Lovable and Not-So-Lovable Rogues (original) (raw)

I’ve now read a few of the Best of the Baum Bugle volumes I just recently purchased, and there are some interesting articles in there, including some on the Nome King and L. Frank Baum’s other villains. I’ve already covered Ruggedo in a few posts, including Judy Pike’s point that he’s a somewhat sympathetic villain, as well as having a comic side to him. C. Warren Hollister’s “Baum’s Other Villains” makes a similar point about some of his other nasty characters, how they’re made figures of fun and given back stories that let you pity them somewhat, the suggestion being that evil thoughts and behavior are often the result of environment. They also frequently reform when faced with the chance to start over. Hollister describes the arguments of the invaders in The Emerald City of Oz, Gwig‘s weak attempts to justify his inaccurate predictions, the slapstick to which the Boolooroo is subjected, and Ann Soforth‘s exaggerated and pathetic imperialism. He also notes the ridiculously sadistic humor seen with the Growleywog jailor sticking pins into Guph and pulling out his whiskers. The silly names Baum tends to use are also noted, the Grand Gallipoot of the Growleywogs being the prime example, although maybe that actually sounds threatening in their culture; a lot of what language sounds funny is relative.

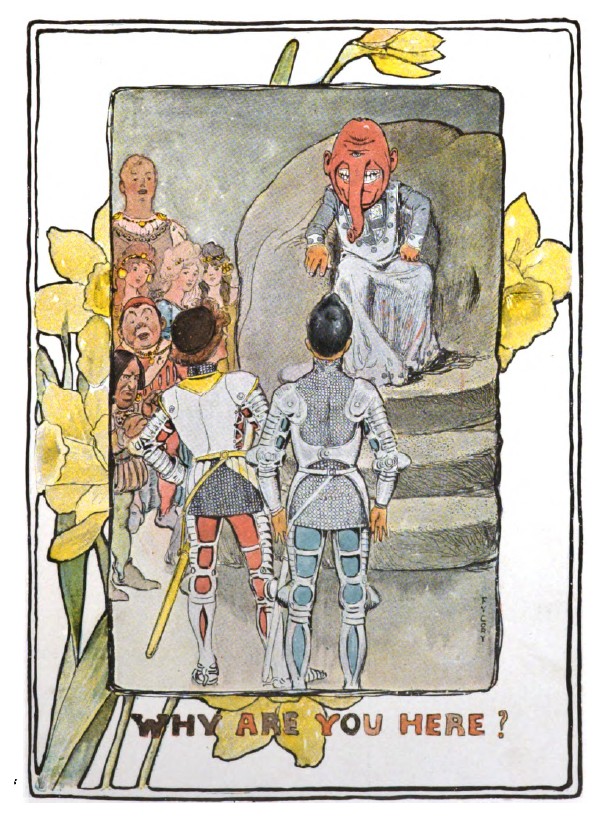

Still, it counts as Baum poking fun at his evildoers, even if other characters don’t see the humor as the Wizard of Oz does with Gwig. Ugu the Shoemaker is described as not knowing he’s wicked, and having been abandoned by his father and made to do a job he doesn’t like. Kiki Aru is sullen and bored, and turns to evil largely because he thinks it seems interesting. Zog and King Terribus of Spor are both driven to villainy by embarrassment over their hideous forms, and the latter reforms when Prince Marvel makes him handsome.

We don’t really know enough of Zog‘s back story to determine whether his ugliness ever actually caused problems for him, or it was entirely his own decision that a monstrous form meant he had to act like a monster. Eric Shanower does an interesting twist on this idea with Bortag in Enchanted Apples, who is mocked for not being ugly enough and turns to villainous magic, although he’s not very good at it. The Red Rogue of Dawna has a similar story as well, making himself a giant because he’s ashamed of how small he is. Zog is eventually killed, but many other villains give up their wicked ways. In some cases, this is done by removing their memories with the Water of Oblivion, letting them essentially start from scratch.

It’s hinted with the Nome King that this might not be foolproof, however, as he relearns his nasty ways. He reforms in Tik-Tok, then is a bad guy again in Magic. This book ends with his losing his memory once more and being given a home in Oz. Baum might have intended this to be permanent, but Ruth Plumly Thompson had him regaining his memory and wickedness in her books.

Whether the post-Baum authors retain the same take on their villains is an interesting question. Thompson does do something of the sort with King Skamperoo, the greedy and childish King of Skampavia in Wishing Horse.

He uses magic to conquer Oz, but with help from the Ozites and his horse Chalk, he becomes much kinder.

While he’s defeated, he’s able to negotiate a way to improve his own kingdom when he leaves. Often, however, Thompson seems to be rather more vindictive toward her villains, having many of them transformed. This happened to Ugu in Lost Princess as well, but there we found out that he preferred the form of a dove, and no longer had the desire to to be wicked. Abrog in Grampa, Captain Salt’s old crew in Pirates, Faleero in Purple Prince, and Bustabo in Ozoplaning are all turned into animals; but we never find out what they think of these forms, or whether they decide to reform or continue their villainy. It’s not like they’d be totally harmless in these forms, after all.

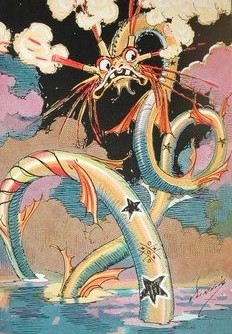

Quiberon, who’s monstrous and disagreeable but also seems to desire companionship, is petrified.

So is the naive but unfeeling Crunch in Cowardly Lion, who is determined to have wasted his life. Ruggedo, Mooj, Wutz, and Gludwig are also left in inanimate forms, and while they can presumably be brought back, there isn’t any indication that anyone wants to do so. Baum’s “Ozma and the Little Wizard” ends with the Wizard turning the three trouble-making Imps into buttons, but with the stipulation that they’d change form upon reforming.

But wouldn’t they presumably be unconscious, and hence not able make decisions, while in those forms? Then again, some inanimate objects in the series do seem to be at least somewhat conscious. It’s worth noting that, while Ozma reveals in Handy Mandy that the old Nome King’s jug transformation could be broken when dropped by the seventh hand of a traveling Mernite, she doesn’t actually know what a Mernite is at the time, and hence couldn’t break the enchantment herself without some research. So it’s really not that much different from having them destroyed, which she does with Mombi and Glegg. She doesn’t know the Triple Trick Tea will make Glegg explode, but nobody seems too broken up about it when it happens.

J.L. Bell has noted that Thompson shows a particular hatred for non-royals to try to force royalty to marry them, as happens with Glegg and Abrog. Mustafa, the Sultan of Samandra, and Strut of the Strat, who are already royalty, are barely punished at all. This doesn’t appear to be the case for Faleero or Ruggedo, both of whom were apparently legitimate rulers in their own right, although in the latter case he had previously been deposed by a higher authority. So the punishments don’t always fit the crime, but it does seem like some of them are serious enough threats that attempting to reform them could prove dangerous. Thompson’s villains tend to follow Baum’s in having jokey names and often comical personalities, but it’s less common for us to get into their backgrounds, which means less occasion for sympathy. Loxo the Lucky in Speedy is one Thompsonian antagonist whose point of view we do see, and while his shrinking down to normal human size is intended as a punishment, he doesn’t seem to mind it too much.

Beyond Thompson, it’s a little difficult to generalize about the treatment of villains. John R. Neill never really introduced any particular major threats, although it’s worth noting that the Bell-Snickle becomes a productive member of society and the painting of Mombi is repainted to be happy. Jack Snow’s Mimics were thoroughly evil to the end, and Conjo mostly just sought glory but was unhinged enough to be seriously dangerous. Terp the Terrible is never developed much beyond being a bully who turned himself into a giant. We do get into Singra’s head, but we don’t see that much beyond a desire for revenge and a rather sloppy mind. Sir Greves in Merry Go Round, not really a villain but unwittingly assisting one, is definitely treated sympathetically, his allowing Roundelay into the castle being due to his desire to pursue a path in life different from the one everyone expected of him. The Wizard also suggests that Slyddwyn, who’s pretty thoroughly nasty throughout Rundelstone, could potentially be reformed. Both Conjo and Singra have their memories wiped, and these later authors aren’t as keen as Thompson on having their villains petrified or otherwise transformed.