Lens Use Prior to Fresnel by Thomas Tag (original) (raw)

Most lighthouse enthusiasts think that the Fresnel lens was the first lens used in lighthouses. However, that assumption is incorrect in that a number of lenses were proposed and put into use in the years before Augustin Fresnel designed his famous lens. This story will give you information about these early attempts to use lenses to augment the power of lighthouse optics.

The First Lens Proposals

One of the first known proposals for the use of a lens in a lighthouse occurred in the year 1759 when an optician from London proposed grinding the glass of the lantern windows at the Eddystone lighthouse to form lenses fifteen feet in diameter. The proposal was never accepted and would have been completely impractical because the center of these lenses would have been so thick that they would absorb most of the light within the glass.

Another early proposal came from William Hutchinson, the Dock Master at Liverpool, who suggested making lenses by blowing glass into moulds creating hollow lenses that were then to be filled with brine to prevent freezing. A lens of this type was actually created and tested. However, it failed because it broke due to the heat from the lamp and was too thick.

The First Lenses Put Into Actual Use

The inventor of the first lens put into use was Thomas Rogers. Mr. Rogers was born in London in the mid 1700s and became a glasscutter working in London. In 1786, Rogers was engaged in business with another optical expert, George Robinson of London. Together they were granted a patent for attaching glass ornamentation to furniture and mirrors. George Robinson also supplied lamps, reflectors, and later colored glass and small thick lenses to Trinity House the British Lighthouse Authority. (See more on the George Robinson Company below)

In 1787 Trinity House decided to review the operation of the French lighthouse authority. They found that the French appeared to be considerably advanced in the use of reflectors and the recently developed Argand lamp. Trinity House then constructed an experimental lighthouse at Blackheath where reflectors and lamps could be tested. Trinity House also invited proposals from individual inventors and manufacturers for improved lighting apparatus that could be used in lighthouses.

In August 1788 Thomas Rogers made a proposal to grind the panes of the lantern windows of a lighthouse lantern to form lenses. Trinity House accepted his proposal and began a trial at the Portland Bill Lighthouse in England of these new lenses. Rogers' lenses were 21 inches in diameter, and 5 ½ inches thick in the center. He also designed an Argand style lamp with a flame 3 inches in diameter. This was the first use of an Argand lamp in a lighthouse in England. Behind each lamp he placed a glass spherical reflector 18 inches in diameter that was formed of blown glass with a silver coating applied to the reverse side. These reflectors were also his design.

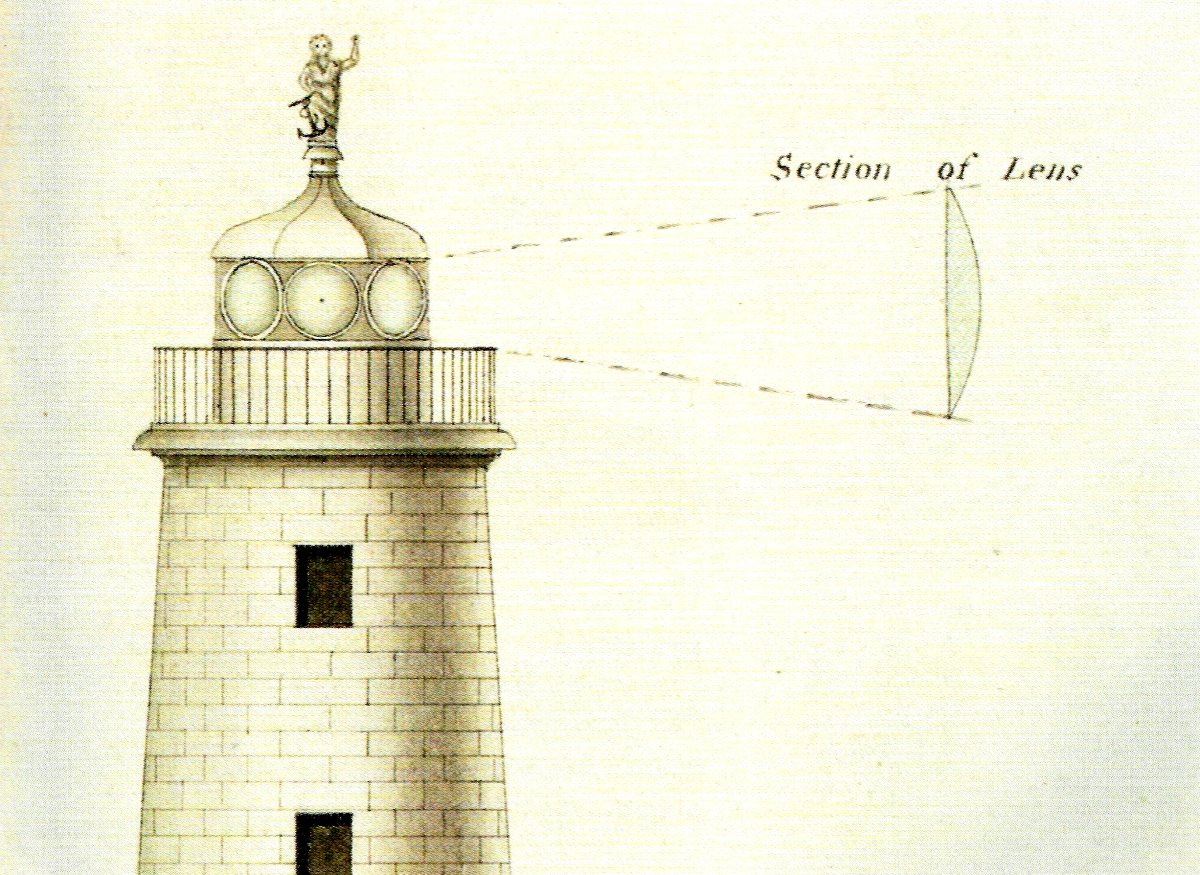

Drawing by Author - The Thomas Rogers Reflector, Lamp and Lens Design

Drawing by Robert Stevenson - The Portland Bill Lantern with Lenses in the Windows

In 1789, Rogers was invited by Admiral Sir Hugh Palliser to construct a new lighthouse at Howth Baily in Ireland. The original Howth Baily light used a coal-burning brazier on a square tower. Thomas Rogers replaced this design with a circular tower about 20-feet high topped by a 12-foot diameter lantern that had fixed oil lights using his lantern window lens design. In all there were 8 lamps using 12-inch reflectors and 8 lenses in the lantern windows. The new Howth Baily Lighthouse was completed in 1790.

Rogers' next lighthouse design was at North Foreland back in England where in 1792 he built a new addition to the tower and removed the coal brazier then in use. His design included a new lantern housing fifteen lamps and 18-inch diameter reflectors mounted in a circle providing a fixed light and using fifteen 18-inch diameter lenses again mounted in the lantern windows.

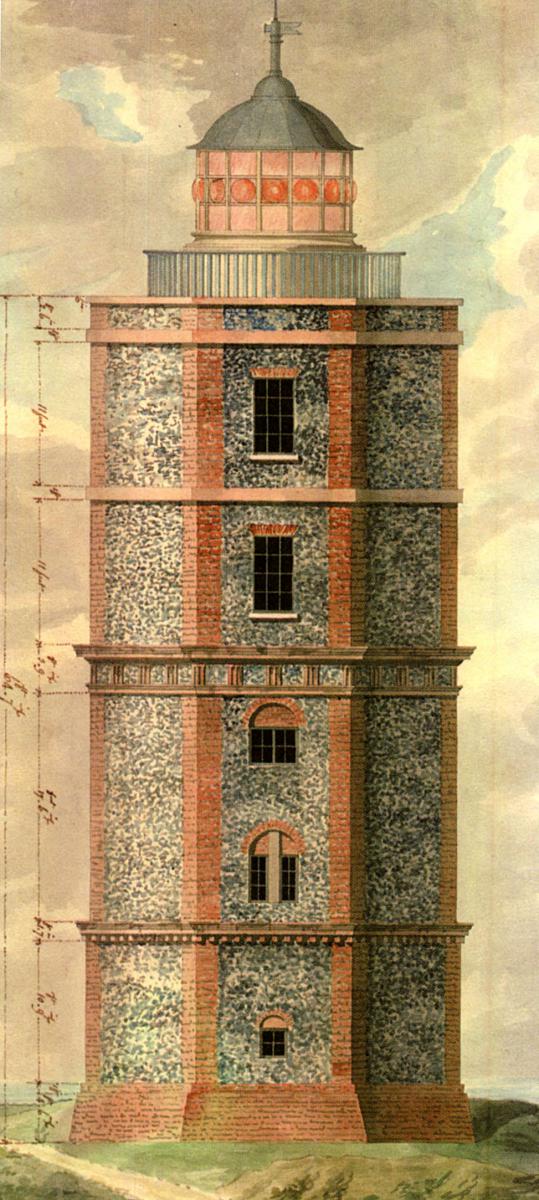

Drawing from Author's Collection - The North Foreland Lighthouse with Lenses in the Lantern Windows

In each of these designs Thomas Rogers used Argand style lamps that had 3-inch diameter wicks providing a large flame that was needed to provide enough light to the large lenses in the lantern windows. However, the glass used in the lenses was bottle green and had many bubbles and striae allowing little light to pass through. In all cases the lenses remained in use for only a few years.

Photo from Author's Collection - A Replica of what a Roger's Lamp may have looked like

In 1792 Rogers left the business with George Robinson and settled permanently in Ireland. Over the next twelve years Thomas Rogers made significant improvements to lighthouses around the Irish coast.

Thomas Rogers built new towers or lanterns and added lamps, reflectors and lenses at:

Howth Baily 1790 8 Lamps, 8, 12-inch Reflectors, 8 lenses, Fixed

Kilwarlin (South Rock) 1797 10 Lamps, 10, 15-inch Reflectors on revolving frame, Flashing

Aranmore 1798 unknown, Fixed

Cranfield Point 1802 12 Lamps, 12 Parabolic Reflectors, 12 22-inch lenses, Fixed

Loophead 1802 12 Lamps, 12 Parabolic Reflectors, 12 22-inch lenses, Fixed

He added lanterns, lamps, reflectors and sometimes lenses at:

Copeland Island 1796 6 Lamps, 6 Reflectors, Fixed

Old Head of Kinsale 1804 12 Lamps, 12 Reflectors, Fixed

Charles Fort 1804 3 Lamps, 3 Reflectors, Fixed

Duncannon Fort 1804 3 Lamps, 3 Reflectors, 3 Lenses, Fixed

Hook Head 1791 13 Lamps, 13 Reflectors, 10 lenses, 3 clear panes, Fixed

The Building of the Kilwarlin (South Rock) Lighthouse

One of Thomas Rogers' major achievements was the construction of the lighthouse at Kilwarlin (South Rock), a sea-swept rock off the coast of Ireland. On November 14, 1783 the Irish Parliament passed a resolution that a sum of £1,400 was to be granted to Lord Kilwarlin, Robert Ross, and George Hamilton towards erecting a lighthouse on the South Rock. Nothing happened for ten years until Thomas Rogers was invited by the Admiralty to build the lighthouse. Sadly, Lord Kilwarlin died during that year and never saw his namesake lighthouse. The light was first exhibited on 25 March 1797 and for the next eighty years it helped to provide a safe passage for mariners.

The Kilwarlin Lighthouse lies about three miles offshore. During the summer of 1794 a masonry platform 30 feet in diameter was prepared at Newcastle for the test assembly of the dressed granite stones. A short quay with loading sheers was also constructed for use as a harbor during the construction. The work then shut down for the winter. In March 1795 after resuming operations, the workmen found their previous work partially destroyed by the force of the sea during the winter, but by June the building of the tower began.

The Kilwarlin Lighthouse was a circular tower of granite with walls rising to a height of 60 feet. It was reinforced with vertical iron rods connecting to iron plates built into the walls as the building was erected. The tower was solid for the first 20 feet. The first floor entrance was at the 20 foot level with a door that faced southeast. Access was by an iron ladder secured to a narrow stone platform. The door was the only source of light at the entrance level which was used to store coal and water.

The second floor was used to store oil in cisterns, and the third floor held the kitchen with the living room at the fourth level. These top three rooms each had a small rectangular window. Holes 2-feet square were cut into the floors and ladders allowed passage between the levels.

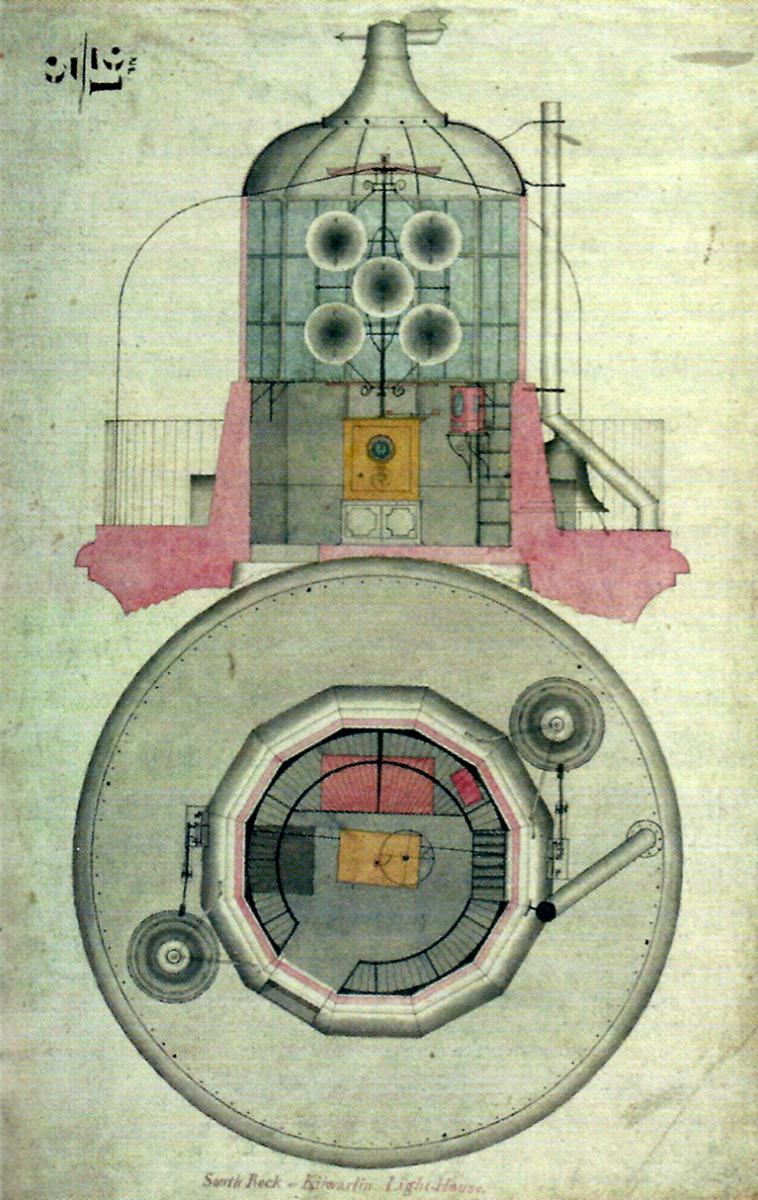

Above these rooms was a lantern 8-feet in diameter, with a lead covered cupola and weather vane. The light, which was first exhibited on 25 March 1797, consisted of a revolving frame with two sides with 5 reflectors on each of the sides giving a white flash. It total there were 10 Argand style lamps with 2-inch diameter wicks and 10-silvered reflectors each 15-inches in diameter. The frame was operated by a clockwork with a falling weight and the speed of its revolution was controlled by a governor. However, it was unreliable and reports stated that the keepers had, from time to time, to spend long stormy winter nights revolving the reflector frame by hand. This was the first revolving optic in an Irish lighthouse.

Drawing from Author's Collection - The Kilwarlin Lantern and Reflector Frame

The light gradually increased and decreased in strength, reaching its maximum intensity once in every 90 seconds. The light was 60 feet above the water and could be seen in clear weather at a distance of 12 miles. During foggy weather a bell was struck repeatedly.

In 1801 the sea began to undermine the foundations of the tower causing a considerable gap below it; this was remedied by filling the area with granite blocks held together with iron chains.

During the early 1800s Robert Stevenson visited the Kilwarlin Lighthouse to review its construction. He used the data gained in developing his design for the Bell Rock Lighthouse in Scotland then under construction.

Thomas Rogers Management of the Irish Lighthouses

When Thomas Rogers got his first contract for building the Kilwarlin Lighthouse the governing body for lighthouses in Ireland was the Irish Revenue Board. Rogers became the lighthouse engineer for the Revenue Board. However, he worked on a contract-by-contract basis. He was awarded contracts for building and for modernizing lighthouses and these contracts included provisions that he should supply all of the wicks, lamps, lamp chimneys, and other supplies needed for a period of ten years for each lighthouse he built or modernized. In addition, he was to select, train, and manage the keepers for all lighthouses under his contracts. Mr. Rogers became the engineer, supplier, manager, and inspector of the lighthouses he contracted for. This was a politically dangerous position for one man to have.

Thomas Rogers soon faced a number of critics. John Rennie an eminent civil engineer who later designed lighthouses himself visited the Kilwarlin Lighthouse in September 1805. He condemned the materials and design, and added that the building – “was constructed with but little judgment . . . unless some speedy and effectual steps are taken, I apprehend its duration will scarcely exceed the life of the architect . . .” Other complaints were received from time to time about the poor condition of some lighthouses and the poor training of some of the keepers.

Around 1810, the government began to get serious complaints about the inefficiency of the lighthouse service and Thomas Rogers’ management and inspection of the lighthouses. It was said that the lighthouses were poorly maintained and poorly managed. It was decided that the Dublin Ballast Board would be a more suitable body to manage Irish lighthouses than the Revenue Board. In 1810, by an Act of Parliament, the Ballast Board took over ten lighthouses and three harbor lights. Unknown to Rogers, the new authority lost no time in appointing three inspectors to visit and secretly report on the state of the lighthouses.

On September 26, 1810 George Halpin, Thomas Baker and William Baker inspected Kilwarlin Lighthouse and made their report – “The lantern of this building is well constructed and contains a revolving light of 10 lamps with glass cylinders and reflectors showing its full force once in a minute and a half, when wound up it continues in motion two hours. The lamps and apparatus were in clean good order, but the reflectors were bad, two frames of glass are broke, one badly and should be immediately replaced. There is to this light attached a bell to ring in foggy weather. The upper part of the building appears in good order, but we must observe that part of the platform or apron round the base has been blown up by the sea and requires to be made good with as little delay as possible to leave a plain surface around the building. The Lightkeeper appears to attend very particularly to his duty, the entire house being in the order we could wish.”

Their reports about the other lighthouses were much less satisfactory. Most of the lights were considered to be in passable condition, but many were found to be poorly maintained with broken lenses, and some had lanterns that leaked badly or had other structural defects. The Board began to take action and ordered Rogers to prepare estimates for the necessary repairs. Within a few months of receiving the confidential report, the Ballast Board set out to make further changes. The Board appointed George Halpin (Senior) as the new Engineer and Inspector of Lighthouses. Halpin worked directly for the Board, not on a contract-by-contract basis.

The Board then began to dispense with Rogers' services by gradually terminating his contracts for the management of various lighthouses. Rogers appealed to the Board that he was being unjustly treated. He also appealed to the Lord Lieutenant, but the Board was – “decidedly of the opinion that the business can best be conducted under their management and inspection with credit to themselves and advantage to the public” and the Lord Lieutenant did not step in to help.

Rogers received no compensation for the loss of his contracts. The Revenue Board had left everything to Thomas Rogers without any other regular system of inspection on their part. Rogers chose to manage the lighthouses himself, retaining more of the contract monies for himself. He also tended to appoint unskilled men as keepers Many were very old or partially incapacitated. He gave them little training, and he paid them poorly. Their average salary was just £15 per year at a time when the average salary was £30 per year or more.

Within two years much of the lighting apparatus installed by Rogers was being replaced by better equipment purchased mostly from his old company in London – George Robinson. In August 1812 a foreman of Robert Stevenson visited the Kilwarlin Lighthouse at the request of the new Irish Ballast Board and reported – “This machinery was first intended to make one revolution in one minute but at present it will not do so in two minutes, and the keeper is obliged to be almost continually at it, driving at one of the wheels which has a pin on it for that purpose. The ten reflectors in the lightroom had been carelessly made and because of the use of coarse cleaning materials little reflecting quality remained. The whole of the upper part of the reflectors is in one minute after they are lighted entirely black with smoke and the lightroom immediately filled. It would be useless to supply a new apparatus until the lighthouse is better kept, as to which the Superintendent could not direct the keeper.” At this point Thomas Rogers disappears from the records and his fate is unknown.

The George Robinson Company

George Robinson was an optics expert in London. Robinson began working with Thomas Rogers in 1786 and formed a lens, lantern and lamp company. Beginning in the 1790s, their company became the chief supplier of reflectors and lamps to Trinity House, the British Lighthouse Authority. Rogers left the company to work in Ireland in 1792 and George Robinson became sole proprietor. The Robinson Company eventually took in 13 year old Robert Wilkins as an apprentice and later as a partner and the company became known as G. Robinson & Wilkins. This company lasted into the early 1820s.

Beginning in the early 1800s George Robinson took on the additional responsibility of the Chief Inspector of lighthouses for Trinity House. Sometime after 1822 he sold the company to Robert Wilkins and the company became known as R. Wilkins & Co. Still later, Robert Wilkins added his son, William Crane Wilkins, as a partner and the company became R. Wilkins & Son. In 1846, that partnership was dissolved and the company became the property of William Crane Wilkins and was then known as “W. Wilkins Lighthouse Lantern and Lamp Manufacturer to Her Majesty.” The company was always located at Number 24 – 25 Long-Acre Street in east London.

The George Robinson Reflector, Lamp and Lens Designs

George Robinson built Trinity House's Flamborough Head Lighthouse, in 1806. The original oil-burning lighting apparatus was designed by George and consisted of a rotating vertical shaft to which were fixed 21 parabolic reflectors each 20 ½ inches in diameter, seven on each of the three sides of the frame. Red glass covered the reflectors on one side, which allowed for two white flashes followed by one red flash. This was the first use of red glass and the red characteristic in a lighthouse. Soon after Flamborough was completed Robert Stevenson visited the light and decided to use the red characteristic at the new Bell Rock Lighthouse then being built.

George Robinson went on to supply the reflectors and lamps for a number of British lighthouses notably: St. Agnes, Longships, the Lizard, Hurst Castle, Dungeness, Orfordness, Tynemouth, St. Ann’s, the Smalls and the South Stack. His equipment was also used in the first Australian lighthouse at Macquarie and at the Heligoland Lighthouse in Germany that was owned at that time by the British.

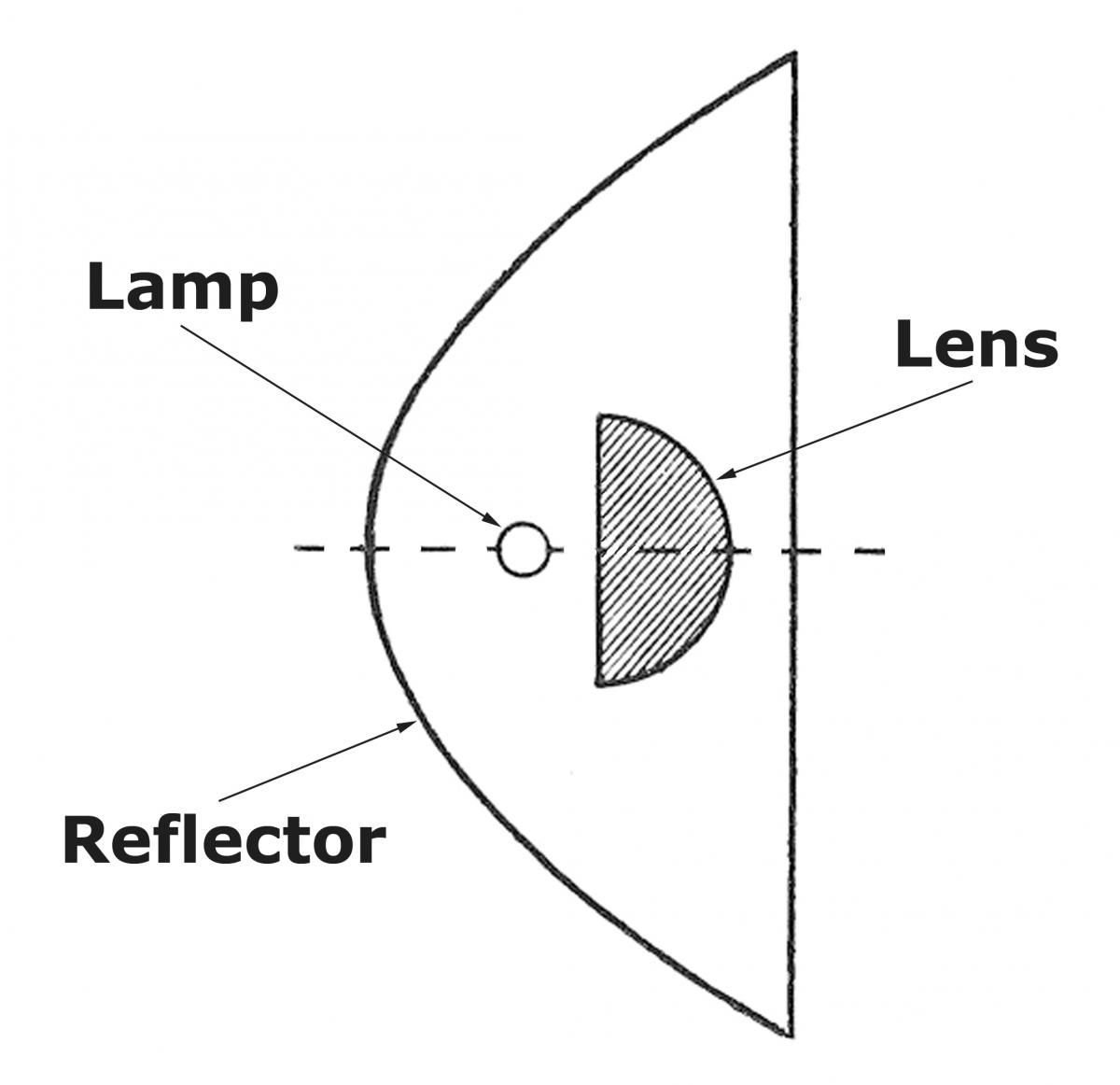

Robinson also designed small half-sphere lenses 4 ½ inches in diameter, 2 ¼ inches thick and set 2 1/8 inches from the focus of a parabolic reflector. These lenses were used in only two lighthouses – Flamborough Head in 1806 and the South Stack in 1809. These lenses at the South Stack were seen by Winslow Lewis in 1810 and became the basis for his reflector-lens design that was used in America. For more information about Winslow Lewis and his lamp and lens design see: The Keeper’s Log Volume 15, Number 1, pp. 16-27.

Drawing by Author - George Robinson's Reflector-Lens Combination

George Robinson’s lens design was very poor. The lens was of a half-spherical design that added no magnifying power to the light and each lens was made from green bottle glass with many bubbles and striae that interfered with the light. The reflectors were actually more powerful without the lens in place and the lenses were soon removed.

The British Parliament had some concern that George Robinson was both its lighthouse optics supplier and, at the same time, the Chief Inspector of lighthouses for Trinity House. Soon after these questions were raised in 1822, Robinson sold his business. He remained the Chief Inspector of lighthouses for Trinity House for a few more years and then retired into obscurity.

Now you have seen the first lighthouses lenses and know where they were and who made them. None of the first three lens makers was successful for long and only the Fresnel lens became an efficient lighthouse optic.