Edward Payson Weston and Daniel O'Leary race for six days in 1875 in Chicago (original) (raw)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 23:29 — 27.8MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

You can read, listen, or watch

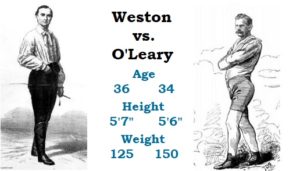

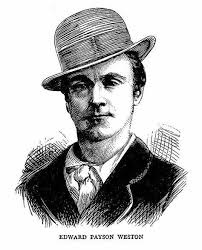

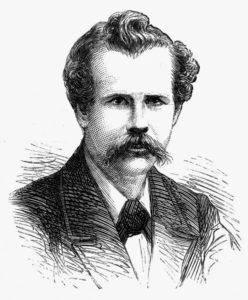

In 1875, Edward Payson Weston was the most famous ultrarunner (pedestrian) in the world. Like a heavyweight boxing champion dodging his competition to keep his crown, he avoided repeated challenges to race against the up-and-comer, Daniel O’Leary of Chicago, Illinois. The two were the most famous American athletes in 1875.

In 1875, Edward Payson Weston was the most famous ultrarunner (pedestrian) in the world. Like a heavyweight boxing champion dodging his competition to keep his crown, he avoided repeated challenges to race against the up-and-comer, Daniel O’Leary of Chicago, Illinois. The two were the most famous American athletes in 1875.

During August 1875, it was announced in New York City that plans were unfolding to hold “a grand international pedestrian tournament” in October that would include a six-day race with $1,000 going to the winner. It was hoped that all the great pedestrians including Weston and O’Leary would compete. Unfortunately, that race never unfolded, but Weston and O’Leary would soon battle head-to-head, not in New York City, but on O’Leary’s turf in Chicago.

During August 1875, it was announced in New York City that plans were unfolding to hold “a grand international pedestrian tournament” in October that would include a six-day race with $1,000 going to the winner. It was hoped that all the great pedestrians including Weston and O’Leary would compete. Unfortunately, that race never unfolded, but Weston and O’Leary would soon battle head-to-head, not in New York City, but on O’Leary’s turf in Chicago.

Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a few dollars each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member

Weston vs. O’Leary – Finally

Finally, on October 30, 1875, it was announced that Weston and O’Leary would compete in a six-day race on November 15th, with 5,000goingtothewinnerand5,000 going to the winner and 5,000goingtothewinnerand2,500 to the loser. O’Leary’s men had approached Weston offering 500extratocoverhisexpenses.ItwasjusttoomuchmoneyforWestontoresist,potentiallyabout500 extra to cover his expenses. It was just too much money for Weston to resist, potentially about 500extratocoverhisexpenses.ItwasjusttoomuchmoneyforWestontoresist,potentiallyabout140,000 in today’s value if he won.

Finally, on October 30, 1875, it was announced that Weston and O’Leary would compete in a six-day race on November 15th, with 5,000goingtothewinnerand5,000 going to the winner and 5,000goingtothewinnerand2,500 to the loser. O’Leary’s men had approached Weston offering 500extratocoverhisexpenses.ItwasjusttoomuchmoneyforWestontoresist,potentiallyabout500 extra to cover his expenses. It was just too much money for Weston to resist, potentially about 500extratocoverhisexpenses.ItwasjusttoomuchmoneyforWestontoresist,potentiallyabout140,000 in today’s value if he won.

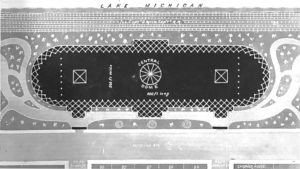

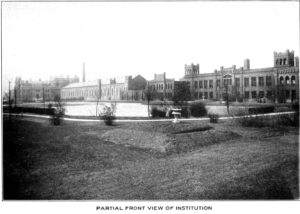

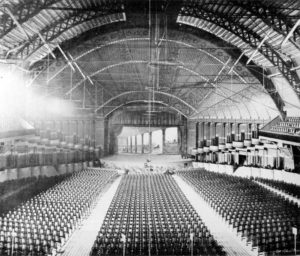

The venue would be in the massive new Interstate Exposition Building in Chicago. The building, measuring 800×400 feet, had opened in 1873, just two years after the Great Chicago Fire. It was rented with promises of receiving 15% of gross gate receipts.

The venue would be in the massive new Interstate Exposition Building in Chicago. The building, measuring 800×400 feet, had opened in 1873, just two years after the Great Chicago Fire. It was rented with promises of receiving 15% of gross gate receipts.

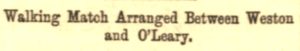

The announcement created great excitement across the country. To many at the time, it was similar to the dream matchup between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier in 1971, regarded as the greatest boxing match in history.

The announcement created great excitement across the country. To many at the time, it was similar to the dream matchup between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier in 1971, regarded as the greatest boxing match in history.

However, there were critics against holding the event. In Ottawa, Illinois it was written, “What excites our wonderment is, who pays the $7,500? What benefit can it be to anybody whether they walk 100 or 1,000 miles in six days. A horse or mule able to walk 600 miles in six days might be worth something, but who cares how many miles Weston or O’Leary can walk in a day or month, so long as they don’t kill themselves?”

However, there were critics against holding the event. In Ottawa, Illinois it was written, “What excites our wonderment is, who pays the $7,500? What benefit can it be to anybody whether they walk 100 or 1,000 miles in six days. A horse or mule able to walk 600 miles in six days might be worth something, but who cares how many miles Weston or O’Leary can walk in a day or month, so long as they don’t kill themselves?”

Similarly, in Mobile, Alabama: “Suppose these men had ploughs, wouldn’t they add something in this way to the wealth of the world?”

Pre-Race

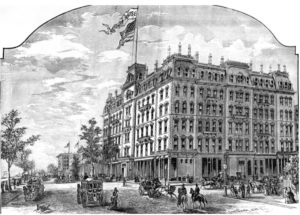

Gardner House

Weston arrived in Chicago three days before the race with his two black servants and stayed at the luxurious Gardner House, next to the Exposition Building on the Lake Michigan lakefront. It was reported, “He is in good condition and confident of success. O’Leary also is in excellent trim, and confident of victory as his opponent. The contest will no doubt prove very exciting.” Wagering was heavy with Weston being a slight favorite.

Exposition Building Map

The Chicago Tribune gave a pre-race commentary about the two pedestrians. “O’Leary has made some excellent feats, and has but one failure to his credit, while Weston, with also a good record at times, has a considerable number of bad fizzles on his list of attempts. Both men have before attempted the 500-mile walk, and both have succeeded. O’Leary made the distance in a little over 153 hours, while Weston covered the same ground in ten hours less. However, some doubt was cast on the accuracy of the timing and measurements which resulted.”

O’Leary visited Weston and talked over plans for the race. Weston inspected the track and gave his approval. Two separate tracks would be used, the outer six laps to a mile, and the inner, seven laps to a mile. Weston was offered his choice and he picked the inside track.

The Start

Spectators began to assemble in the building an hour before the start. There wasn’t a huge crowd, only about 100 people, and consisted mostly of men interested in sports. A reporter visited O’Leary in his room on the east side of the building where he lay on a lounge covered with blankets. His wife was there along with friends and a doctor. O’Leary had at first intended to walk 100 miles in first 18 hours, and 118 miles in the first 24 hours, but changed his strategy to simply aim to beat Weston.

Spectators began to assemble in the building an hour before the start. There wasn’t a huge crowd, only about 100 people, and consisted mostly of men interested in sports. A reporter visited O’Leary in his room on the east side of the building where he lay on a lounge covered with blankets. His wife was there along with friends and a doctor. O’Leary had at first intended to walk 100 miles in first 18 hours, and 118 miles in the first 24 hours, but changed his strategy to simply aim to beat Weston.

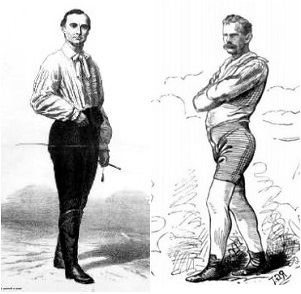

Weston arrived later and came up to the judges’ stand at midnight. O’Leary soon joined him, and a crowd gathered around to watch the start and gave loud applause. The two athletes shook hands and wished each other well. “Weston wore the black velvet suit he has used in his previous matches, knee pants, boots, a light linen hat, a silk ribbon thrown across his shoulders, white gloves, and carried a light whip in his hand. O’Leary wore white tights, a striped tunic, and light walking shoes. He wore no hat and carried a pine stick in each hand.” O’Leary’s wife stood near his track with a nervous look on her face.

William Curtis

William Buckingham Curtis (1837-1900) was the race referee. He was one of the most important proponents of organized athletics in the late 1800s in America and founded the New York Athletic Club and the Chicago Athletic Club.

Mayor Harvey Colvin

Mayor Harvey Doolittle Colvin (1815-1892), the starter, gave a short speech. He hoped that the city would treat the visiting Weston well. “If our man can beat him, or course we shall be very happy, we wouldn’t like it to be done in any unfairness whatever.” The two walkers took their places on their tracks.

Mayor Colvin counted, “one, two, three” and off they went. The second six-day race in history began at 12:08:19 a.m. on November 15, 1875.

Day One

O’Leary shot out fast, completing the first mile in 11:03, with Weston in 12:46. After that, O’Leary settled into a steadier pace and after two miles, they were just 6 seconds apart. The two walkers plodded around during the early morning and didn’t take a rest until mid-morning when O’Leary, in the lead, reached 50 miles in 9:23:50. He then went off the track for 27 minutes. On his return he was often accompanied by his handlers who helped pace him. Weston was much slower but didn’t take long rests and continued at a steady pace. At mile 60 at noon (12 hours), O’Leary had just a two-mile lead. Weston took his first rest of only 11 minutes at mile 76.

O’Leary shot out fast, completing the first mile in 11:03, with Weston in 12:46. After that, O’Leary settled into a steadier pace and after two miles, they were just 6 seconds apart. The two walkers plodded around during the early morning and didn’t take a rest until mid-morning when O’Leary, in the lead, reached 50 miles in 9:23:50. He then went off the track for 27 minutes. On his return he was often accompanied by his handlers who helped pace him. Weston was much slower but didn’t take long rests and continued at a steady pace. At mile 60 at noon (12 hours), O’Leary had just a two-mile lead. Weston took his first rest of only 11 minutes at mile 76.

The walking styles of the two competitors were quite different. O’Leary walked straight, with a quick stride and bent arms. “He conveys the impression of walking nervously with more exertion than Weston and his crooked arm helps to give him an air of labor.” Weston seemed to drag his feet, then throw them, with a long swinging step, with his arms at his sides.” O’Leary held his head up, looking around him, while Weston always looked sharply down and saw nothing but the dirt ahead of him.

During the afternoon, the crowd grew to about 500 and they were allowed to remain on the floor, close to the action. In the evening, the assemblage grew significantly, especially with ladies. “A band was in presence a portion of the day and evening and played rather dolefully but very loud music at intervals, such as the wind of the performers dictated.”

During the afternoon, the crowd grew to about 500 and they were allowed to remain on the floor, close to the action. In the evening, the assemblage grew significantly, especially with ladies. “A band was in presence a portion of the day and evening and played rather dolefully but very loud music at intervals, such as the wind of the performers dictated.”

How did Chicago treat the visiting and controversial Weston? He was treated well during the race with one exception. “Once, a man used insulting language to him as he passed. He at once stopped his travel and demanded of his competitor that the man be cast forth, and the act was accomplished without harm by the police.” A large contingent of police was in attendance doing crowd control, driving back the crowd from time to time.

How did Chicago treat the visiting and controversial Weston? He was treated well during the race with one exception. “Once, a man used insulting language to him as he passed. He at once stopped his travel and demanded of his competitor that the man be cast forth, and the act was accomplished without harm by the police.” A large contingent of police was in attendance doing crowd control, driving back the crowd from time to time.

Bridwell House of Corrections

During that first evening, there was a surprising skirmish in the audience. Fifteen-year-old Albert Henry Morton (1860-1893) had recently escaped from the Bridwell House of Corrections and showed up to watch the race. A police officer noticed him in the crowd and approached to make the arrest. “Albert drew a razor and attempted to carve the officer. A well-directed blow with a club subjugated Albert.” He was taken before a judge and had 90 days added to his ten-month sentence for burglary and stealing a watch and chain. (Morton continued his life of crime for a couple years during his youth after being released from prison, but eventually became a respected businessman in the city. He died young from tuberculosis.)

O’Leary reached 100 miles in 20:58:21, with rests totaling about two and a half hours. At 110 miles, he was 20 miles ahead of Weston and retired to his room for a few hours’ sleep. At that point Weston went to his room at the Gardner House for five hours of sleep. With both men away from the track at 11:30 p.m., most of the crowd to left for the night.

Day Two

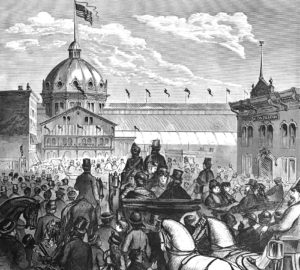

Exposition Building Interior

On the morning of day two, both of the determined walkers were back on the track by 4 a.m. and put in constant miles without any long rests during the day. Weston stopped for a supper break at 5:17 p.m. after reaching his 150th mile.

During the evening, a rumor was circulating around the city that Weston had “broken down” and had resigned from the race. People started to flock to the building to celebrate O’Leary’s victory. A reporter went to Gardner House to validate the report. Weston had just finished his supper and was angry about the false report. He stated that he was not thinking about quitting, that his physical condition was good and he was pleased with his progress.

Weston returned to the track after his supper and continued to walk all evening. He made efforts to please the audience with gestures, songs, imitating actors, and “other recreations.” He claimed that he never felt better and reached mile 168 by midnight. O’Leary stopped for the night at 10:30 p.m. after reaching mile 190. It was speculated that Weston was playing a “waiting game,” expecting that O’Leary would crumble by day four or five. But O’Leary had walked strongly that day and at no time showed any signs of exhaustion.

Day Three

After three hours of sleep, on day three, O’Leary returned to the track at 1:30 a.m. About dawn he experienced a bad nosebleed and needed to stop for an hour to take care of it. Weston had continued his walk until 2 a.m. and after four hours sleep began again at 6 a.m. looking strong.

After three hours of sleep, on day three, O’Leary returned to the track at 1:30 a.m. About dawn he experienced a bad nosebleed and needed to stop for an hour to take care of it. Weston had continued his walk until 2 a.m. and after four hours sleep began again at 6 a.m. looking strong.

During the morning, a man came into the building and handed a note to one of O’Leary’s handlers. It was a formal challenge for O’Leary to walk 150 miles against the man. “The challenge was consigned to the flames.”

The audience size grew each day. Reporters issued complaints that the race staff were providing them “abominable accommodations” being jammed into the crowd without seats, despite the free coverage they were giving in their papers about the event. They said, “It was impossible for newspaper men to make reports while hanging over a railing to which their chins barely reach.”

O’Leary extended his lead by five miles that day. The score at midnight was O’Leary 273 miles, Weston 247 miles.

Day Four

How were the two walkers doing on day four? “O’Leary wears the same thoughtful look that has characterized him during the contest, while Weston keeps up that jolly good humor for which he is noted.” Another observer remarked that “O’Leary looked somewhat hollow-eyed and weary-looking in the face, but still was perfectly self-possessed, and sometimes would stop or dawdle around in the coolest manner possible, stopping to chat and exchange salutations with his friends.”

How were the two walkers doing on day four? “O’Leary wears the same thoughtful look that has characterized him during the contest, while Weston keeps up that jolly good humor for which he is noted.” Another observer remarked that “O’Leary looked somewhat hollow-eyed and weary-looking in the face, but still was perfectly self-possessed, and sometimes would stop or dawdle around in the coolest manner possible, stopping to chat and exchange salutations with his friends.”

Mayor Covin put in an appearance during the day and walked with Weston around the track a few times. It was commented, “A few laps were sufficient to show that he does not shine with any particular brilliancy as a walker.”

At 11:40 p.m. O’Leary said as he passed the judges’ stand and shouted, “Gentlemen, I bid you all good night.” He had reached 350 miles. Weston continued until midnight, reaching 314 miles. Each day O’Leary was increasing his lead.

Day Five

During the evening of day five, the throng was amazing. “The attendance was simply immense. The floors and galleries were densely thronged, and at a moderate calculation, there could not have been less than 8,000 people present, among them many ladies. Both the pedestrians were warmly cheered as they proceeded on their weary round.” Weston reached 390 miles and O’Leary was at 425 miles.

During the evening of day five, the throng was amazing. “The attendance was simply immense. The floors and galleries were densely thronged, and at a moderate calculation, there could not have been less than 8,000 people present, among them many ladies. Both the pedestrians were warmly cheered as they proceeded on their weary round.” Weston reached 390 miles and O’Leary was at 425 miles.

Day Six

On the final day, O’Leary started his walk at 4:30 a.m. looking as well as could be expected. He walked very steadily all day and did not show fatigue. Weston started at the same time but not looking fresh and retired after only forty minutes for another rest.

On the final day, O’Leary started his walk at 4:30 a.m. looking as well as could be expected. He walked very steadily all day and did not show fatigue. Weston started at the same time but not looking fresh and retired after only forty minutes for another rest.

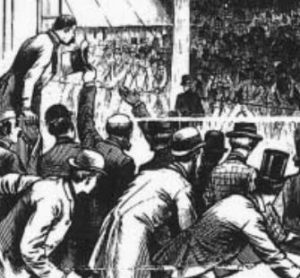

The scene of the last day in the Exposition Building was astonishing and hard to imagine. It was packed with a lengthy line of people waiting on the street to reach the ticket office. Men going home from work, dropped by to see how thing were going. In the evening, the “rush” was said to be unparalleled. “The approaches to the building were surrounded by a surging mass of humanity, eager to procure tickets. Excitement could not have reached a higher pitch, almost a wild delirium.”

The scene of the last day in the Exposition Building was astonishing and hard to imagine. It was packed with a lengthy line of people waiting on the street to reach the ticket office. Men going home from work, dropped by to see how thing were going. In the evening, the “rush” was said to be unparalleled. “The approaches to the building were surrounded by a surging mass of humanity, eager to procure tickets. Excitement could not have reached a higher pitch, almost a wild delirium.”

“The crowd was dense, sweeping hither and thither, shouting, yelling, or cheering. The crowd represented wealth, brains, thieves, gamblers, and roughs. Ladies were there in large numbers, but all had a terribly hard time of it in the ceaselessly moving and noisy throng.” It was amazing to see dignified gentlemen in neckties, standing next to those of the lower class, cheering together.

The police had trouble managing the crowd and at times were overwhelmed by mobs coming down on the track composed of gamblers, thieves, pickpockets, and rowdies. There was an estimated 8,000 people in the building, most of which were orderly working men with wives and children. Many boys and men climbed for high perches in the building trusses near the roof, on top of the large town clock and elevator. “Though the crowd made a great deal of noise, it was very good-natured, and though it felt pleased with O’Leary’s feat, it did not forget to heartily cheer the New York lad.”

At 7:55 p.m. O’Leary had reached his 488th mile, while Weston had only walked 14 miles so far that day and was at 439 miles. As O’Leary continued to close in on 500 miles, the crowd cheered loudly as he went by. He stopped at 8 p.m., was rubbed down and drank hot tea. Even though Weston was beat, he was encouraged on with cries of “bully boy” and “go in.” It was announced that O’Leary planned to walk past 500 miles and go as far as he could before midnight.

The Finish

After O’Leary reached his 497th mile, chaos ensued. “At this time the crowd seized the track and was driven back with the greatest difficulty.” Many went through the ropes to gather between the tracks used by the walkers. Weston looked very weary and dejected but kept plodding along. O’Leary clocked a 13:15 mile for his 499th mile. “As he neared the judges’ stand on this 500th mile, a terrific cheer rent the air, hats flew up, the band played, and the pedestrian’s wife presented him with a magnificent basket of flowers.” He reached 500 miles in a world record 143 hours, 13 minutes. He then continued and set a new six-day world record of 503 miles. Weston reached 451 miles.

After O’Leary reached his 497th mile, chaos ensued. “At this time the crowd seized the track and was driven back with the greatest difficulty.” Many went through the ropes to gather between the tracks used by the walkers. Weston looked very weary and dejected but kept plodding along. O’Leary clocked a 13:15 mile for his 499th mile. “As he neared the judges’ stand on this 500th mile, a terrific cheer rent the air, hats flew up, the band played, and the pedestrian’s wife presented him with a magnificent basket of flowers.” He reached 500 miles in a world record 143 hours, 13 minutes. He then continued and set a new six-day world record of 503 miles. Weston reached 451 miles.

After stopping, O’Leary waited on the track for Weston to finish and then the crowd surrounded them both as they made several turns of the track together. O’Leary was then presented with a massive gold medal as champion of the world, and then the two men were taken safely away from the crowd.

After stopping, O’Leary waited on the track for Weston to finish and then the crowd surrounded them both as they made several turns of the track together. O’Leary was then presented with a massive gold medal as champion of the world, and then the two men were taken safely away from the crowd.

The event was a great financial success, bringing in about 16,000fortheweek,valuedat16,000 for the week, valued at 16,000fortheweek,valuedat400,000 in today’s value. Later, O’Leary said that he and Weston divided the net gate proceeds, each receiving $5,500. They both became very wealthy. O’Leary would invest much of it back into the sport. Weston would spend most of it on an extravagant lifestyle, always spending more than he earned.

Post-Race

The next evening, a reporter went to interview Weston at his room in Gardner House. Weston looked “fresh as a schoolboy after a vacation.” He took his shoes and socks off and showed everyone that his feet had no blisters or bruises. Weston talked about his loss in the race. He wished that he would have pushed to walk 100 miles on the first day when fresh and wished he had slept on the Sunday before the race. He explained that he was too nervous to go to sleep.

The next evening, a reporter went to interview Weston at his room in Gardner House. Weston looked “fresh as a schoolboy after a vacation.” He took his shoes and socks off and showed everyone that his feet had no blisters or bruises. Weston talked about his loss in the race. He wished that he would have pushed to walk 100 miles on the first day when fresh and wished he had slept on the Sunday before the race. He explained that he was too nervous to go to sleep.

Then came an excuse. The fumes from the furnace of a peanut stand bothered him, got into his head, and affected his sleep during the race. He said, “The gas from the charcoal got into my head though I did not notice it at the time.”

Then came an excuse. The fumes from the furnace of a peanut stand bothered him, got into his head, and affected his sleep during the race. He said, “The gas from the charcoal got into my head though I did not notice it at the time.”

When asked about O’Leary, he said he was the fastest walker he had ever met, but he still believed he could beat him in a very long race, even though he did not this time. Months later, after Weston was frustrated with continual reminders about his defeat by O’Leary, he brought forth a new excuse that was never reported on during the race. He said that some Chicagoans had sprayed pepper in this face as he walked, and others threatened to shoot him. This was likely untrue and just sour grapes for not performing as well as he hoped.

The reporter next visited O’Leary in his home, a modest little furniture store, where the family lived in the rear. O’Leary was cheerful and chatty and didn’t seem to be fazed by his efforts during the past week. He said that he had slept only a total of sixteen hours during the entire week. While he stopped more often than Weston, he was convinced that his speed could win the walk. Once he established a big lead, he didn’t see any reason to be in a big hurry and held back.

The reporter next visited O’Leary in his home, a modest little furniture store, where the family lived in the rear. O’Leary was cheerful and chatty and didn’t seem to be fazed by his efforts during the past week. He said that he had slept only a total of sixteen hours during the entire week. While he stopped more often than Weston, he was convinced that his speed could win the walk. Once he established a big lead, he didn’t see any reason to be in a big hurry and held back.

Of Weston, O’Leary said, “He is an extraordinary man. He can endure more hardship than any man I have ever seen. His method of walking is one that I wouldn’t make any criticism upon it. But if I were to walk as he does. I know I could not endure for a day.”

Of Weston, O’Leary said, “He is an extraordinary man. He can endure more hardship than any man I have ever seen. His method of walking is one that I wouldn’t make any criticism upon it. But if I were to walk as he does. I know I could not endure for a day.”

O’Leary started to receive challenges from random unknown walkers, which he ignored. A rumor was going around that he and Weston were going to form a partnership and go on tour, but he said that report was false. He was willing to walk against him or any other man if the money was worth it, but at that time, he didn’t plan to compete for the next six months. He believed that someday he would compete in England.

Reaction to the Race

As could be expected, Chicago gloated over the victory. The Chicago Tribute cheered, “The Chicago boy has shown that his powers of endurance and strength are greater than those of the man from New York and has proved himself a champion and won the title of the champion pedestrian of the world. O’Leary retired with baskets of flowers and a huge gold medal, while Weston retired with nothing to speak of but the lead he put in his boots, his ruffled shirt and green trimmings, and the remembrance of his folly in supposing that, after dilly-dallying along for three or four days, that he could make up the difference on the last day and come out ahead.”

As could be expected, Chicago gloated over the victory. The Chicago Tribute cheered, “The Chicago boy has shown that his powers of endurance and strength are greater than those of the man from New York and has proved himself a champion and won the title of the champion pedestrian of the world. O’Leary retired with baskets of flowers and a huge gold medal, while Weston retired with nothing to speak of but the lead he put in his boots, his ruffled shirt and green trimmings, and the remembrance of his folly in supposing that, after dilly-dallying along for three or four days, that he could make up the difference on the last day and come out ahead.”

Another Chicago paper wrote, “Old Weston was beaten! The pampered and favored child of the Eastern metropolis was done for. We should like to know now what New York thinks of herself. Notwithstanding this gorgeous triumph, New Yorkers will still be welcomed at our hotels and will be fed at the same rates as other people.”

Another Chicago paper wrote, “Old Weston was beaten! The pampered and favored child of the Eastern metropolis was done for. We should like to know now what New York thinks of herself. Notwithstanding this gorgeous triumph, New Yorkers will still be welcomed at our hotels and will be fed at the same rates as other people.”

Also in Chicago, “Weston is used to defeat. His results have rarely, if ever, reached his expectations. Although he enjoys a national reputation as a ‘walkist’ and set out upon the present race with the assumption that an easy victory lay before him, was quite boastful and confident as to the result, he has been easily vanquished by a competitor who has hitherto had only a local reputation. O’Leary tramped and tramped steadily along, keeping to his work with steady persistence, while Weston joked, sung, chaffed with the spectators, and took delight in exhibiting himself.”

Six-Day Walks a Waste of Effort

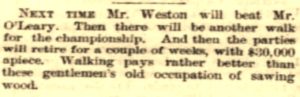

Still, many in Chicago thought the entire event was a waste of time. If the two wanted to race again, it was hoped that they would choose a different city. “We are entitled to have a rest. The most grateful thing that O’Leary and Weston can do is to walk off to St. Louis. The people there need amusement.”

Still, many in Chicago thought the entire event was a waste of time. If the two wanted to race again, it was hoped that they would choose a different city. “We are entitled to have a rest. The most grateful thing that O’Leary and Weston can do is to walk off to St. Louis. The people there need amusement.”

In Wisconsin: “We cannot regard the performance as otherwise than a show conceived and conducted for money-making purposes. As a test of muscle and endurance, the exhibition was perhaps one degree above a prize fight.”

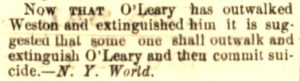

In Indiana: “The Washington Chronicle calls Weston and O’Leary a couple of idiots, which is a very mean kick at a defenseless class of the world’s population.” A strange one from New York: “Now that O’Leary has outwalked Weston and extinguished him, it is suggested that someone shall outwalk and extinguish O’Leary and then commit suicide.”

In Indiana: “The Washington Chronicle calls Weston and O’Leary a couple of idiots, which is a very mean kick at a defenseless class of the world’s population.” A strange one from New York: “Now that O’Leary has outwalked Weston and extinguished him, it is suggested that someone shall outwalk and extinguish O’Leary and then commit suicide.”

Anti-Westonism

The cruel comments about Weston again surfaced. In Mississippi: “There are two things that we are opposed to, skunks and Weston, the walkist. Chicago has just had a dose Of Weston. It would be a blessing to the community if Weston could only be induced to work in some steam mill, where there is a good prospect of an early explosion.”

The cruel comments about Weston again surfaced. In Mississippi: “There are two things that we are opposed to, skunks and Weston, the walkist. Chicago has just had a dose Of Weston. It would be a blessing to the community if Weston could only be induced to work in some steam mill, where there is a good prospect of an early explosion.”

In Chicago: “Weston would have beaten O’Leary if O’Leary hadn’t gone so far out of his way to beat him. Afterall, it is best that Weston didn’t spoil a glorious failure record by succeeding in what he undertook to do.”

O’Leary had proved that he was a worthy opponent for Weston and probably better. It was time to take this new popular sport internationally.

The parts of this Six-Day Race series:

- Part 1: (1773-1870) The Birth

- Part 2: (1870-1874) Edward Payson Weston

- Part 3: (1874) P.T. Barnum – Ultrarunning Promoter

- Part 4: (1875) First Six Day Race

- Part 5: (1875) Daniel O’Leary

- Part 6: (1875) Weston vs. O’Leary

- Part 7: (1876) Weston Invades England

- Part 8: (1876) First Women’s Six-Day Race

- Part 9: (1876) Women’s Six-day Frenzy

- Part 10: (1876) Grand Walking Tournament

- Part 11: (1877) O’Leary vs Weston II

- Part 12: (1878) First Astley Belt Race

- Part 13: (1878) Second Astley Belt Race

- Part 14: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 1

- Part 15: (1879) Third Astley Belt Race – Part 2

- Part 16: (1879) Women’s International Six-Day

Sources:

- P. S. Marshall, King of the Peds

- Tom Osler and Ed Dodd, Ultramarathoning: The Next Challenge

- Matthew Algeo, Pedestrianism: When Watching People Walk Was America’s Favorite Spectator Sport

- Interstate Exposition Building

- Gardner House

- The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), Oct 30, Nov 16, 18, 1875

- The Ottawa Free Trader (Illinois), Nov 6, 1875

- Chicago Tribune (Illinois), Nov 7, 12, 15-22, 1875

- The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), Nov 12, 15-22, 1875

- The Mobile Daily Tribune (Alabama), Nov 12, 1875

- The Leavenworth Times (Kansas), Nov 14, 1875

- Boston Post (Massachusetts), Nov 15, 1875

- The Philadelphia Times (Pennsylvania), Nov 25, 1875

- The Republican-Journal (Darlington, Wisconsin), Nov 26, 1875

- The Warrensburg Journal (Mississippi), Nov 26, 1875

- The Indianapolis News (Indiana), Nov 26, 1875

- The Fort Wayne Sentinel (Indiana), Nov 27, 1875

- The Clinton Public (Illinois), Dec 2, 1875

- The Semi-Weekly Advocate (Belleville, Illinois), Dec 3, 1875