off the track for a rest. He “reeled off the track into the arms of his attendants” and the crowd went wild with enthusiasm. When he returned about 35 minutes later, his pace was very slow, and he took more rests. Weston passed 500 miles at 8:15 p.m. Curiously, he then pushed a garden roller in front of him, assisting him to walk. Near the end, O’Leary came out wearing an overcoat and walked two laps with his backer Hague and another friend. But since pacers were not allowed, those two laps were stricken from his total.

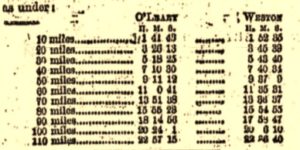

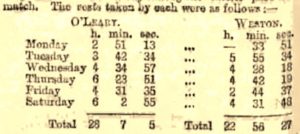

Rest Times

The crowd was very impressed with Weston’s solid finish with honor, lapping O’Leary many times when he knew that he could not win. Both quit with about an hour to go. The final historic tally at the end of the six days was O’Leary 519 miles 1585 yards, a new world record, to Weston’s 510. The totals for rest time were 28:07:05 for O’Leary and 22:56:27 for Weston. O’Leary claimed that he only slept for eight total hours and never ate any solid food. He fueled mostly on fruits, grapes, figs, and strawberries.

“O’Leary was presented with no less than six bouquets by lady admirers, whilst Weston received three. Weston, upon leaving the track, entered a cab and drove away at once, thus disappointing the spectators that expected him to, as usual, make a speech.” O’Leary stayed and thanked the judges and officials for the fair race they conducted. He also thanked Weston, because if it had not been for him, he would have never known his own power.

“O’Leary was presented with no less than six bouquets by lady admirers, whilst Weston received three. Weston, upon leaving the track, entered a cab and drove away at once, thus disappointing the spectators that expected him to, as usual, make a speech.” O’Leary stayed and thanked the judges and officials for the fair race they conducted. He also thanked Weston, because if it had not been for him, he would have never known his own power.

Weston recovered quickly and went out for a walk the next morning. O’Leary stayed on a sofa with a sore foot and a terribly blistered heel. Just like their first race, Weston excuses later came out. He said that he experienced an accident on day two that ruined his race. He also severely underestimated how much O’Leary had improved since their first race. He quickly challenged O’Leary for another rematch to be held in a month. It did not happen.

Reaction and Impact

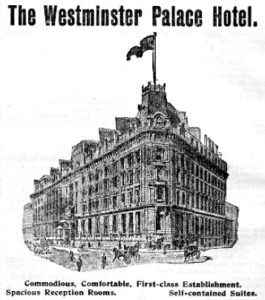

A couple weeks later, Irish members of Parliament held a grand banquet to honor Oleary at the Westminster Palace Hotel. They did not invite Weston. About 140 prominent men attended. A flattering toast was given to him and then he said, “there are thousands of my countrymen in Ireland who had done much more to deserve praise than what I have done. If I could only talk as well as I can walk, I might do justice to the flattering cheers of my new friends, but I cannot and can only pledge my honor that I felt prouder at this tribute than ever before.”

A couple weeks later, Irish members of Parliament held a grand banquet to honor Oleary at the Westminster Palace Hotel. They did not invite Weston. About 140 prominent men attended. A flattering toast was given to him and then he said, “there are thousands of my countrymen in Ireland who had done much more to deserve praise than what I have done. If I could only talk as well as I can walk, I might do justice to the flattering cheers of my new friends, but I cannot and can only pledge my honor that I felt prouder at this tribute than ever before.”

Weston in England

The English were impressed. “These American pedestrians both have extraordinary endurance, capable of walking distances that have taken most persons by surprise and quite revolutionized pedestrianism in this country. O’Leary performed a task that a few years back was thought as incredible and as improbable as the feat of swimming the English Channel.”

There were also critics. “The illogical law permits thousands of people to assemble, and thousands of shillings to be paid at the Agricultural Hall whilst a couple of madmen, under the pretense of sport, shorten the lives allotted to them in the presence of the police as surely as do suicides from the bridges of the Thames.” (Weston lived to be 90, and Oleary reached 86. Normal life expectancy at the time was about 60).

The race deeply impacted Sir John Astley who crewed Weston and had only about 2-3 hours of sleep per day. He said, “I never was more excited over any performance and the number of cigars I went through was a record.” It is believed that Astley lost a huge amount of money on the race, but the experience resulted in his deep enthusiasm for the sport. He would take it to levels that would have been impossible without him.

After visiting his Irish homeland, O’Leary boarded the steamer Wisconsin on May 12, 1877, and arrived back America on May 24th, richer by about 14,000(about14,000 (about 14,000(about375,000 value today). Years later he pointed to this race as being the highpoint of his pedestrian career. Four months later during September 1877, in St. Louis, Missouri, he reached 513 miles, reaching 500+ miles in six-days for the sixth time in a race against two St. Louis, Missouri amateur walkers, Orin W. Beckwith (1851-1915), a telephone operator and Charles Hottes (1854-1884), a clerk born in Germany, who together reached 494.8 miles. Score one for the amateur’s effort. “They really accomplished wonders for amateurs and were only beaten after a plucky struggle by an unbeatable man.

After visiting his Irish homeland, O’Leary boarded the steamer Wisconsin on May 12, 1877, and arrived back America on May 24th, richer by about 14,000(about14,000 (about 14,000(about375,000 value today). Years later he pointed to this race as being the highpoint of his pedestrian career. Four months later during September 1877, in St. Louis, Missouri, he reached 513 miles, reaching 500+ miles in six-days for the sixth time in a race against two St. Louis, Missouri amateur walkers, Orin W. Beckwith (1851-1915), a telephone operator and Charles Hottes (1854-1884), a clerk born in Germany, who together reached 494.8 miles. Score one for the amateur’s effort. “They really accomplished wonders for amateurs and were only beaten after a plucky struggle by an unbeatable man.

Weston stayed in England for more than two years, licking his wounded pride, and having mixed success in additional walking exhibitions. With O’Leary gone, there was weaker competition in England compared to America, and more money to win. It made sense for him to stay.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultra-marathoning: The Next Challenge

- The Wilmington Morning Star (North Carolina), Nov 3, 1876

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Oct 15, 1876, Jan 21, 1877

- The Cheltenham Chronicle and Parish Register (Gloucestershire, England), Oct 3, 1876

- Liverpool Daily Post (Liverpool, England), Apr 12, Oct 14-23, 1876, Feb 2-3, 5 1877

- Liverpool Mercury (England), Oct 19, 21, 23, 1876

- The Leicester Daily Mercury (England), Dec 19, 1876

- Daily News (London, England), Dec 20, 1876, Apr 5, 1877

- Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (England), Dec 20, 1876

- The East Kent Gazette (England), Dec 23, 1876

- Reynold’s Newspaper (London, England), Dec 24, 1876

- The Birmingham Daily Mail (England), Dec 26, 1876, Jan 6, 1877

- Chester Chronicle (England), Dec 30, 1876

- The Nottinghamshire Guardian (England), Jan 5, 1877

- Jackson’s Oxford Journal (Oxford, England), Jan 6, 1877

- Chestershire Observer (England), Jan 6, 1877

- Manchester Evening News (England), Nov 21-24, 1876, Jan 8, Apr 2, 7, 1877

- The Yorkshire Herald (England), Jan 11, Mar 5, 1877

- The Huddersfield Chronicle (West Yorkshire, England), Jan 23, 1877

- The Sportsman (London, England), Jan 30, Apr 2, 1877

- Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (London, England), Mar 4, Apr 8, 1877

- Glasgow Herald (Scotland), Mar 5, 12, 1877

- Edinburgh Evening News (Scotland), Mar 6-12, 1877

- Falkirk Herald (Scotland), Mar 17, 1877

- Sporting Life (London, England), Mar 31, 1877

- The Standard (London, England), Apr 2-6, 9 1877

- Islington Gazette (London, England), Apr 4, 1877

- The Guardian (London, England), Apr 2, 8 1877

- Citizen (Gloucester, England), Apr 3, 9, 1877

- The Daily Telegraph (London, England), Apr 3, 1877

- Manchester Courier (England), Apr 3, 1877

- Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (England), Apr 4-5, 1877

- The North-Eastern Daily Gazette (Middlesbrough, England), Apr 6, 1877

- The Penny Illustrated Paper (London, England), Apr 7, 1877

- The Observer (London, England), Apr 8, 1877

- The Boston Globe (Massachusetts), Apr 10, 1877

- Dublin Evening Telegraph (Ireland), Apr 26, 1877

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch (Missouri), Sep 3-10, 1877

- The Atchison Daily Champion (Kansas), Sep 11, 1877